Payún Matrú

| Payún Matrú | |

|---|---|

Payún Matrú | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 3,715 m (12,188 ft)[1] |

| Coordinates | 36°25′19″S 69°14′28″W / 36.422°S 69.241°W[1] |

| Geography | |

| Parent range | Andes |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Shield volcano |

| Last eruption | 445 ± 50 years ago |

Payún Matrú is a

Payún Matrú developed on sediment and volcanic rocks ageing from the

Volcanic activity at Payún Matrú commenced during the Plio-Pleistocene period, and generated lava fields such as Pampas Onduladas, the Payún Matrú shield volcano and the Payun volcano. After the formation of the caldera, volcanism continued both within the caldera as lava domes and flows, and outside of it with the formation of scoria cones and lava flows east and especially west of Payún Matrú. Volcanic activity continued into the Holocene until about 515 years ago; oral tradition of local inhabitants contains references to earlier eruptions.

Name

In local dialect, the term Payún or Paium means "bearded", while the term Matru translates as "goat".[2] The field is sometimes also known as Payenia.[3]

Geography and geomorphology

Regional

Payún Matrú lies in the

The active field is part of the

Local

Payún Matrú is a 15 km-wide (9.3 mi)

A 7–8 km-long (4.3–5.0 mi)

Matrú's highest active point field is the

-

The Payun volcano

-

The Payun volcano

-

Payún Matrú seen from space

Payún Matrú volcanic field

Aside from the caldera, the field contains about 300 individual

Older lava flows have

The cones are aligned along easterly or northeasterly lineaments[19] which correlate with geological structures in the basement,[39] and appear to reflect the tectonic stresses underground.[40] Among these lineaments is the La Carbonilla fracture which runs in east–west direction and crops out in the eastern part of the field; in the central sector it is hidden by the caldera and in the western it is buried by lava flows.[41] The La Carbonilla fracture is a fault[40] that appears to have been an important influence on the development of the Payún Matrú complex in general.[42] Fissural ridges and elongated chains of vents and cones highlight the control that lineaments exercise on the volcanic eruptions.[43] In the summit area, pumice cones are aligned along the caldera rim.[44]

Among the cones in Payún Matrú are the

- Los Morados is a complex of scoria cones and vents of different agesStrombolian activity and a lava flow-induced rafting and re-healing of its slopes.[50]

- On the southeast and east Los Morados is bordered by a lapilli plain, the Pampas Negras,[51] which was formed by fallout of Strombolian eruptions and is being reworked by wind with the formation of dunes.[32]

- Morado Sur consists of two aligned cones that formed in the same eruption and are covered with reddish deposits;[52] it also features several vents and lava flows.[53]

- Volcán Santa María is a cone with a small crater and also covered with red lava bombs.[54] It is 180 m (590 ft) high and is associated with an area called "El Sandial", where lava bombs have left traces such as impact craters and aerodynamically deformed rocks.[55]

Pampas Onduladas and other giant lava flows

Payún Matrú is the source of the longest

This compound lava flow moved over a gentle terrain

Together with the Þjórsá Lava in Iceland and the Toomba and Undara lava flows in Queensland, Australia, it is one of only a few Quaternary lava flows that reached a length of over 100 km (62 mi)[57] and it has been compared to some long lava flows on Mars.[66] Southwest from Pampas Onduladas lie the 181.2 kilometres (112.6 mi) long Los Carrizales lava flows, which have in part advanced to even larger distances than Pampas Onduladas but owing to a straighter course are considered to be shorter than the Pampas Onduladas lava flow,[67][68] and the La Carbonilla lava flow which like Los Carrizales propagated southeastward and is located just west from the latter.[51] Additional large lava flows are located in the western part of the field and resemble the Pampas Onduladas lava flow, such as the El Puente Formation close to the Rio Grande River of possibly recent age.[37] Long lava flows have also been produced by volcanic centres directly south of Payún Matrú,[69] including the 70–122 km (43–76 mi) long El Corcovo, Pampa de Luanco and Pampa de Ranquelcó flows.[70][71]

Hydrography and non-volcanic landscape

Apart from the lake in the caldera, the area of Payún Matrú is largely devoid of permanent water sources, with most water sites that draw in humans being either temporary so-called "toscales" or ephemeral.

Geology

West of South America, the

There is evidence of Precambrian[78] (older than 541 ± 0.1 million years ago[45]) and Permian-Triassic (298.9 ±0.15 to 201.3 ±0.2 million years ago[45]) volcanism (Choique Mahuida Formation)[79] in the region, but a long hiatus separates them from the recent volcanic activity which started in the Pliocene (5.333–2.58 million years ago[45]). At that time, the basaltic El Cenizo Formation and the andesitic Cerro El Zaino volcanics were emplaced.[80] This kind of calcalkaline volcanic activity is interpreted to be the consequence of flat slab subduction during the Miocene (23.03-5.333 million years ago[45]) and Pliocene,[13] and took place between twenty and five million years ago.[76] Later during the Pliocene and Quaternary the slab steepened, and probably as a consequence volcanism in the land above increased,[81] reaching a peak between eight and five million years ago.[15]

Local

The basement rock underneath Payún Matrú is formed by

Payún Matrú is part of the

Other volcanic fields in the region are the

Lava and magma composition

The volcanic field has produced rocks with composition ranging from

Volcanic rocks erupted at Payún Matrú resemble

The magma ejected at Payún Matrú originates during

Climate, soils and vegetation

The climate at Payún Matrú is cold and dry

The vegetation in the volcanic field is mostly characterized by sparse

Eruptions

The geological history of the Payún Matrú volcanic field is poorly dated

The first volcanic activity occurred west and east of Payún Matrú and involved the emission of olivine basalt lava flows.[40] The long Pampas Onduladas lava flow was erupted 373,000 ± 10,000 years ago[116] and buried parts of the 400,000 ± 100,000 years old Los Carrizales lava field;[37] both have hawaiitic composition.[117] The Payun volcano formed around 265,000 ± 5,000 years ago within a timespan of about 2,000–20,000 years.[35] Its inferred eruption rate of 0.004 km3/ka (0.00096 cu mi/ka) is similar to typical volcanic arc eruption rates such as at Mount St. Helens.[29]

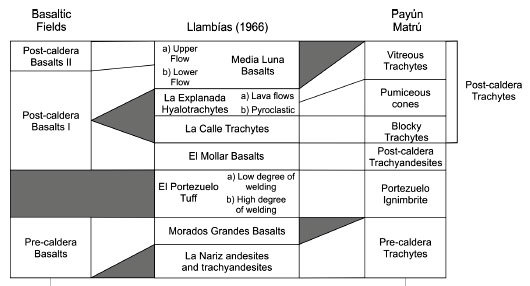

The main Payún Matrú massif formed in about 600,000 years, with the oldest trachytic rocks dated to 700,000 years ago. It is comprised by the lavic and ignimbritic Pre-caldera Trachyte unit[23] and consists of trachyandesitic to trachytic rocks, with trachyte being the most important component.[13] The massif may have formed a tall edifice like the Payun volcano before caldera collapse.[68]

The formation of the caldera coincides with the eruption of the Portezuelo Ignimbrite[41]/Portezuelo Formation[17] and took place between 168,000 ± 4,000 and 82,000 ± 2,000 years ago.[e][34] This ignimbrite formation where it is not buried by younger eruption products[119] spreads radially around the caldera and reaches a maximum exposed thickness of 25 metres (82 ft);[24] it covers an area of about 2,200 km2 (850 sq mi) on the northern and southern sides of Payún Matrú,[17] and its volume is estimated to be about 25–33 km3 (6.0–7.9 cu mi).[119] The event was probably precipitated by the entry of mafic magma in the magma chamber and its incomplete mixing with pre-existent magma chamber melts,[95] or by tectonic processes;[103] the resulting Plinian eruption generated an eruption column, which collapsed, producing the ignimbrites.[17] Different layers of magma in the magma chamber were erupted during the course of the eruption[120] and eventually the summit of the volcano collapsed as well, forming the caldera; activity continued and emplaced lava domes[17] and lava flows in the caldera area. These post-caldera volcanic formations are subdivided into three separate lithofacies.[119]

Basaltic and trachyandesitic activity continued after the formation of the caldera.[1] Morphology indicates that the El Rengo and Los Volcanes volcanic cones appear to be of Holocene age, while the Guadaloso vents formed during the Plio-Pleistocene.[17] One age from the eastern side is 148,000 ± 9,000 years ago, it comes from northeast of the Payún Matrú caldera.[121]

Uneroded volcanic cones and dark basaltic lavas indicate that activity continued into the Holocene.

Various dating methods have yielded various ages for late Pleistocene-Holocene volcanic eruptions:

- 44,000 ± 2,000 years ago, surface exposure dating.[127]

- 43,000–41,000 ± 3,000 years ago, surface exposure dating, El Puente Formation. Basaltic lava flows of this formation reach ages of about 320,000 ± 5,000 years, implying a prolonged history of emplacement.[128]

- 41,000 ± 1,000 years ago, underlying the Los Morados lava flow.[129]

- 37,000 ± 3,000 years ago, surface exposure dating,[127] close to the Rio Grande River.[51]

- 37,000 ± 1,000 years ago, La Planchada fallout deposit.[130]

- 37,000 ± 2,000 years ago, northwestern side of the caldera.[131]

- 28,000 ± 5,000 years ago, potassium-argon dating, lava flow[130] on the westerly side.[132]

- 26,000 ± 5,000 years ago, potassium-argon dating, close to the Rio Grande.[132]

- 26,000 ± 2,000 years ago, potassium-argon dating, not the same as the 26,000 ± 5,000 flow.[132]

- 26,000 ± 1,000 years ago, potassium-argon dating, rhyolitic lava flow in the La Calle group.[130]

- 20,000 ± 7,000 years ago, north of the Payún Matrú caldera.[121]

- 16,000 ± 1,000 years ago, underlying the Los Morados lava flow.[129]

- 15,200 ± 900 years ago,[133] potassium-argon dating, lava flow on the northwesterly[130]-westerly side.[132]

- 9,000 years ago, potassium-argon dating.[127]

- 7,000 ± 1,000 years ago, potassium-argon dating, Escorial del Matru within the caldera.[130]

- <7,000 years ago, potassium-argon dating, trachyandesitic lava flow[130] in the western part of the field.[132]

- 6,900 ± 650 years before present, thermoluminescence dating on the Guadalosos cones[127] on an eastward running fracture.[118]

- 4,670 ± 450 years

- 3,700 ± 300 years before present, pumice fallout in and east of the caldera.[118]

- 3,400 ± 300 years before present, trachytic lava flows.[118]

- 2,000 ± 2,000 years ago, surface exposure dating, young looking lava flow in the west.[134]

- 1,705 ± 170 years before present, trachytic volcanic bombs.[118]

- 1,470 ± 120 years before present, thermoluminescence dating on Volcán Santa María[118] although a much older age of 496,000 ± 110,000 years ago has also been given.[55]

- 515 ± 50 years[135] before present, thermoluminescence dating on Morado Sur cone[127] and on the Pampas Negras lapilli field.[118]

- 445 ± 50 years before present, lava domes on the caldera margin.[118]

See also

Explanatory notes

- ^ A coulée is a particular type of lava dome which has flowed sideward like a lava flow.[18]

- electrical conductivity underground.[96]

- ^ Evolved magmas are magmas which due to a settling of crystals have lost part of their magnesium oxide.[102]

- ^ A younger age of 4,860 ± 400 years ago has also been proposed.[118]

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g "Payún Matru". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d Díaz & F 1972, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e Germa et al. 2010, p. 718.

- ^ a b c Blazek & Lourdes 2017, p. 90.

- ^ Díaz & F 1972, p. 24.

- ^ a b c Risso, Németh & Martin 2006, p. 486.

- ^ Inbar & Risso 2001, p. 331.

- ^ ISSN 0306-4565.

- ^ Mikkan 2014, p. 31.

- ^ Risso, Németh & Martin 2006, pp. 485–487.

- ^ a b c Germa et al. 2010, p. 717.

- ^ Espanon et al. 2014, p. 115.

- ^ a b c d Hernando et al. 2019, p. 454.

- ^ a b c d e Díaz & F 1972, p. 15.

- ^ a b Sato et al. 2012, p. 160.

- ^ a b c d e f Burd et al. 2008, p. 91.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Germa et al. 2010, p. 719.

- ISBN 978-3-642-74381-8.

- ^ a b c Díaz & F 1972, p. 16.

- ^ a b Risso, Németh & Martin 2006, p. 487.

- ^ Inbar & Risso 2001b, p. 660.

- ^ Germa et al. 2010, p. 727.

- ^ a b c d e Hernando et al. 2016, p. 152.

- ^ a b Hernando et al. 2019, p. 19.

- ^ a b Rossotti et al. 2008, p. 134.

- ^ a b c Hernando et al. 2014, p. 124.

- ^ a b c d e f g Marchetti, Hynek & Cerling 2014, p. 67.

- ^ Germa et al. 2010, p. 720.

- ^ a b Germa et al. 2010, p. 725.

- ^ a b Mikkan 2017, p. 88.

- ^ Németh et al. 2011, p. 103.

- ^ a b c d e Németh et al. 2011, p. 105.

- ^ Inbar & Risso 2001b, p. 662.

- ^ a b c Espanon et al. 2014, p. 117.

- ^ a b Germa et al. 2010, p. 721.

- ^ Risso, Nemeth & Nullo 2009, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d e f Rossotti et al. 2008, p. 133.

- ^ a b c d e Inbar & Risso 2001, p. 325.

- ^ Hernando et al. 2014, p. 132.

- ^ a b c Mazzarini et al. 2008, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Espanon et al. 2014, p. 116.

- ^ Rossotti et al. 2008, p. 145.

- ^ Hernando et al. 2014, p. 127.

- ^ Hernando et al. 2019, p. 461.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "International Chronostratigraphic Chart" (PDF). International Commission on Stratigraphy. August 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ Blazek & Lourdes 2017, p. 99.

- ^ Blazek & Lourdes 2017, p. 100.

- ^ Mikkan 2017, p. 87.

- ^ Németh et al. 2011, p. 107.

- ^ Németh et al. 2011, pp. 114–115.

- ^ a b c Németh et al. 2011, p. 104.

- ^ Mikkan 2017, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Mikkan 2017, p. 99.

- ^ Risso, Nemeth & Nullo 2009, p. 18.

- ^ a b Risso, Németh & Martin 2006, p. 485.

- ^ Mikkan 2014, p. 43.

- ^ a b Espanon et al. 2014, p. 114.

- ^ a b c Rossotti et al. 2008, p. 132.

- ^ a b Pasquarè, Bistacchi & Mottana 2005, p. 130.

- ^ Rossotti et al. 2008, p. 138.

- ^ Massironi et al. 2007, p. 1.

- ^ Espanon et al. 2014, p. 120.

- ^ Pasquarè, Bistacchi & Mottana 2005, p. 132.

- ^ a b Espanon et al. 2014, p. 125.

- ^ Espanon et al. 2014, p. 128.

- ^ Massironi et al. 2007, p. 2.

- ^ Bernardi et al. 2019, p. 519.

- ^ a b Pasquarè, Bistacchi & Mottana 2005, p. 129.

- ^ Sumino et al. 2019, Fig 1.

- ^ Sumino et al. 2019, p. 4.

- ^ Bernardi et al. 2019, p. 492.

- ^ Díaz & F 1972, p. 18.

- ^ Díaz & F 1972, p. 17.

- ^ a b Díaz & F 1972, p. 19.

- ^ Mazzarini et al. 2008, p. 2.

- ^ a b Pomposiello et al. 2014, p. 813.

- ^ a b c d Burd et al. 2008, p. 90.

- ^ Díaz & F 1972, p. 81.

- ^ Mazzarini et al. 2008, p. 4.

- ^ Díaz & F 1972, p. 82.

- ^ Pomposiello et al. 2014, p. 814.

- ^ Hernando et al. 2014, p. 123.

- ^ Hernando et al. 2019, p. 17.

- ^ Sumino et al. 2019, p. 7.

- ^ Inbar & Risso 2001, p. 323.

- ^ Blazek & Lourdes 2017, p. 88.

- ^ a b Sumino et al. 2019, p. 6.

- ^ Hernando et al. 2016, p. 151.

- ^ Hernando et al. 2014, p. 122.

- ^ Bernardi et al. 2019, p. 496.

- ^ Pomposiello et al. 2014, p. 822.

- ^ Germa et al. 2010, p. 724.

- ^ Hernando et al. 2016, p. 154.

- ^ Germa et al. 2010, pp. 723–724.

- ^ a b Hernando et al. 2016, p. 167.

- OCLC 778681058.

- ^ Burd et al. 2008, p. 93.

- ^ Spakman et al. 2014, p. 211.

- ^ Germa et al. 2010, p. 728.

- ^ Spakman et al. 2014, p. 234.

- ^ Hernando et al. 2016, p. 163.

- ISBN 978-0199653065.

- ^ a b Germa et al. 2010, p. 729.

- ISSN 1475-4754.

- ^ "Payún volcano, Altiplano de Payún Matru, Malargüe Department, Mendoza Province, Argentina". Mindat.org. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Inbar & Risso 2001b, p. 658.

- ^ a b c Mikkan 2014, p. 34.

- ^ Díaz & F 1972, p. 20.

- ^ Inbar & Risso 2001b, p. 659.

- ^ Inbar & Risso 2001, p. 326.

- ^ Díaz & F 1972, p. 22.

- ^ Risso, Nemeth & Nullo 2009, p. 21.

- from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ Inbar & Risso 2001, pp. 324–325.

- ^ a b c Inbar & Risso 2001, p. 324.

- ^ Espanon et al. 2014, p. 126.

- ^ Rossotti et al. 2008, p. 141.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Durán & Mikkan 2009, p. 300.

- ^ a b c Hernando et al. 2016, p. 153.

- ^ Hernando et al. 2019, p. 29.

- ^ a b Spakman et al. 2014, p. 212.

- ^ Durán & Mikkan 2009, p. 301.

- ^ Durán & Mikkan 2009, p. 305.

- ^ Durán & Mikkan 2009, p. 307.

- ISBN 978-0444531179

- from the original on 23 November 2021. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Blazek & Lourdes 2017, p. 102.

- ^ Marchetti, Hynek & Cerling 2014, p. 73.

- ^ a b Mikkan 2017, p. 89.

- ^ a b c d e f Germa et al. 2010, p. 723.

- ^ Sato et al. 2012, p. 166.

- ^ a b c d e Marchetti, Hynek & Cerling 2014, p. 69.

- ISSN 0016-7037.

- ^ Marchetti, Hynek & Cerling 2014, p. 69,73.

- ^ Mikkan 2017, p. 90.

General sources

- Bernardi, Mauro I.; Bertotto, Gustavo W.; Orihashi, Yuji; Sumino, Hirochika; Ponce, Alexis D.; Bernardi, Mauro I.; Bertotto, Gustavo W.; Orihashi, Yuji; Sumino, Hirochika; Ponce, Alexis D. (September 2019). "Volcanología y geocronología de extensos flujos basálticos neógeno cuaternarios del sureste de Payenia, centro-oeste de Argentina" [Volcanology and geochronology of extensive Neogene-Quaternary basaltic lava flows in southeastern Payenia, central-western Argentina]. Andean Geology. 46 (3): 490–525. ISSN 0718-7106.

- Blazek, González; Lourdes, Verónica (1 June 2017). "Evolución morfológica y morfométrica de los conos volcánicos monogenéticos de los campos volcánicos de Payún Matrú, Llancanelo y Cuenca del Río Salado". Boletín de Estudios Geográficos (in Spanish) (107). from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- Burd, Aurora; Booker, John; Pomposiello, Cristina; Favetto, Alicia; Larsen, Jimmy; Giordanengo, Gabriel; Orozco Bernal, Luz (1 January 2008). "Electrical conductivity beneath the Payún Matrú Volcanic Field in the Andean back-arc of Argentina near 36.5°S: Insights into the magma source". Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Andean Geodynamics. Retrieved 20 January 2019 – via ResearchGate.

- Díaz, González; F, Emilio (1972). "Descripción Geológica de la Hoja 30 d, Payún-Matrú" (in Spanish). Servicio Nacional Minero Geológico. Archived from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- Durán, Víctor; Mikkan, Raúl (December 2009). "Impacto del volcanismo holocénico sobre el poblamiento humano del sur de Mendoza (Argentina)" [Impact of Holocene volcanism on human settlement of southern Mendoza (Argentina)]. Intersecciones en Antropología. 10 (2): 295–310. ISSN 1850-373X.

- Espanon, Venera R.; Chivas, Allan R.; Phillips, David; Matchan, Erin L.; Dosseto, Anthony (1 December 2014). "Geochronological, morphometric and geochemical constraints on the Pampas Onduladas long basaltic flow (Payún Matrú Volcanic Field, Mendoza, Argentina)". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 289: 114–129. from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Germa, A.; Quidelleur, X.; Gillot, P. Y.; Tchilinguirian, P. (1 April 2010). "Volcanic evolution of the back-arc Pleistocene Payun Matru volcanic field (Argentina)". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 29 (3): 717–730. ISSN 0895-9811.

- Hernando, I. R.; Franzese, J. R.; Llambías, E. J.; Petrinovic, I. A. (21 May 2014). "Vent distribution in the Quaternary Payún Matrú Volcanic Field, western Argentina: Its relation to tectonics and crustal structures". Tectonophysics. 622: 122–134. ISSN 0040-1951.

- Hernando, I. R.; Petrinovic, I. A.; Gutiérrez, D. A.; Bucher, J.; Fuentes, T. G.; Aragón, E. (15 October 2019). "The caldera-forming eruption of the quaternary Payún Matrú volcano, Andean back-arc of the southern volcanic zone". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 384: 15–30. S2CID 198405888.

- Hernando, Irene Raquel; Petrinovic, Ivan Alejandro; Llambías, Eduardo Jorge; D'Elia, Leandro; González, Pablo Diego; Aragón, Eugenio (1 February 2016). "The role of magma mixing and mafic recharge in the evolution of a back-arc quaternary caldera: The case of Payún Matrú, Western Argentina". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 311: 150–169. from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- Hernando, I. R.; Petrinovic, I. A.; D'Elia, L.; Guzmán, S.; Páez, G. N. (1 March 2019). "Post-caldera pumice cones of the Payún Matrú caldera, Payenia, Argentina: Morphology and deposits characteristics". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 90: 453–462. S2CID 135210762.

- Inbar, M.; Risso, C. (1 January 2001). "A morphological and morphometric analysis of a high density cinder cone volcanic field – Payun Matru, south-central Andes, Argentina". Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie. 45 (3): 321–343. from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- Inbar, Moshe; Risso, Corina (2001b). "Holocene yardangs in volcanic terrains in the southern Andes, Argentina". Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. 26 (6): 657–666. S2CID 55861170.

- Marchetti, David W.; Hynek, Scott A.; Cerling, Thure E. (1 February 2014). "Cosmogenic 3He exposure ages of basalt flows in the northwestern Payún Matru volcanic field, Mendoza Province, Argentina". Quaternary Geochronology. Tracking the pace of Quaternary landscape change with cosmogenic nuclides. 19: 67–75. ISSN 1871-1014.

- Massironi, M; Pasquarè, G; Giacomini, Lorenza; Frigeri, Alessandro; Bistacchi, Andrea; Federico, Costanzo (1 June 2007). The Payun-Matru lava field: a source of analogues for Martian long lava flows (PDF). Exploring Mars and its Earth Analogues. ResearchGate. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- Mazzarini, F.; Fornaciai, A.; Bistacchi, A.; Pasquarè, F. A. (2008). "Fissural volcanism, polygenetic volcanic fields, and crustal thickness in the Payen Volcanic Complex on the central Andes foreland (Mendoza, Argentina)" (PDF). Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 9 (9): n/a. (PDF) from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Mikkan, Raúl (2014). "Payunia, campos volcánicos Llancanelo y Payún Matrú: Patrimonio mundial". Tiempo y Espacio (in Spanish) (33): 31–47. from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- Mikkan, Raúl (22 June 2017). "Morfología compleja y dinámica de los conos monogenéticos Los Morados Sur en el campo volcánico Payún Matrú, Malargüe, Mendoza". Boletín de Estudios Geográficos (in Spanish) (108). from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- Németh, Karoly; Risso, Corina; Nullo, Francisco; Kereszturi, Gabor (2011). "The role of collapsing and cone rafting on eruption style changes and final cone morphology: Los Morados scoria cone, Mendoza, Argentina". Open Geosciences. 3 (2): 102–118. S2CID 129580369.

- Pasquarè, Giorgio; Bistacchi, Andrea; Mottana, Annibale (1 September 2005). "Gigantic individual lava flows in the Andean foothills near Malargüe (Mendoza, Argentina)". Rendiconti Lincei. 16 (3): 127–135. S2CID 126951874.

- Pomposiello, M. C.; Favetto, A.; Mackie, R.; Booker, J. R.; Burd, A. I. (1 August 2014). "Three-dimensional electrical conductivity in the mantle beneath the Payún Matrú Volcanic Field in the Andean backarc of Argentina near 36.5°S: evidence for decapitation of a mantle plume by resurgent upper mantle shear during slab steepening". Geophysical Journal International. 198 (2): 812–827. ISSN 0956-540X.

- Risso, Corina; Németh, Karoly; Martin, Ulrike (1 September 2006). "Geotopvorschläge für pliozäne bis rezente Vulkanfelder in Mendoza, Argentinien" [Proposed geosites on Pliocene to Recent pyroclastic cone fields in Mendoza, Argentina]. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Geowissenschaften. 157 (3): 477–490. .

- Risso, Corina; Nemeth, Karoly; Nullo, Francisco (14 April 2009). Field Guide to Payún Matru and Llancanelo volcanic fields, Malargüe – Mendoza (PDF). 3rd International Maar Conference. ResearchGate. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- Rossotti, Andrea; Massironi, Matteo; Boari, Elena; Bertotto, Gustavo Walter; Francalanci, Lorella; Bistacchi, Andrea; Pasquarè, Giorgio (2008). "Very long pahoehoe inflated basaltic lava flows in the Payenia volcanic province (Mendoza and la Pampa, Argentina)". Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina. 63 (1): 131–149. from the original on 24 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- Sato, Kei; Gonzalez, Pablo D.; Llambias, Eduardo J.; Hernando, Irene R. (5 January 2012). "Volcanic stratigraphy and evidence of magma mixing in the Quaternary Payun Matru volcano, andean backarc in western Argentina". Andean Geology. 39 (1): 158–179. from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- Spakman, W.; González, P. D.; Frei, R.; Aragón, E.; Hernando, I. R. (1 January 2014). "Constraints on the Origin and Evolution of Magmas in the Payún Matrú Volcanic Field, Quaternary Andean Back-arc of Western Argentina". Journal of Petrology. 55 (1): 209–239. ISSN 0022-3530.

- Sumino, Hirochika; Orihashi, Yuji; Ponce, Alexis Daniel; Bertotto, Gustavo Walter; Bernardi, Mauro Ignacio (30 January 2019). "Volcanology and inflation structures of an extensive basaltic lava flow in the Payenia Volcanic Province, extra-Andean back arc of Argentina". Andean Geology. 46 (2): 279–299. from the original on 27 April 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

External links

- Payún Matru Volcanic Field, Argentina: Image of the Day at NASA's Earth Observatory

- Hernando, Irene Raquel (2012). Evolución volcánica y petrológica del volcán Payún Matrú, retroarco andino del sudeste de Mendoza (Doctoral) (in Spanish). hdl:10915/55190.

- Llambías, Eduardo Jorge (1964). Geología y petrografía del volcán Payun Matru (Doctoral). Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales. Universidad de Buenos Aires. .

- Manton, Ryan (2012). The History and Evolution of Payún Matrú Caldera, Mendoza Province, Argentina. Faculty of Science, Medicine & Health – Honours Theses (Bachelor of Science (Honours)). Wollongong, Australia: School of Earth & Environmental Science, University of Wollongong.