William the Conqueror

| William the Conqueror | |

|---|---|

King of England | |

| Reign | 25 December 1066 – 9 September 1087 |

| Coronation | 25 December 1066 |

| Predecessor |

|

| Successor | Saint-Étienne de Caen, Normandy |

| Spouse | Matilda of Flanders (m. 1051/2; d. 1083) |

| Issue Detail |

|

Herleva of Falaise | |

William the Conqueror

William was the son of the unmarried Duke

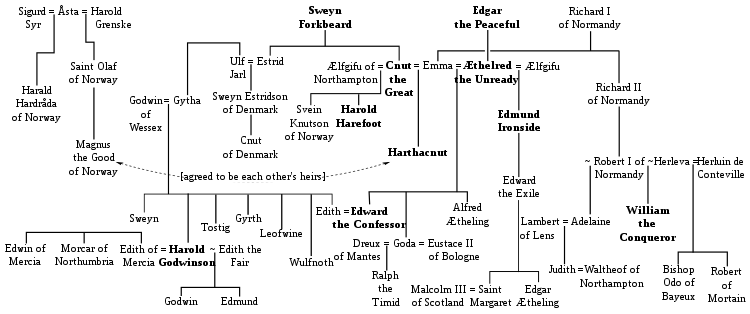

In the 1050s and early 1060s, William became a contender for the throne of England held by the childless Edward the Confessor, his first cousin once removed. There were other potential claimants, including the powerful English earl Harold Godwinson, whom Edward named as king on his deathbed in January 1066. Arguing that Edward had previously promised the throne to him and that Harold had sworn to support his claim, William built a large fleet and invaded England in September 1066. He decisively defeated and killed Harold at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October 1066. After further military efforts, William was crowned king on Christmas Day, 1066, in London. He made arrangements for the governance of England in early 1067 before returning to Normandy. Several unsuccessful rebellions followed, but William's hold on England was mostly secure by 1075, allowing him to spend the greater part of his reign in continental Europe.

William's final years were marked by difficulties in his continental domains, troubles with his son, Robert, and threatened invasions of England by the

Background

Danish raids on England continued, and Æthelred sought help from Richard, taking refuge in Normandy in 1013 when King

After Cnut's death in 1035, the English throne fell to

Early life

William was born in 1027 or 1028 at

Robert I succeeded his elder brother

Robert may have been briefly betrothed to a daughter of King Cnut, but no marriage took place. It is unclear whether William would have been supplanted in the ducal succession if Robert had had a legitimate son. Earlier dukes had been

Duke of Normandy

Challenges

William faced several challenges on becoming duke, including his illegitimate birth and his youth: he was either seven or eight years old.[17][18][h] He enjoyed the support of his great-uncle, Archbishop Robert, as well as King Henry I of France, enabling him to succeed to his father's duchy.[21] The support given to the exiled English princes in their attempt to return to England in 1036 shows that the new duke's guardians were attempting to continue his father's policies,[2] but Archbishop Robert's death in March 1037 removed one of William's main supporters, and Normandy quickly descended into chaos.[21]

The anarchy in the duchy lasted until 1047,

King Henry continued to support the young duke,[27] but in late 1046 opponents of William came together in a rebellion centred in lower Normandy, led by Guy of Burgundy with support from Nigel, Viscount of the Cotentin, and Ranulf, Viscount of the Bessin. According to stories that may have legendary elements, an attempt was made to seize William at Valognes, but he escaped under cover of darkness, seeking refuge with King Henry.[28] In early 1047 Henry and William returned to Normandy and were victorious at the Battle of Val-ès-Dunes near Caen, although few details of the fighting are recorded.[29] William of Poitiers claimed that the battle was won mainly through William's efforts, but earlier accounts claim that King Henry's men and leadership also played an important part.[2] William assumed power in Normandy, and shortly after the battle promulgated the Truce of God throughout his duchy, in an effort to limit warfare and violence by restricting the days of the year on which fighting was permitted.[30] Although the Battle of Val-ès-Dunes marked a turning point in William's control of the duchy, it was not the end of his struggle to gain the upper hand over the nobility. The period from 1047 to 1054 saw almost continuous warfare, with lesser crises continuing until 1060.[31]

Consolidation of power

William's next efforts were against Guy of Burgundy, who retreated to his castle at

On the death of Hugh of Maine, Geoffrey Martel occupied Maine in a move contested by William and King Henry; eventually, they succeeded in driving Geoffrey from the county, and in the process, William secured the Bellême family strongholds at Alençon and Domfront for himself. He was thus able to assert his overlordship over the Bellême family and compel them to act consistently with Norman interests.[35] However, in 1052 the king and Geoffrey Martel made common cause against William as some Norman nobles began to contest William's increasing power. Henry's about-face was probably motivated by a desire to retain dominance over Normandy, which was now threatened by William's growing mastery of his duchy.[36] William was engaged in military actions against his own nobles throughout 1053,[37] as well as with the new Archbishop of Rouen, Mauger.[38]

In February 1054 the king and the Norman rebels launched a double invasion of the duchy. Henry led the main thrust through the

One factor in William's favour was his marriage to

Appearance and character

No authentic portrait of William has been found; the contemporary depictions of him on the Bayeux Tapestry and on his seals and coins are conventional representations designed to assert his authority.[50] There are some written descriptions of a burly and robust appearance, with a guttural voice. He enjoyed excellent health until old age, although he became quite fat in later life.[51] He was strong enough to draw bows that others were unable to pull and had great stamina.[50] Geoffrey Martel described him as without equal as a fighter and horseman.[52] Examination of William's femur, the only bone to survive when the rest of his remains were destroyed, showed he was approximately 5 feet 10 inches (1.78 m) tall.[50]

There are records of two tutors for William during the late 1030s and early 1040s, but the extent of his literary education is unclear. He was not known as a patron of authors, and there is little evidence that he sponsored scholarships or intellectual activities.[2] Orderic Vitalis records that William tried to learn to read Old English late in life, but he was unable to devote sufficient time to the effort and quickly gave up.[53] William's main hobby appears to have been hunting. His marriage to Matilda appears to have been quite affectionate, and there are no signs that he was unfaithful to her – unusual in a medieval monarch. Medieval writers criticised William for his greed and cruelty, but his personal piety was universally praised by contemporaries.[2]

Norman administration

Norman government under William was similar to the government that had existed under earlier dukes. It was a fairly simple administrative system, built around the ducal household,[54] a group of officers including stewards, butlers, and marshals.[55] The duke travelled constantly around the duchy, confirming charters and collecting revenues.[56] Most of the income came from the ducal lands, as well as from tolls and a few taxes. This income was collected by the chamber, one of the household departments.[55]

William cultivated close relations with the church in his duchy. He took part in church councils and made several appointments to the Norman episcopate, including the appointment of

English and continental concerns

In 1051 the childless King Edward of England appears to have chosen William as his successor.[59] William was the grandson of Edward's maternal uncle, Richard II of Normandy.[59]

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, in the "D" version, states that William visited England in the later part of 1051, perhaps to secure confirmation of the succession,[60] or perhaps to secure aid for his troubles in Normandy.[61] The trip is unlikely given William's absorption in warfare with Anjou at the time. Whatever Edward's wishes, it was likely that any claim by William would be opposed by Godwin, Earl of Wessex, a member of the most powerful family in England.[60] Edward had married Edith, Godwin's daughter, in 1043, and Godwin appears to have been one of the main supporters of Edward's claim to the throne.[62] By 1050, however, relations between the king and the earl had soured, culminating in a crisis in 1051 that led to the exile of Godwin and his family from England. During this exile, Edward offered the throne to William.[63] Godwin returned from exile in 1052 with armed forces, and a settlement was reached between the king and the earl, restoring the earl and his family to their lands and replacing Robert of Jumièges, a Norman whom Edward had named Archbishop of Canterbury, with Stigand, the Bishop of Winchester.[64] No English source mentions a supposed embassy by Archbishop Robert to William conveying the promise of the succession, and the two Norman sources that mention it, William of Jumièges and William of Poitiers, are not precise in their chronology of when this visit took place.[61]

Count

Earl Godwin died in 1053.

In 1065

Invasion of England

Harold's preparations

Harold was crowned on 6 January 1066 in Edward's new

Harold's brother Tostig made probing attacks along the southern coast of England in May 1066, landing at the Isle of Wight using a fleet supplied by Baldwin of Flanders. Tostig appears to have received little local support, and further raids into Lincolnshire and near the Humber met with no more success, so he retreated to Scotland. According to the Norman writer William of Jumièges, William had meanwhile sent an embassy to King Harold Godwinson to remind Harold of his oath to support William's claim, although whether this embassy actually occurred is unclear. Harold assembled an army and a fleet to repel William's anticipated invasion force, deploying troops and ships along the English Channel for most of the summer.[74]

William's preparations

William of Poitiers describes a council called by Duke William, in which the writer gives an account of a debate between William's nobles and supporters over whether to risk an invasion of England. Although some sort of formal assembly probably was held, it is unlikely that any debate took place: the duke had by then established control over his nobles, and most of those assembled would have been anxious to secure their share of the rewards from the conquest of England.[79] William of Poitiers also relates that the duke obtained the consent of Pope Alexander II for the invasion, along with a papal banner. The chronicler also claimed that the duke secured the support of Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor, and King Sweyn II of Denmark. Henry was still a minor, however, and Sweyn was more likely to support Harold, who could then help Sweyn against the Norwegian king, so these claims should be treated with caution. Although Alexander gave papal approval to the conquest after it succeeded, no other source claims papal support prior to the invasion.[n][80] Events after the invasion, which included the penance William performed and statements by later popes, lend circumstantial support to the claim of papal approval. To deal with Norman affairs, William put the government of Normandy into the hands of his wife for the duration of the invasion.[2]

Throughout the summer, William assembled an army and an invasion fleet in Normandy. Although William of Jumièges's claim that the ducal fleet numbered 3,000 ships is clearly an exaggeration, it was probably large and mostly built from scratch. Although William of Poitiers and William of Jumièges disagree about where the fleet was built – Poitiers states it was constructed at the mouth of the

Tostig and Hardrada's invasion

Tostig Godwinson and Harald Hardrada invaded

Battle of Hastings

After defeating Harald Hardrada and Tostig, Harold left much of his army in the north, including Morcar and Edwin, and marched the rest south to deal with the threatened Norman invasion.[81] He probably learned of William's landing while he was travelling south. Harold stopped in London for about a week before marching to Hastings, so it is likely that he spent about a week on his march south, averaging about 27 miles (43 kilometres) per day,[82] for the distance of approximately 200 miles (320 kilometres).[83] Although Harold attempted to surprise the Normans, William's scouts reported the English arrival to the duke. The exact events preceding the battle are obscure, with contradictory accounts in the sources, but all agree that William led his army from his castle and advanced towards the enemy.[84] Harold had taken a defensive position at the top of Senlac Hill (present-day Battle, East Sussex), about 6 miles (9.7 kilometres) from William's castle at Hastings.[85]

The battle began at about 9 am on 14 October and lasted all day. While a broad outline is known, the exact events are obscured by contradictory accounts.

Harold's body was identified the day after the battle, either through his armour or marks on his body. The English dead, including some of

March on London

William may have hoped the English would surrender following his victory, but they did not. Instead, some of the English clergy and magnates nominated Edgar the Ætheling as king, though their support for Edgar was only lukewarm. After waiting a short while, William secured

Consolidation

First actions

William remained in England after his coronation and tried to reconcile the native magnates. The remaining earls – Edwin (of Mercia), Morcar (of Northumbria), and

While William was in Normandy, a former ally, Eustace, the Count of Boulogne, invaded at Dover but was repulsed. English resistance had also begun, with Eadric the Wild attacking Hereford and revolts at Exeter, where Harold's mother Gytha was a focus of resistance.[98] FitzOsbern and Odo found it difficult to control the native population and undertook a programme of castle-building to maintain their hold on the kingdom.[2] William returned to England in December 1067 and marched on Exeter, which he besieged. The town held out for 18 days. After it fell to William he built a castle to secure his control. Harold's sons were meanwhile raiding the southwest of England from a base in Ireland. Their forces landed near Bristol but were defeated by Eadnoth. By Easter, William was at Winchester, where he was soon joined by his wife Matilda, who was crowned in May 1068.[98]

English resistance

In 1068 Edwin and Morcar rose in revolt, supported by Gospatric, Earl of Northumbria. Orderic Vitalis states that Edwin's reason for revolting was that the proposed marriage between himself and one of William's daughters had not taken place, but another reason probably included the increasing power of fitzOsbern in Herefordshire, which affected Edwin's power within his own earldom. The king marched through Edwin's lands and built Warwick Castle. Edwin and Morcar submitted, but William continued on to York, building York and Nottingham Castles before returning south. On his southbound journey, he began constructing Lincoln, Huntingdon, and Cambridge Castles. William placed supporters in charge of these new fortifications – among them William Peverel at Nottingham and Henry de Beaumont at Warwick – then returned to Normandy late in 1068.[98]

Early in 1069, Edgar the Ætheling revolted and attacked York. Although William returned to York and built another castle, Edgar remained free, and in the autumn he joined up with King Sweyn.

Church affairs

While at Winchester in 1070, William met with three

Troubles in England and on the Continent

Danish raids and rebellion

Although Sweyn had promised to leave England, he returned in early 1070, raiding along the Humber and East Anglia toward the

In 1071 William defeated the last rebellion of the north. Earl Edwin was betrayed by his own men and killed, while William built a causeway to subdue the Isle of Ely, where Hereward the Wake and Morcar were hiding. Hereward escaped, but Morcar was captured, deprived of his earldom, and imprisoned. In 1072 William invaded Scotland, defeating Malcolm, who had recently invaded the north of England. William and Malcolm agreed to peace by signing the

William returned to England to release his army from service in 1073 but quickly returned to Normandy, where he spent all of 1074.

Revolt of the Earls

In 1075, during William's absence,

The exact reason for the rebellion is unclear. It was launched at the wedding of Ralph to a relative of Roger, held at Exning in Suffolk. Waltheof, the earl of Northumbria, although one of William's favourites, was involved, and some Breton lords were ready to rebel in support of Ralph and Roger. Ralph also requested Danish aid. William remained in Normandy while his men in England subdued the revolt. Roger was unable to leave his stronghold in Herefordshire because of efforts by Wulfstan, the Bishop of Worcester, and Æthelwig, the Abbot of Evesham. Ralph was bottled up in Norwich Castle by the combined efforts of Odo of Bayeux, Geoffrey de Montbray, Richard fitzGilbert, and William de Warenne. Ralph eventually left Norwich in the control of his wife and left England, ending up in Brittany. Norwich was besieged and surrendered, with the garrison allowed to go to Brittany. Meanwhile, the Danish king's brother, Cnut, had finally arrived in England with a fleet of 200 ships, but Norwich had already surrendered. The Danes raided along the coast before returning home.[110] William returned to England later in 1075 to deal with the Danish threat, leaving his wife Matilda in charge of Normandy. He celebrated Christmas at Winchester and dealt with the aftermath of the rebellion.[115] Roger and Waltheof were kept in prison, where Waltheof was executed in May 1076. Before this, William had returned to the continent, where Ralph had continued the rebellion from Brittany.[110]

Troubles at home and abroad

Earl Ralph had secured control of the castle at

In late 1077 or early 1078 trouble began between William and his eldest son, Robert. Although Orderic Vitalis describes it as starting with a quarrel between Robert and his younger brothers

Word of William's defeat at Gerberoi stirred up difficulties in northern England. In August and September 1079 King Malcolm of Scots raided south of the River Tweed, devastating the land between the River Tees and the Tweed in a raid that lasted almost a month. The lack of Norman response appears to have caused the Northumbrians to grow restive, and in the spring of 1080 they rebelled against the rule of Walcher, the Bishop of Durham and Earl of Northumbria. Walcher was killed on 14 May 1080, and the king dispatched his half-brother Odo to deal with the rebellion.[120] William departed Normandy in July 1080,[121] and in the autumn his son Robert was sent on a campaign against the Scots. Robert raided into Lothian and forced Malcolm to agree to terms, building the 'new castle' at Newcastle upon Tyne while returning to England.[120] The king was at Gloucester for Christmas 1080 and at Winchester for Whitsun in 1081, ceremonially wearing his crown on both occasions. A papal embassy arrived in England during this period, asking that William do fealty for England to the papacy, a request that he rejected.[121] William also visited Wales in 1081, although the English and the Welsh sources differ on the purpose of the visit. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle states that it was a military campaign, but Welsh sources record it as a pilgrimage to St Davids in honour of Saint David. William's biographer David Bates argues that the former explanation is more likely: the balance of power had recently shifted in Wales and William would have wished to take advantage of this to extend Norman power. By the end of 1081, William was back on the continent, dealing with disturbances in Maine. Although he led an expedition into Maine, the result was instead a negotiated settlement arranged by a papal legate.[122]

Last years

Sources for William's actions between 1082 and 1084 are meagre. According to the historian David Bates, this probably means that little of note happened, and that because William was on the continent, there was nothing for the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to record.[123] In 1082, William ordered the arrest of his half-brother Odo. The exact reasons are unclear, as no contemporary author recorded what caused the quarrel between the half-brothers. Orderic Vitalis later recorded that Odo had aspirations to become pope and that Odo had attempted to persuade some of William's vassals to join Odo in an invasion of southern Italy. This would have been considered tampering with the king's authority over his vassals, which William would not have tolerated. Although Odo remained in confinement for the rest of William's reign, his lands were not confiscated. In 1083, William's son Robert rebelled once more with support from the French king. A further blow was the death of Queen Matilda on 2 November 1083. William was always described as close to his wife, and her death would have added to his problems.[124]

Maine continued to be difficult, with a rebellion by

William as king

Changes in England

As part of his efforts to secure England, William ordered many castles,

At first, most of the newly settled Normans kept household knights and did not settle their retainers with fiefs of their own, but gradually these household knights came to be granted lands of their own, a process known as subinfeudation. William also required his newly created magnates to contribute fixed quotas of knights towards not only military campaigns but also castle garrisons. This method of organising the military forces was a departure from the pre-Conquest English practice of basing military service on territorial units such as the hide.[128]

By William's death, after weathering a series of rebellions, most of the native Anglo-Saxon aristocracy had been replaced by Norman and other continental magnates. Not all of the Normans who accompanied William in the initial conquest acquired large amounts of land in England. Some appear to have been reluctant to take up lands in a kingdom that did not always appear pacified. Although some of the newly rich Normans in England came from William's close family or from the upper Norman nobility, others were from relatively humble backgrounds.[129] William granted some lands to his continental followers from the holdings of one or more specific Englishmen; at other times, he granted a compact grouping of lands previously held by many different Englishmen to one Norman follower, often to allow for the consolidation of lands around a strategically placed castle.[130]

The medieval chronicler William of Malmesbury says that the king also seized and depopulated many miles of land (36 parishes), turning it into the royal New Forest to support his enthusiastic enjoyment of hunting. Modern historians have concluded that the New Forest depopulation was greatly exaggerated. Most of the New Forest comprises poor agricultural lands, and archaeological and geographic studies have shown that it was likely sparsely settled when it was turned into a royal forest.[131] William was known for his love of hunting, and he introduced the forest law into areas of the country, regulating who could hunt and what could be hunted.[132]

Administration

After 1066, William did not attempt to integrate his separate domains into one unified realm with one set of laws. His seal from after 1066, of which six impressions still survive, was made for him after he conquered England and stressed his role as king, while separately mentioning his role as duke.[t] When in Normandy, William acknowledged that he owed fealty to the French king, but in England no such acknowledgement was made – further evidence that the various parts of William's lands were considered separate. The administrative machinery of Normandy, England, and Maine continued to exist separate from the other lands, with each one retaining its own forms. For example, England continued the use of writs, which were not known on the continent. Also, the charters and documents produced for the government in Normandy differed in formulas from those produced in England.[133]

William took over an English government that was more complex than the Norman system. England was divided into

William continued the collection of

Besides taxation, William's large landholdings throughout England strengthened his rule. As King Edward's heir, he controlled all of the former royal lands. He also retained control of much of the lands of Harold and his family, which made the king the largest secular landowner in England by a wide margin.[v]

Domesday Book

At Christmas 1085, William ordered the compilation of a survey of the landholdings held by himself and by his vassals throughout his kingdom, organised by counties. It resulted in a work now known as the Domesday Book. The listing for each county gives the holdings of each landholder, grouped by owners. The listings describe the holding, who owned the land before the Conquest, its value, its tax assessment, and usually the number of peasants, ploughs, and any other resources the holding had. Towns were listed separately. All the English counties south of the River Tees and River Ribble are included. The whole work seems to have been mostly completed by 1 August 1086, when the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that William received the results and that all the chief magnates swore the Salisbury Oath, a renewal of their oaths of allegiance.[138] William's motivation in ordering the survey is unclear, but it probably had several purposes, such as making a record of feudal obligations and justifying increased taxation.[2]

Death and aftermath

William left England towards the end of 1086. Following his arrival back on the continent he married his daughter

William left Normandy to Robert, and the custody of England was given to William's second surviving son, also called William, on the assumption that he would become king. The youngest son, Henry, received money. After entrusting England to his second son, the elder William sent the younger William back to England on 7 or 8 September, bearing a letter to Lanfranc ordering the archbishop to aid the new king. Other bequests included gifts to the Church and money to be distributed to the poor. William also ordered that all of his prisoners be released, including his half-brother Odo.[139]

Disorder followed William's death; everyone who had been at his deathbed left the body at Rouen and hurried off to attend to their own affairs. Eventually, the clergy of Rouen arranged to have the body sent to Caen, where William had desired to be buried in his foundation of the

William's grave is marked by a marble slab with a Latin inscription dating from the early 19th century. The tomb has been disturbed several times since 1087, the first time in 1522 when the grave was opened on orders from the papacy. The intact body was restored to the tomb at that time, but in 1562, during the French Wars of Religion, the grave was reopened and the bones scattered and lost, with the exception of one thigh bone. This lone relic was reburied in 1642 with a new marker, which was replaced 100 years later with a more elaborate monument. This tomb was again destroyed during the French Revolution but was eventually replaced with the current ledger stone.[141][w]

Legacy

The immediate consequence of William's death was a war between his sons Robert and William over control of England and Normandy.[2] Even after the younger William's death in 1100 and the succession of his youngest brother Henry as king, Normandy and England remained contested between the brothers until Robert's capture by Henry at the Battle of Tinchebray in 1106. The difficulties over the succession led to a loss of authority in Normandy, with the aristocracy regaining much of the power they had lost to the elder William. His sons also lost much of their control over Maine, which revolted in 1089 and managed to remain mostly free of Norman influence thereafter.[143]

The impact on England of William's conquest was profound; changes in the Church, aristocracy, culture, and language of the country have persisted into modern times. The Conquest brought the kingdom into closer contact with France and forged ties that lasted throughout the Middle Ages. Another consequence of William's invasion was the sundering of the formerly close ties between England and Scandinavia. William's government blended elements of the English and Norman systems into a new one that laid the foundations of the later medieval English kingdom.

William's reign has caused historical controversy since before his death. William of Poitiers wrote glowingly of William's reign and its benefits, but the obituary notice for William in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle condemns William in harsh terms.

Family and children

William and his wife Matilda had at least nine children.[49] The birth order of the sons is clear, but no source gives the relative order of birth of the daughters.[2]

- Sybilla, daughter of Geoffrey, Count of Conversano.[148]

- Richard was born before 1056, died around 1075.[49]

- William was born between 1056 and 1060, died on 2 August 1100.[49] King of England, killed in the New Forest.[149]

- Henry was born in late 1068, and died on 1 December 1135.[49] King of England, married Edith, daughter of Malcolm III of Scotland. His second wife was Adeliza of Louvain.[150]

- Cecilia (or Cecily) was born before 1066, died 1127, Abbess of Holy Trinity, Caen.[49]

- Matilda[2][151] was born around 1061, died perhaps about 1086.[150] Mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086 as a daughter of William.[49]

- Constance died 1090, married Alan IV, Duke of Brittany.[49]

- Adela died 1137, married Stephen, Count of Blois.[49]

- (Possibly) Agatha, the betrothed of Alfonso VI of León and Castile.[x]

There is no evidence of any illegitimate children born to William.[155]

Notes

- Old English: Willelm

- ^ He was regularly described as bastardus (bastard) in non-Norman contemporary sources.[2]

- ^ Although the chronicler William of Poitiers claimed that Edward's succession was due to Duke William's efforts, this is highly unlikely, as William was at that time practically powerless in his own duchy.[2]

- ^ The exact date of William's birth is confused by contradictory statements by the Norman chroniclers. Orderic Vitalis has William on his deathbed claim that he was 64 years old, which would place his birth around 1023. But elsewhere, Orderic states that William was 8 years old when his father left for Jerusalem in 1035, placing the year of birth in 1027. William of Malmesbury gives an age of 7 for William when his father left, giving 1028. Another source, De obitu Willelmi, states that William was 59 years old when he died in 1087, allowing for either 1027 or 1028.[10]

- ^ This made Emma of Normandy his great-aunt and Edward the Confessor his cousin.[11][12]

- La Ferté-Macé.[10]

- ^ Walter had two daughters. One became a nun, and the other, Matilda, married Ralph Tesson.[10]

- Gregorian reform, held the view that the sin of extramarital sex tainted any offspring that resulted, but nobles had not totally embraced the Church's viewpoint during William's lifetime.[19] By 1135 the illegitimate birth of Robert of Gloucester, son of William's son Henry I of England, was enough to bar Robert's succession as king when Henry died without legitimate male heirs, even though he had some support from the English nobility.[20]

- ^ The reasons for the prohibition are not clear. There is no record of the reason from the Council, and the main evidence is from Orderic Vitalis. He hinted obliquely that William and Matilda were too closely related, but gave no details, hence the matter remains obscure.[43]

- ^ The exact date of the marriage is unknown, but it was probably in 1051 or 1052, and certainly before the end of 1053, as Matilda is named as William's wife in a charter dated in the later part of that year.[45]

- Abbaye aux Dames (or Sainte Trinité) for women which was founded by Matilda around four years later.[48]

- ^ Ætheling means "prince of the royal house" and usually denoted a son or brother of a ruling king.[71]

- ^ Edgar the Ætheling was another claimant,[75] but Edgar was young,[76] likely only 14 in 1066.[77]

- ^ The Bayeux Tapestry may depict a papal banner carried by William's forces, but this is not named as such in the tapestry.[80]

- ^ William of Malmesbury states that William did accept Gytha's offer, but William of Poitiers states that William refused the offer.[90] Modern biographers of Harold agree that William refused the offer.[91][92]

- ^ Medieval chroniclers frequently referred to 11th-century events only by the season, making more precise dating impossible.

- ^ The historian Frank Barlow points out that William had suffered from his uncle Mauger's ambitions while young and thus would not have countenanced creating another such situation.[102]

- ^ Edgar remained at William's court until 1086 when he went to the Norman principality in southern Italy.[108]

- ^ Although Simon was a supporter of William, the Vexin was actually under the overlordship of King Philip, which is why Philip secured control of the county when Simon became a monk.[116]

- ^ The seal shows a mounted knight and is the first extant example of an equestrian seal.[133]

- ^ Between 1066 and 1072, William spent only 15 months in Normandy and the rest in England. After returning to Normandy in 1072, he spent around 130 months in Normandy as against about 40 months in England.[134]

- Roger of Montgomery, the third-largest landowner.[137]

- E. A. Freeman was of the opinion that the bone had been lost in 1793.[142]

- Alfonso VI of León and Robert Guiscard, while William of Malmesbury and Orderic Vitalis both show a daughter of William to have been betrothed to Alfonso "king of Galicia" but to have died before the marriage. In his Historia Ecclesiastica, Orderic specifically names her as Agatha, "former fiancee of Harold".[152][153] This conflicts with Orderic's own earlier additions to the Gesta Normannorum Ducum, where he instead named Harold's fiance as William's daughter, Adelidis.[151] Recent accounts of the complex marital history of Alfonso VI have accepted that he was betrothed to a daughter of William named Agatha,[152][153][154] while Douglas dismisses Agatha as a confused reference to known daughter Adeliza.[49] Elisabeth van Houts is non-committal, being open to the possibility that Adeliza was engaged before becoming a nun, but also accepting that Agatha may have been a distinct daughter of William.[151]

Citations

- ^ a b c d Bates William the Conqueror p. 33

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Bates "William I" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ Potts "Normandy, 911–1144" p. 31

- ^ Collins Early Medieval Europe pp. 376–377

- ^ Williams Æthelred the Unready pp. 42–43

- ^ Williams Æthelred the Unready pp. 54–55

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest pp. 80–83

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest pp. 83–85

- ^ "William the Conqueror" Royal Family

- ^ a b c d e Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 379–382

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror p. 417

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror p. 420

- ^ van Houts "Les femmes" Tabularia "Études" pp. 19–34

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 31–32

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 32–34, 145

- ^ a b Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 35–37

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror p. 36

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror p. 37

- ^ Crouch Birth of Nobility pp. 132–133

- ^ Given-Wilson and Curteis Royal Bastards p. 42

- ^ a b Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 38–39

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror p. 51

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror p. 40

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror p. 37

- ^ Searle Predatory Kinship pp. 196–198

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 42–43

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 45–46

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 47–49

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror p. 38

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror p. 40

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror p. 53

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 54–55

- ^ a b Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 56–58

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror pp. 43–44

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 59–60

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 63–64

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 66–67

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror p. 64

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror p. 67

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 68–69

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 75–76

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror p. 50

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 391–393

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror p. 76

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror p. 391

- ^ a b Bates William the Conqueror pp. 44–45

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror p. 80

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror pp. 66–67

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 393–395

- ^ a b c Bates William the Conqueror pp. 115–116

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 368–369

- ^ Searle Predatory Kinship p. 203

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest p. 323

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror p. 133

- ^ a b c Bates William the Conqueror pp. 23–24

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror pp. 63–65

- ^ a b Bates William the Conqueror pp. 64–66

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 111–112

- ^ a b Barlow "Edward" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ a b Bates William the Conqueror pp. 46–47

- ^ a b Huscroft Norman Conquest pp. 93–95

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest pp. 86–87

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest pp. 89–91

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest pp. 95–96

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror p. 174

- ^ a b Bates William the Conqueror p. 53

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 178–179

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest pp. 98–100

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest pp. 102–103

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest p. 97

- ^ Miller "Ætheling" Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England pp. 13–14

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest pp. 107–109

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest pp. 115–116

- ^ a b c Huscroft Ruling England pp. 12–13

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror p. 78

- ^ Thomas Norman Conquest p. 18

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest p. 132

- ^ a b Huscroft Norman Conquest pp. 118–119

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror pp. 79–81

- ^ a b c Huscroft Norman Conquest pp. 120–123

- ^ a b c Carpenter Struggle for Mastery p. 72

- ^ Marren 1066 p. 93

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest p. 124

- ^ Lawson Battle of Hastings pp. 180–182

- ^ Marren 1066 pp. 99–100

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest p. 126

- ^ Carpenter Struggle for Mastery p. 73

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest pp. 127–128

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest p. 129

- ^ Williams "Godwine, earl of Wessex" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ Walker Harold p. 181

- ^ Rex Harold II p. 254

- ^ Huscroft Norman Conquest p. 131

- ^ a b Huscroft Norman Conquest pp. 131–133

- ^ a b c d Huscroft Norman Conquest pp. 138–139

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror p. 423

- ^ a b Carpenter Struggle for Mastery pp. 75–76

- ^ a b c Huscroft Ruling England pp. 57–58

- ^ a b Carpenter Struggle for Mastery pp. 76–77

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror p. 225

- ^ a b c Bates William the Conqueror pp. 106–107

- ^ a b Barlow English Church 1066–1154 p. 59

- ^ Turner "Richard Lionheart" French Historical Studies p. 521

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 221–222

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 223–225

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror pp. 107–109

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 228–229

- ^ a b c Bates William the Conqueror p. 111

- ^ a b Bates William the Conqueror p. 112

- ^ a b c d Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 231–233

- ^ a b Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 230–231

- ^ Pettifer English Castles pp. 161–162

- ^ a b Williams "Ralph, earl" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ Lewis "Breteuil, Roger de, earl of Hereford" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror pp. 181–182

- ^ a b Bates William the Conqueror pp. 183–184

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror pp. 185–186

- ^ Douglas and Greenaway, p. 158

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 238–239

- ^ a b Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 240–241

- ^ a b Bates William the Conqueror p. 188

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror p. 189

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror p. 193

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 243–244

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror pp. 196–198

- ^ Pettifer English Castles p. 151

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror pp. 147–148

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror pp. 154–155

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror pp. 148–149

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror pp. 152–153

- ^ Young Royal Forests pp. 7–8

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror pp. 118–119

- ^ a b c Bates William the Conqueror pp. 138–141

- ^ a b Bates William the Conqueror pp. 133–134

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror pp. 136–137

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror pp. 151–152

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror p. 150

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror pp. 198–202

- ^ a b c Bates William the Conqueror pp. 202–205

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror pp. 207–208

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 362–363

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror p. 363 footnote 4

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror pp. 208–209

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror pp. 210–211

- ^ a b Clanchy England and its Rulers pp. 31–32

- ^ Searle Predatory Kinship p. 232

- ^ Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 4–5

- ^ Thompson "Robert, duke of Normandy" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ Barlow "William II" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ a b c Fryde, et al., Handbook of British Chronology, p. 35

- ^ a b c d e Van Houts "Adelida" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ a b c Salazar y Acha "Contribución al estudio" Anales de la Real Academia pp. 307–308

- ^ a b c Reilly Kingdom of Leon-Castile p. 47

- ^ Canal Sánchez-Pagín "Jimena Muñoz" Anuario de Estudios Medievales pp. 12–14

- ^ Given-Wilson and Curteis Royal Bastards p. 59

References

- required)

- ISBN 0-582-50236-5.

- required)

- ISBN 0-7524-1980-3.

- required)

- Canal Sánchez-Pagín, José María (2020). "Jimena Muñoz, Amiga de Alfonso VI". Anuario de Estudios Medievales (in Spanish). 21: 11–40. .

- ISBN 0-14-014824-8.

- ISBN 1-4051-0650-6.

- ISBN 0-312-21886-9.

- ISBN 0-582-36981-9.

- OCLC 399137.

- Douglas, David C.; Greenaway, G. W. (1981). English Historical Documents, 1042–1189. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-43951-1.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

- Given-Wilson, Chris; Curteis, Alice (1995). The Royal Bastards of Medieval England. New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN 1-56619-962-X.

- Huscroft, Richard (2009). The Norman Conquest: A New Introduction. New York: Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-1155-2.

- Huscroft, Richard (2005). Ruling England 1042–1217. London: Pearson/Longman. ISBN 0-582-84882-2.

- Lawson, M. K. (2002). The Battle of Hastings: 1066. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-1998-6.

- Lewis, C. P. (2004). "Breteuil, Roger de, earl of Hereford (fl. 1071–1087)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. required)

- ISBN 0-85052-953-0.

- Miller, Sean (2001). "Ætheling". In ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Pettifer, Adrian (1995). English Castles: A Guide by Counties. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell. ISBN 0-85115-782-3.

- Potts, Cassandra (2002). "Normandy, 911–1144". In Harper-Bill, Christopher; Van Houts, Elisabeth M. C. (eds.). A Companion to the Anglo-Norman World. Boydell. pp. 19–42.

- Reilly, Bernard F. (1988). The Kingdom of Leon-Castile Under Alfonso VI. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05515-2.

- Rex, Peter (2005). Harold II: The Doomed Saxon King. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7394-7185-2.

- Salazar y Acha, Jaime de (1992–1993). "Contribución al estudio del reinado de Alfonso VI de Castilla: algunas aclaraciones sobre su política matrimonial". Anales de la Real Academia Matritense de Heráldica y Genealogía (in Spanish). 2: 299–336.

- Searle, Eleanor (1988). Predatory Kinship and the Creation of Norman Power, 840–1066. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06276-0.

- Thomas, Hugh (2007). The Norman Conquest: England after William the Conqueror. Critical Issues in History. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7425-3840-5.

- Thompson, Kathleen (2004). "Robert, duke of Normandy (b. in or after 1050, d. 1134)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. required)

- Turner, Ralph V. (1998). "Richard Lionheart and the Episcopate in His French Domains". French Historical Studies. 21 (4 Autumn): 517–542. S2CID 159612172.

- van Houts, Elizabeth (2004). "Adelida (Adeliza) (d. before 1113)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. required)

- van Houts, Elisabeth (2002). "Les femmes dans l'histoire du duché de Normandie (Women in the history of ducal Normandy)". Tabularia "Études" (in French) (2): 19–34. S2CID 193557186.

- Walker, Ian (2000). Harold the Last Anglo-Saxon King. Gloucestershire, UK: Wrens Park. ISBN 0-905778-46-4.

- "William the Conqueror". The Royal Family. London: the Royal Household. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ISBN 1-85285-382-4.

- required)

- required)

- Young, Charles R. (1979). The Royal Forests of Medieval England. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-7760-0.