Palaeoloxodon

| Palaeoloxodon Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton of the straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus) at the paleontological museum of the Sapienza University of Rome | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Clade: | Elephantida |

| Superfamily: | Elephantoidea |

| Family: | Elephantidae |

| Genus: | †Palaeoloxodon Matsumoto, 1924[1] |

| Type species | |

| Elephas namadicus naumanni Makiyama, 1924

| |

| Species | |

|

See text | |

Palaeoloxodon is an extinct

Taxonomy

Prior to the description of the genus, Palaeoloxodon species were initially placed in the genus

Palaeoloxodon was often historically considered to be a

Analysis of mitochondrial genomes, including Palaeoloxodon individuals from Northern China indicates Palaeoloxodon individuals harboured multiple separate mitochondrial genome lineages derived from African forest elephants, some being more closely related to some West African forest elephant groups than to others. It is unclear as to whether this is the result of multiple hybridisation events, or whether multiple mitochondrial lineages were introgressed in a single event. It has been found that mitochondrial genome of Chinese Palaeoloxodon specimens clustered with a P. antiquus individual from western Europe, which belonged to a separate clade than other sampled European P. antiquus specimens. The relatively low divergence between the mitochondrial genomes of the European P. antiquus individual and the Chinese Palaeoloxodon specimens may indicate that the populations of Palaeoloxodon across Eurasia maintained gene flow with each other, but this is uncertain.[6]

Diagram of the relationships of elephant mitochondrial genomes, after Lin et al. 2023:[6]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mainland species

- P. recki (Synonym: Elephas recki) (East Africa), the oldest species and ancestor of all later species

- P. jolensis(Synonym: Elephas iolensis) the last (late Middle-Late Pleistocene) representative of Palaeoloxodon in Africa

- P. antiquus(Synonym: Elephas antiquus) (Straight tusked elephant) (Europe, Western Asia)

- P. huaihoensis (China)

- P. namadicus (Synonym: Elephas namadicus)[7] (Indian subcontinent, possibly also elsewhere in Asia), the largest in its genus, and possibly the largest terrestrial mammal ever

- P. naumanni (Synonym: E. namadicus naumanni) (Japan, possibly also China and Korea),[8]

- ?P. turkmenicus known from a single specimen found in the Middle Pleistocene of Turkmenistan, with possibly attributable remains known from Kashmir, validity uncertain.[9]

Mediterranean island dwarfs

These Mediterranean insular dwarf elephant species are almost certainly descended from P. antiquus

- P. creutzburgi (Crete)

- P. xylophagou (Cyprus)

- P. cypriotes (Cyprus)

- P. lomolinoi (Naxos)

- P. tiliensis (Tilos)

- P. mnaidriensis (Sicily and Malta)

- P. falconeri (Sicily and Malta)

Other indeterminate dwarf Palaeoloxodon species are known from other Greek islands, including Rhodes and Kasos.[10]

Description

Most species of Palaeoloxodon are noted for their distinctive parieto-occipital crests present at the top of the cranium. The crest functioned to anchor muscle tissue, including the splenius as well as an additional muscle layer called the "extra splenius" (which was likely similar to the "splenius superficialis" found in Asian elephants, and which may have been an extension of the rhomboideus cervicis muscle) which wrapped around the top of the head to support it. The development of the crest is variable depending on the species, growth stage and gender, with females and juveniles having less developed or absent crests. The crest likely developed as a response to the large size of the head, which in proportional and absolute terms are the largest in size of any proboscideans.[9] The skull is proportionally short and tall,[11] with the premaxillary bones containing the tusks being flared outwards. The tusks have relatively little curvature, and are proportionally large,[9] and somewhat twisted, with the tusk alveoli (sockets) being divergent from each other at least in Pleistocene species.[11] These tusks could reach 4 metres (13 ft) in length, and probably over 190 kilograms (420 lb) in weight in the largest species, larger than any recorded in modern elephants.[12]

The molar teeth of Palaeoloxodon species typically show a "dot-dash-dot" wear pattern,

Species of Palaeoloxodon varied widely in size. Large bulls of

-

Life restoration of Palaeoloxodon namadicus

-

Skeletal diagram of an adult malePalaeoloxodon antiquus

-

Third molar teeth of Palaeoloxodon huaihoensis

-

Partial skull of Palaeoloxodon namadicus, showing the parieto-occipital crest at the top of the skull

-

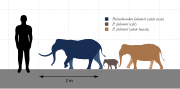

Size comparison of the dwarf elephant Palaeoloxodon falconeri, one of the smallest elephants known

-

Skull of Palaeoloxodon antiquus in front-on view, showing flared premaxillae with divergent tusks

Ecology

Species of Palaeoloxodon are thought to have similar social behaviour to modern elephants, with herds of adult females and juveniles, as well as solitary adult males.[17] The African species of Palaeoloxodon, as well as P. namadicus are suggested to have been grazers,[18][19] while P. antiquus is suggested to have been a variable mixed feeder that consumed a considerable amount of browse.[20]

Evolution

Palaeoloxodon first unambiguously appears in the fossil record in Africa during the

Extinction

The timing of the extinction of the last Paleoloxodon species in Africa,

Relationship with humans

Remains of the species P. recki, P. antiquus and P. naumanni have been found associated at a number of sites with stone stools and/or with cut marks on their bones, indicating that they were butchered, with some sites presenting clear evidence of hunting. These sites span from the Early Pleistocene, at least 1.3 but possibly as early as 1.6 million years ago to around 40,000 years ago, with the makers of the sites including both archaic humans (P. antiquus and P. recki) and modern humans (P. naumanni).[31][32][33]

References

- ^ .

- ^ .

- .

- PMID 28585920.

- PMID 29483247.

- ^ PMID 37463654.

- ^ Kevrekidis, C., & Mol, D. (2016). A new partial skeleton of Elephas (Palaeoloxodon) antiquus Falconer and Cautley, 1847 (Proboscidea, Elephantidae) from Amyntaio, Macedonia, Greece. Quaternary International, 406, 35–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.11.110

- ISBN 9781119675730.

- ^ S2CID 213676377.

- ^ S2CID 199107354.

- ^ S2CID 245067102, retrieved 2023-07-16

- ISSN 0891-2963.

- S2CID 134216492.

- ISSN 0031-0182.

- ISSN 2571-550X.

- ^ S2CID 181855906.

- PMID 34531420.

- ^ S2CID 198190671.

- S2CID 210307849.

- S2CID 200073388.

- ISBN 978-1-315-11891-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-78570-965-4, retrieved 2020-04-14

- PMID 33954049.

- S2CID 216504699.

- .

- S2CID 228877664.

- S2CID 234265221.

- ISSN 0277-3791.

- S2CID 225710152.

- ISSN 1040-6182.

- ISSN 2571-550X.

- .

- .