Incarnation

Incarnation literally means embodied in flesh or taking on flesh. It is the

Abrahamic religions

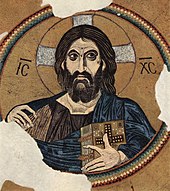

Christianity

The incarnation of

Islam

Islam completely rejects the doctrine of the incarnation (Mu'jassimā[4] / (Tajseem) Tajsīm) of God in any form, as the concept is defined as shirk. In Islam, God is one and "neither begets nor is begotten".[5]

Judaism

According to many modern scholars, the

Since the time of Maimonides, mainstream Judaism has mostly rejected any possibility of an incarnation of God in any form.[8]

However, some modern-day

Druze faith

Baháʼí Faith

In the Baháʼí Faith, God is not seen to be incarnated into this world and is not seen to be part of creation as he cannot be divided and does not descend to the condition of his creatures.[19] The Manifestations of God are also not seen as incarnations of God but are instead understood to be like perfect mirrors reflecting the attributes of God onto the material world.[20][21]

Buddhism

Buddhism is a nontheistic religion: it denies the concept of a creator deity or any incarnation of a creator deity. However, Buddhism does teach the rebirth doctrine and asserts that living beings are reborn, endlessly, reincarnating as devas (gods), demi-gods, human beings, animals, hungry ghosts or hellish beings,[22] in a cycle of samsara that stops only for those who reach nirvana (nibbana).[23][24][25]

In Tibetan Buddhism, an enlightened spiritual teacher (lama) is believed to reincarnate, and is called a tulku. According to Tulku Thond, there are three main types of tulkus. They are the emanations of buddhas, the manifestations of highly accomplished adepts, and rebirths of highly virtuous teachers or spiritual friends. There are also authentic secondary types, which include unrecognized tulkus, blessed tulkus, and tulkus fallen from the path.[26]

Hinduism

In

Neither the

The term is most commonly found in the context of the Hindu god

While avatars of other deities such as Ganesha and Shiva are also mentioned in medieval Hindu texts, this is minor and occasional.[37] The incarnation doctrine is one of the important differences between Vaishnavism and Shaivism traditions of Hinduism.[38][39]

Avatar versus incarnation

The translation of avatar as "incarnation" has been questioned by Christian theologians, who state that an incarnation is in flesh and imperfect, while avatar is mythical and perfect.[40][41] The theological concept of Christ as an Incarnation into the womb of the Virgin Mary and by work of the Holy Spirit God, as found in Christology, presents the Christian concept of incarnation. This, state Oduyoye and Vroom, is different from the Hindu concept of avatar because avatars in Hinduism are unreal and is similar to Docetism.[42] Sheth disagrees and states that this claim is an incorrect understanding of the Hindu concept of avatar.[43][note 1] Avatars are true embodiments of spiritual perfection, one driven by noble goals, in Hindu traditions such as Vaishnavism.[43]

Serer religion

The

See also

Notes

References

- ^ a b "Definition of Incarnation". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2022-05-28.

- ^ "Cambridge Dictionary: Incarnation". Cambridge Dictionary. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Incarnation". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Muhammad Abu Zahra, İslâm’da Siyâsî ve İ’tikadî Mezhepler Tarihi, History of Madhhabs in Islam, pp: 257 - 259, Fığlalı, Ethem Ruhi and Osman Eskicioğlu translation to Turkish, Yağmur, İstanbul, 1970.

- ^ Quran, (112:1-4).

- ^ Brand, Ezra. "Some Notes on the Anthropomorphization of God in the Talmud".

- ^ Brand, Ezra. ""He appeared to him as a [X]": Talmudic Stories of Incarnations of God, Eliyahu, Satan, and Demons". www.ezrabrand.com/. Retrieved 10 January 2024.

- ^ L. Jacobs 1973 A Jewish Theology p. 24. N.Y.: Berman House

- ^ Likkutei Sichos, Vol. 2, pp. 510-511.

- ISBN 978-1440841385.

- ^ a b Willi Frischauer (1970). The Aga Khans. Bodley Head. p. ?. (Which page?)

- ^ JSTOR 605981.

- ^ Minorities in the Middle East: A History of Struggle and Self-expression - Page 95 by Mordechai Nisan

- ^ The Druze in the Middle East: Their Faith, Leadership, Identity and Status - Page 41 by Nissim Dana

- ^ Encyclopaedic Survey of Islamic Culture - Page 94 by Mohamed Taher

- S2CID 201807131.

- ISBN 9780691134840.

- ISBN 9780030525964.

- ISBN 0-87743-190-6.

- ^ Cole, Juan (1982). "The Concept of Manifestation in the Baháʼí Writings". Études Baháʼí Studies. monograph 9. Ottawa: Canadian Association for Studies on the Baháʼí Faith: 1–38. Retrieved 2020-10-11 – via Bahá'í Library Online.

- ISBN 0-87743-264-3.

- ISBN 978-0-19-517398-7

- ISBN 978-0-521-85942-4.

- ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8.

- ISBN 978-0-415-18715-2.

- ^ Tulku Thondup (2011) Incarnation: The History and Mysticism of the Tulku Tradition of Tibet. Boston: Shambhala.

- ISBN 978-1-139-47206-7.

- ^ a b c Monier Monier-Williams (1923). A Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. p. 90.

- ^ Sheth 2002, p. 98.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-349-08642-9.

- ISBN 978-81-208-0170-7.

- ^ a b Paul Hacker 1978, pp. 415–417.

- ^ ISBN 0-8239-2287-1, pages 72-73

- ^ a b Sheth 2002, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Paul Hacker 1978, pp. 405–409.

- ^ Paul Hacker 1978, pp. 424, also 405-409, 414–417.

- ISBN 0-8239-2287-1, page 635

- ISBN 978-981-230-754-5.

- ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5.

- ^ Sheth 2002, pp. 107–109.

- ISBN 978-0-7007-1281-6.

- ISBN 978-90-420-0897-7, p. 111.

- ^ a b Sheth 2002, p. 108.

- ^ Sheth 2002, p. 99.

- ^ ISBN 2-7236-0868-9

- ^ (in French) Thaiw, Issa Laye, « La religiosité des Seereer, avant et pendant leur islamisation », in Éthiopiques, no. 54, volume 7, 2e semestre 1991 [1] Archived 2019-09-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 2-7236-0877-8

Bibliography

- ISBN 0-89281-354-7. pp. 164–187.

- Coleman, T. (2011). "Avatāra". Oxford Bibliographies Online: Hinduism. doi:10.1093/obo/9780195399318-0009. Short introduction and bibliography of sources about Avatāra (subscription required).)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link - Matchett, Freda (2001). Krishna, Lord or Avatara?: the relationship between Krishna and Vishnu. Routledge. ISBN 978-0700712816.

- Paul Hacker (1978). Lambert Schmithausen (ed.). Zur Entwicklung der Avataralehre (in German). Otto Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3447048606.

- Sheth, Noel (2002). "Hindu Avatāra and Christian Incarnation: A Comparison". Philosophy East and West. 52 (1 (January)). S2CID 170278631.