Typical antipsychotic

| Typical antipsychotic | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

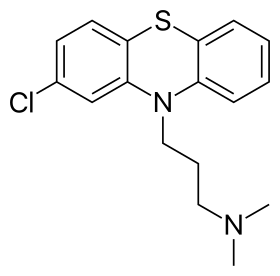

Skeletal formula of chlorpromazine, the first neuroleptic drug | |

| Synonyms | First generation antipsychotics, conventional antipsychotics, classical neuroleptics, traditional antipsychotics, major tranquilizers |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Typical antipsychotics (also known as major

Both generations of medication tend to block receptors in the brain's

Clinical uses

Typical antipsychotics block the dopamine 2 receptor (D2) receptor, causing a tranquilizing effect.[5] It is thought that 60–80% of D2 receptors need to be occupied for antipsychotic effect.[5] For reference, the typical antipsychotic haloperidol tends to block about 80% of D2 receptors at doses ranging from 2 to 5 mg per day.[5] On the aggregate level, no typical antipsychotic is more effective than any other, though people will vary in which antipsychotic they prefer to take based on individual differences in tolerability and effectiveness.[5] Typical antipsychotics can be used to treat, e.g., schizophrenia or severe agitation.[5] Haloperidol, due to the availability of a rapid-acting injectable formulation and decades of use, remains the most commonly used antipsychotic for treating severe agitation in the emergency department setting.[5]

Adverse effects

Adverse effects vary among the various agents in this class of medications, but common effects include: dry mouth,

There is a risk of developing a serious condition called tardive dyskinesia as a side effect of antipsychotics, including typical antipsychotics. The risk of developing tardive dyskinesia after chronic typical antipsychotic usage varies on several factors, such as age and gender, as well as the specific antipsychotic used. The commonly reported incidence of TD among younger patients is about 5% per year. Among older patients incidence rates as high as 20% per year have been reported. The average prevalence is approximately 30%.[7] There are few treatments that have consistently been shown to be effective for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia, though an VMAT2 inhibitor like valbenazine may help.[8] The atypical antipsychotic clozapine has also been suggested as an alternative antipsychotic for patients experiencing tardive dyskinesia.[9] Tardive dyskinesia may reverse upon discontinuation of the offending agent or it may be irreversible, withdrawal may also make tardive dyskinesia more severe.[10]

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is a rare, but potentially fatal side effect of antipsychotic treatment. NMS is characterized by fever, muscle rigidity, autonomic dysfunction, and altered mental status. Treatment includes discontinuation of the offending agent and supportive care.

The role of typical antipsychotics has come into question recently as studies have suggested that typical antipsychotics may increase the risk of death in elderly patients. A 2005 retrospective cohort study from the New England Journal of Medicine showed an increase in risk of death with the use of typical antipsychotics that was on par with the increase shown with atypical antipsychotics.[11] This has led some to question the common use of antipsychotics for the treatment of agitation in the elderly, particularly with the availability of alternatives such as mood stabilizing and antiepileptic drugs.

Potency

Traditional antipsychotics are classified as high-potency, mid-potency, or low-potency based on their potency for the D2 receptor:

| Potency | Examples | Adverse effect profile |

| high | fluphenazine and haloperidol | more dry mouth )

|

| middle | perphenazine and loxapine | intermediate D2 affinity, with more off-target effects than high-potency agents |

| low | chlorpromazine | less risk of EPS but more antihistaminic effects, alpha adrenergic antagonism, and anticholinergic effects |

Prochlorperazine (Compazine, Buccastem, Stemetil) and Pimozide (Orap) are less commonly used to treat psychotic states, and so are sometimes excluded from this classification.[12]

A related concept to D2 potency is the concept of "chlorpromazine equivalence", which provides a measure of the relative effectiveness of antipsychotics.[13][14] The measure specifies the amount (mass) in milligrams of a given drug that must be administered in order to achieve desired effects equivalent to those of 100 milligrams of chlorpromazine.[15] Another method is "defined daily dose" (DDD), which is the assumed average dose of an antipsychotic that an adult would receive during long-term treatment.[15] DDD is primarily used for comparing the utilization of antipsychotics (e.g. in an insurance claim database), rather than comparing therapeutic effects between antipsychotics.[15] Maximum dose methods are sometimes used to compare between antipsychotics as well.[15] It is important to note that these methods do not generally account for differences between the tolerability (i.e. the risk of side effects) or the safety between medications.[15]

For a list of typical antipsychotics organized by potency, see below:

Low potency

- Chlorpromazine

- Chlorprothixene

- Levomepromazine

- Mesoridazine

- Periciazine

- Promazine

- Thioridazine† (withdrawn by brand-name manufacturer and most countries)

Medium potency

- Loxapine

- Molindone

- Perphenazine

- Thiothixene

High potency

- Droperidol

- Flupentixol

- Fluphenazine

- Haloperidol

- Pimozide

- Prochlorperazine

- Thioproperazine

- Trifluoperazine

- Zuclopenthixol

Where: † indicates products that have since been discontinued.[16]

Long-acting injectables

Some typical antipsychotics have been formulated as a long-acting injectable (LAI), or "depot", formulation. Depot injections are also used on persons under involuntary commitment to force compliance with a court treatment order when the person would refuse to take daily oral medication. This has the effect of dosing a person who doesn't consent to take the drug. The United Nations Special Rapporteur On Torture has classified this as a human rights violation and cruel or inhuman treatment.[17]

The first LAI antipsychotics (often referred to as simply "LAIs") were the typical antipsychotics fluphenazine and haloperidol.

Both of the typical antipsychotic LAIs are inexpensive in comparison to the atypical LAIs.[18] Doctors usually prefer atypical LAIs over typical LAIs due to the differences in adverse effects between typical and atypical antipsychotics in general.[19]

| Medication | Brand name | Class | Vehicle | Dosage | Tmax | t1/2 single | t1/2 multiple | logPc | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aripiprazole lauroxil | Aristada | Atypical | Watera | 441–1064 mg/4–8 weeks | 24–35 days | ? | 54–57 days | 7.9–10.0 | |

Aripiprazole monohydrate |

Abilify Maintena | Atypical | Watera | 300–400 mg/4 weeks | 7 days | ? | 30–47 days | 4.9–5.2 | |

| Bromperidol decanoate | Impromen Decanoas | Typical | Sesame oil | 40–300 mg/4 weeks | 3–9 days | ? | 21–25 days | 7.9 | [20] |

Clopentixol decanoate |

Sordinol Depot | Typical | Viscoleob | 50–600 mg/1–4 weeks | 4–7 days | ? | 19 days | 9.0 | [21] |

Flupentixol decanoate |

Depixol | Typical | Viscoleob | 10–200 mg/2–4 weeks | 4–10 days | 8 days | 17 days | 7.2–9.2 | [21][22] |

Fluphenazine decanoate |

Prolixin Decanoate | Typical | Sesame oil | 12.5–100 mg/2–5 weeks | 1–2 days | 1–10 days | 14–100 days | 7.2–9.0 | [23][24][25] |

Fluphenazine enanthate |

Prolixin Enanthate | Typical | Sesame oil | 12.5–100 mg/1–4 weeks | 2–3 days | 4 days | ? | 6.4–7.4 | [24] |

| Fluspirilene | Imap, Redeptin | Typical | Watera | 2–12 mg/1 week | 1–8 days | 7 days | ? | 5.2–5.8 | [26] |

| Haloperidol decanoate | Haldol Decanoate | Typical | Sesame oil | 20–400 mg/2–4 weeks | 3–9 days | 18–21 days | 7.2–7.9 | [27][28] | |

Olanzapine pamoate |

Zyprexa Relprevv | Atypical | Watera | 150–405 mg/2–4 weeks | 7 days | ? | 30 days | – | |

| Oxyprothepin decanoate | Meclopin | Typical | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | 8.5–8.7 | |

Paliperidone palmitate |

Invega Sustenna | Atypical | Watera | 39–819 mg/4–12 weeks | 13–33 days | 25–139 days | ? | 8.1–10.1 | |

Perphenazine decanoate |

Trilafon Dekanoat | Typical | Sesame oil | 50–200 mg/2–4 weeks | ? | ? | 27 days | 8.9 | |

| Perphenazine enanthate | Trilafon Enanthate | Typical | Sesame oil | 25–200 mg/2 weeks | 2–3 days | ? | 4–7 days | 6.4–7.2 | [29] |

Pipotiazine palmitate |

Piportil Longum | Typical | Viscoleob | 25–400 mg/4 weeks | 9–10 days | ? | 14–21 days | 8.5–11.6 | [22] |

Pipotiazine undecylenate |

Piportil Medium | Typical | Sesame oil | 100–200 mg/2 weeks | ? | ? | ? | 8.4 | |

| Risperidone | Risperdal Consta | Atypical | Microspheres |

12.5–75 mg/2 weeks | 21 days | ? | 3–6 days | – | |

Zuclopentixol acetate |

Clopixol Acuphase | Typical | Viscoleob | 50–200 mg/1–3 days | 1–2 days | 1–2 days | 4.7–4.9 | ||

Zuclopentixol decanoate |

Clopixol Depot | Typical | Viscoleob | 50–800 mg/2–4 weeks | 4–9 days | ? | 11–21 days | 7.5–9.0 | |

| Note: All by . Sources: Main: See template. | |||||||||

History

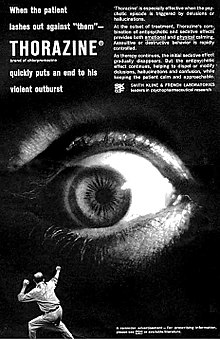

The original antipsychotic drugs were happened upon largely by chance and then tested for their effectiveness. The first, chlorpromazine, was developed as a surgical anesthetic after an initial report in 1952.[5] It was first used in psychiatric institutions because of its powerful tranquilizing effect; at the time it was advertised as a "pharmacological lobotomy".[31] (Note that "tranquilizing" here only refers to changes in external behavior, while the experience a person has internally may be one of increased agitation but inability to express it.)[32]

Until the 1970s there was considerable debate within psychiatry on the most appropriate term to use to describe the new drugs.

See also

- Tranquilizer

- Atypical antipsychotic

- Tardive dyskinesia

- Schizophrenia

- Bipolar disorder

- Psychiatric survivors' movement

References

- PMID 10579370.

- PMID 18185824.

- S2CID 19951248. Archived from the originalon 2023-02-06. Retrieved 2023-03-02.

- ^ "Not found". www.rcpsych.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-61537-230-0.

- PMID 2870650.

- S2CID 40761404.

- ^ Office of the Commissioner (24 March 2020). "FDA approves first drug to treat tardive dyskinesia". FDA. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- S2CID 198912192.

- ^ "Tardive dyskinesia: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". Archived from the original on 2017-01-31. Retrieved 2017-01-18.[full citation needed]

- S2CID 35202051.

- ISBN 0-684-82737-9.

- PMID 12823080.

- S2CID 12939895.

- ^ S2CID 45642900.

- ^ Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ "Special rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment" (PDF). Retrieved 2024-02-07.

- ^ a b c d e f Kennedy WK (2012). "When and how to use long-acting injectable antipsychotics". Current Psychiatry. 11 (8): 40–43.

- ^ a b c d Carpenter J, Wong KK (2018). "Long-acting injectable antipsychotics: What to do about missed doses". Current Psychiatry. 17 (7): 10–12, 14–19, 56.

- ^ Parent M, Toussaint C, Gilson H (1983). "Long-term treatment of chronic psychotics with bromperidol decanoate: clinical and pharmacokinetic evaluation". Current Therapeutic Research. 34 (1): 1–6.

- ^ PMID 6931472.

- ^ a b Reynolds JE (1993). "Anxiolytic sedatives, hypnotics and neuroleptics.". Martindale: The Extra Pharmacopoeia (30th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. pp. 364–623.

- PMID 6143748.

- ^ PMID 444352.

- ^ Young D, Ereshefsky L, Saklad SR, Jann MW, Garcia N (1984). Explaining the pharmacokinetics of fluphenazine through computer simulations. (Abstract.). 19th Annual Midyear Clinical Meeting of the American Society of Hospital Pharmacists. Dallas, Texas.

- PMID 4992598.

- PMID 3545764.

- PMID 7185768.

- ^ Larsson M, Axelsson R, Forsman A (1984). "On the pharmacokinetics of perphenazine: a clinical study of perphenazine enanthate and decanoate". Current Therapeutic Research. 36 (6): 1071–88.

- ^ The text reads: "When the patient lashes out against 'them' - THORAZINE (brand of chlorpromazine) quickly puts an end to his violent outburst. 'Thorazine' is especially effective when the psychotic episode is triggered by delusions or hallucinations. At the outset of treatment, Thorazine's combination of antipsychotic and sedative effects provides both emotional and physical calming. Assaultive or destructive behavior is rapidly controlled. As therapy continues, the initial sedative effect gradually disappears. But the antipsychotic effect continues, helping to dispel or modify delusions, hallucinations and confusion, while keeping the patient calm and approachable. SMITH KLINE AND FRENCH LABORATORIES leaders in psychopharmaceutical research."

- ^ from the original on 9 July 2017.

- ^ Muench, John (1 March 2010). "Adverse Effects Of Antipsychotics". American Family Physician. 81 (5): 617–622. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ PMID 12066446.