Motor protein

Motor proteins are a class of

Cellular functions

Motor proteins are the driving force behind most

Diseases associated with motor protein defects

The importance of motor proteins in cells becomes evident when they fail to fulfill their function. For example,

Cytoskeletal motor proteins

Motor proteins utilizing the

There are two basic types of microtubule motors: plus-end motors and minus-end motors, depending on the direction in which they "walk" along the microtubule cables within the cell.

Actin motors

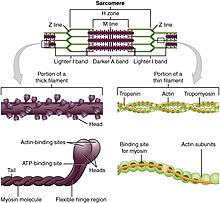

Myosin

Genomic representation of myosin motors:[6]

- Fungi (yeast): 5

- Plants (Arabidopsis): 17

- Insects (Drosophila): 13

- Mammals (human): 40

- Chromadorea ( nematode C. elegans): 15

Microtubule motors

Kinesin

Genomic representation of kinesin motors:[6]

- Fungi (yeast): 6

- Plants (Arabidopsis thaliana): 61

- Insects (Drosophila melanogaster): 25

- Mammals (human): 45

Dynein

Genomic representation of dynein motors:[6]

- Fungi (yeast): 1

- Plants (Arabidopsis thaliana): 0

- Insects (Drosophila melanogaster): 13

- Mammals (human): 14-15

Plant-specific motors

In contrast to

Another motor protein essential for plant cell division is kinesin-like calmodulin-binding protein (KCBP), which is unique to plants and part kinesin and part myosin.[13]

Other molecular motors

Besides the motor proteins above, there are many more types of proteins capable of generating forces and torque in the cell. Many of these molecular motors are ubiquitous in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, although some, such as those involved with cytoskeletal elements or chromatin, are unique to eukaryotes. The motor protein prestin,[14] expressed in mammalian cochlear outer hair cells, produces mechanical amplification in the cochlea. It is a direct voltage-to-force converter, which operates at the microsecond rate and possesses piezoelectric properties.

See also

References

- PMID 14559185.

- ^ Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (2002-01-01). "Molecular Motors". NCBI - National Institutes of Health.

- PMID 22291143.

- PMID 22566666.

- S2CID 635349.

- ^ PMID 12600311.

- PMID 21332353.

- PMID 16084724.

- PMID 24064538.

- S2CID 14240073.

- PMID 16530461.

- PMID 11909547.

- PMID 15951483.

- S2CID 7333228.

External links

- MBInfo - What are Motor Proteins?

- Ron Vale's Seminar: "Molecular Motor Proteins"

- Biology of Motor Proteins Biophysical Chemistry, Göttingen

- Jonathan Howard (2001), Mechanics of motor proteins and the cytoskeleton. ISBN 9780878933334