Sunda clouded leopard: Difference between revisions

Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers 53,965 edits →Threats: + img + int link |

Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers 53,965 edits →Threats: extended with ref |

||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

== Threats == |

== Threats == |

||

[[File:Riau deforestation 2006.jpg|thumb|left|Deforestation in Sumatra for oil palm plantation]] |

[[File:Riau deforestation 2006.jpg|thumb|left|Deforestation in Sumatra for oil palm plantation]] |

||

Sunda clouded leopards being strongly [[arboreal]] are forest-dependent, and are increasingly threatened by habitat destruction following [[deforestation in Indonesia]] as well as in [[deforestation in Malaysia|Malaysia]].<ref name=iucn/> |

|||

Borneo is one of the world’s areas with the highest [[Deforestation in Borneo|deforestation]] rates. The island's [[rainforest]]s are destructed rapidly due to large-scale conversion to plantations, illegal logging, and forest fires. While in the mid-1980s forests still covered nearly three quarters of the island, by 2005 only |

|||

| ⚫ | 52% of Borneo was still forested. Deforestation has been continuing at a highly unsustainable rate over the last twenty to thirty years. The impact the continuation of this trend will have is irreversible in terms of the effects on forest ecosystems, on the species that inhabit them, as well as on the people who live sustainably from and in the forests. The forests are used to feed the world’s hunger for timber and other non-timber products, while the land is used to feed the need for vegetable oils. Both forests and land make way for human settlement. [[Wildlife trade#Illegal wildlife trade|Illegal trade in wildlife]] is a widely spread practice.<ref>{{cite |author= Rautner, M., Hardiono, M., Alfred, R. J. |year= 2005 |title= Borneo: treasure island at risk. Status of Forest, Wildlife, and related Threats on the Island of Borneo |publisher= WWF Germany |url= http://assets.panda.org/downloads/treasureislandatrisk.pdf}}</ref> |

||

Since the early 1970s, much of the forest cover has been cleared in southern Sumatra, in particular lowland [[tropical evergreen forest]]. Although protected areas have been established since the 1980s, protection measures did not slow down rates of forest loss, and failed to inhibit the expansion of agricultural encroachments. Forest stands inside protected areas have become severely fragmented and isolated, buffer forests have almost completely disappeared, and its remaining forest fragments are thin and elongated. This renders wildlife particularly vulnerable to human pressure.<ref>{{cite journal |author = Gaveaua, David L.A., Wandonoc, H., Setiabudid, F. |year =2007 |title= Three decades of deforestation in southwest Sumatra: Have protected areas halted forest loss and logging, and promoted re-growth? |journal = Biological Conservation |volume = 134 |issue = 4 |pages = 495–504 |url = http://www.aseanenvironment.info/Abstract/41014243.pdf}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | Borneo is one of the world’s areas with the highest [[Deforestation in Borneo|deforestation]] rates. The island's [[rainforest]]s are destructed rapidly due to large-scale conversion to plantations, [[illegal logging]], and forest fires. While in the mid-1980s forests still covered nearly three quarters of the island, by 2005 only 52% of Borneo was still forested. Deforestation has been continuing at a highly unsustainable rate over the last twenty to thirty years. The impact the continuation of this trend will have is irreversible in terms of the effects on forest ecosystems, on the species that inhabit them, as well as on the people who live sustainably from and in the forests. The forests are used to feed the world’s hunger for timber and other non-timber products, while the land is used to feed the need for vegetable oils. Both forests and land make way for human settlement. [[Wildlife trade#Illegal wildlife trade|Illegal trade in wildlife]] is a widely spread practice.<ref>{{cite |author= Rautner, M., Hardiono, M., Alfred, R. J. |year= 2005 |title= Borneo: treasure island at risk. Status of Forest, Wildlife, and related Threats on the Island of Borneo |publisher= WWF Germany |url= http://assets.panda.org/downloads/treasureislandatrisk.pdf}}</ref> |

||

==Conservation== |

==Conservation== |

||

Revision as of 11:47, 26 January 2011

| Sunda Clouded Leopard Temporal range: Early Pleistocene to Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Sunda Clouded Leopard in lower Kinabatangan River, eastern Sabah, Malaysia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | N. diardi

|

| Binomial name | |

| Neofelis diardi G. Cuvier, 1823

| |

| |

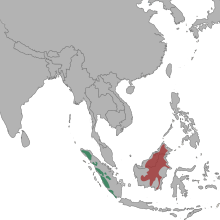

| Range of Sunda Clouded Leopard | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Felis diardii | |

The Sunda Clouded Leopard (Neofelis diardi), also known as the Sundaland Clouded Leopard and is a medium-sized wild

In 2008, the IUCN classified the species as vulnerable, with a total effective population size suspected to be fewer than 10,000 mature individuals, and a decreasing population trend.[1]

Previously, the species was known as the Bornean Clouded Leopard — a name publicised by the WWF in March 2007, quoting Dr. Stephen O'Brien of the U.S. National Cancer Institute as saying, "Genetic research results clearly indicate that the clouded leopard of Borneo should be considered a separate species".[4]

Characteristics

The Sunda clouded leopard is the largest

Its coat is marked with irregularly-shaped, dark-edged ovals which are said to be shaped like clouds, hence its common name. Though scientists have known of its existence since the early 19th century, it was positively identified as being a distinct species in its own right in 2006, having long been believed to be a subspecies of the mainland

Distribution and habitat

The Sunda clouded leopard is probably restricted to Borneo and Sumatra. In Borneo, they occur in lowland rainforest, and at lower density, in logged forest. Records in Borneo are below 1,500 m (4,900 ft). In Sumatra, they appear to be more abundant in hilly, montane areas. It is unknown if there are still Sunda clouded leopards on the small Batu Islands close to Sumatra.[1]

Between March and August 2005, tracks of clouded leopards were recorded during field research in the Tabin Wildlife Reserve in Sabah. The population size in the 56 km2 (22 sq mi) research area was estimated to be five individuals, based on a capture-recapture analysis of four confirmed animals differentiated by their tracks; with a density estimated at eight to 17 individuals per 100 km2 (39 sq mi). The population in Sabah is roughly estimated at 1,500–3,200 individuals, with only 275–585 of them living in totally protected reserves that are large enough to hold a long-term viable population of more than 50 individuals.[5]

The first documented film of a Sundaland clouded leopard was taken in June 2009 in Sabah.[6]

On Sumatra, Sunda clouded leopards occur most probably in much lower densities than on Borneo. One explanation for this lower density of about 1.29 individuals per 100 km2 (39 sq mi) might be that on Sumatra clouded leopards co-occur sympatric with the tiger, whereas on Borneo clouded leopards are the largest carnivores.[7]

Clouded leopard fossils have been found on

Ecology and behaviour

The habits of the Sunda clouded leopard are largely unknown because of the animal's secretive nature. It is assumed that it is generally a solitary creature.

The clouded leopard hunts mainly on the ground and uses its climbing skills to hide from dangers.[citation needed]

Evolutionary and taxonomic history

The genetic analysis of specimens of Neofelis nebulosa and Neofelis diardi implies that the two species diverged 1.4 million years ago, after having used a now submerged land bridge to reach Borneo and Sumatra from mainland Asia.[2]

The split of Neofelis diardi subspecies corresponds roughly with the catastrophic ‘‘super-

The species was named Felis diardi in honor of the

The species was long regarded as a subspecies of the clouded leopard, and named Neofelis nebulosa diardi. In December 2006, the journal

- Neofelis nebulosa from mainland Asia and

- Neofelis diardi from the Malay archipelago, except Peninsular Malaysia.

Results of a

Molecular, craniomandibular and dental analysis indicates subspecifical distinction of Bornean and Sumatran clouded leopards into two populations with separate evolutionary histories — a Bornean subspecies Neofelis diardi borneensis and a Sumatran subspecies Neofelis diardi diardi. Both populations are estimated to have diverged from each other during the Middle to Late Pleistocene.[9]

Threats

Sunda clouded leopards being strongly

Since the early 1970s, much of the forest cover has been cleared in southern Sumatra, in particular lowland

Borneo is one of the world’s areas with the highest deforestation rates. The island's rainforests are destructed rapidly due to large-scale conversion to plantations, illegal logging, and forest fires. While in the mid-1980s forests still covered nearly three quarters of the island, by 2005 only 52% of Borneo was still forested. Deforestation has been continuing at a highly unsustainable rate over the last twenty to thirty years. The impact the continuation of this trend will have is irreversible in terms of the effects on forest ecosystems, on the species that inhabit them, as well as on the people who live sustainably from and in the forests. The forests are used to feed the world’s hunger for timber and other non-timber products, while the land is used to feed the need for vegetable oils. Both forests and land make way for human settlement. Illegal trade in wildlife is a widely spread practice.[13]

Conservation

The species is listed on

Local names

The local names, "Macan Dahan" in Indonesian and "Harimau Dahan" in Malay (also reported historically in Sumatra), mean "tree branch tiger".[citation needed]

See also

- Carnivores discovered in the 2000s

References

- ^ a b c d e Template:IUCN2008

- ^ PMID 17141620.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 17141621.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ "New Species Declared: Clouded Leopard found on Borneo and Sumatra". ScienceDaily. 15 March 2007. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- PMID 17092347.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link - ^ Mohamed, A. and Wilting, A. (2009) Sundaland Clouded leopard Neofelis diardi. Filmed at Deramakot Forest Reserve, Sabah, Malaysia. Conservation of Carnivores in Sabah online

- ^ Hutujulu, B., Sunarto, Klenzendorf, S., Supriatna, J., Budiman, A. and Yahya, A. (2007) Study on the ecological characteristics of clouded leopard in Riau, Sumatra. In: J. Hughes and M. Mercer (eds) Felid Biology and Conservation: Programme and Abstracts : An International Conference, 17–20 September 2007, Oxford. Oxford University, Wildlife Conservation Research Unit

- ^ Meijaard, E. (2004) Biogeographic history of the javan leopard Panthera pardus based on a craniometric analysis. Journal of Mammalogy 85: 302–310.

- ^ doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.11.007.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Cuvier, G. (1823) Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles; ou, l'on retablit les caracteres de plusiers animaux dont les revolutions du globe ont detruit les especes. Volume IV: Les Ruminans et les Carnassiers Fossiles. Paris: G. Dufour & E. d'Ocagne

- ^ George Ripley (1858). The New American Cyclopedia. D. Appleton and Company. p. 543.

- ^ Gaveaua, David L.A., Wandonoc, H., Setiabudid, F. (2007). "Three decades of deforestation in southwest Sumatra: Have protected areas halted forest loss and logging, and promoted re-growth?" (PDF). Biological Conservation. 134 (4): 495–504.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rautner, M., Hardiono, M., Alfred, R. J. (2005), Borneo: treasure island at risk. Status of Forest, Wildlife, and related Threats on the Island of Borneo (PDF), WWF Germany

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

Older newspaper articles still online:

- The Clouded Leopard Project, March 2007: Borneo Clouded Leopard Classified as New Species

- BBC News, March 2007: Island leopard deemed new species

- msnbc.com, March 2007: New leopard species found in Borneo

- National Geographic, March 2007: Photo in the News: New Leopard Species Announced

- Daily Mail, March 2007: New species of leopard with largest fangs in cat world discovered