List of Greek and Roman architectural records

This is the list of ancient architectural records consists of record-making architectural achievements of the Greco-Roman world from c. 800 BC to 600 AD.

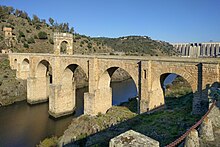

Bridges

- The highest bridge over the water or ground was the single-arched Pont d'Aël which carried irrigation water for Aosta across a deep Alpine gorge. The height of its deck over the torrent below measures 66 m.[1]

- The largest bridge by span was the Trajan's Bridge over the lower Danube. Its twenty-one timber arches spanned 50 m each from centreline to centreline.[2]

- The largest pointed arch bridge by span was the Karamagara Bridge in Cappadocia with a clear span of 17 m. Constructed in the 5th or 6th century AD across a tributary of the Euphrates, the now submerged structure is one of the earliest known examples of pointed architecture in late antiquity, and may even be the oldest surviving pointed arch bridge.[3]

- The largest rivers to be spanned by solid bridges were the the Roman feat appears to be unsurpassed anywhere in the world until well into the 19th century.

- The longest bridge, and one of the longest of all time, was Puente Romano at Mérida, Spain (today 790 m). The total length of all aqueduct arch bridges of the Aqua Marcia to Rome, constructed from 144 to 140 BC, amounts to 10 km.[8]

Bridge at Limyra

, Turkey- The longest segmental arch bridge was the c. 1,100 m long Bridge at Limyrain modern-day Turkey, consisting of twenty-six flat brick arches, features the greatest lengths of all extant masonry structures in this category (360 m).

- The tallest bridge was the bridge at Narni, Italy, which rose above the stream-level c. 42 m and 30 m, respectively.[9]

- The widest bridge was the Pergamon Bridge in Pergamon, Turkey. The structure served as a substruction for a large court in front of the Serapis Temple, allowing the waters of the Selinus river to pass unrestricted underneath. Measuring 193 m in width, the dimensions of the extant bridge are such that it is frequently mistaken for a tunnel, although the whole structure was actually erected above ground. A similar design was also executed in the Nysa Bridge which straddled the local stream on a length of 100 m, supporting a forecourt of the city theatre.[10] By comparison, the width of a normal, free standing Roman bridge did not exceed 10 m.[11]

- The bridge with the greatest load capacity – as far as can be determined from the limited research – was the live loads imposed by ancient traffic.[12]

Ratio of clear span against rise, arch rib and pier thickness:

- The bridge with the flattest arches was the Bridge at Limyra, the Ponte San Lorenzo and the Alconétar Bridge.[14] By comparison, the Florentine Ponte Vecchio, one of the earliest segmental arch bridges in the Middle Ages, features a ratio of 5.3 to 1.

- The bridge with the most slender arch was the Pont-Saint-Martin in the Alpine Aosta Valley.[15] A favourable ratio of arch rib thickness to span is regarded as the single most important parameter in the design of stone arches.[16] The arch rib of the Pont-Saint-Martin is only 1.03 m thick what translates to a ratio of 1/34 respectively 1/30 depending on whether one assumes 35.64 m[15] or 31.4 m[17] to be the value for its clear span. A statistical analysis of extant Roman bridges shows that ancient bridge builders preferred a ratio for rib thickness to span of 1/10 for smaller bridges, while they reduced this to as low as 1/20 for larger spans in order to relieve the arch from its own weight.[18]

- The bridge with the most slender piers was the three-span Ponte San Lorenzo in Padua, Italy. A favourable ratio between pier thickness and span is considered a particularly important parameter in bridge building, since wide openings reduce stream velocities which tend to undermine the foundations and cause collapse.[19] The approximately 1.70 m thick piers of the Ponte San Lorenzo are as slender as one-eighth of the span.[20] In some Roman bridges, the ratio still reached one-fifth, but a common pier thickness was around one third of the span.[21] Having been completed sometime between 47 and 30 BC, the San Lorenzo Bridge also represents one of the earliest segmental arch bridges in the world with a span to rise ratio of 3.7 to 1.[14]

Canals

- The largest canal appears to be the Babylon.[23] A particularly ambitious canal scheme which never came to fruition was Nero's Corinth Canal project, work on which was abandoned after his murder.[24]

Columns

- Note: This section makes no distinction between columns composed of drums and monolithic shafts; for records concerning solely the latter, see monoliths.

Pompey's Pillar

, the highest free-standing monolithic ancient Corinthian column (26.85 m)

- The tallest victory column in Column of Theodosius, which no longer exists, with the height of its top above ground being c. 50 m.[25] The Column of Arcadius, whose 10.5 m base alone survives, was c. 46.1 m high.[26] The Column of Constantine may originally have been as high as 40 m above the pavement of the Forum.[27] The height of the Column of Justinianis unclear, but it may have been even larger. The height of each of these monuments was originally even higher, as all were further crowned with a colossal imperial statue several times life-size.

- The tallest victory column in Rome was the Column of Marcus Aurelius, Rome, with the height of its top above ground being c. 39.72 m. It thus exceeds its earlier model, Trajan's Column, by 4.65 m, chiefly due to its higher pedestal.[28]

- The tallest monolithic column was Pompey's Pillar in Alexandria which is 26.85 m high with its base and capital and whose monolithic column shaft measures 20.75 m.[29][30] The statue of Diocletian atop "Pompey's" Pillar was itself approximately 7 m tall.[31]

- The tallest Olympieion which are 17.74 m (14.76 m) respectively 16.83 m (14 m) high. These are followed by a group of three virtually identical high Corinthian orders in Rome: the Hadrianeum, the Temple of Apollo Sosianus and the Temple of Castor and Pollux, all of which are in the order of 14.8 m (12.4 m) height.[32]

Dams

- The largest arch dam was the Glanum Dam in the French Provence. Since its remains were nearly obliterated by a 19th-century dam on the same spot, its reconstruction relies on prior documentation, according to which the Roman dam was 12 m high, 3.9 m wide and 18 m long at the crest.[33] Being the earliest known arch dam,[34] it remained unique in antiquity and beyond (aside from the Dara Dam whose dimensions are unknown).[35]

- The largest List of Roman dams).

- The largest bridge dam was the Sassanid territory in the 3rd century AD.[38] The approximately 500 m long structure, a novel combination of overflow dam and arcaded bridge,[39] crossed Iran's most effluent river on more than forty arches.[40] The most eastern Roman civil engineering structure ever built,[41] its dual-purpose design exerted a profound influence on Iranian dam building.[42]

- The largest multiple arch buttress dam was the Esparragalejo Dam in Spain, whose 320 m long wall was supported on its air face alternatingly by buttresses and concave-shaped arches.[43] Dated to the 1st century AD, the structure represents the first and, as it appears, only known dam of its type in ancient times.[44]

- The longest buttress dam was the 632+ m long Consuegra Dam (3rd–4th century AD) in central Spain which is still fairly well preserved.[45] Instead of an earth embankment, its only 1.3 m thick retaining wall was supported on the downstream side by buttresses in regular intervals of 5 to 10 m.[43] In Spain, a large number of ancient buttress dams are concentrated, representing nearly one-third of the total found there.[46]

- The longest gravity dam, and longest dam overall, impounds Lake Homs in Syria. Built in 284 AD by emperor Diocletian for irrigation, the 2,000 m long and 7 m high masonry dam consists of a concrete core protected by basalt ashlar.[47] The lake, 6 miles long by 2.5 miles wide,[48] had a capacity of 90 million m3, making it the biggest Roman reservoir in the Near East[49] and possibly the largest artificial lake constructed up to that time.[48] Enlarged in the 1930s, it is still a landmark of Homs which it continues to supply with water.[50] Further notable dams in this category include the little-studied 900 m long Wadi Caam II dam at Leptis Magna[51] and the Spanish dams at Alcantarilla and at Consuegra.

- The tallest dam belonged to the town of the same name.[52] Constructed by Nero (54–68 AD) as an adjunct to his villa on the Aniene river, the three reservoirs were highly unusual in their time for serving recreational rather than utilitarian purposes.[53] The biggest dam of the group is estimated to have reached a height of 50 m.[54] It remained unsurpassed in the world until its accidental destruction in 1305 by two monks who fatally removed cover stones from the top.[55] Also quite tall structures were Almonacid de la Cuba Dam (34 m), Cornalvo Dam (28 m) and Proserpina Dam(21.6 m), all of which are located in Spain and still of substantially Roman fabric.

Domes

- The largest dome in the world for more than 1,700 years was the

- The largest dome out of clay hollowware ever constructed is the caldarium of the Baths of Caracalla in Rome. The now ruined dome, completed in 216 AD, had an inner diameter of 35.08 m.[60] For reduction of weight its shell was constructed of amphora joined together, a quite new method then which could do without time-consuming wooden centring.[61]

- The largest half-domes were found in the Baths of Trajan in Rome, completed in 109 AD. Several exedrae integrated into the enclosure wall of the compound reached spans up to 30 m.[57]

- The largest stone dome was the Western Thermae in

Fortifications

Peiraeus

(5th c. BC)- The longest city walls were those of Peiraeus port. A corridor between these two was established by the northern Long Wall (40 stades or 7.1 km) and the Phaleric Wall (35 stades or 6.2 km). Assuming a value of 177.6 m for one Attic stade,[65] the overall length of the walls of Athens thus measured about 31.6 km. The structure, consisting of sun-dried bricks built on a foundation of limestone blocks, was dismantled after Athens' defeat in 404 BC, but rebuilt a decade later.[66] Syracuse, Rome (Aurelian Walls) and Constantinople (Walls of Constantinople) were also protected by very long circuit walls.

Monoliths

Stone of the Pregnant Woman

, the second largest monolith quarried, weighs c. 1,000 t- The largest monolith lifted by a single crane can be determined from the characteristic lewis iron holes (each of which points at the use of one crane) in the lifted stone block. By dividing its weight by their number, one arrives at a maximum lifting capacity of 7.5 to 8 t as exemplified by a cornice block at the Trajan's Forum and the architrave blocks of the Temple of Jupiter at Baalbek.[67] Based on a detailed Roman relief of a construction crane, the engineer O'Connor calculates a slightly less lifting capability, 6.2 t, for such a type of treadwheel crane, on the assumption that it was powered by five men and using a three-pulley block.[68]

- The largest monolith lifted by cranes was the 108 t heavy corner cornice block of the Jupiter temple at Baalbek, followed by an architrave block weighing 63 t, both of which were raised to a height of about 19 m.[69] The capital block of Trajan's Column, with a weight of 53.3 t, was even lifted to c. 34 m above the ground.[70] As such enormous loads far exceeded the lifting capability of any single treadwheel crane, it is assumed that Roman engineers set up a four-masted lifting tower in the midst of which the stone blocks were vertically raised by the means of capstans placed on the ground around it.[71]

- The largest monoliths hewn were two giant building blocks in the quarry of Baalbek: an

- The largest monolith moved was the the largest man-made monoliths in history.

- The largest Pompey's Pillar, a free-standing victory column erected in Alexandria in 297 AD: measuring 20.46 m high with a diameter of 2.71 m at its base, the weight of its granite shaft has been put at 285 t.[29]

- The largest monolithic dome crowned the early 6th century AD Ostrogothic kingdom. The weight of the single, 10.76 m wide roof slab has been calculated at 230 t.[81]

Obelisks

- The tallest obelisks are all located in Rome, adorning its inner-city squares. The Agonalis obelisk on

Roads

- The longest trackway was the gauge of around 160 cm between two parallel grooves cut into the limestone paving,[84] it remained in regular and frequent service for at least 650 years.[85] By comparison, the world's first overland wagonway, the Wollaton Wagonwayof 1604, ran for c. 3 km.

Roofs

- The largest post and lintel roof by span spanned the Parthenon in Athens. It measured 19.20 m between the cella walls, with an unsupported span of 11.05 m between the interior colonnades.[86] Sicilian temples of the time featured slightly larger cross sections, but these may have been covered by truss roofs instead.[87]

- The largest truss roof by span covered the Aula Regia (throne room) built for emperor Domitian (81–96 AD) on the Palatine Hill, Rome. The timber truss roof had a width of 31.67 m, slightly surpassing the postulated limit of 30 m for Roman roof constructions. Tie-beam trusses allowed for much larger spans than the older prop-and-lintel system and even concrete vaulting: Nine out of the ten largest rectangular spaces in Roman architecture were bridged this way, the only exception being the groin vaulted Basilica of Maxentius.[88]

Tunnels

- The deepest tunnel was the Tunnels of Claudius, constructed in eleven years time by emperor Claudius (41–54 AD). Draining the Fucine Lake, the largest Italian inland water, 100 km east of Rome, it is widely deemed as the most ambitious Roman tunnel project as it stretched ancient technology to its limits.[89] The 5653 m long qanat tunnel, passing under Monte Salviano, features vertical shafts up to 122 m depth; even longer ones were run obliquely through the rock.[90] After repairs under Trajan and Hadrian, the Claudius tunnel remained in use until the end of antiquity. Various attempts at restoration succeeded only in the late 19th century.[91]

- The longest road tunnel was the Cocceius Tunnel near Naples, Italy, which connected Cumae with the base of the Roman fleet, Portus Julius. The 1000 m long tunnel was part of an extensive underground network which facilitated troop movements between the various Roman facilities in the volcanic area. Built by the architect Cocceius Auctus, it featured paved access roads and well-built mouthes. Other road tunnels include the Crypta Neapolitana to Pozzuoli (750 m long, 3–4 m wide and 3–5 m high), and the similarly sized Grotta di Seiano.[92]

- The longest Battle of Yarmuk in 636.[95]

- The longest tunnel excavated from opposite ends was built around the end of the 6th century BC for draining and regulating Lake Nemi, Italy.[96] Measuring 1600 m, it was almost 600 m longer than the slightly older Tunnel of Eupalinos on the isle of Samos, the first tunnel in history to be excavated from two ends with a methodical approach.[97] The Albano Tunnel, also in central Italy, reaches a length of 1,400 m.[98] It was excavated no later than 397 BC and is still in service. Determining the tunnelling direction underground and coordinating the advance of the separate work parties made meticulous surveying and execution on the part of the ancient engineers necessary.

Vaulting

- The largest barrel vault by span covered the Temple of Venus and Roma, Rome. Built between 307 and 312 AD, the vaulted structure replaced the original timber truss roof from Hadrian's time.[88]

- The largest Forum Romanum, built in the early 4th century AD.[88]

Miscellaneous

- The greatest concentration of mechanical power was the empire.[101]

- The longest spiral stair belonged to the 2nd century AD Trajan's Column in Rome. Measuring a height of 29.68 m, it surpassed its successor, the Column of Marcus Aurelius, by a mere 6 cm. Its treads were carved out ouf nineteen massive marble blocks so that each drum comprised a half-turn of seven steps. The quality of the craftsmanship was such that the staircase was practically even, and the joints between the huge blocks accurately fitting. The design of the Trajan's column had a profound influence on Roman construction technique, and the spiral stair became over time an establish architectural element.[102]

- The longest straight alignment was constituted by an 81.259 km long section of the groma, a surveying instrument which was used by the Romans to great effect in land division and road construction.[103]

See also

- Ancient Greek architecture

- Greek technology

- Ancient Roman architecture

- Roman technology

- Roman engineering

References

- ^ Döring 1998, pp. 131f. (fig. 10)

- ^ a b c d O'Connor 1993, pp. 142–145

- ^ Galliazzo 1995, pp. 92, 93 (fig. 39)

- ^ O'Connor 1993, pp. 133–139

- ^ Fernández Troyano 2003

- ^ Tudor 1974, p. 139; Galliazzo 1994, p. 319

- ^ O'Connor 1993, p. 99

- ^ O'Connor 1993, p. 151

- ^ O'Connor 1993, p. 154f.

- ^ Grewe & Özis 1994, pp. 348–352

- ^ O'Connor 1993

- ^ a b Durán Fuentes 2004, pp. 236f.

- ^ Wurster & Ganzert 1978, p. 299

- ^ a b O'Connor 1993, p. 171

- ^ a b O'Connor 1993, p. 169 (fig. 140)–171

- ^ O'Connor 1993, p. 167

- ^ Frunzio, Monaco & Gesualdo 2001, p. 592

- ^ O'Connor 1993, pp. 168f.

- ^ O'Connor 1993, p. 165; Heinrich 1983, p. 38

- ^ O'Connor 1993, p. 92; Durán Fuentes 2004, pp. 234f.

- ^ O'Connor 1993, pp. 164f.; Durán Fuentes 2004, pp. 234f.

- ^ Schörner 2000, pp. 34f.

- ^ Schörner 2000, pp. 36f.

- ^ Werner 1997, pp. 115f

- ^ Gehn, Ulrich. "LSA-2458: Demolished spiral column once crowned by colossal statue of Theodosius I, emperor; later used for statue of Anastasius, emperor. Constantinople, Forum of Theodosius (Tauros). 386-394 and 506". Last Statues of Antiquity. Oxford University. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Gehn, Ulrich (2012). "LSA-2459: Demolished spiral column once crowned by colossal statue of Arcadius, emperor. Constantinople, Forum of Arcadius. 401-21". Last Statues of Antiquity. Oxford University. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- .

- ^ Jones 2000, p. 220

- ^ a b Adam 1977, pp. 50f.

- ^ Gehn, Ulrich (2012). "LSA-874: Column used as base for statue of Diocletian, emperor (so-called 'Column of Pompey'). Alexandria (Aegyptus). 297-302". Last Statues of Antiquity. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Bergmann, Marianne (2012). "LSA-1005: Fragments of colossal porphyry statue of Diocletian in cuirass (lost ). From Alexandria. 297-302". Last Statues of Antiquity. Oxford University. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Jones 2000, pp. 224f. (table 2)

- ^ Schnitter 1978, pp. 31f.

- ^ Smith 1971, pp. 33–35; Schnitter 1978, pp. 31f.; Schnitter 1987a, p. 12; Schnitter 1987c, p. 80; Hodge 2000, p. 332, fn. 2

- ^ Schnitter 1987b, p. 80

- ^ Dimensions: Smith 1971, pp. 35f.

- ^ Gravity dam: Smith 1971, pp. 35f.; Schnitter 1978, p. 30; arch-gravity dam: James & Chanson 2002

- ^ Smith 1971, pp. 56–61; Schnitter 1978, p. 32; Kleiss 1983, p. 106; Vogel 1987, p. 50; Hartung & Kuros 1987, p. 232; Hodge 1992, p. 85; O'Connor 1993, p. 130; Huff 2010; Kramers 2010

- ^ Vogel 1987, p. 50

- ^ Hartung & Kuros 1987, p. 246

- ^ Schnitter 1978, p. 28, fig. 7

- ^ Huff 2010; Smith 1971, pp. 60f.

- ^ a b Schnitter 1978, p. 29

- ^ Schnitter 1978, p. 29; Schnitter 1987b, pp. 60, table 1, 62; James & Chanson 2002; Arenillas & Castillo 2003

- ^ Schnitter 1978, p. 29; Arenillas & Castillo 2003

- ^ Arenillas & Castillo 2003

- ^ Smith 1971, pp. 39–42; Schnitter 1978, p. 31; Hodge 1992, p. 91

- ^ a b Smith 1971, p. 42

- ^ Hodge 1992, p. 91; Hodge 2000, p. 338

- ^ Hodge 1992, p. 91

- ^ Smith 1971, p. 37

- ^ Smith 1970, pp. 60f.; Smith 1971, p. 26; Schnitter 1978, p. 28

- ^ Smith 1970, pp. 60f.; Smith 1971, p. 26

- ^ Hodge 1992, p. 82 (table 39)

- ^ Smith 1970, pp. 65 & 68; Hodge 1992, p. 87

- ^ Mark & Hutchinson 1986, p. 24

- ^ a b Rasch 1985, p. 119

- ^ Romanconcrete.com

- ^ Mark & Hutchinson 1986, p. 24; Müller 2005, p. 253

- ^ Heinle & Schlaich 1996, p. 27

- ^ Rasch 1985, p. 124

- ^ Rasch 1985, p. 126

- ^ Thucydides, "A History of the Peloponnesian War", 2.13.7

- ^ Scranton 1938, p. 529

- Livius.org: Money, Weights and Measures in Antiquity

- Livius.org: Long Walls

- ^ Lancaster 1999, p. 436

- ^ O'Connor 1993, pp. 49f.; Lancaster 1999, p. 426

- ^ Coulton 1974, pp. 16, 19

- ^ Lancaster 1999, p. 426

- ^ Lancaster 1999, pp. 426−432

- ^ Ruprechtsberger 1999, p. 17

- ^ Ruprechtsberger 1999, p. 15

- ^ Ruprechtsberger 1999, pp. 18–20

- ^ a b Adam 1977, p. 52

- ^ Adam 1977, pp. 52–63

- ^ a b Lancaster 2008, pp. 258f.

- ^ Davies, Hemsoll & Jones 1987, pp. 150f., fn. 47

- ^ Scaife 1953, p. 37

- ^ Maxfield 2001, p. 158

- ^ Heidenreich & Johannes 1971, p. 63

- ^ Habachi & Vogel 2000, pp. 103–113

- ^ Raepsaet & Tolley 1993, p. 246; Lewis 2001b, p. 10; Werner 1997, p. 109

- ^ Lewis 2001b, pp. 10, 12

- ^ Verdelis 1957, p. 526; Cook 1979, p. 152; Drijvers 1992, p. 75; Raepsaet & Tolley 1993, p. 256; Lewis 2001b, p. 11

- ^ Hodge 1960, p. 39

- ^ Klein 1998, p. 338

- ^ a b c Ulrich 2007, p. 148f.

- ^ Grewe 1998, p. 97

- ^ Grewe 1998, p. 96

- ^ Grewe 1998, p. 92

- ^ Grewe 1998, pp. 124–127

- ^ Döring 2007, p. 25

- ^ Döring 2007, p. 27

- ^ Döring 2007, pp. 31–32

- ^ Grewe 1998, pp. 82–87

- ^ Burns 1971, p. 173; Apostol 2004, p. 33

- ^ Grewe 1998, pp. 87–89

- ^ Greene 2000, p. 39

- ^ Wilson 2002, pp. 11–12

- ^ Wilson 2001, pp. 231–236; Wilson 2002, pp. 12–14

- ^ Jones 1993, pp. 28–31; Beckmann 2002, pp. 353–356

- ^ Lewis 2001a, pp. 242, 245

Sources

- Adam, Jean-Pierre (1977), "À propos du trilithon de Baalbek: Le transport et la mise en oeuvre des mégalithes", Syria, 54 (1/2): 31–63,

- Apostol, Tom M. (2004), "The Tunnel of Samos" (PDF), Engineering and Science (1): 30–40, archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2011, retrieved 12 September 2012

- Arenillas, Miguel; Castillo, Juan C. (2003), "Dams from the Roman Era in Spain. Analysis of Design Forms (with Appendix)", 1st International Congress on Construction History [20th–24th January], Madrid

- Beckmann, Martin (2002), "The 'Columnae Coc(h)lides' of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius", Phoenix, 56 (3/4): 348–357, JSTOR 1192605

- Burns, Alfred (1971), "The Tunnel of Eupalinus and the Tunnel Problem of Hero of Alexandria", Isis, 62 (2): 172–185, S2CID 145064628

- Cook, R. M. (1979), "Archaic Greek Trade: Three Conjectures 1. The Diolkos", The Journal of Hellenic Studies, 99: 152–155, S2CID 161378605

- O'Connor, Colin (1993), Roman Bridges, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-39326-4

- Coulton, J. J. (1974), "Lifting in Early Greek Architecture", S2CID 162973494

- Döring, Mathias (2007), "Wasser für Gadara. 94 km langer antiker Tunnel im Norden Jordaniens entdeckt" (PDF), Querschnitt (21), Darmstadt University of Applied Sciences: 24–35, archived from the original (PDF) on 11 January 2016, retrieved 12 September 2012

- Drijvers, J.W. (1992), "Strabo VIII 2,1 (C335): Porthmeia and the Diolkos", Mnemosyne, 45: 75–78

- Döring, Mathias (1998), "Die römische Wasserleitung von Pondel (Aostatal)", Antike Welt, 29 (2): 127–134

- Durán Fuentes, Manuel (2004), La Construcción de Puentes Romanos en Hispania, Santiago de Compostela: Xunta de Galicia, ISBN 978-84-453-3937-4

- Fernández Troyano, Leonardo (2003), Bridge Engineering. A Global Perspective, London: Thomas Telford Publishing, ISBN 0-7277-3215-3

- Frunzio, G.; Monaco, M.; Gesualdo, A. (2001), "3D F.E.M. Analysis of a Roman Arch Bridge", in Lourenço, P.B.; Roca, P. (eds.), Historical Constructions (PDF), Guimarães: University of Minho, pp. 591–597, archived from the original (PDF) on 21 August 2007

- Galliazzo, Vittorio (1995), I ponti romani, vol. 1, Treviso: Edizioni Canova, ISBN 88-85066-66-6

- Galliazzo, Vittorio (1994), I ponti romani. Catalogo generale (in Italian), vol. 2, Treviso: Edizioni Canova, pp. 319f. (No. 645), ISBN 88-85066-66-6

- Greene, Kevin (2000), "Technological Innovation and Economic Progress in the Ancient World: M.I. Finley Re-Considered", The Economic History Review, New Series, 53 (1): 29–59,

- Grewe, Klaus; Özis, Ünal (1994), "Die antiken Flußüberbauungen von Pergamon und Nysa (Türkei)", Antike Welt, 25 (4): 348–352

- Grewe, Klaus (1998), Licht am Ende des Tunnels. Planung und Trassierung im antiken Tunnelbau, Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, ISBN 3-8053-2492-8

- Habachi, Labib; Vogel, Carola (2000), Die unsterblichen Obelisken Ägyptens, Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, ISBN 3-8053-2658-0

- Hartung, Fritz; Kuros, Gh. R. (1987), "Historische Talsperren im Iran", in Garbrecht, Günther (ed.), Historische Talsperren, vol. 1, Stuttgart: Verlag Konrad Wittwer, pp. 221–274, ISBN 3-87919-145-X

- Heidenreich, Robert; Johannes, Heinz (1971), Das Grabmal Theoderichs zu Ravenna, Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag

- Heinle, Erwin; Schlaich, Jörg (1996), Kuppeln aller Zeiten, aller Kulturen, Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, ISBN 3-421-03062-6

- Heinrich, Bert (1983), Brücken. Vom Balken zum Bogen, Hamburg: Rowohlt, ISBN 3-499-17711-0

- Hodge, A. Trevor (1960), The Woodwork of Greek Roofs, Cambridge University Press

- Hodge, A. Trevor (1992), Roman Aqueducts & Water Supply, London: Duckworth, ISBN 0-7156-2194-7

- Hodge, A. Trevor (2000), "Reservoirs and Dams", in ISBN 90-04-11123-9

- Huff, Dietrich (2010), "Bridges. Pre-Islamic Bridges", in Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.), Encyclopædia Iranica Online

- James, Patrick; Chanson, Hubert (2002), "Historical Development of Arch Dams. From Roman Arch Dams to Modern Concrete Designs", Australian Civil Engineering Transactions, CE43: 39–56

- Jones, Mark Wilson (1993), "One Hundred Feet and a Spiral Stair: The Problem of Designing Trajan's Column", Journal of Roman Archaeology, 6: 23–38, S2CID 250348951

- Jones, Mark Wilson (2000), Principles of Roman Architecture, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-08138-3

- Klein, Nancy L. (1998), "Evidence for West Greek Influence on Mainland Greek Roof Construction and the Creation of the Truss in the Archaic Period", Hesperia, 67 (4): 335–374, JSTOR 148449

- Kleiss, Wolfram (1983), "Brückenkonstruktionen in Iran", Architectura, 13: 105–112 (106)

- Kramers, J. H. (2010), "Shushtar", in Bearman, P. (ed.), Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.), Brill Online

- Lancaster, Lynne (1999), "Building Trajan's Column", S2CID 192986322

- Lancaster, Lynne (2008), "Roman Engineering and Construction", in ISBN 978-0-19-518731-1

- Lewis, M. J. T. (2001a), Surveying Instruments of Greece and Rome, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-79297-5

- Lewis, M. J. T. (2001b), "Railways in the Greek and Roman world", in Guy, A.; Rees, J. (eds.), Early Railways. A Selection of Papers from the First International Early Railways Conference (PDF), pp. 8–19, archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011

- Mark, Robert; Hutchinson, Paul (1986), "On the Structure of the Roman Pantheon", Art Bulletin, 68 (1): 24–34, JSTOR 3050861

- ISBN 0-415-21253-7

- Müller, Werner (2005), dtv-Atlas Baukunst I. Allgemeiner Teil: Baugeschichte von Mesopotamien bis Byzanz (14th ed.), Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN 3-423-03020-8

- Rasch, Jürgen (1985), "Die Kuppel in der römischen Architektur. Entwicklung, Formgebung, Konstruktion", Architectura, 15: 117–139

- Ruprechtsberger, Erwin M. (1999), "Vom Steinbruch zum Jupitertempel von Heliopolis/Baalbek (Libanon)", Linzer Archäologische Forschungen, 30: 7–56

- Scaife, C. H. O. (1953), "The Origin of Some Pantheon Columns", The Journal of Roman Studies, 43: 37, S2CID 161273729

- Schnitter, Niklaus (1978), "Römische Talsperren", Antike Welt, 8 (2): 25–32

- Schnitter, Niklaus (1987a), "Verzeichnis geschichtlicher Talsperren bis Ende des 17. Jahrhunderts", in Garbrecht, Günther (ed.), Historische Talsperren, vol. 1, Stuttgart: Verlag Konrad Wittwer, pp. 9–20, ISBN 3-87919-145-X

- Schnitter, Niklaus (1987b), "Die Entwicklungsgeschichte der Pfeilerstaumauer", in Garbrecht, Günther (ed.), Historische Talsperren, vol. 1, Stuttgart: Verlag Konrad Wittwer, pp. 57–74, ISBN 3-87919-145-X

- Schnitter, Niklaus (1987c), "Die Entwicklungsgeschichte der Bogenstaumauer", in Garbrecht, Günther (ed.), Historische Talsperren, vol. 1, Stuttgart: Verlag Konrad Wittwer, pp. 75–96, ISBN 3-87919-145-X

- Schörner, Hadwiga (2000), "Künstliche Schiffahrtskanäle in der Antike. Der sogenannte antike Suez-Kanal", Skyllis, 3 (1): 28–43

- Scranton, Robert L. (1938), "The Fortifications of Athens at the Opening of the Peloponnesian War", American Journal of Archaeology, 42 (4): 525–536, S2CID 191370973

- Smith, Norman (1970), "The Roman Dams of Subiaco", Technology and Culture, 11 (1): 58–68, S2CID 111915102

- Smith, Norman (1971), A History of Dams, London: Peter Davies, pp. 25–49, ISBN 0-432-15090-0

- Tudor, D. (1974), "Le pont de Constantin le Grand à Celei", Les ponts romains du Bas-Danube, Bibliotheca Historica Romaniae Études, vol. 51, Bucharest: Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România, pp. 135–166

- Ulrich, Roger B. (2007), Roman Woodworking, New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-10341-0

- Verdelis, Nikolaos (1957), "Le diolkos de L'Isthme", Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique, 81 (1): 526–529,

- Vogel, Alexius (1987), "Die historische Entwicklung der Gewichtsmauer", in Garbrecht, Günther (ed.), Historische Talsperren, vol. 1, Stuttgart: Verlag Konrad Wittwer, pp. 47–56 (50), ISBN 3-87919-145-X

- Werner, Walter (1997), "The Largest Ship Trackway in Ancient Times: the Diolkos of the Isthmus of Corinth, Greece, and Early Attempts to Build a Canal", The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 26 (2): 98–119,

- Wilson, Andrew (2002), "Machines, Power and the Ancient Economy", The Journal of Roman Studies, 92: 1–32, S2CID 154629776

- Wurster, Wolfgang W.; Ganzert, Joachim (1978), "Eine Brücke bei Limyra in Lykien", Archäologischer Anzeiger, Berlin: ISSN 0003-8105

External links

- Traianus – Technical investigation of Roman public works

- 600 Roman Aqueducts – with 40 described in detail