Uniform tiling

In

Uniform tilings can exist in both the

Most uniform tilings can be made from a Wythoff construction starting with a symmetry group and a singular generator point inside of the fundamental domain. A planar symmetry group has a polygonal fundamental domain and can be represented by its group notation: the sequence of the reflection orders of the fundamental domain vertices.

A fundamental domain triangle is denoted (p q r), where p, q, r are whole numbers > 1, i.e. ≥ 2; a fundamental domain right triangle is denoted (p q 2). The triangle may exist as a

There are several symbolic schemes for denoting these figures:

- The modified Schläfli symbol for a right triangle domain: (p q 2) → {p, q}.

- The Coxeter-Dynkin diagramis a triangular graph with p, q, r labeled on the edges. If r = 2, then the graph is linear, since diagram nodes with connectivity 2 are not connected to each other by a diagram branch (since domain mirrors meeting at 90 degrees generate no new mirrors).

- The Wythoff symbol takes the three integers and separates them by a vertical bar (|). If the generator point is off the mirror opposite to a domain vertex, then the reflection order of this domain vertex is given before the bar.

- Finally, a uniform tiling can be described by its vertex configuration: the (identical) sequence of polygons around each (equivalent) vertex.

All uniform tilings can be constructed from various operations applied to

Coxeter groups

For groups with integer reflection orders, including:

| Orbifold symmetry |

Coxeter group | Coxeter

diagram |

Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compact | |||||

| *333 | (3 3 3) | [3[3]] | 3 reflective forms, 1 snub | ||

| *442 | (4 4 2) | [4,4] | 5 reflective forms, 1 snub | ||

| *632 | (6 3 2) | [6,3] | 7 reflective forms, 1 snub | ||

| *2222 | (∞ 2 ∞ 2) | × | [∞,2,∞] | 3 reflective forms, 1 snub | |

| Noncompact (Frieze) | |||||

| *∞∞ | (∞) | [∞] | |||

| *22∞ | (2 2 ∞) | × | [∞,2] | 2 reflective forms, 1 snub | |

| Orbifold symmetry |

Coxeter group | Coxeter

diagram |

Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compact | ||||

| *pq2 | (p q 2) | [p,q] | 2(p+q) < pq | |

| *pqr | (p q r) | [(p,q,r)] | pq+pr+qr < pqr, i.e. 1/p + 1/q + 1/r < 1 | |

| Paracompact | ||||

| *∞p2 | (p ∞ 2) | [p,∞] | p ≥ 3 | |

| *∞pq | (p q ∞) | [(p,q,∞)] | p,q ≥ 3; p+q > 6 | |

| *∞∞p | (p ∞ ∞) | [(p,∞,∞)] | p ≥ 3 | |

| *∞∞∞ | (∞ ∞ ∞) | [(∞,∞,∞)] | ||

Uniform tilings of the Euclidean plane

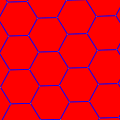

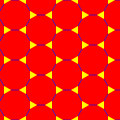

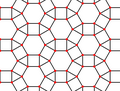

There are symmetry groups on the Euclidean plane constructed from fundamental triangles: (4 4 2), (6 3 2), and (3 3 3). Each is represented by a set of lines of reflection that divide the plane into fundamental triangles.

These symmetry groups create 3

A prismatic symmetry group, (2 2 2 2), is represented by two sets of parallel mirrors, which in general can make a rectangular fundamental domain. It generates no new tilings.

A further prismatic symmetry group, (∞ 2 2), has an infinite fundamental domain. It constructs two uniform tilings: the apeirogonal prism and apeirogonal antiprism.

The stacking of the finite faces of these two prismatic tilings constructs one

Right angle fundamental triangles: (p q 2)

| (p q 2) | Fund. triangles |

Parent | Truncated | Rectified | Bitruncated | Birectified (dual) |

Cantellated | Omnitruncated (Cantitruncated) |

Snub |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wythoff symbol | q | p 2 | 2 q | p | 2 | p q | 2 p | q | p | q 2 | p q | 2 | p q 2 | | | p q 2 | |

| Schläfli symbol | {p,q} | t{p,q} | r{p,q} | 2t{p,q}=t{q,p} | 2r{p,q}={q,p} | rr{p,q} | tr{p,q} | sr{p,q} | |

Coxeter diagram

|

|||||||||

| Vertex config. | pq | q.2p.2p | (p.q)2 | p.2q.2q | qp | p.4.q.4 | 4.2p.2q | 3.3.p.3.q | |

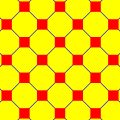

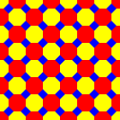

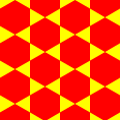

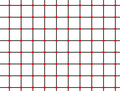

| Square tiling (4 4 2) |

|

{4,4} |

4.8.8 |

4.4.4.4 |

4.8.8 |

{4,4} |

4.4.4.4 |

4.8.8 |

3.3.4.3.4 |

| Hexagonal tiling (6 3 2) |

|

{6,3} |

3.12.12 |

3.6.3.6 |

6.6.6 |

{3,6} |

3.4.6.4

|

4.6.12

|

3.3.3.3.6

|

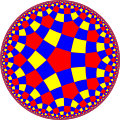

General fundamental triangles: (p q r)

| Wythoff symbol (p q r) |

Fund. triangles |

q | p r | r q | p | r | p q | r p | q | p | q r | p q | r | p q r | | | p q r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Coxeter diagram

|

|||||||||

| Vertex config. | (p.q)r | r.2p.q.2p | (p.r)q | q.2r.p.2r | (q.r)p | q.2r.p.2r | r.2q.p.2q | 3.r.3.q.3.p | |

| Triangular (3 3 3) |

|

(3.3)3 |

3.6.3.6 |

(3.3)3 |

3.6.3.6 |

(3.3)3 |

3.6.3.6 |

6.6.6 |

3.3.3.3.3.3 |

Non-simplical fundamental domains

The only possible fundamental domain in Euclidean 2-space that is not a

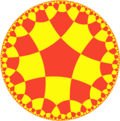

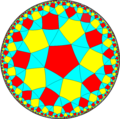

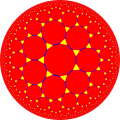

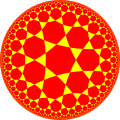

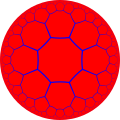

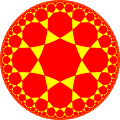

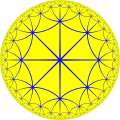

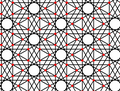

Uniform tilings of the hyperbolic plane

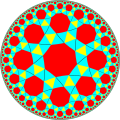

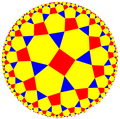

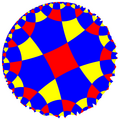

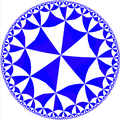

There are infinitely many uniform tilings by convex regular polygons on the hyperbolic plane, each based on a different reflective symmetry group (p q r).

A sampling is shown here with a Poincaré disk projection.

The

Further symmetry groups exist in the hyperbolic plane with quadrilateral fundamental domains — starting with (2 2 2 3), etc. — that can generate new forms. As well, there are fundamental domains that place vertices at infinity, such as (∞ 2 3), etc.

Right angle fundamental triangles: (p q 2)

| (p q 2) | Fund. triangles |

Parent | Truncated | Rectified | Bitruncated | Birectified (dual) |

Cantellated | Omnitruncated (Cantitruncated) |

Snub |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wythoff symbol | q | p 2 | 2 q | p | 2 | p q | 2 p | q | p | q 2 | p q | 2 | p q 2 | | | p q 2 | |

| Schläfli symbol | t{p,q} | t{p,q} | r{p,q} | 2t{p,q}=t{q,p} | 2r{p,q}={q,p} | rr{p,q} | tr{p,q} | sr{p,q} | |

Coxeter diagram

|

|||||||||

| Vertex config. | pq | q.2p.2p | p.q.p.q | p.2q.2q | qp | p.4.q.4 | 4.2p.2q | 3.3.p.3.q | |

| (5 4 2) |  V4.8.10 |

{5,4} |

4.10.10 |

4.5.4.5 |

5.8.8 |

{4,5} |

4.4.5.4 |

4.8.10 |

3.3.4.3.5 |

| (5 5 2) |  V4.10.10 |

{5,5} |

5.10.10 |

5.5.5.5 |

5.10.10 |

{5,5} |

5.4.5.4 |

4.10.10 |

3.3.5.3.5 |

| (7 3 2) |  V4.6.14 |

{7,3}

|

3.14.14 |

3.7.3.7 |

7.6.6 |

{3,7} |

3.4.7.4 |

4.6.14

|

3.3.3.3.7 |

| (8 3 2) |  V4.6.16 |

{8,3} |

3.16.16 |

3.8.3.8 |

8.6.6 |

{3,8} |

3.4.8.4 |

4.6.16

|

3.3.3.3.8 |

General fundamental triangles: (p q r)

| Wythoff symbol (p q r) |

Fund. triangles |

q | p r | r q | p | r | p q | r p | q | p | q r | p q | r | p q r | | | p q r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Coxeter diagram

|

|||||||||

| Vertex config. | (p.r)q | r.2p.q.2p | (p.q)r | q.2r.p.2r | (q.r)p | r.2q.p.2q | 2p.2q.2r | 3.r.3.q.3.p | |

| (4 3 3) |  V6.6.8 |

(3.4)3 |

3.8.3.8 |

(3.4)3 |

3.6.4.6 |

(3.3)4 |

3.6.4.6 |

6.6.8 |

3.3.3.3.3.4 |

| (4 4 3) |  V6.8.8 |

(3.4)4 |

3.8.4.8 |

(4.4)3 |

3.6.4.6 |

(3.4)4 |

4.6.4.6 |

6.8.8 |

3.3.3.4.3.4 |

| (4 4 4) |  V8.8.8 |

(4.4)4 |

4.8.4.8 |

(4.4)4 |

4.8.4.8 |

(4.4)4 |

4.8.4.8 |

8.8.8 |

3.4.3.4.3.4 |

Expanded lists of uniform tilings

There are several ways the list of uniform tilings can be expanded:

- Vertex figures can have retrograde faces and turn around the vertex more than once.

- Star polygon tiles can be included.

- Apeirogons, {∞}, can be used as tiling faces.

- Zigzags (apeirogons alternating between two angles) can also be used.

- The restriction that tiles meet edge-to-edge can be relaxed, allowing additional tilings such as the Pythagorean tiling.

Symmetry group triangles with retrogrades include:

- (4/3 4/3 2), (6 3/2 2), (6/5 3 2), (6 6/5 3), (6 6 3/2).

Symmetry group triangles with infinity include:

- (4 4/3 ∞), (3/2 3 ∞), (6 6/5 ∞), (3 3/2 ∞).

Branko Grünbaum and G. C. Shephard, in the 1987 book Tilings and patterns, section 12.3, enumerate a list of 25 uniform tilings, including the 11 convex forms, and add 14 more they call hollow tilings, using the first two expansions above: star polygon faces and generalized vertex figures.[1]

In 1981, Grünbaum, Miller, and Shephard, in their paper Uniform Tilings with Hollow Tiles, list 25 tilings using the first two expansions and 28 more when the third is added (making 53 using Coxeter et al.'s definition). When the fourth is added, they list an additional 23 uniform tilings and 10 families (8 depending on continuous parameters and 2 on discrete parameters).[2]

Besides the 11 convex solutions, the 28 uniform star tilings listed by Coxeter et al., grouped by shared edge graphs, are shown below, followed by 15 more listed by Grünbaum et al. that meet Coxeter et al.'s definition but were missed by them.

This set is not proved complete. By "2.25" is meant tiling 25 in Grünbaum et al.'s table 2 from 1981.

The following three tilings are exceptional in that there is only finitely many of one face type: two apeirogons in each. Sometimes the order-2 apeirogonal tiling is not included, as its two faces meet at more than one edge.

| McNeill[3] | Diagram | Vertex Config. |

Wythoff | Symmetry | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | ∞.∞ | p1m1 | (Two half-plane tiles, order-2 apeirogonal tiling) | ||

| I2 | 4.4.∞ | ∞ 2 | 2 | p1m1 | Apeirogonal prism | |

| I3 | 3.3.3.∞ | | 2 2 ∞ | p11g | Apeirogonal antiprism |

For clarity, the tilings are not colored from here onward (due to the overlaps). A set of polygons around one vertex is highlighted. McNeill only lists tilings given by Coxeter et al. (1954). The eleven convex uniform tilings have been repeated for reference.

| Wallpaper group symmetry | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McNeill[3] | Grünbaum et al., 1981[2] | Edge diagram |

Highlighted | Vertex Config. |

Wythoff | Symmetry |

| Convex | 1.9 |  |

|

4.4.4.4 | 4 | 2 4 | p4m |

| I4 | 2.14 |  |

4.∞.4/3.∞ 4.∞.−4.∞ |

4/3 4 | ∞ | p4m | |

| Convex | 1.24 |  |

6.6.6 | 3 | 2 6 | p6m | |

| Convex | 1.25 |  |

|

3.3.3.3.3.3 | 6 | 2 3 | p6m |

| I5 | 2.26 |  |

(3.∞.3.∞.3.∞)/2 | 3/2 | 3 ∞ | p3m1 | |

| Convex | 1.23 |  |

|

3.6.3.6 | 2 | 3 6 | p6m |

| I6 | 2.25 |  |

6.∞.6/5.∞ 6.∞.−6.∞ |

6/5 6 | ∞ | p6m | |

| I7 | 2.24 |  |

∞.3.∞.3/2 3.∞.−3.∞ |

3/2 3 | ∞ | p6m | |

| Convex | 1.14 |  |

|

3.4.6.4 | 3 6 | 2 | p6m |

| 1 | 1.15 |

|

3/2.12.6.12 −3.12.6.12 |

3/2 6 | 6 | p6m | |

| 1.16 |  |

4.12.4/3.12/11 4.12.−4.−12 |

2 6 (3/2 6/2) | | p6m | ||

| Convex | 1.5 |  |

4.8.8 | 2 4 | 4 | p4m | |

| 2 | 2.7 |  |

|

4.8/3.∞.8/3 | 4 ∞ | 4/3 | p4m |

| 1.7 |  |

8/3.8.8/5.8/7 8.8/3.−8.−8/3 |

4/3 4 (4/2 ∞/2) | | p4m | ||

| 2.6 |  |

8.4/3.8.∞ −4.8.∞.8 |

4/3 ∞ | 4 | p4m | ||

| Convex | 1.20 |  |

3.12.12 | 2 3 | 6 | p6m | |

| 3 | 2.17 |  |

|

6.12/5.∞.12/5 | 6 ∞ | 6/5 | p6m |

| 1.21 |  |

12/5.12.12/7.12/11 12.12/5.−12.−12/5 |

6/5 6 (6/2 ∞/2) | | p6m | ||

| 2.16 |  |

12.6/5.12.∞ −6.12.∞.12 |

6/5 ∞ | 6 | p6m | ||

| 4 | 1.18 |  |

|

12/5.3.12/5.6/5 3.12/5.−6.12/5 |

3 6 | 6/5 | p6m |

| 1.19 |  |

12/5.4.12/7.4/3 4.12/5.-4.-12/5 |

2 6/5 (3/2 6/2) | | p6m | ||

| 1.17 |  |

4.3/2.4.6/5 3.−4.6.−4 |

3/2 6 | 2 | p6m | ||

| 5 | 2.5 |  |

|

8.8/3.∞ | 4/3 4 ∞ | | p4m |

| 6 | 2.15 |  |

|

12.12/5.∞ | 6/5 6 ∞ | | p6m |

| 7 | 1.6 |  |

|

8.4/3.8/5 4.−8.8/3 |

2 4/3 4 | | p4m |

| Convex | 1.11 |  |

4.6.12 | 2 3 6 | | p6m | |

| 8 | 1.13 |  |

|

6.4/3.12/7 4.−6.12/5 |

2 3 6/5 | | p6m |

| 9 | 1.12 |  |

|

12.6/5.12/7 6.−12.12/5 |

3 6/5 6 | | p6m |

| 10 | 1.8 |  |

|

4.8/5.8/5 −4.8/3.8/3 |

2 4 | 4/3 | p4m |

| 11 | 1.22 |  |

|

12/5.12/5.3/2 −3.12/5.12/5 |

2 3 | 6/5 | p6m |

| Convex | 1.1 |  |

3.3.3.4.4 | non-Wythoffian |

cmm | |

| 12 | 1.2 |  |

|

4.4.3/2.3/2.3/2 3.3.3.−4.−4 |

non-Wythoffian | cmm |

| Convex | 1.3 |  |

3.3.4.3.4 | | 2 4 4 | p4g | |

| 13 | 1.4 |  |

4.3/2.4.3/2.3/2 3.3.−4.3.−4 |

| 2 4/3 4/3 | p4g | |

| 14 | 2.4 |  |

3.4.3.4/3.3.∞ 3.4.3.−4.3.∞ |

| 4/3 4 ∞ | p4 | |

| Convex | 1.10 |  |

3.3.3.3.6 | | 2 3 6 | p6 | |

| 2.1 |  |

3/2.∞.3/2.∞.3/2.4/3.4/3 3.4.4.3.∞.3.∞ |

non-Wythoffian | cmm | ||

| 2.2 |  |

3/2.∞.3/2.∞.3/2.4.4 3.−4.−4.3.∞.3.∞ |

non-Wythoffian | cmm | ||

| 2.3 |  |

3/2.∞.3/2.4.4.3/2.4/3.4/3 3.4.4.3.−4.−4.3.∞ |

non-Wythoffian | p3 | ||

| 2.8 |  |

4.∞.4/3.8/3.8 4.8.8/3.−4.∞ |

non-Wythoffian | p4m | ||

| 2.9 |  |

4.∞.4.8.8/3 −4.8.8/3.4.∞ |

non-Wythoffian | p4m | ||

| 2.10 |  |

4.∞.4/3.8.4/3.8 4.8.−4.8.−4.∞ |

non-Wythoffian | p4m | ||

| 2.11 |  |

4.∞.4/3.8.4/3.8 4.8.−4.8.−4.∞ |

non-Wythoffian | p4g | ||

| 2.12 |  |

4.∞.4/3.8/3.4.8/3 4.8/3.4.8/3.−4.∞ |

non-Wythoffian | p4m | ||

| 2.13 |  |

4.∞.4/3.8/3.4.8/3 4.8/3.4.8/3.−4.∞ |

non-Wythoffian | p4g | ||

| 2.18 |  |

3/2.∞.3/2.4/3.4/3.3/2.4/3.4/3 3.4.4.3.4.4.3.∞ |

non-Wythoffian | p6m | ||

| 2.19 |  |

3/2.∞.3/2.4.4.3/2.4.4 3.−4.−4.3.-4.−4.3.∞ |

non-Wythoffian | p6m | ||

| 2.20 |  |

3/2.∞.3/2.∞.3/2.12/11.6.12/11 3.12.−6.12.3.∞.3.∞ |

non-Wythoffian | p6m | ||

| 2.21 |  |

3/2.∞.3/2.∞.3/2.12.6/5.12 3.−12.6.−12.3.∞.3.∞ |

non-Wythoffian | p6m | ||

| 2.22 |  |

3/2.∞.3/2.∞.3/2.12/7.6/5.12/7 3.12/5.6.12/5.3.∞.3.∞ |

non-Wythoffian | p6m | ||

| 2.23 |  |

3/2.∞.3/2.∞.3/2.12/5.6.12/5 3.−12/5.−6.−12/5.3.∞.3.∞ |

non-Wythoffian | p6m | ||

There are two uniform tilings for the vertex configuration 4.8.−4.8.−4.∞ (Grünbaum et al., 2.10 and 2.11) and also two uniform tilings for the vertex configuration 4.8/3.4.8/3.−4.∞ (Grünbaum et al., 2.12 and 2.13), with different symmetries. There is also a third tiling for each vertex configuration that is only pseudo-uniform (vertices come in two symmetry orbits). They use different sets of square faces. Hence, for star Euclidean tilings, the vertex configuration does not necessarily determine the tiling.[2]

In the pictures below, the included squares with horizontal and vertical edges are marked with a central dot. A single square has edges highlighted.[2]

-

2.10 and 2.12 (p4m)

-

2.11 and 2.13 (p4g)

-

Pseudo-uniform

The tilings with zigzags are listed below. {∞𝛼} denotes a zigzag with angle 0 < 𝛼 < π. The apeirogon can be considered the special case 𝛼 = π. The symmetries are given for the generic case, but there are sometimes special values of 𝛼 that increase the symmetry. Tilings 3.1 and 3.12 can even become regular; 3.32 already is (it has no free parameters). Sometimes, there are special values of 𝛼 that cause the tiling to degenerate.[2]

| Tilings with zigzags | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Grünbaum et al., 1981[2] | Diagram | Vertex Config. |

Symmetry |

| 3.1 |  |

∞𝛼.∞β.∞γ 𝛼+β+γ=2π |

p2 |

| 3.2 |  |

∞𝛼.∞β.−∞𝛼+β 0<𝛼+β≤π |

p2 |

| 3.3 |  |

3.3.∞π−𝛼.−3.∞𝛼+2π/3 0≤𝛼≤π/6 |

pgg |

| 3.4 |  |

3.3.−∞π−𝛼.−3.∞−𝛼+2π/3 0≤𝛼<π/3 |

pgg |

| 3.5 |  |

4.4.∞φ.4.4.−∞φ φ=2 arctan(n/k), nk even, (n,k)=1 drawn for φ=2 arctan 2 |

pmg |

| 3.6 |  |

4.4.∞φ.−4.−4.∞φ φ=2 arctan(n/k), nk even, (n,k)=1 drawn for φ=2 arctan 1/2 |

pmg |

| 3.7 |  |

3.4.4.3.−∞2π/3.−3.−∞2π/3 | cmm |

| 3.8 |  |

3.−4.−4.3.−∞2π/3.−3.−∞2π/3 | cmm |

| 3.9 |  |

4.4.∞π/3.∞.−∞π/3 | p2 |

| 3.10 |  |

4.4.∞2π/3.∞.−∞2π/3 | p2 |

| 3.11 |  |

∞.∞𝛼.∞.∞−𝛼 0<𝛼<π |

cmm |

| 3.12 |  |

∞𝛼.∞π−𝛼.∞𝛼.∞π−𝛼 0<𝛼≤π/2 |

cmm |

| 3.13 |  |

3.∞𝛼.−3.−∞𝛼 π/3<𝛼<π |

p31m |

| 3.14 |  |

4.4.∞2π/3.4.4.−∞2π/3 | p31m |

| 3.15 |  |

4.4.∞π/3.−4.−4.−∞π/3 | p31m |

| 3.16 |  |

4.∞𝛼.−4.−∞𝛼 0<𝛼<π, 𝛼≠π/2 |

p4g |

| 3.17 |  |

4.−8.∞π/2.∞.−∞π/2.−8 | cmm |

| 3.18 |  |

4.−8.∞π/2.∞.−∞π/2.−8 | p4 |

| 3.19 |  |

4.8/3.∞π/2.∞.−∞π/2.8/3 | cmm |

| 3.20 |  |

4.8/3.∞π/2.∞.−∞π/2.8/3 | p4 |

| 3.21 |  |

6.−12.∞π/3.∞.−∞π/3.−12 | p6 |

| 3.22 |  |

6.−12.∞2π/3.∞.−∞2π/3.−12 | p6 |

| 3.23 |  |

6.12/5.∞π/3.∞.−∞π/3.12/5 | p6 |

| 3.24 |  |

6.12/5.∞2π/3.∞.−∞2π/3.12/5 | p6 |

| 3.25 |  |

3.3.3.∞2π/3.−3.∞2π/3 | p31m |

| 3.26 |  |

3.∞.3.−∞2π/3.−3.−∞2π/3 | cm |

| 3.27 |  |

3.∞.−∞2π/3.∞.−∞2π/3.∞ | p31m |

| 3.28 |  |

3.∞2π/3.∞2π/3.−3.−∞2π/3.−∞2π/3 | p31m |

| 3.29 |  |

∞.∞π/3.∞π/3.∞.−∞π/3.−∞π/3 | cmm |

| 3.30 |  |

∞.∞π/3.−∞2π/3.∞.∞2π/3.−∞π/3 | p2 |

| 3.31 |  |

∞.∞2π/3.∞2π/3.∞.−∞2π/3.−∞2π/3 | cmm |

| 3.32 |  |

∞π/3.∞π/3.∞π/3.∞π/3.∞π/3.∞π/3 | p6m |

| 3.33 |  |

∞π/3.−∞2π/3.−∞2π/3.∞π/3.−∞2π/3.−∞2π/3 | cmm |

The tiling pairs 3.17 and 3.18, as well as 3.19 and 3.20, have identical vertex configurations but different symmetries.[2]

Tilings 3.7 through 3.10 have the same edge arrangement as 2.1 and 2.2; 3.17 through 3.20 have the same edge arrangement as 2.10 through 2.13; 3.21 through 3.24 have the same edge arrangement as 2.18 through 2.23; and 3.25 through 3.33 have the same edge arrangement as 1.25 (the regular triangular tiling).[2]

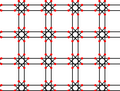

Self-dual tilings

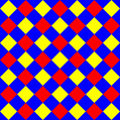

A tiling can also be self-dual. The square tiling, with Schläfli symbol {4,4}, is self-dual; shown here are two square tilings (red and black), dual to each other.

Uniform tilings using regular or isotoxal polygrams as nonconvex isotoxal simple polygons

π/4.4**

π/2.8*

π/4, is considered not edge-to-edge due to the large square, although the latter can be interpreted as a star polygon with four pairs of collinear edges.

Seeing a

Also, the outlines of certain non-regular isotoxal star polygons are nonconvex isotoxal (simple) polygons with as many (shorter) sides and alternating the same outer and "inner" internal angles; seeing this kind of isotoxal star polygons as their outlines allows it to be used in a tiling, and seeing isotoxal simple polygons as "regular" allows this kind of isotoxal star polygons to (but not all of them can) be used in a "uniform" tiling.

An isotoxal simple 2n-gon with outer internal angle 𝛼 is denoted by {n𝛼}; its outer vertices are labeled as n*

𝛼, and inner ones as n**

𝛼.

These expansions to the definition for a tiling require corners with only 2 polygons to not be considered vertices — since the vertex configuration for vertices with at least 3 polygons suffices to define such a "uniform" tiling, and so that the latter has one vertex configuration alright (otherwise it would have two) —. There are 4 such uniform tilings with adjustable angles 𝛼, and 18 such uniform tilings that only work with specific angles, yielding a total of 22 uniform tilings that use star polygons.[4]

All of these tilings, with possible order-2 vertices ignored, with possible double edges and triple edges reduced to single edges, are topologically related to the ordinary uniform tilings (using only convex regular polygons).

3.6* 𝛼.6** 𝛼 Topol. related to 3.12.12 |

4.4* 𝛼.4** 𝛼 Topol. related to 4.8.8 |

6.3* 𝛼.3** 𝛼 Topol. related to 6.6.6 |

3.3* 𝛼.3.3** 𝛼 Topol. related to 3.6.3.6 |

4.6.4* π/6.6 Topol. related to 4.4.4.4 |

(8.4* π/4)2 Topol. related to 4.4.4.4 |

12.12.4* π/3 Topol. related to 4.8.8 |

3.3.8* π/12.4** π/3.8* π/12 Topol. related to 4.8.8 |

3.3.8* π/12.3.4.3.8* π/12 Topol. related to 4.8.8 |

3.4.8.3.8* π/12 Topol. related to 4.8.8 |

5.5.4* π/10.5.4* π/10 Topol. related to 3.3.4.3.4 |

6.6.6

|

(4.6* π/6)3 Topol. related to 6.6.6 |

6.6.6

|

(6.6* π/3)2 Topol. related to 3.6.3.6 |

(12.3* π/6)2 Topol. related to 3.6.3.6 |

3.4.6.3.12* π/6 Topol. related to 4.6.12 |

3.3.3.12* π/6.3.3.12* π/6 Topol. related to 3.12.12 |

18.18.3* 2π/9 Topol. related to 3.12.12 |

3.6.6* π/3.6 Topol. related to 3.4.6.4 |

8.3* π/12.8.6* 5π/12 Topol. related to 3.4.6.4 |

9.3.9.3* π/9 Topol. related to 3.6.3.6 |

Uniform tilings using convex isotoxal simple polygons

Non-regular isotoxal either star or simple 2n-gons always alternate two angles. Isotoxal simple 2n-gons, {n𝛼}, can be convex; the simplest ones are the rhombi (2×2-gons), {2𝛼}. Considering these convex {n𝛼} as "regular" polygons allows more tilings to be considered "uniform".

3.2* π/3.6.2** π/3 Topol. related to 3.4.6.4 |

4.4.4.4 Topol. related to 4.4.4.4 |

(2* π/4.2** π/4)2 Topol. related to 4.4.4.4 |

2* π/4.2* π/4.2** π/4.2** π/4 Topol. related to 4.4.4.4 |

4.2* π/4.4.2** π/4 Topol. related to 4.4.4.4 |

See also

- Wythoff symbol

- List of uniform tilings

- Uniform tilings in hyperbolic plane

- Uniform polytope

References

- ^ Tiles and Patterns, Table 12.3.1, p. 640

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4612-5650-2.

- ^ a b Jim McNeill

- ^ Tilings and Patterns, Branko Gruenbaum, G. C. Shephard, 1987, 2.5 Tilings using star polygons, pp. 82–85.

- Norman Johnson Uniform Polytopes, Manuscript (1991)

- N. W. Johnson: The Theory of Uniform Polytopes and Honeycombs, Ph. D. Dissertation, University of Toronto, 1966

- ISBN 0-7167-1193-1. (Star tilings section 12.3)

- JSTOR 91532(Table 8)

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Uniform tessellation". MathWorld.

- Uniform Tessellations on the Euclid plane

- Tessellations of the Plane

- David Bailey's World of Tessellations

- k-uniform tilings

- n-uniform tilings

- Klitzing, Richard. "4D Euclidean tilings".

| Space | Family | / / | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E2 | Uniform tiling | 0[3] | δ3 | hδ3 | qδ3 | Hexagonal |

| E3 | Uniform convex honeycomb

|

0[4] | δ4 | hδ4 | qδ4 | |

| E4 | Uniform 4-honeycomb

|

0[5] | δ5 | hδ5 | qδ5 | 24-cell honeycomb |

| E5 | Uniform 5-honeycomb

|

0[6] | δ6 | hδ6 | qδ6 | |

| E6 | Uniform 6-honeycomb

|

0[7] | δ7 | hδ7 | qδ7 | 222 |

| E7 | Uniform 7-honeycomb

|

0[8] | δ8 | hδ8 | qδ8 | 133 • 331 |

| E8 | Uniform 8-honeycomb

|

0[9] | δ9 | hδ9 | qδ9 | 152 • 251 • 521 |

| E9 | Uniform 9-honeycomb

|

0[10] | δ10 | hδ10 | qδ10 | |

| E10 | Uniform 10-honeycomb | 0[11] | δ11 | hδ11 | qδ11 | |

| En−1 | Uniform (n−1)-honeycomb | 0[n]

|

δn | hδn | qδn | 1k2 • 2k1 • k21 |