Saint George in devotions, traditions and prayers

Saint George is one of Christianity's most popular saints, and is highly honored by both the Western and Eastern Churches.[1] A wide range of devotions, traditions, and prayers to honor the saint have emerged throughout the centuries. He has for long been distinguished by the title of "The Great Martyr" and is one of the most popular saints to be represented in icons.[2] Devotions to Saint George have a large following among Christians, and a large number of churches are dedicated to him worldwide.

Since the Middle Ages, the story of the life of Saint George, both as fact and legend, has come to symbolize the victory of good over evil, and become part of local Christian traditions, festivals and celebrations that continue to date. Saint George has been widely represented in Christian art in multiple media and forms, from paintings and sculptures to stained glass and reliefs, through the ages, and has become the subject of multiple prayers and devotions.[3][4][5][6][7] This article traces the origins, development and growth of the Christian devotions, traditions, and prayers to Saint George.

History and origins

After multiple attempts by hagiographers, the time of Saint George's life was firmly established in the

The saint's father died when he was young, and his mother inherited a large estate which she later descended to her son. He joined the army of the Roman Emperor Diocletian but during the Diocletianic Persecution of Christians declared himself to be one and tore down the Emperor's edict in defiance. Saint George was tortured and dragged behind horses through the streets but would not renounce his Christian beliefs. The saint was then beheaded on April 23, 303. A significant number of conversions to Christianity were reported after his martyrdom which led to his continued veneration.[10][11][12]

But the early devotions to the saint were not limited to the northern countries. In the sixth century Saint George as the Martyr of Cappadocia began to grow in popularity among Greek Egyptians and the devotion spread to other parts of Europe.[16] By the sixth century Saint George had become the ideal Christian knight. In the seventh and eighth centuries stained glass windows in churches across Europe depicted him.[17]

Shrines

The earliest dated Church dedicated to Saint George himself was first mentioned in 518. In Rome, the

It is not known when a church was first built on the site of martyrdom and burial of Saint George. But by the time of the Muslim conquest in the seventh century, a large three-aisled basilica existed, with the martyr's tomb located beneath the main altar.[20]

Saint George was venerated in England as early as the eighth century and devotions to Saint George and shrines dedicated to him continued to grow during the

Many churches were decorated with images of the saint, e.g. St. George's church in

Saint George came to be called on by Christians to aid them in battle and in time of great need, and upon victory churches were built to honor him. Festivals celebrating the ensuing victories became part of local traditions and led to increased devotion to him. He was portrayed in art as a protector and as a symbol of sacrifice, and the interplay of battle cries, prayers, artistic depictions and the construction of Churches in his honor led to increased devotion.[29]

Battles and patronages

The invocation of Saint George as a protector during the Middle Ages is well exemplified by the conduct of the soldiers participating in the

A few days before

Another example is provided by the

During the eleventh century Crusades many of the Normans under Robert Curthose, the Duke of Normandy and son of William the Conqueror, took Saint George as their patron.[34] Pendants bearing the image of Saint George were used for protection. The inscription on an enamel pendant at the British Museum specifically asks the saint to protect the wearer in battle.[2] Songs were composed to Saint George for the English peasantry, e.g.:[35]

As for Saint George O'

Saint George he was a knight, O!

Of all the knights in Christendom,

Saint George is the right, O!

Early patron saints in England were

English

Tales and legends

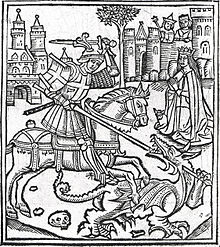

After the thirteenth century, a large portion of the art, iconography and legendary traditions associated with Saint George and many festivals that celebrate him involve the legend of Saint George and the Dragon.

The association of Saint George with the dragon was not attested to until the twelfth century version of Miracula Sancti Georgii (Codex Romanus Angelicus 46, pt. 12, written in Greek).

Some authors have pointed out that many scenes of the legend of Saint George's slaying of the dragon to save the princess correspond to the myth of the slaying of the "sea monster" by Perseus to free Andromeda in Greek mythology. And that the Andromeda episode in the life of Perseus may have helped shape the legend of Saint George and the dragon.[43][44][45] The similarities extend to the visual representations, and many artistic portrayals of Saint George slaying the dragon have distinct counterparts in the renderings of Perseus and Andromeda.[46]

In Russia, the story of Saint George and the Dragon passed through the oral tradition of religious poems (dukhovny stikhi) sung by minstrels and fused the story of the martyrdom of the saint with the Western legend of the liberation of the princess from the dragon.[47]

Images of the life and martyrdom of Saint George and the dragon legend began to appear in churches across Europe, including Sweden, where Saint George was portrayed as the hero and example of all noble young men who needed to be stimulated to show their virtue and bravery in the defense of princesses and in confession of the true belief.

Saint George thus came to be seen as the deliverer of prisoners and protector of the poor, and these sentiments are reflected in art that depicts him. Saint George the Victorious striking down the dragon became one of the most popular subjects in Orthodox icon painting.[49]

Worldwide devotions and statues

By the fifteenth century, the story of the courage of Saint George, and devotions to him, had spread across the world, from the southern parts of India to the northern parts of Russia.

Impressive Saint George statues began to appear across Europe after the fourteenth century.

Saint George first appeared as the patron saint of Russia in 1415 and his popularity in Russia continued to grow. He grew to be so popular in Moscow that 41 churches there were dedicated to him.[53] He is still represented on the coat of arms of the city of Moscow as a knight on a white horse slaying a dragon with a spear. Today, a large number of statues of Saint George can be found in Moscow.[54]

The fifteenth century also witnessed a significant amount of growth in the festivals and patronages for Saint George. As of 1411, San Giorgio's festival on April 24 was a main event in Ferrara, Italy, where he is still the patron saint of the town.[55] Such festivals spread across Europe and became part of local traditions in villages from Turtman, Valais, in Switzerland to Traunstein in Bavaria, Germany.[56]

By the late fifteenth century, as Portuguese ships sailed the seas, symbols of Saint George began to appear in new territories, with

In 1620, as the ship

Devotions and churches dedicated to Saint George continued to spread to other continents.

Due to the

Prayers and novenas

Along with the construction of churches, creation of art and spread of legends, a number of genuine devotions and prayers to Saint George developed over the ages among Christians. These traditions and prayers continue across the world to date, e.g. in May 2008 the arch-priest of

The Prayer to Saint George directly refers to the courage it took for the saint to confess his Christianity before opposing authority:[64]

Almighty God, who gave to your servant George boldness to Confess the Name of our Savior Jesus Christ before the rulers of this world, and courage to die for this faith: Grant that we may always be ready to give a reason for the hope that is in us, and to suffer gladly for the sake of our Lord Jesus Christ; who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever.

The same sentiment is present within the following two Prayers to Saint George:[65]

St. George, Heroic Catholic soldier and defender of your Faith, you dared to criticize a tyrannical Emperor and were subjected to horrible torture. You could have occupied a high military position but you preferred to die for your Lord. Obtain for us the great grace of heroic Christian courage that should mark soldiers of Christ. Amen.

There is also a Prayers of Intercession to Saint George:

Faithful servant of God and invincible martyr, Saint George; favored by God with the gift of faith, and inflamed with an ardent love of Christ, thou didst fight valiantly against the dragon of pride, falsehood, and deceit. Neither pain nor torture, sword nor death could part thee from the love of Christ. I fervently implore thee for the sake of this love to help me by thy intercession to overcome the temptations that surround me, and to bear bravely the trials that oppress me, so that I may patiently carry the cross which is placed upon me; and let neither distress nor difficulties separate me from the love of Our Lord Jesus Christ. Valiant champion of the Faith, assist me in the combat against evil, that I may win the crown promised to them that persevere unto the end.

And:

O GOD, who didst grant to Saint George strength and constancy in the various torments which he sustained for our holy faith; we beseech Thee to preserve, through his intercession, our faith from wavering and doubt, so that we may serve Thee with a sincere heart faithfully unto death. Through Christ our Lord. Amen.

The Novena to Saint George does not have a specific warrior context, but simply asks God for divine assistance and the imitation of the life of the saint:[66]

Almighty and eternal God! With lively faith and reverently worshiping Thy divine Majesty, I prostrate myself before Thee and invoke with filial trust Thy supreme bounty and mercy. Illumine the darkness of my intellect with a ray of Thy heavenly light and inflame my heart with the fire of Thy divine love that I may contemplate the great virtues and merits of the Saint in whose honor I make this novena, and following his example imitate, like him, the life of Thy Divine Son.

Gallery of art and architecture

Paintings and statues

Paintings

-

German Altarpiece panel, 1470

-

Rogier van der Weyden, 15th century

-

Raphael, 1505-1506

-

Tintoretto, 16th century

-

Raphael 16th century

-

Franz Pforr, 1811

-

Gustave Moreau, mid-late 19th century

-

August Macke, 1912

-

The Torture of St. George,Michael Coxcie, c. 1580

-

St. George Dragged by Horses, byBernardo Martorell, 15th century

-

The Beheading of St. George,St. George's Oratory, Padua, Italy

-

The Martyrdom of St. George, by Paolo Veronese, 1564.

Icons

-

St. George with theTheodoreand angels, late 6th century

-

Conquering Saints George andTheodore on horses, Saint Catherine's Monastery, 9th or 10th century

-

St. George and scenes of his life. Saint Catherine's Monastery, 13th century

-

Russian icon, 15th century

-

16th-century Russian icon

-

Byzantine Greek icon

-

17th-century Greek icon

Statues

Churches and altars

Churches

-

St. George's Church,Roman Catholic)

-

Indian Orthodox)

Altars

-

San Giorgio Church, Bormida, Liguria, Italy

See also

References

- ISBN 978-1-57607-089-5page 408

- ^ ISBN 0-674-02619-5page 69

- ISBN 0-495-41060-8page 546

- ISBN 0-7099-1006-1page 84

- ISBN 0-691-01175-3page 115

- ISBN 1-4375-2015-4, page 67

- ISBN 0-7614-2059-2page 117

- ISBN 1-84014-694-Xpage 110

- ^ Bibliotheca Hagiographica Graeca 271, 272.

- ISBN 1-59605-452-2page 87

- ^ John Foxe, History of Christian martyrdom, Published by J.P. Peaslee, 1834 page 57

- ^ Alban Butler, The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Other Principal Saints Published by Duffy, 1845, page 235

- ISBN 0-521-81955-5page 141

- ISBN 1-59605-452-2page 556

- ISBN 0-271-01628-0page 119

- ISBN 0-415-24253-3, page 276

- ISBN 0-8294-0505-4page 110

- ISBN 90-04-09691-4page 345

- ISBN 0-7100-0098-7page 278

- ISBN 0-521-39037-0page 25

- ISBN 0-87973-910-Xpage 568

- ISBN 0-19-815896-3, page 274

- ^ C. J. Wells, German, a linguistic history to 1945 Oxford University Press, 1985

ISBN 0-19-815795-9page 48

- ISBN 0-8078-4389-Xpage 142

- ISBN 0-521-41411-3page 227

- ^ Frank Sayers, Collective Works Published by Matchett and Stevenson, 1808 page 126

- ISBN 1-934536-03-2page 176

- ISBN 0-226-14291-4page 47

- ISBN 1-57607-089-1page 410

- ISBN 0-85115-944-3page 137

- ISBN 0-7546-1516-2page 21

- ISBN 0-271-02551-4page 102

- ISBN 0-271-01628-0page 68

- ISBN 1-884964-49-4, page 105

- ^ James Dixon, 1857, Ancient Poems, Ballads and Songs of the Peasantry of England, Published by J.W. Parker, page 168.

- ISBN 0-415-03345-4, page 75

- ISBN 0-7614-0308-6, page 44

- ISBN 1-57607-355-6page 303

- ISBN 0-299-05584-1page 216

- ISBN 0-415-42725-8page 136

- ISBN 978-0-691-00153-1page 238

- ISBN 0-313-32810-2, page 122

- ISBN 0-8196-0285-Xpage 516

- ^ Northrop Frye, Biblical and classical myths University of Toronto Press, 2004

ISBN 0-8020-8695-0, page 85

- ISBN 1-60506-431-9page 120

- ISBN 2-913621-06-6page 310

- ISBN 0-8371-8294-8page 99

- ISBN 90-232-3377-8page 116

- ISBN 978-0-913836-99-6page 137

- ISBN 0-19-513028-6, page 40

- ^ Kerala Tourism website

- ISBN 0-300-12189-Xpage 135

- ISBN 978-1-57607-130-4page 90

- ^ Richard Hare, 1965, The Art and Artists of Russia, Taylor and Francis Press, page 77

- ISBN 0-19-537827-Xpage 26

- ISBN 1-4375-2015-4, page 218

- ISBN 0-8018-5955-7page 2

- ISBN 0-226-70941-8page 123

- ISBN 0-439-09941-2page 36

- ^ http://www.etgstores.com/bookcafe/stgeorgeday.html The International Year of the Book: St. George Day on Staten Island 2011

- ^ ISBN 9781351722179.

- ^ Saint George's Basilica News

- ^ Saint Mary's Cathedral Archived 2009-05-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Prayer to Saint George". www.catholic-saints.info. Retrieved 2020-08-21.

- ^ "St. George Medal". st-george-medal.com. Retrieved 2020-08-21.

- ISBN 1-84753-978-5page 579