Lunate sulcus

| Lunate sulcus | |

|---|---|

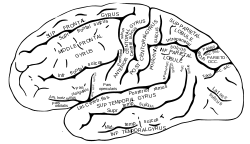

Lateral surface of left cerebral hemisphere, viewed from the side. | |

| Details | |

| Location | Occipital lobe |

| Function | Sulcus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | sulcus lunatus |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_4017 |

| TA98 | A14.1.09.134 |

| TA2 | 5483 |

| FMA | 83788 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

In brain anatomy, the lunate sulcus or simian sulcus, also known as the sulcus lunatus, is a fissure in the occipital lobe[1] variably found in humans and more often larger when present in apes and monkeys.[2] The lunate sulcus marks the transition between V1 and V2.[3]

The lunate sulcus lies further back in the human brain than in the chimpanzee's.[4] The evolutionary expansion in humans of the areas in front of the lunate sulcus would have caused a shift in the location of the fissure.[4][5] Evolutionary pressures may have resulted in the human brain undergoing internal reorganization to develop the capability of language.[6] It has been speculated that this reorganization is implemented during early maturity and is responsible for eidetic imagery in some adolescents.[6]

During early development, the neural connections in prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal lobe rapidly expand to allow capability for human language, while

History

The lunate sulcus was first identified during the early 1900s in the human brain as a

Smith’s observation that the caudal shift of the lunate sulcus could also be used as a predictor for determining both the evolutionary posterolateral shift of the occipital lobes/V1 and the corresponding expansion of the neighboring parietotemporo-occipital visual association cortices was supported by recent research.[9][10] However, some neuroanatomists today disagree with Smith’s assertion that a lunate sulcus exists in humans, arguing that there is only an Affenspalte which is unique to apes. Specifically, in a high-resolution MRI study conducted by Allen et al. (2006), the researchers scanned and analyzed 220 human brains and found no sign of the lunate sulcus homologue. Based on this finding, they suggested that the claim asserting humans have a lunate sulcus homologue fails to account for and show appreciation of the extensive evolutionary reorganization of the visual cortex in humans.[1]

Evolution

Analyzing variability in the location of gross

References

- ^ PMID 16835937.

- PMID 18516336.

- ^ Schmolesky, M. "The organization of the retina and visual system".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c Rincon, Paul (2004). "Human brain began evolving early". BBC.

- ^ a b Bruner, E (2014). Human paleoneurology. Springer.

- ^ .

- PMID 15148381.

- S2CID 4428635.

- ^ PMID 24822043.

- ^ PMID 20172590.

- .

- S2CID 3359887.

- ^ .

- S2CID 142597701.

- PMID 12050080.