Water fluoridation: Difference between revisions

Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers 42,901 edits m Minor lowercase fix. |

204 million (66%) [2010 figures] included natural fluoridation | update dead link |

||

| Line 125: | Line 125: | ||

As of November 2012, a total of about 378 million people worldwide received artificially fluoridated water. The majority of those were in the United States. About 40 million worldwide received water that was naturally fluoridated to recommended levels.<ref name=extent/> |

As of November 2012, a total of about 378 million people worldwide received artificially fluoridated water. The majority of those were in the United States. About 40 million worldwide received water that was naturally fluoridated to recommended levels.<ref name=extent/> |

||

Much of the early work on establishing the connection between fluoride and dental health was performed by scientists in the USA during the early 20th century, and the USA was the first country to implement public water fluoridation on a wide scale.<ref name=Sellers>{{vcite journal |doi=10.1086/649401 |author=Sellers C |title=The artificial nature of fluoridated water: between nations, knowledge, and material flows |journal=Osiris |volume=19 |pages=182–200 |year=2004 |pmid=15478274 }}</ref> It has been introduced to varying degrees in many countries and territories outside the U.S., including Argentina, [[Water fluoridation in Australia|Australia]], Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Hong Kong, Ireland, Israel, Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, Spain, the UK, and Vietnam. |

Much of the early work on establishing the connection between fluoride and dental health was performed by scientists in the USA during the early 20th century, and the USA was the first country to implement public water fluoridation on a wide scale.<ref name=Sellers>{{vcite journal |doi=10.1086/649401 |author=Sellers C |title=The artificial nature of fluoridated water: between nations, knowledge, and material flows |journal=Osiris |volume=19 |pages=182–200 |year=2004 |pmid=15478274 }}</ref> It has been introduced to varying degrees in many countries and territories outside the U.S., including Argentina, [[Water fluoridation in Australia|Australia]], Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Hong Kong, Ireland, Israel, Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Serbia, Singapore, Spain, the UK, and Vietnam. In 2004, an estimated 13.7 million people in western Europe and 194 million in the U.S. received artificially fluoridated water.<ref name=extent/> |

||

Naturally fluoridated water is used in many countries, including Argentina, France, Gabon, Libya, Mexico, Senegal, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, the U.S., and Zimbabwe. In some locations, notably parts of Africa, China, and India, natural fluoridation exceeds recommended levels; in China an estimated 200 million people receive water fluoridated at or above recommended levels.<ref name=extent>{{vcite book |chapter=The extent of water fluoridation |chapterurl=http://bfsweb.org/onemillion/09%20One%20in%20a%20Million%20-%20The%20Extent%20of%20Fluoridation.pdf |url=http://bfsweb.org/onemillion/onemillion.htm |title=One in a Million: The facts about water fluoridation |edition=2nd |year=2004 |author=The British Fluoridation Society; The UK Public Health Association; The British Dental Association; The Faculty of Public Health |isbn=0-9547684-0-X |pages=55–80 |publisher=British Fluoridation Society |location=Manchester |chapterformat=PDF }}</ref> |

Naturally fluoridated water is used in many countries, including Argentina, France, Gabon, Libya, Mexico, Senegal, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, the U.S., and Zimbabwe. In some locations, notably parts of Africa, China, and India, natural fluoridation exceeds recommended levels; in China an estimated 200 million people receive water fluoridated at or above recommended levels.<ref name=extent>{{vcite book |chapter=The extent of water fluoridation |chapterurl=http://bfsweb.org/onemillion/09%20One%20in%20a%20Million%20-%20The%20Extent%20of%20Fluoridation.pdf |url=http://bfsweb.org/onemillion/onemillion.htm |title=One in a Million: The facts about water fluoridation |edition=2nd |year=2004 |author=The British Fluoridation Society; The UK Public Health Association; The British Dental Association; The Faculty of Public Health |isbn=0-9547684-0-X |pages=55–80 |publisher=British Fluoridation Society |location=Manchester |chapterformat=PDF }}</ref> |

||

Communities have discontinued water fluoridation in some countries, including Finland, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland.<ref name=Cheng2007/> On August 26, 2014, Israel officially stopped adding fluoride to its water supplies, stating "Only some 1% of the water is used for drinking, while 99% of the water is intended for other uses (industry, agriculture, flushing toilets etc.). There is also scientific evidence that fluoride in large amounts can lead to damage to health. When fluoride is supplied via drinking water, there is no control regarding the amount of fluoride actually consumed, which could lead to excessive consumption. Supply of fluoridated water forces those who do not so wish to also consume water with added fluoride. This approach is therefore not accepted in most countries in the world."<ref>Press Releases (August 17, 2014) [http://www.health.gov.il/English/News_and_Events/Spokespersons_Messages/Pages/17082014_1.aspx End of Mandatory Fluoridation in Israel], [[Ministry of Health (Israel)]] Retrieved September 29, 2014</ref><ref>Main, Douglas (August 29, 2014) [http://www.newsweek.com/israel-has-officially-banned-fluoridation-its-drinking-water-267411 Israel Has Officially Banned Fluoridation of Its Drinking Water], [[Newsweek]] Retrieved September 2, 2014</ref> This change was often motivated by political opposition to water fluoridation, but sometimes the need for water fluoridation was met by alternative strategies. The use of fluoride in its various forms is the foundation of tooth decay prevention throughout Europe; several countries have introduced fluoridated salt, with varying success: in Switzerland and Germany, fluoridated salt represents 65% to 70% of the domestic market, while in France the market share reached 60% in 1993 but dwindled to 14% in 2009; Spain, in 1986 the second West European country to introduce fluoridation of table salt, reported a market share in 2006 of only 10%. In three other West European countries, Greece, Austria and the Netherlands, the legal framework for production and marketing of fluoridated edible salt exists. At least six Central European countries (Hungary, the Czech and Slovak Republics, Croatia, Slovenia, Romania) have shown some interest in salt fluoridation; however, significant usage of approximately 35% was only achieved in the Czech Republic. The Slovak Republic had the equipment to treat salt by 2005; in the other four countries attempts to introduce fluoridated salt were not successful.<ref>{{cite web | title = Salt fluoridation in Europe and in Latin America – with potential worldwide | url = |

Communities have discontinued water fluoridation in some countries, including Finland, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland.<ref name=Cheng2007/> On August 26, 2014, Israel officially stopped adding fluoride to its water supplies, stating "Only some 1% of the water is used for drinking, while 99% of the water is intended for other uses (industry, agriculture, flushing toilets etc.). There is also scientific evidence that fluoride in large amounts can lead to damage to health. When fluoride is supplied via drinking water, there is no control regarding the amount of fluoride actually consumed, which could lead to excessive consumption. Supply of fluoridated water forces those who do not so wish to also consume water with added fluoride. This approach is therefore not accepted in most countries in the world."<ref>Press Releases (August 17, 2014) [http://www.health.gov.il/English/News_and_Events/Spokespersons_Messages/Pages/17082014_1.aspx End of Mandatory Fluoridation in Israel], [[Ministry of Health (Israel)]] Retrieved September 29, 2014</ref><ref>Main, Douglas (August 29, 2014) [http://www.newsweek.com/israel-has-officially-banned-fluoridation-its-drinking-water-267411 Israel Has Officially Banned Fluoridation of Its Drinking Water], [[Newsweek]] Retrieved September 2, 2014</ref> This change was often motivated by political opposition to water fluoridation, but sometimes the need for water fluoridation was met by alternative strategies. The use of fluoride in its various forms is the foundation of tooth decay prevention throughout Europe; several countries have introduced fluoridated salt, with varying success: in Switzerland and Germany, fluoridated salt represents 65% to 70% of the domestic market, while in France the market share reached 60% in 1993 but dwindled to 14% in 2009; Spain, in 1986 the second West European country to introduce fluoridation of table salt, reported a market share in 2006 of only 10%. In three other West European countries, Greece, Austria and the Netherlands, the legal framework for production and marketing of fluoridated edible salt exists. At least six Central European countries (Hungary, the Czech and Slovak Republics, Croatia, Slovenia, Romania) have shown some interest in salt fluoridation; however, significant usage of approximately 35% was only achieved in the Czech Republic. The Slovak Republic had the equipment to treat salt by 2005; in the other four countries attempts to introduce fluoridated salt were not successful.<ref>{{cite web |authors=Marthaler, T. M.; Gillespie, G. M.; Goetzfried, F.| title = Salt fluoridation in Europe and in Latin America – with potential worldwide | url = https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/cdhp-fluoridation/Marthaler+%282011%29+Salt+Fluoridation.pdf | publisher = Kali und Steinsalz Heft 3/2011 | accessdate = August 9, 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | title = Salt fluoridation in Central and Eastern Europe | url = http://www.sso.ch/doc/doc_download.cfm?uuid=9553209DD9D9424C4C98A160B35CD8DE&&IRACER_AUTOLINK&& | publisher = Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed, Vol 115: 8/2005 | accessdate = August 9, 2013}}</ref> |

||

== History == |

== History == |

||

Revision as of 16:55, 8 March 2015

Water fluoridation is the controlled addition of fluoride to a public water supply to reduce tooth decay. Fluoridated water has fluoride at a level that is effective for preventing cavities; this can occur naturally or by adding fluoride.[2] Fluoridated water operates on tooth surfaces: in the mouth it creates low levels of fluoride in saliva, which reduces the rate at which tooth enamel demineralizes and increases the rate at which it remineralizes in the early stages of cavities.[3] Typically a fluoridated compound is added to drinking water, a process that in the U.S. costs an average of about $1.32 per person-year.[2][4] Defluoridation is needed when the naturally occurring fluoride level exceeds recommended limits.[5] A 1994 World Health Organization expert committee suggested a level of fluoride from 0.5 to 1.0 mg/L (milligrams per litre), depending on climate.[6] Bottled water typically has unknown fluoride levels, and some domestic water filters remove some or all fluoride.[7]

Although fluoridation can cause dental fluorosis, which can alter the appearance of developing teeth or enamel fluorosis,[3] most of this is mild and usually not considered to be of aesthetic or public-health concern.[10] There is no clear evidence of other adverse effects from water fluoridation.[11] Studies on adverse effects have been mostly of low quality.[11] Fluoride's effects depend on the total daily intake of fluoride from all sources. Drinking water is typically the largest source;[12] other methods of fluoride therapy include fluoridation of toothpaste, salt, and milk.[13] Water fluoridation, when feasible and culturally acceptable, has substantial advantages, especially for subgroups at high risk.[8]

In 1999 the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention listed water fluoridation as one of the ten great public health achievements of the 20th century;[14] in contrast, most European countries have experienced substantial declines in tooth decay without its use, primarily due to the introduction of fluoride toothpaste in the 1970s.[3] Fluoridation may be more justified in the U.S. because of socioeconomic inequalities in dental health and dental care.[15] Public water fluoridation was first practiced in the U.S.,[16] and has been introduced to many other countries to varying degrees,[17] with many countries having water that is naturally fluoridated to recommended levels and others, such as in Europe, using fluoridated salts as an alternative source of fluoride.[18]

Goal

The goal of water fluoridation is to prevent tooth decay by adjusting the concentration of fluoride in public water supplies.

The goal of water fluoridation is to prevent a chronic disease whose burdens particularly fall on children and the poor.

Implementation

Fluoridation does not affect the appearance, taste, or smell of drinking water.[1] It is normally accomplished by adding one of three compounds to the water: sodium fluoride, fluorosilicic acid, or sodium fluorosilicate.

- Fluorosilicic acid (H2SiF6) is the most commonly used additive for water fluoridation in the United States.[34] It is an inexpensive liquid by-product of phosphate fertilizer manufacture.[31] It comes in varying strengths, typically 23–25%; because it contains so much water, shipping can be expensive.[32] It is also known as hexafluorosilicic, hexafluosilicic, hydrofluosilicic, and silicofluoric acid.[31]

- Sodium fluorosilicate (Na2SiF6) is the sodium salt of fluorosilicic acid. It is a powder or very fine crystal that is easier to ship than fluorosilicic acid. It is also known as sodium silicofluoride.[32]

These compounds were chosen for their solubility, safety, availability, and low cost.[31] A 1992 census found that, for U.S. public water supply systems reporting the type of compound used, 63% of the population received water fluoridated with fluorosilicic acid, 28% with sodium fluorosilicate, and 9% with sodium fluoride.[35] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention developed recommendations for water fluoridation that specify requirements for personnel, reporting, training, inspection, monitoring, surveillance, and actions in case of overfeed, along with technical requirements for each major compound used.[36]

Although fluoride was once considered an

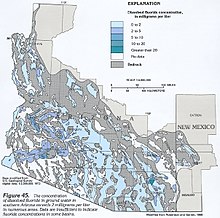

Fluoride naturally occurring in water can be above, at, or below recommended levels. Rivers and lakes generally contain fluoride levels less than 0.5 mg/L, but groundwater, particularly in volcanic or mountainous areas, can contain as much as 50 mg/L.

Mechanism

Fluoride exerts its major effect by interfering with the demineralization mechanism of tooth decay. Tooth decay is an

All fluoridation methods, including water fluoridation, create low levels of fluoride ions in saliva and plaque fluid, thus exerting a

Fluoride's effects depend on the total daily intake of fluoride from all sources.

Evidence

Existing evidence strongly suggests that water fluoridation reduces tooth decay. Consistent evidence also suggests that it causes dental fluorosis, most of which is mild and not usually of aesthetic concern.[10] No clear evidence of other adverse effects exists, though almost all research thereof has been of poor quality.[11]

Effectiveness

Water fluoridation effectively reduces cavities in both children and adults:[9] earlier studies showed that water fluoridation reduced childhood cavities by fifty to sixty percent, but more recent studies show lower reductions (18–40%) likely due to increasing use of fluoride from other sources, notably toothpaste, and also the 'halo effect' of food and drink that is made in fluoridated areas and consumed in unfluoridated ones.[2]

A 2000

Most countries in Europe have experienced substantial declines in cavities without the use of water fluoridation.[3] For example, in Finland and Germany, tooth decay rates remained stable or continued to decline after water fluoridation stopped. Fluoridation may be useful in the U.S. because unlike most European countries, the U.S. does not have school-based dental care, many children do not visit a dentist regularly, and for many U.S. children water fluoridation is the prime source of exposure to fluoride.[15] The effectiveness of water fluoridation can vary according to circumstances such as whether preventive dental care is free to all children.[56]

Some studies suggest that fluoridation reduces oral health

Fluorosis

Fluoride's adverse effects depend on total fluoride dosage from all sources. At the commonly recommended dosage, the only clear adverse effect is dental fluorosis, which can alter the appearance of children's teeth during tooth development; this is mostly mild and is unlikely to represent any real effect on aesthetic appearance or on public health.[10] The critical period of exposure is between ages one and four years, with the risk ending around age eight. Fluorosis can be prevented by monitoring all sources of fluoride, with fluoridated water directly or indirectly responsible for an estimated 40% of risk and other sources, notably toothpaste, responsible for the remaining 60%.[58] Compared to water naturally fluoridated at 0.4 mg/L, fluoridation to 1 mg/L is estimated to cause additional fluorosis in one of every 6 people (95% CI 4–21 people), and to cause additional fluorosis of aesthetic concern in one of every 22 people (95% CI 13.6–∞ people). Here, aesthetic concern is a term used in a standardized scale based on what adolescents would find unacceptable, as measured by a 1996 study of British 14-year-olds.[11] In many industrialized countries the prevalence of fluorosis is increasing even in unfluoridated communities, mostly because of fluoride from swallowed toothpaste.[51] A 2009 systematic review indicated that fluorosis is associated with consumption of infant formula or of water added to reconstitute the formula, that the evidence was distorted by publication bias, and that the evidence that the formula's fluoride caused the fluorosis was weak.[59] In the U.S. the decline in tooth decay was accompanied by increased fluorosis in both fluoridated and unfluoridated communities; accordingly, fluoride has been reduced in various ways worldwide in infant formulas, children's toothpaste, water, and fluoride-supplement schedules.[57]

Safety

Fluoridation has little effect on risk of

Fluoride can occur naturally in water in concentrations well above recommended levels, which can have

Like other common water additives such as

The effect of water fluoridation on the natural environment has been investigated, and no adverse effects have been established. Issues studied have included fluoride concentrations in groundwater and downstream rivers; lawns, gardens, and plants; consumption of plants grown in fluoridated water; air emissions; and equipment noise.[63]

Alternatives

Although water fluoridation is the most effective means of achieving fluoride exposure that is community-wide,

Fluoride

The effectiveness of

Milk fluoridation is practiced by the Borrow Foundation in some parts of Bulgaria, Chile, Peru, Russia, Macedonia, Thailand and the UK. Depending on location, the fluoride is added to milk, to powdered milk, or to yogurt. For example, milk-powder fluoridation is used in rural Chilean areas where water fluoridation is not technically feasible.[68] These programs are aimed at children, and have neither targeted nor been evaluated for adults.[13] A 2005 systematic review found insufficient evidence to support the practice, but also concluded that studies suggest that fluoridated milk benefits schoolchildren, especially their permanent teeth.[69]

Other public-health strategies to control tooth decay, such as education to change behavior and diet, have lacked impressive results.

A 2007 Australian review concluded that water fluoridation is the most effective and socially the most equitable way to expose entire communities to fluoride's cavity-prevention effects.[10] A 2002 U.S. review estimated that sealants decreased cavities by about 60% overall, compared to about 18–50% for fluoride.[55] A 2007 Italian review suggested that water fluoridation may not be needed, particularly in the industrialized countries where cavities have become rare, and concluded that toothpaste and other topical fluoride offers a best way to prevent cavities worldwide.[3] A 2004 World Health Organization review stated that water fluoridation, when it is culturally acceptable and technically feasible, has substantial advantages in preventing tooth decay, especially for subgroups at high risk.[8]

Economics

Fluoridation costs an estimated $1.32 per person-year on the average (range: $0.31–$13.94; all costs in this paragraph are for the U.S.[2] and are in 2024 dollars, inflation-adjusted from earlier estimates[4]). Larger water systems have lower per capita cost, and the cost is also affected by the number of fluoride injection points in the water system, the type of feeder and monitoring equipment, the fluoride chemical and its transportation and storage, and water plant personnel expertise.[2] In affluent countries the cost of salt fluoridation is also negligible; developing countries may find it prohibitively expensive to import the fluoride additive.[73] By comparison, fluoride toothpaste costs an estimated $11–$22 per person-year, with the incremental cost being zero for people who already brush their teeth for other reasons; and dental cleaning and application of fluoride varnish or gel costs an estimated $121 per person-year. Assuming the worst case, with the lowest estimated effectiveness and highest estimated operating costs for small cities, fluoridation costs an estimated $20–$31 per saved tooth-decay surface, which is lower than the estimated $119 to restore the surface[2] and the estimated $201 average discounted lifetime cost of the decayed surface, which includes the cost to maintain the restored tooth surface.[23] It is not known how much is spent in industrial countries to treat dental fluorosis, which is mostly due to fluoride from swallowed toothpaste.[51]

Although a 1989 workshop on

U.S. data from 1974 to 1992 indicate that when water fluoridation is introduced into a community, there are significant decreases in the number of employees per dental firm and the number of dental firms. The data suggest that some dentists respond to the demand shock by moving to non-fluoridated areas and by retraining as specialists.[74]

Ethics and politics

Like vaccination and food fortification, fluoridation pits the common good against individual rights.[26] Fluoridation can be viewed as a violation of ethical or legal rules that prohibit medical treatment without medical supervision or informed consent, and that prohibit administration of unlicensed medical substances.[3] It can also be viewed as a public health intervention, replicating the benefits of naturally fluoridated water, which can free people from the misery and expense of tooth decay and toothache, with the greatest benefit accruing to those least able to help themselves. This perspective suggests it would be unethical to withhold such treatment.[75]

National and international health agencies and dental associations throughout the world have endorsed water fluoridation as safe and effective.

Despite support by public health organizations and authorities, efforts to introduce water fluoridation have met considerable opposition. Anti-fluoridation arguments are "often based on Internet resources or books that present a highly misleading picture of water fluoridation".

Opponents of fluoridation include some researchers, dental and medical professionals, alternative medical practitioners such as

Use around the world

As of November 2012, a total of about 378 million people worldwide received artificially fluoridated water. The majority of those were in the United States. About 40 million worldwide received water that was naturally fluoridated to recommended levels.[18]

Much of the early work on establishing the connection between fluoride and dental health was performed by scientists in the USA during the early 20th century, and the USA was the first country to implement public water fluoridation on a wide scale.[16] It has been introduced to varying degrees in many countries and territories outside the U.S., including Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Hong Kong, Ireland, Israel, Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Serbia, Singapore, Spain, the UK, and Vietnam. In 2004, an estimated 13.7 million people in western Europe and 194 million in the U.S. received artificially fluoridated water.[18]

Naturally fluoridated water is used in many countries, including Argentina, France, Gabon, Libya, Mexico, Senegal, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, the U.S., and Zimbabwe. In some locations, notably parts of Africa, China, and India, natural fluoridation exceeds recommended levels; in China an estimated 200 million people receive water fluoridated at or above recommended levels.[18]

Communities have discontinued water fluoridation in some countries, including Finland, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland.[27] On August 26, 2014, Israel officially stopped adding fluoride to its water supplies, stating "Only some 1% of the water is used for drinking, while 99% of the water is intended for other uses (industry, agriculture, flushing toilets etc.). There is also scientific evidence that fluoride in large amounts can lead to damage to health. When fluoride is supplied via drinking water, there is no control regarding the amount of fluoride actually consumed, which could lead to excessive consumption. Supply of fluoridated water forces those who do not so wish to also consume water with added fluoride. This approach is therefore not accepted in most countries in the world."[99][100] This change was often motivated by political opposition to water fluoridation, but sometimes the need for water fluoridation was met by alternative strategies. The use of fluoride in its various forms is the foundation of tooth decay prevention throughout Europe; several countries have introduced fluoridated salt, with varying success: in Switzerland and Germany, fluoridated salt represents 65% to 70% of the domestic market, while in France the market share reached 60% in 1993 but dwindled to 14% in 2009; Spain, in 1986 the second West European country to introduce fluoridation of table salt, reported a market share in 2006 of only 10%. In three other West European countries, Greece, Austria and the Netherlands, the legal framework for production and marketing of fluoridated edible salt exists. At least six Central European countries (Hungary, the Czech and Slovak Republics, Croatia, Slovenia, Romania) have shown some interest in salt fluoridation; however, significant usage of approximately 35% was only achieved in the Czech Republic. The Slovak Republic had the equipment to treat salt by 2005; in the other four countries attempts to introduce fluoridated salt were not successful.[101][102]

History

The relationship between fluoride and teeth has been studied since the early 19th century. By 1850, investigators had established that fluoride occurs with varying concentrations in teeth, bone, and drinking water. By 1900, they had speculated that fluoride would protect against tooth decay, proposed supplementing the diet with fluoride, and observed mottled tooth enamel (now called dental fluorosis) without knowing the cause.[104]

The history of water fluoridation can be divided into three periods. The first (c. 1901–1933) was research into the cause of a form of mottled tooth enamel called the Colorado brown stain. The second (c. 1933–1945) focused on the relationship between fluoride concentrations, fluorosis, and tooth decay, and established that moderate levels of fluoride prevent cavities. The third period, from 1945 on, focused on adding fluoride to community water supplies.[30]

The foundation of water fluoridation in the U.S. was the research of the dentist Frederick McKay. McKay spent thirty years investigating the cause of what was then known as the Colorado brown stain, which produced mottled but also cavity-free teeth; with the help of

In the 1930s and early 1940s,

Fluoridation became an official policy of the

McKay's work had established that fluorosis occurred before tooth eruption. Dean and his colleagues assumed that fluoride's protection against cavities was also pre-eruptive, and this incorrect assumption was accepted for years. By 2000, however, the topical effects of fluoride (in both water and toothpaste) were better understood. The current dental position is that a constant low level of fluoride in the mouth works best to prevent cavities.[15]

References

- ^ PMID 9332806.

- ^ PMID 11521913.

- ^ PMID 17333303.

- ^ a b 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-59745-029-4. p. 293–315.

- ^ a b WHO Expert Committee on Oral Health Status and Fluoride Use. Fluorides and oral health [PDF]. 1994.

- ^ PMID 17485621.

- ^ PMID 15341615.

- ^ PMID 19772843.

- ^ PMID 18584000.

- ^ PMID 12047121.

- ^ ISBN 92-4-156319-2. Environmental occurrence, geochemistry and exposure. p. 5–27.

- ^ PMC 2626340.

- ^ PMID 10227303.

- ^ ISBN 0-19-515069-4. p. 307–22.

- ^ PMID 15478274.

- ^ a b Division of Oral Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC. Water fluoridation statistics for 2006; 2008-09-17 [Retrieved 2008-12-22].

- ^ ISBN 0-9547684-0-X. The extent of water fluoridation [PDF]. p. 55–80.

- ^ PMID 17208642.

- .

- .

- PMC 2147596.

- ^ PMID 11474918.

- ^ PMID 18630105.

- PMID 11014508.

- ^ a b

Ethics:

- McNally M, Downie J. The ethics of water fluoridation. J Can Dent Assoc. 2000;66(11):592–3. PMID 11253350.

- Cohen H, Locker D. The science and ethics of water fluoridation. J Can Dent Assoc. 2001;67(10):578–80. PMID 11737979.

- McNally M, Downie J. The ethics of water fluoridation. J Can Dent Assoc. 2000;66(11):592–3.

- ^ PMC 2001050.

- ^ PMC 2222595.

- ^ a b National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. The story of fluoridation; 2008-12-20 [Retrieved 2010-02-06].

- ^ PMID 8474047.

- ^ a b c d e Reeves TG. Centers for Disease Control. Water fluoridation: a manual for engineers and technicians [PDF]; 1986 [Retrieved 2008-12-10]. Cite error: The named reference "Reeves" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ ISBN 1-58321-311-2. History, theory, and chemicals. p. 1–14.

- ISBN 978-0-444-53086-8. p. 333–78.

- ^ "Water Fluoridation Additives Fact Sheet". cdc.gov. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ Division of Oral Health, National Center for Prevention Services, CDC. Fluoridation census 1992 [PDF]. 1993 [Retrieved 2008-12-29].

- PMID 7565542.

- PMID 1607439.

- ^ PMID 18614991.

- ^ U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. HHS and EPA announce new scientific assessments and actions on fluoride; 2011.

- .

- PMID 10728111.

- PMID 18200355.

- ^ PMID 18782377.

- ^ PMID 18694871.

- PMID 12097358.

- PMID 15153698.

- ISBN 978-0-8138-2416-1. p. 92–109.

- PMID 18694872.

- PMID 12586392.

- ^ ISBN 92-4-156319-2. Human health effects. p. 29–36.

- ^ PMID 11683551.

- ISBN 0-309-06350-7. Fluoride. p. 288–313.

- PMID 12914024.

- PMID 17891121.

- ^ PMID 12091093.

- PMID 11021844.

- ^ PMID 18694870.

- PMID 19179949.

- PMID 19571048.

- ISBN 92-4-156319-2. Guidelines and standards. p. 37–9.

- PMID 11579665.

- ^ Asheboro notifies residents of over-fluoridation of water. 2010-06-29. Fox 8.

- ^ PMID 15473093.

- PMC 1332668.

- ^ PMID 15897335.

- PMID 10884959.

- ^ PMC 2443131.

- ^ Bánóczy J, Rugg-Gunn AJ. Milk—a vehicle for fluorides: a review [PDF]. Rev Clin Pesq Odontol. 2006 [Retrieved 2009-01-03];2(5–6):415–26.

- PMID 16034911.

- PMID 18362315.

- PMID 18460675.

- PMID 20088215.

- PMID 16379137.

- ^ Ho K, Neidell M. Equilibrium effects of public goods: the impact of community water fluoridation on dentists [PDF]. 2009 [Retrieved 2009-10-13].

- ISBN 0-9547684-0-X. The ethics of water fluoridation [PDF]. p. 88–92.

- ^ ADA Council on Access, Prevention and Interprofessional Relations. American Dental Association. National and international organizations that recognize the public health benefits of community water fluoridation for preventing dental decay; 2005 [archived 2008-06-07; Retrieved 2008-12-22].

- ^ PMID 10714718.

- ^ Carmona RH. U.S. Public Health Service. Surgeon General's statement on community water fluoridation [PDF]; 2004-07-28 [Retrieved 2008-12-22].

- ^ American Public Health Association. Community water fluoridation in the United States; 2008 [Retrieved 2009-03-09].

- PMID 19772841.

- ^ Australian Dental Association. Community oral health promotion: fluoride use [PDF]; 2005 [Retrieved 2009-10-13].

- ^ Canadian Dental Association. CDA position on use of fluorides in caries prevention [PDF]; 2008 [Retrieved 2009-01-15].

- ^ ADA Council on Access, Prevention and Interprofessional Relations. American Dental Association. Fluoridation facts [PDF]; 2005 [archived 2008-07-23; Retrieved 2008-12-22].

- .

- PMID 18225698.

- ISBN 0-309-10128-X.

- ^ ISBN 0-19-515069-4. p. 323–42.

- ^ Libertarian Party. Consumer protection [Retrieved June 28, 2010].

- ISBN 978-0-470-44833-5. p. 62.

- ^ Nordlinger J. Water fights: believe it or not, the fluoridation war still rages—with a twist you may like. Natl Rev. 2003-06-30.

- ISBN 0-470-44833-4. Fluoride and health. p. 219–54.

- ^ PMID 18333872.

- PMID 19694932.

- PMID 10226722.

- PMID 19135693.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-470-44833-5. Fluorophobia. p. 127–69.

- PMID 9034969.

- ^ Press Releases (August 17, 2014) End of Mandatory Fluoridation in Israel, Ministry of Health (Israel) Retrieved September 29, 2014

- ^ Main, Douglas (August 29, 2014) Israel Has Officially Banned Fluoridation of Its Drinking Water, Newsweek Retrieved September 2, 2014

- ^ "Salt fluoridation in Europe and in Latin America – with potential worldwide" (PDF). Kali und Steinsalz Heft 3/2011. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "Salt fluoridation in Central and Eastern Europe". Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed, Vol 115: 8/2005. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- OCLC 5015927. p. 199.

- OCLC 14681626. p. 325–414.

- ^ Colorado brown stain:

- Peterson J. Solving the mystery of the Colorado Brown Stain. J Hist Dent. 1997;45(2):57–61. PMID 9468893.

- Colorado Springs Dental Society. The discovery of fluoride; 2004 [Retrieved 2012-06-11].

- Peterson J. Solving the mystery of the Colorado Brown Stain. J Hist Dent. 1997;45(2):57–61.

- ^ PMID 16215546.

- ^ PMC 2627472.

- PMID 14781280.

- PMID 19180863.

- PMID 15562942.

External links

- Fluoridation at Curlie