Observations and explorations of Venus

The planet Venus was first observed in antiquity, and continued with telescopic observations, and then by visiting spacecraft. Spacecraft have performed multiple flybys, orbits, and landings on the planet, including balloon probes that floated in its atmosphere. Study of the planet is aided by its relatively close proximity to the Earth, but the surface of Venus is obscured by an atmosphere opaque to visible light.

Ground-based observations

Transits of Venus directly between the Earth and the Sun's visible disc are rare astronomical events. The first such transit to be predicted and observed was the 1639 transit of Venus, seen and recorded by English astronomers Jeremiah Horrocks and William Crabtree.[1] The observation by Mikhail Lomonosov of the transit of 1761 provided the first evidence that Venus had an atmosphere, and the 19th-century observations of parallax during Venus transits allowed the distance between the Earth and Sun to be accurately calculated for the first time.[2] Transits can only occur either in early June or early December, these being the points at which Venus crosses the ecliptic (the orbital plane of the Earth), and occur in pairs at eight-year intervals, with each such pair more than a century apart. The most recent pair of transits of Venus occurred in 2004 and 2012, while the prior pair occurred in 1874 and 1882.[3]

In the 19th century, many observers stated that Venus had a period of rotation of roughly 24 hours. Italian astronomer

. Accuracy was refined at each subsequent conjunction, primarily from measurements made from Goldstone and Eupatoria. The fact that rotation was retrograde was not confirmed until 1964.Before radio observations in the 1960s, many believed that Venus contained a lush, Earth-like environment. This was due to the planet's size and orbital radius, which suggested a fairly Earth-like situation as well as to the thick layer of clouds which prevented the surface from being seen. Among the speculations on Venus were that it had a jungle-like environment or that it had oceans of either petroleum or carbonated water.[5] However, microwave observations by C. Mayer et al.[6] indicated a high-temperature source (600 K). Strangely, millimetre-band observations made by A. D. Kuzmin indicated much lower temperatures.[7] Two competing theories explained the unusual radio spectrum, one suggesting the high temperatures originated in the ionosphere, and another suggesting a hot planetary surface.

In September 2020, a team at Cardiff University announced that observations of Venus using the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope and Atacama Large Millimeter Array in 2017 and 2019 indicated that the Venusian atmosphere contained phosphine (PH3) in concentrations 10,000 times higher than those that could be ascribed to any known non-biological source on Venus. The phosphine was detected at heights of at least 30 miles (48 kilometres) above the surface of Venus, and was detected primarily at mid-latitudes with none detected at the poles of Venus. This could have indicated the potential presence of biological organisms on Venus,[8][9] however, this measurement was later shown to be in error.[10][11]

Terrestrial radar mapping

After the Moon, Venus was the second object in the

Interest in the

Observation by spacecraft

There have been numerous uncrewed missions to Venus. Ten Soviet Venera probes achieved a soft landing on the surface, with up to 110 minutes of communication from the surface, all without return.[15] Launch windows occur every 19 months.[16]

Early flybys

On February 12, 1961, the

The first successful flyby Venus probe was the American Mariner 2 spacecraft, which flew past Venus in 1962, coming within 35,000 km. A modified Ranger Moon probe, it established that Venus has practically no intrinsic magnetic field and measured the temperature of the planet's atmosphere to be approximately 500 °C (773 K; 932 °F).[18]

The Soviet Union launched the Venera 2 probe to Venus in 1966, but it malfunctioned sometime after its May 16 telemetry session. The probe completed a flyby of Venus, but failed to transmit any data.[17]

During another American flyby in 1967, Mariner 5 measured the strength of Venus's magnetic field. In 1974, Mariner 10 swung by Venus on its way to Mercury and took ultraviolet photographs of the clouds, revealing the extraordinarily high wind speeds in the Venusian atmosphere. Mariner-10 provided the best images of Venus taken so far, the series of images clearly demonstrated the high speeds of the planet's atmosphere, first seen in the Doppler-effect velocity measurements of Venera-4 through Venera-8.[19]

Early landings

On March 1, 1966, the

The descent capsule of Venera 4 entered the atmosphere of Venus on October 18, 1967, making it the first probe to return direct measurements from another planet's atmosphere.[17] The capsule measured temperature, pressure, density and performed 11 automatic chemical experiments to analyze the atmosphere. It discovered that the atmosphere of Venus was 95% carbon dioxide (CO

2), and in combination with radio occultation data from the Mariner 5 probe, showed that surface pressures were far greater than expected (75 to 100 atmospheres).[citation needed]

These results were verified and refined by the Venera 5 and Venera 6 in May 1969.[17] But thus far, none of these missions had reached the surface while still transmitting. Venera 4's battery ran out while still slowly floating through the massive atmosphere, and Venera 5 and 6 were crushed by high pressure 18 km (60,000 ft) above the surface.[citation needed]

The first successful landing on Venus was by

Lander/orbiter pairs

Venera 9 and 10

The Soviet probe Venera 9 entered orbit on October 22, 1975, becoming the first artificial satellite of Venus. A battery of cameras and spectrometers returned information about the planet's clouds, ionosphere and magnetosphere, as well as performing bi-static radar measurements of the surface. The 660 kg (1,460 lb) descent vehicle[25] separated from Venera 9 and landed, taking the first pictures of the surface and analyzing the crust with a gamma ray spectrometer and a densitometer. During descent, pressure, temperature and photometric measurements were made, as well as backscattering and multi-angle scattering (nephelometer) measurements of cloud density. It was discovered that the clouds of Venus are formed in three distinct layers.[citation needed]

On October 25, Venera 10 arrived and carried out a similar program of study.

Pioneer Venus

In 1978, NASA sent two Pioneer spacecraft to Venus. The Pioneer mission consisted of two components, launched separately: an orbiter and a multiprobe. The Pioneer Venus Multiprobe carried one large and three small atmospheric probes. The large probe was released on November 16, 1978, and the three small probes on November 20. All four probes entered the Venusian atmosphere on December 9, followed by the delivery vehicle. Although not expected to survive the descent through the atmosphere, one probe continued to operate for 45 minutes after reaching the surface. The Pioneer Venus Orbiter was inserted into an elliptical orbit around Venus on December 4, 1978. It carried 17 experiments and operated until the fuel used to maintain its orbit was exhausted and atmospheric entry destroyed the spacecraft in August 1992.

Further Soviet missions

Also in 1978,

In 1982, the Soviet Venera 13 sent the first colour image of Venus's surface, revealing an orange-brown flat bedrock surface covered with loose regolith and small flat thin angular rocks,[29] and analysed the X-ray fluorescence of an excavated soil sample. The probe operated for a record 127 minutes on the planet's hostile surface. Also in 1982, the Venera 14 lander detected possible seismic activity in the planet's crust.

In December 1984, during the apparition of

The multiaimed Soviet

Orbiters

Venera 15 and 16

In October 1983,

Magellan

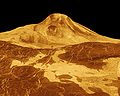

On August 10, 1990, the American

The resulting maps were comparable to visible-light photographs of other planets, and are still the most detailed in existence. Magellan greatly improved scientific understanding of the geology of Venus: the probe found no signs of plate tectonics, but the scarcity of impact craters suggested the surface was relatively young, and there were lava channels thousands of kilometers long. After a four-year mission, Magellan, as planned, plunged into the atmosphere on October 11, 1994, and partly vaporized; some sections are thought to have hit the planet's surface.

Venus Express

Venus Express successfully assumed a polar orbit on April 11, 2006. The mission was originally planned to last for two Venusian years (about 500 Earth days), but was extended to the end of 2014 until its propellant was exhausted. Some of the first results emerging from Venus Express include evidence of past oceans, the discovery of a huge double atmospheric vortex at the south pole,[32][33] and the detection of hydroxyl in the atmosphere.

Akatsuki

Flybys

Several space probes en route to other destinations have used flybys of Venus to increase their speed via the

MESSENGER passed by Venus twice on its way to Mercury. The first time, it flew by on October 24, 2006, passing 3000 km from Venus. As Earth was on the other side of the Sun, no data was recorded.[38] The second flyby was on July 6, 2007, where the spacecraft passed only 325 km from the cloudtops.[39]

BepiColombo also flew by Venus twice on its way to Mercury, the first time on October 15, 2020. During its second flyby of Venus, on August 10, 2021, BepiColombo came 552 km near Venus's surface.[40][41][42][43] While BepiColombo approached Venus before making its second flyby of the planet, two monitoring cameras and seven science instruments were switched on.[44] Johannes Benkhoff, project scientist, believes BepiColombo's MERTIS (Mercury Radiometer and Thermal Infrared Spectrometer) could possibly detect phosphine, but "we do not know if our instrument is sensitive enough".[45]

Parker Solar Probe has performed seven Venus flybys, which occurred on October 3, 2018, December 26, 2019, July 11, 2020, February 20, 2021, October 16, 2021, August 21, 2023, and November 6, 2024. Parker Solar Probe makes observations of the Sun and solar wind, and these Venus encounters enable Parker Solar Probe to perform gravity assists and travel closer to the Sun.[46][47]

Future missions

The

India's ISRO is developing Venus Orbiter Mission, an orbiter and an atmospheric probe with a balloon aerobot which is planned to launch in 2028.[49]

In June 2021, NASA announced the selection of two new Venus spacecraft, both part of its

In June 2021, soon after NASA announced VERITAS and DAVINCI,

On October 6, 2021, the United Arab Emirates announced its intention to send a probe to Venus as early as 2028. MBR Explorer would make observations of the planet while using it for a gravity assist to propel it to the asteroid belt.[60]

Proposals

To overcome the high pressure and temperature at the surface, a team led by

In 2020 NASA's JPL launched an open competition, titled "Exploring Hell: Avoiding Obstacles on a Clockwork Rover", to design a sensor that could work on Venus's surface.[65]

Current missions

| Mission | Launch | Arrival | Termination | Objective |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| February 9, 2020 | 26 December 2020 (1st flyby) |

ongoing | 8 flybys during gravity-assist maneuvers from 2020 to 2030 |

Planned missions

| Name | Operator | Proposed launch year |

Type | Status | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venus Life Finder | NET summer 2026 | Atmospheric probe | under development | [66] | |

| MBR Explorer | UAESA

|

2028 | Flyby | under development | [67][68] |

| Venus Orbiter Mission | 29 March 2028[69] | Orbiter/atmospheric probe | under development | [70] | |

| VERITAS | 2031 | Orbiter | under development | [71][72] | |

| DAVINCI | 2031–2032 | Atmospheric probe | under development | [71][73] | |

EnVision

|

ESA

|

2031–2032 | Orbiter | under development | [74] |

Impact

Research on the atmosphere of Venus has produced significant insights not only about its own state but also about the atmospheres of other

The voyage of James Cook and his crew of HMS Endeavour to observe the Venus transit of 1769 brought about the claiming of Australia at Possession Island for colonisation by Europeans.

See also

References

- ^ Naeye, Robert (June 1, 2012). "Transits of Venus in History: 1631-1716".

- ^ "Transit of Venus 2012 Articles". sunearthday.nasa.gov.

- ^ Simion, Florin. "Transits of Venus". The Royal Astronomical Society. Retrieved 6 February 2025.

- ^ "The Rotation of Venus | Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian". www.cfa.harvard.edu.

- ISSN 1572-9672. Retrieved 6 February 2025.

- doi:10.1086/146433.

- ^ Kuz'min, A. D.; Marov, M. Y. (1 June 1975). "Fizika Planety Venera" [Physics of the Planet Venus]. "Nauka" Press. p. 46. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

The lack of evidence that the Venusian atmosphere is transparent at 3 cm wavelength range, the difficulty of explaining such a high surface temperature, and a much lower brightness temperature measured by Kuz'min and Salmonovich [80, 81] and Gibson [310] at a shorter wavelength of 8 mm all provided a basis for a different interpretation of the radio astronomy measurement results offered by Jones [366].

- S2CID 221655755. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ Sample, Ian (14 September 2020). "Scientists find gas linked to life in atmosphere of Venus". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "Is the Phosphine Biosignature on Venus a Calibration Error?". Sky & Telescope. 17 November 2020.

- S2CID 224803085.

- ^ "Venus - Atmosphere, Orbit, Surface | Britannica". www.britannica.com. January 30, 2025.

- PMID 17743054– via science.org (Atypon).

- doi:10.1086/110941.

- ^ "Soviet Venus Missions". astro.if.ufrgs.br. Retrieved 6 February 2025.

- ^ "Missions to Venus". mentallandscape.com. Retrieved 6 February 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Adler, Doug (9 May 2025). "Behind the Iron Curtain: The Soviet Venera program". Astronomy Magazine. Retrieved 14 May 2025.

- ^ "Mariner 2". 6 March 2015.

- ^ "First Pictures of the Surface of Venus". mentallandscape.com. Retrieved 2024-11-16.

- ^ "Science: Onward from Venus". Time. 8 February 1971. Archived from the original on December 21, 2008. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- LCCN 2017059404. SP2018-4041.

- ^ "Venera 7". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Venera 8". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Venera 9's landing site". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ Braeunig, Robert A. (2008). "Planetary Spacecraft". Archived from the original on 2017-03-20. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ^ "A history of the search for life on Venus". www.skyatnightmagazine.com. 14 September 2020. Retrieved 2024-11-20.

- ^ "The Venera 11 & 12 probes to Venus". heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2024-11-20.

- ^ "Venera 11 descent craft". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Venera 13". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- doi:10.1109/5.90157.

- ^ "Catalog Page for PIA00160". photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2024-11-17.

- ^ "500 days at Venus, and the surprises keep coming". www.esa.int. Retrieved 6 February 2025.

- ^ "ESA Science & Technology - Venus Express: mission overview". sci.esa.int. Retrieved 6 February 2025.

- ^ "Live from Sagamihara: Akatsuki Orbit Insertion - Second Try".

- New York Times. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^

Hand, Eric (2007-11-27). "European mission reports from Venus". Nature (450): 633–660. S2CID 129514118.

- ^ "Venus offers Earth climate clues". BBC News. November 28, 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-29.

- ^ "MESSENGER performs first flyby of Venus". NASA's Solar System Exploration: News & Events: News Archive. Archived from the original on 2008-10-05. Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- ^ "MESSENGER performs second flyby of Venus". NASA's Solar System Exploration: News & Events: News Archive. Archived from the original on 2008-10-05. Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- ^ "BepiColombo's second Venus flyby in images". European Space Agency. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ Pultarova, Tereza (August 11, 2021). "Mercury-bound spacecraft snaps selfie with Venus in close flyby (photo)". Space.com. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ "BepiColombo flies by Venus en route to Mercury". ESA. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ ""A flawless, radiant, #Mercuryflyby"". Twitter. 1 October 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ "BepColombo Venus Flybys". European Space Agency. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ O'Callaghan, Jonathan. "In A Complete Fluke, A European Spacecraft Is About To Fly Past Venus – And Could Look For Signs Of Life". Forbes. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ "Final Venus Flyby for NASA's Parker Solar Probe Queues Closest Sun Pass - NASA Science". NASA. 4 November 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2025.

- PMID 35864851.

- ^ Zak, Anatoly (5 March 2021). "New promise for the Venera-D project". RussianSpaceWeb. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ISSN 0013-0389. Retrieved 2024-01-16.

Somanath also said there is a good opportunity to launch a mission to explore planet Venus by 2028.

- ^ Johnson, Alana; Fox, Karen. "NASA Selects 2 Missions to Study 'Lost Habitable' World of Venus". NASA. Archived from the original on 13 February 2024. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (2 June 2021). "New NASA Missions Will Study Venus, a World Overlooked for Decades". New York Times. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- Bibcode:2012AGUFM.P33C1950H.

- ^ Steigerwald, William; Jones, Nancy Neal (2 June 2021). "NASA to Explore Divergent Fate of Earth's Mysterious Twin with Goddard's DAVINCI+". NASA. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (8 November 2023). "VERITAS mission warns of risks of launch delay". SpaceNews. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ Roulette, Joey (2 June 2021). "NASA will send two missions to Venus for the first time in over 30 years". The Verge. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (10 June 2021). "Europe will join the space party at Planet Venus". BBC News. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "EnVision: Understanding why Earth's closest neighbour is so different" (PDF). ESA. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ EnVision: Understanding why our most Earth-like neighbor is so different. M5 proposal. Richard Ghail. arXiv.org

- ^ Venus Evolution Through Time: Key Science Questions, Selected Mission Concepts and Future Investigations T. Widemann, S. Smrekar, J. Garvin et al., Space Science Reviews, vol. 219, no 56, 3 octobre 2023 (DOI: 10.1007/s11214-023-00992-w)

- ^ Ryan, Jackson (October 6, 2021). "Daring mission to Venus and the asteroid belt announced by the UAE". cnet.com. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (31 October 2023). "Rocket Lab plans launch of Venus mission as soon as late 2024". SpaceNews. Retrieved 7 February 2024.

- .

- ^ "To conquer Venus, try a plane with a brain". NewScience. Retrieved 2007-09-03.

- .

- ^ Holly Yan (2020). "Here's your chance to design equipment for NASA's proposed Venus rover and win $15,000". CNN. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ "Rocket Lab Mission to Venus". Venus Missions. Retrieved February 28, 2025.

- ^ Howell, Elizabeth (28 May 2023). "UAE Asteroid Mission details". Space.com.

- ^ Davis, Leonard (4 September 2024). "UAE on track to launch bold 7-asteroid mission in 2028". Space.com.

- ^ "Isro announces launch date of ambitious Venus Orbiter Mission". India Today. 2024-10-01. Retrieved 2024-10-02.

- ^ Jones, Andrew (18 September 2024). "India approves moon sample return, Venus orbiter, space station module and reusable launcher". SpaceNews. Retrieved 18 September 2024.

- ^ a b Devarakonda, Yaswant (25 March 2024). "The FY25 Presidential Budget Request for NASA". American Astronomical Society. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ Howell, Elizabeth (4 November 2022). "Problems with NASA asteroid mission Psyche delay Venus probe's launch to 2031". Space.com. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Neal Jones, Nancy (2 June 2022). "NASA's DAVINCI Mission To Take the Plunge Through Massive Atmosphere of Venus". NASA. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ESA. 10 June 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Frank Mills (September 15, 2012). "What Venus has taught us about protecting the ozone layer". theConversation.com. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

Further reading

- Widemann, Thomas; et al. (October 2023). "Venus Evolution Through Time: Key Science Questions, Selected Mission Concepts and Future Investigations". Space Science Reviews. 219 (7): 56. hdl:10852/109541.