Serer people

Lebou people |

The Serer people (

The Serer people originated in the

The Serer people have been historically noted as an ethnic group practicing elements of both matrilineality and patrilineality that long, violently resisted the expansion of Islam since the 11th century.[19][20][21][22][23] They fought against jihads in the 19th century, and subsequently opposed French colonial rule - resulting in Serer victory at the famous Battle of Djilass (13 May 1859), and the French Empire taking revenge against them at the equally famous Battle of Logandème that same year.[24][25][26][27][28]

In the 20th century, most of the Serer converted to Islam (Sufism[29]), but some are Christians or follow their traditional religion.[24] Despite resisting Islamization and jihads for almost a millenia - having been persecuted for centuries, most of the Serers who converted to Islam converted as recently as the 1990s,[24] in part, trying to escape discrimination and disenfranchisement by the majority Muslim group surrounding them, who still view the Serers as "the object of scorn and prejudice."[30][31]

The Serer society, like other ethnic groups in Senegal, has had social stratification featuring endogamous

Other spelling

The Serer people are also referred to as:

- Serer proper: Seereer or Sereer

- French: Sérère

- Other spelling: Sarer, Kegueme (possible corruption of Serer-Dyegueme), Serrere, Serere, Ceereer/Cereer (from Ceereer ne ("the Seereer people" in Serer, found in early European spelling/maps), and sometimes wrongly Serre

Demographics and distribution

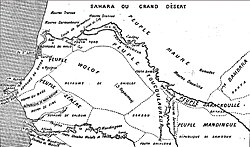

The Serer people are primarily found in contemporary Senegal, particularly in the west-central part of the country, running from the southern edge of Dakar to the border of The Gambia. The Serer include the various Serer peoples of which the Seex people (pronounced Seh) and the most numerous.

The Serer-Noon occupy the ancient area of Thiès in modern-day Senegal. The Serer-Ndut are found in southern Cayor and north west of ancient Thiès. The Serer-Njeghen occupy old Baol; the Serer-Palor occupy the west central, west southwest of Thiès and the Serer-Laalaa occupy west central, north of Thiès and the Tambacounda area.[38][39]

The Serer people are diverse. Although they lived throughout the Senegambia region, they are more numerous in places such as old Baol, Sine, Saloum and in The Gambia, which was a colony of the Kingdom of Saloum. There they occupy parts of old Nuimi and Baddibu as well as the Gambian Kombo.[38]

- Senegal: 2,941,545.6 million (2023 estimates) (16% of total population)[1][3]

- The Gambia: 88,316.45 (2019-2020 estimates, 3.5% of total population according to Gambia) [2][5]

- Mauritania: 5,000[4][40]

The Seex (also called Sine-Sine, Serer, Seh, Seeh, or

"Sérère" is the standard spelling in French speaking Senegal and Mauritania.Ethnonym

The meaning of the word "Serer" is uncertain. Professor Issa Laye Thiaw view it as ancient and sacred, and pre-Islamic, and thus rejects the following four modern definitions rooted in their historical rejection of Islam:[41]

- From the Serer Wolof word reer meaning 'misplaced', i.e. doubting the truth of Islam.

- From the Serer Wolof expression seer reer meaning "to find something hidden or lost."

- From "the Arabic word seereer meaning sahir magician or one who practices magic (an allusion to the traditional religion)"

- From a Pulaar word meaning separation, divorce, or break, again referring to rejecting Islam.[41]

Professor Cheikh Anta Diop, citing the work of 19th-century French archeologist and Egyptologist, Paul Pierret, states that the word Serer means "he who traces the temple."[25] Diop continued:

"That would be consistent with their present religious position: they are one of the rare Senegalese populations who still reject Islam. Their route is marked by the upright stones found at about the same latitude from Ethiopia all the way to the Sine-Salum, their present habitat."[25]

R. G. Schuh have refuted Diop's thesises in general.[42] Professor Molefi Kete Asante et al. agrees pretty much with Professor Diop, and posits that, "they are an ancient people whose history reaches deep into the past..." and that would be consistent with their "strong connection to their ancient religious past".[43]

History

Professor Dennis Galvan writes that "The oral historical record, written accounts by early Arab and European explorers, and physical anthropological evidence suggest that the various Serer peoples migrated south from the Fuuta Tooro region (Senegal River valley) beginning around the eleventh century when Islam first came across the Sahara."

If one is to believe the economist and demographer Étienne Van de Walle[44] who gave a slightly later date for their ethnogenesis, writing that "The formation of the Sereer ethnicity goes back to the thirteenth century, when a group came from the Senegal River valley in the north fleeing Islam, and near Niakhar met another group of Mandinka origin, called the Gelwar, who came from the southeast (Gravrand 1983). The actual Sereer ethnic group is a mixture of the two groups, and this may explain their complex bilinear kinship system".[45]

Their own oral traditions recite legends that relate their being "part of, or closely related to, the same group as the ancestors of today's Tukulor" (

After the

Last Serer kings

The last kings of

After their deaths, the Serer Kingdoms of Sine and Saloum were incorporated into independent Senegal, which had gained its independence from France in 1960. The Serer kingdoms of Sine and Saloum are two of the few pre-colonial African kingdoms whose royal dynasty survived up to the 20th century.[52]

In 2017 and 2019, the Serers of Saloum and Sine (respectively) decided to reinstate their monarchies from the same

Serer kingdoms

Serer kingdoms included the Kingdom of Sine and the Kingdom of Saloum. In addition to these twin Serer kingdoms, the Serer ruled in the

The Faal (var: Fall) paternal dynasty of

All the kings that ruled Serer Kingdoms had Serer surnames, with the exception of the Mboge and Faal paternal dynasties whose reigns are very recent. They did not provide many kings.[65]

Religion

| Part of a series on |

| Serers and Serer religion |

|---|

|

The Serer traditional religion is called a ƭat Roog ('the way of the Divine'). It believes in a universal Supreme Deity called

In contemporary times, about 85% of the Serers are Muslim,[24] while others are Christian.[6] Some Serer still follow Serer spiritual beliefs.[68][69]

According to James Olson, professor of History specializing in Ethnic Group studies, the Serer people "violently resisted the expansion of Islam" by the Wolof people in the 19th century. They were a target of the 1861 jihad led by the Mandinka cleric Ma Ba Jaxoo.[24] The inter-ethnic wars involving the Serer continued till 1887, when the French colonial forces conquered Senegal. Thereafter, the conversion of the Serer people accelerated.

By the early 1910s, about 40% of the Serer people had adopted Islam, and by the 1990s about 85% of them were Muslims.

Society

Occupation

The Serer practice trade, agriculture, fishing, boat building and animal husbandry. Traditionally the Serer people have been farmers and landowners.[71] Although they practice animal husbandry, they are generally less known for that, as in the past, Serer nobles entrusted their herds to the pastoralist Fula, a practice that continues today.[72]

However, they are known for their mixed-farming.

Social stratification

The Serer people have traditionally been a socially stratified society, like many West African ethnic groups with castes.[32][34]

The mainstream view has been that the Mandinka (or Malinka)

In other regions where Serer people are found, state JD Fage, Richard Gray and Roland Oliver, the Wolof and Toucouleur peoples introduced the caste system among the Serer people.[78]

The social stratification historically evidenced among the Serer people has been, except for one difference, very similar to those found among Wolof, Fulbe, Toucouleur and Mandinka peoples found in Senegambia. They all have had strata of free nobles and peasants, artisan castes, and slaves. The difference is that the Serer people have retained a matrilineal inheritance system.[79] According to historian Martin A. Klein the caste systems among the Serer emerged as a consequence of the Mandinka people's Sine-Saloum guelowar conquest, and when the Serer people sought to adapt and participate in the new Senegambian state system.[79]

The previously held view that the Serer only follow a matrilineal structure is a matter of conjecture. Although matrilineality (tiim in Serer) is very important in Serer culture, the Serer follow a bilineal system. Both matrilineality and patrilineality are important in Serer custom. Inheritance depends on the nature of the asset being inherited. That is, whether the asset is a maternal (ƭeen yaay) or paternal (kucarla) asset.[19][20][21][22][23]

The hierarchical highest status among the Serer people has been those of hereditary nobles and their relatives, which meant blood links to the Mandinka conquerors.[80][81] Below the nobles, came tyeddo, or the warriors and chiefs who had helped the Mandinka rulers and paid tribute. The third status, and the largest strata came to be the jambur, or free peasants who lacked the power of the nobles. Below the jambur were the artisan castes, who inherited their occupation. These castes included blacksmiths, weavers, jewelers, leatherworkers, carpenters, griots who kept the oral tradition through songs and music. Of these, all castes had a taboo in marrying a griot, and they could not be buried like others. Below the artisan castes in social status have been the slaves, who were either bought at slave markets, seized as captives, or born to a slave parent.[80]

The view that the jambur (or jambuur) caste were among the lower echelons of society is a matter of debate. The jaraff, who was the most important person after the king (Maad a Sinig or Maad Saloum) came from the jambur caste. The Jaraff was the equivalent of a prime minister. He was responsible for organising the coronation ceremony and for crowning the Serer kings. Where a king dies without nominating an heir (buumi), the Jaraff would step in and reign as regent until a suitable candidate can be found from the royal line. The noble council that was responsible for advising the king was also made up of jamburs as well as the paar no maad (or buur/bur kuvel/guewel) - the chief griot of the king, who was extremely powerful and influential, and very rich in land and other assets. The paar no maad who also came from the griot caste were so powerful that they could influence a king's decision as to whether he goes to war or not. They told the king what to eat, and teach them how to eat, how to walk, to talk and to behave in society. They always accompany the king to the battlefield and recount the glory or bravery of his ancestors in battle. They retain and pass down the genealogy and family history of the king. The paar no maad could make or break a king, and destroy the entire royal dynasty if they so wish. The abdication of Maad Saloum Fakha Boya Fall from the throne of Saloum was led and driven by his own paar no maad (or bur kevel). After being forced to abdicate, he was chased out of Saloum. During the reign of Maad a Sinig Sanmoon Faye – king of Sine, one of the key notables who plotted to dethrone the king was the king's own paar no maad. After influencing the king's own estranged nephew Prince Semou Mak Joof to take up arms against his uncle, the Prince who despised his uncle took up arms with the support of the paar no maad and other notables. The Prince was victorious and was crowned Maad a Sinig (King of Sine). That is just a sample of the power of the paar no maad who was also a member of the griot caste.[82][83]

The slave castes continue to be despised, they do not own land and work as tenant farmers, marriage across caste lines is forbidden and lying about one's caste prior to marriage has been a ground for divorce.[citation needed][84] The land has been owned by the upper social strata, with the better plots near the villages belonging to the nobles.[81][85] The social status of the slave has been inherited by birth.[86]

Serer religion and culture forbids slavery.[35][36] "To enslave another human being is regarded as an enslavement of their soul thereby preventing the very soul of the slave owner or trader from entering Jaaniiw – the sacred place where good souls go after their physical body has departed the world of the living. In accordance with the teachings of Seereer religion, bad souls will not enter Jaaniiw. Their departed souls will not be guided by the ancestors to this sacred abode, but will be rejected thereby making them lost and wandering souls. In order to be reincarnated (Ciiɗ, in Seereer) or sanctified as a Pangool in order to intercede with the Divine [ Roog ], a person's soul must first enter this sacred place." As such, the Serers who were the victims of Islamic jihads and enslavements did not participate much in slavery and when they do, it was merely in revenge.[36][35] This view is supported by scholars such as François G. Richard who posits that:

- The Kingdom of Sine remained a modest participant in the Atlantic system, secondary to the larger Wolof, Halpulaar [ Fula and Toucouleur people ] or Mandinka polities surrounding it on all sides... As practices of enslavement intensified among other ethnic groups during the 18th century, fuelling a lucrative commerce in captives and the rise of internal slavery, the Siin may have been demoted to the rank of second player, in so far as the kingdom was never a major supplier of captives.[37]

The Serer ethnic group is rather diverse, and as Martin A. Klein notes, the institution of slavery did not exist among the Serer-Noon and N'Dieghem.[87]

Culture

Wrestling and sports

Music

"The Serer people are known especially for their rich knowledge of vocal and rhythmic practices that infuse their everyday language with complex overlapping cadences and their ritual with intense collaborative layerings of voice and rhythm."

The

The

Serer relations to Moors

In the pre-colonial era,

Joking relationship (Maasir or Kalir)

Serers and Toucouleurs are linked by a bond of "cousinage". This is a tradition common to many ethnic groups of West Africa known as Maasir (var : Massir) in Serer language (Joking relationship) or kal, which comes from kalir (a deformation of the Serer word kucarla meaning paternal lineage or paternal inheritance). This joking relationship enables one group to criticise another, but also obliges the other with mutual aid and respect. The Serers call this Maasir or Kalir. This is because the Serers and the Toucouleurs are related – according to Wiliam J. foltz "Tukulor are a mixture of Fulani and Serer"[97] The Serers also maintain the same bond with the Jola people with whom they have an ancient relationship based on the legend of Jambooñ and Agaire.[46] In the Serer ethnic group, this same bond exists between the Serer patronym, for example between Joof and Faye families.[98]

Many

Serer languages

Most people who identify themselves as Serer speak the

About 200,000 Serer speak various

| Cangin languages and Serer proper | % Similarity with Serer-Sine | % Similarity with Noon | % Similarity with Saafi | % Similarity with Ndut | % Similarity with Palor | % Similarity with Lehar (Laalaa) | Areas they are predominantly found | Estimated population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Lehar language (Laalaa) |

22 | 84 | 74 | 68 | 68 | N/A | West central, north of Thies, Pambal area, Mbaraglov, Dougnan; Tambacounda area. Also found in the Gambia | 12,000 (Senegal figures only) (2007) |

| Ndut language | 22 | 68 | 68 | N/A | 84 | 68 | West central, northwest of Thiès | 38,600 (Senegal figures only (2007) |

| Noon language | 22 | N/A | 74 | 68 | 68 | 84 | Thiès area. | 32,900 (Senegal figures only (2007) |

| Palor language | 22 | 68 | 74 | 84 | N/A | 68 | West central, west southwest of Thiès | 10,700 (Senegal figures only (2007) |

Saafi language

|

22 | 74 | N/A | 68 | 74 | 74 | Triangle southwest of and near Thiès (between Diamniadio, Popenguine, and Thiès) | 114,000 (Senegal figures only (2007) |

| Serer-Sine language (not a Cangin language) | N/A | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | West central; Saloum River valleys. Also in the Gambia and small number in Mauritania |

1,154,760 (Senegal – 2006 figures); 31,900 (the Gambia – 2006 figures) and 3,500 (Mauritania 2006 figures)[105] |

Serer patronyms

Some common Serer surnames are:

- Joof or Diouf

- Faye

- Ngom or Ngum

- Sène (var : Sene or Sain)

- Diagne

- Dione or Jon

- N'Diaye

- Tine

- Khan

- Lame

- Loum

- Ndaw or Ndao

- Diene (var : Diène) or Jein

- Thiaw

- Senghor

- Ndur

- Ndione

- Gadio

- Sarr

- Kama

- Chorr or Thior

- Charreh or Thiare

- Jaay) etc... are all typical Serer surnames.

Notable Serer people

- Léopold Sedar Senghor, first president of Senegal from 1960 to 1980

- Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie

- Ngalandou Diouf, the first African elected to office in French West Africa

- Al Njie, Senegalese footballer

- Marième Faye Sall – current First Lady of Senegal (as of 2020); wife of President Macky Sall (whose mother is Serer).[106]

- Fallou Diagne, Senegalese footballer

- Fatou Diome, Senegalese author

- Safi Faye, Senegalese film director and ethnologist

- Alhaji Alieu Ebrima Cham Jooflate Senegambian historian, politician and colonial-era advocate for Gambia's independence

- Bai Modi Joof, Gambian lawyer and champion of free speech

- Laïty Kama, Senegalese Lawyer and the first president of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda

- Issa Laye Thiaw, Senegalese historian and theologian

- Alioune Sarr, Senegalese historian and politician

- Isatou Njie-Saidy, former Vice-president of Gambia

- Bassirou Diomaye Faye, fifth president of Senegal

- Yandé Codou Sène, Senegalese griot and musician

- Youssou N'Dour, Senegalese musician

- Mame Biram Diouf, Senegalese footballer

- Robert Diouf, Senegalese wrestler

- El Hadji Diouf, Senegalese footballer

- Khaby Lame, Senegalese-born Italian social media personality

- Ismaïla Sarr, Senegalese footballer

- Malang Sarr, Senegalese footballer

- Oulimata Sarr, Senegalese politician

- Moustapha Name, Senegalese footballer

- Ousmane Ndong, Senegalese footballer

- Abdoulaye Faye, Senegalese footballe

- Joseph Henry Joof, Gambian lawyer and politician

- Marie Samuel Njie, Gambian singer,

- Pap Saine, Gambian editor and publisher

- Ibrahima Sarr, Mauritanian journalists and politician

See also

|

Other ethnic groups

Senegal

|

|

Films

|

|

Notes

- ^ a b c CIA World Factbook, Senegal (2023 estimates) - archive [1]

- ^ a b c CIA World Fackbook

- ^ a b Agence Nationale de Statistique et de la Démographie. Estimated figures for 2007 in Senegal alone

- ^ a b c d This is an old figure which has not updated on Joshua Project. "Serer in Mauritania." [2] (retrieved 4 March 2025). It is however more recent than the following 2000 source based on a 1988 census:

- 3,500 (estimated in 2000): African Census Analysis Project (ACAP). University of Pennsylvania. Ethnic Diversity and Assimilation in Senegal: Evidence from the 1988 Census by Pierre Ngom, Aliou Gaye and Ibrahima Sarr. 2000

- ^ a b National Population Commission Secretariat (30 April 2005). "2013 Population and Housing Census: Spatial Distribution" (PDF). Gambia Bureau of Statistics. The Republic of The Gambia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 January 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-674-50492-9.

- ^ "Charisma and Ethnicity in Political Context: A Case Study in the Establishment of a Senegalese Religious Clientele", Leonardo A. Villalón, Journal of the International African Institute, Vol. 63, No. 1 (1993), p. 95, Cambridge University Press on behalf of the International African Institute

- ISBN 9780521032322

- ^ a b Bulletin de la Société de géographie, Volume 26. Société de Géographie (1855), pp. 35 - 36. [3] (retrieved 7 March 2025). Quote:

- "La nation sérère, aujourd'hui dispersée en plusieurs petits États sur la côte ou refoulée dans les bois de l'intérieur, doit être une des plus anciennes de la Sénégambie."

- ^ Maury, Alfred, Rapports à la Soc. de géogr, Volume 1. (1855). p. 25 [4] (retrieved 7 March 2025)

- ^ Marty, Paul, L'Islám en Mauritanie et au Sénégal. E. Leroux (1916), p. 49

- ^ Senegal, CIA Factsheet (retrieved 7 March 2025)

- ^ [5] Ethnologue.com

- ^ Gambia, CIA Factsheet (retrieved 7 March 2025)

- ^ a b c Galvan, Dennis Charles, The State Must Be Our Master of Fire: How Peasants Craft Culturally Sustainable Development in Senegal, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004 p. 51

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7614-4481-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-03232-2., Quote: "Serer oral tradition recounts the group's origins in the Senegal River valley, where it was part of, or closely related to, the same group as the ancestors of today's Tukulor."

- ^ Natural Resources Research, UNESCO, Natural resources research, Volume 16, Unesco (1979), p. 265

- ^ ISBN 2738451969

- ^ a b Lamoise, LE P., Grammaire de la langue Serer (1873)

- ^ a b Becker, Charles: Vestiges historiques, trémoins matériels du passé clans les pays sereer, Dakar (1993), CNRS-ORSTOM [6]

- ^ a b Gastellu, Jean-Marc, Petit traité de matrilinarité. L'accumulation dans deux sociétés rurales d'Afrique de l'Ouest, Cahiers ORSTOM, série Sciences Humaines 4 (1985) [in] Gastellu, Jean-Marc, Matrilineages, Economic Groups and Differentiation in West Africa: A Note, O.R.S.T.O.M. Fonds Documentaire (1988), pp 1, 2–4 (pp 272–4), 7 (p 277) [7]

- ^ ISBN 2865374874 [8]

- ^ ISBN 978-0-313-27918-8.

- ^ a b c Pierret, Paul, "Dictionnaire d'archéologie égyptienne", Imprimerie nationale 1875, p. 198-199 [in] Diop, Cheikh Anta, Precolonial Black Africa, (trans: Harold Salemson), Chicago Review Press, 1988, p. 65

- ^ a b See Godfrey Mwakikagile in Martin A. Klein. Islam and Imperialism in Senegal Sine-Saloum, 1847–1914, Edinburgh at the University Press (1968)

- ^ Sagne, Mohamadou, VILLAGE DE DJILASS: L’EXPLOITATION DE village-de-djilass-lexploitation-de, Le soleil (15 Nov 2021), [in] Seneplus. [9] (retrieved 3 Mar 2025)

- ^ OG, Des cadres du Sine veulent faire construire un mausolée pyramidal dédié au roi Sann Moon Faye, Sud Quotidien (19 Aug 2023). [10] (retrieved 3 March 2025)

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-03232-2.

- ISBN 1-4269-7117-6

- ISBN 9987-9322-2-3

- ^ ISBN 978-1-107-65723-6., Quote:"One reason for the low salience of ethnic identity is because, like some other West African societies, many ethnic groups in Senegal are structured by caste. For example, the Wolof, Serer, and Pulaar-speaking Toucouleur are all caste societies."

- ISBN 978-0-8047-0621-6.

- ^ S2CID 162509491., Quote: "[Castes] are found among the Soninke, the various Manding-speaking populations, the Wolof, Tukulor, Senufo, Minianka, Dogon, Songhay, and most Fulani, Moorish and Tuareg populations, (...) They are also found among (...) and Serer groups."

- ^ a b c Thiaw, Issa Laye, La Religiosité des Sereer, Avant et Pendant Leur Islamisation. Éthiopiques, No: 54, Revue Semestrielle de Culture Négro-Africaine. Nouvelle Série, Volume 7, 2e Semestre 1991 [11] Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c The Seereer Resource Centre, Seereer Lamans and the Lamanic Era (2015) [in] [12]

- ^ a b Richard, François G., Recharting Atlantic encounters. Object trajectories and histories of value in the Siin (Senegal) and Senegambia. Archaeological Dialogues 17(1) 1–27. Cambridge University Press 2010)

- ^ a b c Patience Sonko-Godwin. Ethnic Groups of The Senegambia Region. A Brief History. p32. Sunrise Publishers Ltd. Third Edition, 2003. ASIN B007HFNIHS

- ^ a b Ethnologue.com. Languages of Senegal. 2007 figures

- ^ 3500 estimated in 2000 from 1988 census. See: African Census Analysis Project (ACAP). University of Pennsylvania. Ethnic Diversity and Assimilation in Senegal: Evidence from the 1988 Census by Pierre Ngom, Aliou Gaye and Ibrahima Sarr. 2000

- ^ a b "La Religiosité des Sereer, avant et pendant leur Islamisation". Éthiopiques, No: 54, Revue Semestrielle de Culture Négro-Africaine. Nouvelle Série, Volume 7, 2e Semestre 1991. By Issa Laye Thiaw

- ^ Russell G. Schuh, "The Use and Misuse of Language in the Study of African History", Ufahamu, 1997, 25(1), p. 36-81

- ISBN 9781506317861 [13](retrieved 2 March 2025)

- ^ Étienne Van de Walle was not a historian or a professor of history. He had a degree in economics and was a demographer/researcher but was not an academic historian. See: Leridon, Henri. “Etienne van de Walle 1932-2006.” Population (English Edition, 2002-), vol. 61, no. 1/2, 2006, pp. 11–13. JSTOR, [14]. Accessed 5 Aug. 2024.

- ISBN 978-0765616197.

- ^ a b According to both Serer and Jola tradition, they trace their descent from Jambooñ (also spelt : Jambonge, Jambon, etc.) and Agaire (variantes : Ougeney, Eugeny, Eugene, etc.). For the legend of Jambooñ and Agaire, see :

- (in French) Ndiaye, Fata, "LA SAGA DU PEUPLE SERERE ET L’HISTOIRE DU SINE", [in] Ethiopiques n° 54 revue semestrielle de culture négro-africaine Nouvelle série volume 7, 2e semestre (1991) "Le Siin avant les Gelwaar" Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- (in English) Taal, Ebou Momar, "Senegambian Ethnic Groups : Common Origins and Cultural Affinities Factors and Forces of National Unity, Peace and Stability", [in] The Point, (2010)[15]

- ISBN 0-521-22803-4

- ^ Dawda Faal. Peoples and empires of Senegambia: Senegambia in history, AD 1000–1900, p17. Saul's Modern Printshop (1991)

- ^ Marcel Mahawa Diouf. Lances mâles: Léopold Sédar Senghor et les traditions Sérères, p54. Published by: Centre d'études linguistiques et historiques par tradition orale (1996)

- ^ Ibn Abi Zar, p89

- ^ See Martin Klein p 62-93

- ^ See Sarr; Bâ, also: Klein: Rulers of Sine and Saloum, 1825 to present (1969).

- ^ Leral.net, "Guédel Mbodj et Thierno Ndaw intronisés: Un Saloum, deux Buur." (23 May 2017) [16] (retrieved 4 March 2025)

- ^ Xibaaru, "Situation politique les chefs coutumiers banissent la violence." (24 February 2023) [17] (retrieved 4 March 2025

- ^ Boursine.org (the official website of the Royal Institution of Sine), "Intronisation du Maad sinig Niokhobaye Diouf" (posted on 12 February 2020) [18] (retrieved: 4 March 2025)

- ^ Actu Sen, "Intronisation du Roi “Maad a Sinig” de Diakhao : 51 ans après, le Sine restaure la couronne." By Matar Diouf (10 February 2020) [19] (retrieved: 4 March 2025)

- ^ Le Quotidien, "Caravane de la paix : Les rois d’Oussouye et du Sine apôtres de la bonne parole." By Alioune Badara Ciss (27 May 2023) [20] (retrieved: 4 March 2025)

- ^ The Point, "King of Madala Sinic [Maad a Sinig] visits Senegalese Embassy in Gambia." By Adama Jallow (23 May 2023).[21] (retrieved: 4 March 2024)

- ^ ISBN 0-8108-1369-6

- ^ a b Institut fondamental d'Afrique noire. "Bulletin de l'Institut fondamental d'Afrique noire," Volume 38. IFAN, 1976. pp 557–504

- ISBN 0-299-14334-1

- ISBN 0-521-59760-9

- ISBN 9780907015857

- ^ Clark, Andrew F., & Philips, Lucie Colvin, Historical Dictionary of Senegal. Second Edition (1994)

- Maad a Sinig Mahecor Joof(1969)

- ^ Salif Dione, L’Education traditionnelle à travers les chants et poèmes sereer, Dakar: Université de Dakar, 1983, 344 p. (Thèse de 3e cycle)

- ^ Henry Gravrand, La civilisation Sereer, Pangool, Dakar: Nouvelles Editions Africaines (1990)

- ^ See Godfrey Mwakikagile. The Gambia and its People: Ethnic Identities and cultural integration in Africa, p133

- ISBN 0-7614-4481-5

- ISBN 978-1-316-77290-4.

- ISBN 9987-16-023-9

- ISBN 0-85229-961-3

- ISBN 9966-46-025-X

- ^ Dennis Galvan. Market Liberalization as a Catalyst for Ethnic Conflict. Department of Political Science & International Studies Program. The University of Oregon. pp 9–10

- ^ a b Diouf, Babacar Sédikh [in] Ngom, Biram, La question Gelwaar et l’histoire du Siin, Dakar, Université de Dakar, 1987, p 69

- SenegambianMuslim communities as well as the European conquerors who viewed the Serer as ""idolaters of great cruelty." For more on this, see Kerr, Robert, A general history of voyages and travels to the end of the 18th century, J. Ballantyne & Co., 1811, p. 239; (in Italian) Giovanni Battista Ramusio, Primo volume delle nauigationi et viaggi nel qual si contiene la descrittione dell'Africa, et del paese del Prete Ianni, con varii viaggi, dal mar Rosso a Calicut & infin all'isole Molucche, dove nascono le Spetiere et la navigatione attorno il mondo: li nomi de gli auttori, et le nauigationi..., Published by appresso gli heredi di Lucantonio Giunti, 1550, p. 113; (in Portuguese) Academia das Ciências de Lisboa. Collecção de noticias para a historia e geografia das nações ultramarinas: que vivem nos dominios portuguezes, ou lhes são visinhas, Published by Typ. da Academia, 1812, p. 51

- ^ Sarr, Alioune, Histoire du Sine-Saloum (Sénégal) . Introduction, bibliographie et notes par Charles Becker. "Version légèrement remaniée par rapport à celle qui est parue en 1986–87." p 19

- ISBN 978-0-521-20413-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8047-0621-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8047-0621-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-316-77290-4.

- ^ Sarr, Alioune, Histoire du Sine-Saloum, Introduction, bibliographie et Notes par Charles Becker, BIFAN, Tome 46, Serie B, n° 3–4, 1986–1987. pp 28–30, 46, 106–9

- ISBN 9780804706216

- ISBN 978-1-5026-3642-3.

- ISBN 978-0-520-06363-1.

- ISBN 978-0-521-20413-2.

- ^ Klein (1968), p. 165

- ISBN 9987-16-023-9

- ISBN 1-59213-420-3

- ^ David P. Gamble. The Wolof of Senegambia: together with notes on the Lebu and the Serer, p77. International African Institute, 1957

- ^ a b Ali Colleen Neff. Tassou: the Ancient Spoken Word of African Women. 2010.

- ISBN 1-59213-420-3

- ISBN 9781841629131 [22]

- ^ "Sarkodie and Stonebwoy listed among 'Top 10 Hottest African Artistes' making global waves" [in] Pulse, by David Mawuli (27 May 2015) [23]

- ^ "Nigeria: 10 Hottest African Artistes Making Global Waves" [in] AllAfrica.com, by Anthony Ada Abraham (28 May 2015) [24]

- ^ Abdou Bouri Bâ. Essai sur l’histoire du Saloum et du Rip. Avant-propos par Charles Becker et Victor Martin, p4

- ^ William J. Foltz. From French West Africa to the Mali Federation, Volume 12 of Yale studies in political science, p136. Published by Yale University Press, 1965

- ^ Galvan, Dennis Charles, "The State is Now the Master of Fire" (Adapting Institutions and Culture in Rural Senegal, Volume 1), University of California, Berkeley (1996), p. 65,

- ^ Becker, Charles, "Vestiges historiques, trémoins matériels du passé clans les pays sereer"

- ^ Variations : gamohou or gamahou

- ^ (in French) Diouf, Niokhobaye, « Chronique du royaume du Sine, suivie de Notes sur les traditions orales et les sources écrites concernant le royaume du Sine par Charles Becker et Victor Martin (1972)», . (1972). Bulletin de l'IFAN, tome 34, série B, no 4, 1972, pp 706–7 (pp 4–5), pp 713–14 (pp 9–10)

- ^ For more on Serer religious festivals, see : (in French) Niang, Mor Sadio, "CEREMONIES ET FÊTES TRADITIONNELLES", IFAN, [in] Éthiopiques, numéro 31 révue socialiste de culture négro-africaine 3e trimestre (1982) [25] Archived 24 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Martin A, Klein, p7

- ^ Lewis, M. Paul (ed.), 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. (Ethnologue.com – 2006 and 2007).

- ^ NB: 2006 Figures are taken in order to compare the population of the Serer in the respective countries.

- ^ Jeune Afrique, Sénégal : Marième Faye Sall, nouvelle première dame, 26 March 2012 by Rémi Carayol [26] (retrieved on 8 February 2020)

Bibliography

- Diouf, Mamadou & Leichtman, Mara, New perspectives on Islam in Senegal: conversion, migration, wealth, power, and femininity. Published by: Palgrave Macmillan. 2009. the University of Michigan. ISBN 0-230-60648-2

- Diouf, Mamadou, History of Senegal: Islamo-Wolof model and its outskirts. Maisonneuve & Larose. 2001. ISBN 2-7068-1503-5

- Gamble, David P., & Salmon, Linda K. (with Alhaji Hassan Njie), Gambian Studies No. 17. People of the Gambia. I. The Wolof with notes on the Serer and Lebou San Francisco 1985.

- Niang, Mor Sadio, "CEREMONIES ET FÊTES TRADITIONNELLES", IFAN, [in] Éthiopiques, numéro 31 révue socialiste de culture négro-africaine 3e trimestre (1982)

- Taal, Ebou Momar, Senegambian Ethnic Groups: Common Origins and Cultural Affinities Factors and Forces of National Unity, Peace and Stability. 2010

- Diouf, Niokhobaye. "Chronique du royaume du Sine." Suivie de notes sur les traditions orales et les sources écrites concernant le royaume du Sine par Charles Becker et Victor Martin. (1972). Bulletin de l'Ifan, Tome 34, Série B, n° 4, (1972)

- Berg, Elizabeth L., & Wan, Ruth, "Senegal". Marshall Cavendish. 2009.

- Mahoney, Florence, Stories of Senegambia. Publisher by Government Printer, 1982

- Daggs, Elisa . All Africa: All its political entities of independent or other status. Hasting House, 1970. ISBN 0-8038-0336-2

- Department of Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Hilburn Timeline of Art History. The Fulani/Fulbe People.

- Schuh, Russell G., The Use and Misuse of language in the study of African history. 1997

- Burke, Andrew & Else, David, The Gambia & Senegal, 2nd edition – September 2002. Published by Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd, page 13

- Nanjira, Daniel Don, African Foreign Policy and Diplomacy: From Antiquity to the 21st Century. Page 91–92. Published by ABC-CLIO. 2010. ISBN 0-313-37982-3

- Lombard, Maurice, The golden age of Islam. Page 84. Markus Wiener Publishers. 2003. ISBN 1-55876-322-8,

- Oliver, Roland Anthony, & Fage, J. D., Journal of African History. Volume 10. Published by: Cambridge University Press. 1969

- The African archaeological review, Volumes 17–18. Published by: Plenum Press, 2000

- Ajayi, J. F. Ade & Crowder, Michael, History of West Africa, Volume 1. Published by: Longman, 1985. ISBN 0-582-64683-9

- Peter Malcolm Holt, The Indian Sub-continent, south-East Asia, Africa and the Muslim West. Volume 2, Part 1. Published by: Cambridge University Press. 1977. ISBN 0-521-29137-2

- Page, Willie F., Encyclopedia of African history and culture: African kingdoms (500 to 1500). Volume 2. Published by: Facts on File. 2001. ISBN 0-8160-4472-4

- Ham, Anthony, West Africa. Published by: Lonely Planet. 2009. ISBN 978-1-74104-821-6

- Mwakikagile, Godfrey, Ethnic Diversity and Integration in the Gambia. Page 224

- Richard, François G., "Recharting Atlantic encounters. Object trajectories and histories of value in the Siin (Senegal) and Senegambia". Archaeological Dialogues 17 (1) 1–27. Cambridge University Press 2010

- Diop, Samba, The Wolof Epic: From Spoken Word to Written Text. "The Epic of Ndiadiane Ndiaye"

- Two studies on ethnic group relations in Africa – Senegal, The United Republic of Tanzania. Pages 14–15. UNESCO. 1974

- Galvan, Dennis Charles, The State Must Be Our Master of Fire: How Peasants Craft Culturally Sustainable Development in Senegal. Berkeley, University of California Press, 2004

- Klein, Martin A., Islam and Imperialism in Senegal Sine-Saloum, 1847–1914, Edinburgh University Press (1968)

- Colvin, Lucie Gallistel, Historical Dictionary of Senegal. Scarecrow Press/ Metuchen. NJ – London (1981) ISBN 0-8108-1885-X

- ISBN 9983-86-002-3

- Sonko Godwin, Patience, Ethnic Groups of The Senegambia Region, A Brief History. p. 32, Third Edition. Sunrise Publishers Ltd – The Gambia (2003). ASIN B007HFNIHS

- Clark, Andrew F., & Philips, Lucie Colvin, Historical Dictionary of Senegal. Second Edition (1994)

- Portions of this article were translated from the French language Wikipedia article fr:Sérères, 2008-07-08 and August 2011.

- Abbey, M T Rosalie Akouele, "Customary Law and Slavery in West Africa", Trafford Publishing (2011), pp. 481–482, ISBN 1-4269-7117-6

- Bulletin de la Société de géographie, Volume 26. Société de Géographie (1855), pp. 35 - 36. [27] (retrieved 7 March 2025)

- Marty, Paul, L'Islám en Mauritanie et au Sénégal. E. Leroux (1916), p. 49

- Maury, Alfred, Rapports à la Soc. de géogr, Volume 1. (1855). p. 25 [28] (retrieved 7 March 2025)

- ISBN 9781506317861 [29](retrieved 2 March 2025)

External links

- Moving from Teaching African Customary Laws to Teaching African Indigenous Law Archived 5 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. By Dr Fatou. K. Camara

- Ethnolyrical. Tassou: The Ancient Spoken Word of African Women[usurped]

- The Seereer Resource Centre

- Seereer Radio

- Seereer Resource Centre and Seereer Radio Podcast

- Seereer Heritage Press (publishing house)