United Nations Secretariat Building

| United Nations Secretariat Building | |

|---|---|

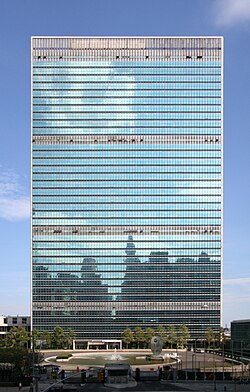

The United Nations Secretariat Building in New York City | |

| |

| General information | |

| Status | Completed |

| Type | Office |

| Location | International territory in Manhattan, New York City |

| Coordinates | 40°44′56″N 73°58′05″W / 40.74889°N 73.96806°W |

| Construction started | September 14, 1948 |

| Completed | June 1951 |

| Opening | August 21, 1950 |

| Owner | United Nations |

| Height | |

| Roof | 505 ft (154 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 39 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | United Nations Headquarters Board of Design (Wallace Harrison, Oscar Niemeyer, Le Corbusier, etc.) |

| Main contractor |

|

| References | |

| [1][2] | |

The United Nations Secretariat Building is a

The Secretariat Building is designed as a rectangular slab measuring 72 by 287 ft (22 by 87 m); it is oriented from north to south and is connected with other UN headquarters buildings. The wider western and eastern

The design process for the United Nations headquarters formally began in February 1947, and a groundbreaking ceremony for the Secretariat Building occurred on September 14, 1948. Staff started moving into the building on August 21, 1950, and it was completed in June 1951. Within a decade, the Secretariat Building was overcrowded, prompting the UN to build additional office space nearby. The building started to deteriorate in the 1980s due to a lack of funding, worsened by the fact that it did not meet modern New York City building codes. UN officials considered renovating the building by the late 1990s, but the project was deferred for several years. The Secretariat Building was renovated starting in 2010 and reopened in phases from July to December 2012.

Site

The Secretariat Building is part of the

The Secretariat Building is directly connected to the Conference Building (housing the Security Council) at its northeast and the Dag Hammarskjöld Library to the south. It is indirectly connected to the United Nations General Assembly Building to the north, via the Conference Building.[4][9] West of the Secretariat Building is a circular pool with a decorative fountain in its center,[10][11] as well as a sculpture executed in 1964 by British artist Barbara Hepworth in memory of Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld.[12] The Japanese Peace Bell is just north of the building,[13] and a grove of sycamore trees is planted next to the Secretariat Building.[14] On the western part of the site, along First Avenue, are the flags of the UN, its member states, and its observer states.[15]

Outside of the UN headquarters, Robert Moses Playground is directly to the south, and Tudor City and the Ford Foundation Center for Social Justice are to the west. In addition, the Millennium Hilton New York One UN Plaza hotel (within One and Two United Nations Plaza) is to the northwest.[3] The building is physically isolated from other nearby structures, with the nearest New York City Subway station being several blocks away.[6] Because of this, the Secretariat Building appears as a freestanding tower.[16]

Historically, the site was part of a cove called Turtle Bay. The cove, located between what is now 45th and 48th Streets, was fed by a stream that ran from the present-day intersection of Second Avenue and 48th Street.[17] A creek from the southern end of modern-day Central Park also drained into Turtle Bay.[18] The first settlement on the site was a tobacco farm built in 1639.[19] The site was developed with residences in the 19th century.[13] Slaughterhouses operated on the eastern side of First Avenue for over a hundred years until the construction of the United Nations headquarters.[19] The UN purchased the site in 1946 under the sole condition that it could never slaughter cattle on the land.[20]

Architecture

The Secretariat Building was designed in the

Form and facade

The building is designed as a rectangular slab measuring 72 by 287 ft (22 by 87 m),[a] with the longer axis oriented north–south.[31][32] The Secretariat's architects wanted to design the massing as a slab without any setbacks.[33][34] This contrasted with older buildings, such as those at the Rockefeller Center complex, which featured setbacks corresponding to the tops of their elevator banks.[33]

The cornerstone of the UN headquarters was dedicated at the Secretariat Building in 1949.[35][36] The cornerstone is a block of New Hampshire granite, weighing 3.75 short tons (3.35 long tons; 3.40 t) and measuring 4 by 3 by 3 ft (1.22 by 0.91 by 0.91 m). The name of the United Nations is inscribed in English, Spanish, French, Russian, and Chinese, which at the time were the five official languages of the United Nations.[37] The cornerstone was initially intended to be relocated to the General Assembly Building when that building was completed.[35] UN officials ultimately decided to permanently affix the stone to a high pedestal next to the Secretariat Building.[38]

Curtain walls

The wider western and eastern

When the building was completed, the curtain walls were cantilevered 2 ft 9 in (0.84 m) from the superstructure[27][54][50] and were attached to the concrete floor slabs.[55] Each of the original windows were aluminum sash windows,[40][49][56] separated by aluminum mullions that projected slightly from the facade.[33][48] The sash windows were compatible with conventional window cleaning equipment.[49] The modern curtain walls are hung from the superstructure via outrigger plates, and there are projecting aluminum mullions similar to those on the original sash windows.[55] The western and eastern elevations are each divided vertically into ten bays, each measuring 28 ft (8.5 m) wide. Within each bay are seven panels, each measuring 4 ft (1.2 m) wide and 12 ft (3.7 m) tall.[27][54] Three of the old curtain-wall panels are preserved in the Museum of Modern Art.[57]

Marble slabs

The narrower northern and southern elevations are made of masonry[40] clad with Vermont marble.[45][62] These elevations rise as unbroken slabs and do not contain any openings.[29][54] The building's steel superstructure, including steel bracing, was concealed within these marble slabs.[30] According to Harrison, the marble walls not only allowed the Secretariat Building to be seen as a monument, but also reduced competition between staff members who wanted corner offices.[63]

Structural features

The foundation includes concrete piers that extend down to the underlying bedrock.[18][64] Steel pilings are used at points where the bedrock is more than 20 ft (6.1 m) deep. The piles are installed in sets of 5 to 20 and range from 50 to 90 ft (15 to 27 m) deep. Each set of pilings is covered by a concrete cap.[18] The building's structural loads are carried by an internal superstructure[42] that includes about 13,000 short tons (12,000 long tons; 12,000 t) of steel.[31][32] The columns of the superstructure are arranged in a 10×3 grid. The ten north–south bays are all 28 ft (8.5 m) wide, but the three west–east bays are all of different widths.[27] The westernmost bay is 20 ft 8 in (6.30 m) wide; the central bay is 18 ft 2 in (5.54 m) wide; and the easternmost bay is 27 by 8 ft (8.2 by 2.4 m) wide. The narrow central bay was used as an elevator core.[27][30] The floors are generally made of mesh and reinforced concrete, which is covered by either terrazzo, cement, asphalt-tile, or carpeting. Electrical and air ducts are placed underneath each floor slab. The interior partition walls are made of rough masonry, marble, plaster, glass, aluminum, or pointed steel.[40]

Interior

The Secretariat Building was constructed with 889,000 sq ft (82,600 m2) of space and, at the time of its completion, could accommodate 4,000 workers.

The Secretariat Building was built with 21 high-speed passenger elevators and eight bronze-and-glass escalators.[29][56] The building has two freight elevators serving all stories and three banks of six passenger elevators. The low-rise, mid-rise, and high-rise banks of elevators respectively serve floors 2–15, 16–27, and 28–39.[27] The elevators were programmed so that, if a person on one of the office floors was waiting for a "down" elevator for more than 60 seconds, they would instead be able to enter the next "up" elevator.[65] The elevators were initially staffed by elevator operators before being converted to manual operation in 1967.[70]

Lower stories

Under the building is a three-story garage for UN employees, with 1,500 parking spaces.

The building's lobby has black-and-white terrazzo floors,[74][75] as well as columns covered with green Italian marble.[74] Black-and-white terrazzo floors are also present at all entryways, and all corridors in the building near the elevator banks.[75] There are full-height windows within the lobby.[76] Also within the lobby is Peace, a 15 by 12 ft (4.6 by 3.7 m) stained glass window by Marc Chagall, dedicated in memory of Hammarskjöld in 1964.[77][78] When the building was constructed, the lowest stories were to contain broadcasting studios, press offices, staff rooms, and other functions.[44] Media correspondents for the United Nations occupied floors 2 to 4.[79] There was a meditation space on floor 2[80] that doubled as a press conference room.[81] In addition, there was a bank branch on floor 4.[66] The fourth and fifth floors were connected by an open stairway.[82]

On floor 5 are employee amenities, including a health clinic and a passageway to a staff dining room above the adjacent Conference Building.

Offices

The offices were placed on the upper floors.[44] Each office story has a gross floor area of 19,000 sq ft (1,800 m2).[30] There were private offices on the perimeter of each floor. Secretarial offices, support staff, and elevator cores were clustered in the middle of each story.[30][88] The eastern side of the building was more desirable because it faced the East River, and higher-level diplomats needed large amounts of space for secretaries, filing cabinets, and other functions.[30][86] As a result, low-level officials worked on the shallower western side of the building, while high-level officials worked on the eastern side.[30] Spaces such as the women's restrooms were originally also placed on the western side, overlooking Midtown Manhattan.[86] High-ranking officials, such as Under-Secretaries-General, had wood-paneled suites with attached conference rooms.[89]

The offices are divided into modules measuring 4 ft (1.2 m) wide, with movable partitions that align with the facade's mullions. The offices initially included French desks as well as aluminum chairs.

The Secretariat Building's air-conditioning system had 4,000 individual sets of controls.[92][78] This system not only reduced cooling costs by at least 25 percent, but also allowed delegates and staff to customize the temperatures of their own offices.[92] Offices within 12 ft (3.7 m) of a window are cooled by high-velocity air conditioning units underneath the windows.[27][78] For offices near the center of the building, cool air is delivered through low-velocity units in the ceilings. The cool air was provided by a pair of centrifugal compressors, which could collectively generate 2,300 tons of air. There are hot-water heating units beneath the windows, within the north and south walls of the building, and underneath the floor slab of the first story; in addition, there are steam heaters in the pipe galleries.[27] The dehumidifiers on each story are supplied by chilled water from the East River[27][65] at a rate of more than 14,000 U.S. gal (53,000 L) per minute.[65][93] The use of East River water precluded the need for a dedicated cooling tower, which would have required increasing the building's height and strengthening the superstructure.[93]

On floor 38 are offices and an apartment for the

History

Development

Real estate developer William Zeckendorf purchased a site on First Avenue in 1946, intending to create a development called "X City", but he could not secure funding for the development.[96][97][98] At the time, the UN was operating out of a temporary headquarters in Lake Success, New York,[99] although it wished to build a permanent headquarters in the US.[100] Several cities competed to host the UN headquarters before New York City was selected.[100][101] John D. Rockefeller Jr. paid US$8.5 million for an option on the X City site,[100][102] and he donated it to the UN in December 1946.[102][103][104] The UN accepted this donation, despite the objections of several prominent architects such as Le Corbusier.[102][103] The UN hired planning director Wallace Harrison, of the firm Harrison & Abramovitz, to lead the headquarters' design.[102] He was assisted by a Board of Design composed of ten architects.[105][23][24]

Planning

The design process for the United Nations headquarters formally began in February 1947.[106][107][108] Each architect on the Board of Design devised his own plan for the site, and some architects created several schemes.[24][109] All the plans had to include at least three buildings: one each for the General Assembly, the Secretariat, and conference rooms.[24][110] The plans had to comply with several "basic principles"; for example, the Secretariat Building was to be a 40-story tower without setbacks.[34] It would be a freestanding tower surrounded by shorter structures, something which may have been influenced by Le Corbusier's ideals.[110] Early designs called for the Secretariat tower to accommodate 2,300 workers; the architects subsequently considered a 5,265-worker capacity before finalizing the capacity at 4,000 workers.[22] The tower was to be placed at the south end of the complex because it was near 42nd Street, a major crosstown street,[22] and because the underlying bedrock was shallowest at this end.[110]

By March 1947, the architects had devised preliminary sketches for the headquarters.[34][111] The same month, the Board of Design published two alternative designs for a five-building complex, anchored by the Secretariat Building to the south and a pair of 35-story buildings to the north.[111][112][113] After much discussion, Harrison decided to select a design based on the proposals of two board members, Oscar Niemeyer and Le Corbusier.[48][23][114] Even though the design process was a collaborative effort,[109][114] Le Corbusier took all the credit, saying the buildings were "100% the architecture and urbanism of Le Corbusier".[111] The Board of Design presented their final plans for the United Nations headquarters in May 1947. The plans called for a 45-story Secretariat tower at the south end of the site, a 30-story office building at the north end, and several low-rise structures (including the General Assembly Building) in between.[115][116] The committee unanimously agreed on this plan.[110]

The Secretariat tower was planned to be the first building on the site,[107][108] and it was initially projected to be finished in late 1948.[117] The project was facing delays by mid-1947, when a slaughterhouse operator on the site requested that it be allowed to stay for several months.[20][117] The complex was originally planned to cost US$85 million.[28][118] Demolition of the site started in July 1947.[119][120] The same month, UN Secretary-General Trygve Lie and the architects began discussing ways to reduce construction costs by downsizing the headquarters.[118] Lie then submitted a report to the General Assembly in which he recommended reducing the Secretariat tower from 45 to 39 stories.[78][121] The UN had contemplated installing a swimming pool in the building during the planning process, but the pool was eliminated due to objections from American media organizations.[122] The General Assembly voted to approve the design for the headquarters in November 1947.[78][120] By the next month, the architects were considering adding granite panels to the western elevation of the facade, since sunlight would enter through that facade during the majority of the workday.[123]

In April 1948, US President Harry S. Truman requested that the United States Congress approve an interest-free loan of US$65 million to fund construction.[124][125] Because Congress did not approve the loan for several months, there was uncertainty over whether the project would proceed.[120][126] Around that time, the UN had decided to reduce the Secretariat Building to 39 stories. The height reduction, along with other modifications, was expected to save US$3 million.[125][127] Congress authorized the loan in August 1948, of which US$25 million was made available immediately from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation.[128][129] Lie predicted the US$25 million advance would only be sufficient to pay for the Secretariat Building's construction.[127] To ensure that the project would remain within its US$65 million budget, Lie delayed the installation of the building's furnishings, thereby saving US$400,000.[130]

Construction

The groundbreaking ceremony for the initial buildings occurred on September 14, 1948.[120][131] Workers removed a bucket of soil to mark the start of work on the Secretariat Building's basement.[131] The next month, Harrison requested that its 58 members and the 48 U.S. states participate in designing the interiors of the building's conference rooms. It was believed that if enough countries designed their own rooms, the UN would be able to reduce its expenditures.[132] Also in October, the American Bridge Company was hired to construct the steel superstructure of the Secretariat Building.[31][32] Le Corbusier insisted that the facade of the Secretariat Building contain brises soleil, or sun-breakers, even as Harrison argued that the feature would be not only expensive but also difficult to clean during the winter.[48][133] This prompted the architects to erect a mockup of the planned facade on the roof of the nearby Manhattan Building.[134][135][136] By late 1948, the Secretariat Building was scheduled to receive its first tenants in 1950.[137][138]

Fuller Turner Walsh Slattery Inc., a joint venture between the George A. Fuller Company, Turner Construction, the Walsh Construction Company, and the Slattery Contracting Company, was selected in December 1948 to construct the Secretariat Building, as well as the foundations for the remaining buildings.[139][140] The next month, the UN formally awarded a US$23.8 million contract for the Secretariat Building's construction to the joint venture.[141][142] The Secretariat Building was to be completed no later than January 1, 1951, or the joint venture would pay a minimum penalty of US$2,500 per day to the UN.[143] The joint venture had started constructing the piers under the building by the end of January 1949,[144] and site excavations were completed the next month.[145][146] In April 1949, workers erected the first steel beam for the Secretariat Building, and the flag of the United Nations was raised above the first beam.[147] The cornerstone of the headquarters was originally supposed to be laid at the Secretariat Building on April 10, 1949. Lie delayed the ceremony after learning that Truman would not present to officiate the cornerstone laying.[148][37] The cornerstone was held in a storage yard in Maspeth, Queens, in the meantime.[37]

The Secretariat Building's steel structure had been completed by October 1949.[62][149] At a topping out ceremony on October 5, the UN flag was hoisted atop the roof of the newly completed steel frame.[56][150] The facade was still not completed; the aluminum had only reached the 18th floor and the glass had reached the 9th floor.[62] Six days later, Truman accepted an invitation to the cornerstone-laying ceremony.[151][152] New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey laid the headquarters' cornerstone on October 24, 1949, the fourth anniversary of the United Nations' founding.[35][36][153] Construction workers completed a sample office on the eighth floor in January 1950.[38] By that June, the building was 80 percent completed, and the first occupants were scheduled to move there within two or three months. The southern half of the parking lot, underneath the Secretariat Building, was also finished; the northern half was being completed as part of the General Assembly Building.[71][72] The building as a whole was not planned to be completed until January 1951.[71][154]

Completion and early years

Opening

The first portion of the building to be completed was its parking lot, which opened in July 1950.[72][74] Staff started moving into the Secretariat on August 21, 1950,[155][156] with 450 staff members moving into the basement levels and the first 15 stories.[157][158] Staff members with frequent meetings, such as interpreters, remained at the Lake Success office for the time being.[122] The lobby contained a temporary location for the UN's bookstore, which relocated to the General Assembly Building in 1952 following that structure's completion.[159] At the time, the UN had 57 member states and could accommodate 13 more nations.[160]

Initially, the UN did not allow visitors in the Secretariat Building.[155][156] Shortly after the building opened, it was discovered that smoke from Consolidated Edison's nearby Waterside Generating Station was polluting the air intakes for the building's air conditioning system.[161] The UN ultimately agreed in November 1950 to relocate the Secretariat Building's air intakes.[162] The same month, the UN decided to spend US$360,000 to furnish three floors of offices for UNICEF and the Technical Assistance Administration.[163] Media correspondents moved into the building in January 1951,[79][164] and the Secretariat Building was fully occupied by that June.[165][166] Building officials also announced in early 1951 that they would repair the windows, which were leaking due to poor weather-stripping.[167] Officials had recorded 4,916 instances of leaks before the windows were repaired in mid-1951. During a storm that October, after the windows had been repaired, officials recorded only 16 leaks.[59]

The building had 3,000 workers by the end of 1951. A Chicago Daily Tribune reporter said the staff were "neither united nor very peaceful", in part because staff tended to sit with those from their own countries.[168] William R. Frye of The Christian Science Monitor said that the Secretariat Building's vertical office layout had led many staff members to express nostalgia for the old Lake Success offices.[122] The Secretariat Building's cafeteria opened in January 1952,[169] and the fountain outside the building was dedicated in June 1952.[10][11] The Secretariat Building finally began receiving visitors that year, after the rest of the UN complex opened.[170] By the end of 1952, the complex received about 1,500 visitors per day.[171] Workers cleaned the building for the first time in April 1953,[172] and repairs to the facade were completed by that September.[58]

UN expansion

The UN's membership expanded during the 1950s, prompting officials to expand the building's communications equipment in 1958.[173] The next year, Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld proposed allocating US$635,000 to install automatic elevators in the Secretariat Building due to increasing labor costs.[174] At that time, the building received about 2,500 to 3,000 tourists a day.[13] By 1962, the Secretariat Building was occupied by 3,000 Secretariat employees (three-quarters of the total staff), as well as other UN organizations.[175] That year, Secretary-General U Thant proposed constructing a two-story annex at a cost of US$6.3 million, but a UN committee rejected this proposal.[176] A journalists' club in the building was opened the same year.[177] In 1964, a UN panel approved a proposal to replace the elevators and renovate two of the building's unoccupied stories, but it rejected other proposals to expand the headquarters.[178] Two years later, Thant proposed constructing another office building within the UN headquarters. By then, the Secretariat Building was nearing capacity, and some organizations, such as UNICEF, had been forced to relocate.[179][180] The building's manual elevators were replaced by automatic cabs in 1967.[70]

Yet another expansion of the UN headquarters, including a park connected with the Secretariat Building, was proposed in 1968.[181] This led to the construction of One United Nations Plaza, on 44th Street just outside the UN complex, in 1975.[182][183] The main headquarters was expanded slightly from 1978 to 1981. As part of this project, a new cafeteria was built at the northern end of the headquarters, and the Secretariat Building's cafeteria was converted into additional offices.[85][160] Another office tower outside the headquarters proper, Two United Nations Plaza, was completed in 1983.[184] By then, the Secretariat had over 6,000 employees, some of whom were forced to work within the United Nations Plaza towers.[184] The new buildings were barely sufficient to accommodate the UN's demand for office space; the organization itself had expanded to 140 members by the 1970s.[160] Furthermore, the Secretariat Building's tenant list had largely remained constant from its opening through the end of the 20th century. As a result, the building housed several departments that had existed since the 1950s but were unrelated to the Secretariat. Newer Secretariat departments occupied space in nearby office buildings rather than in the United Nations Secretariat Building.[91]

Maintenance issues and renovation proposals

Due to funding shortfalls in the 1980s, the UN diverted funding from its headquarters' maintenance fund to peacekeeping missions and other activities. The Secretariat Building's heating and cooling costs alone amounted to US$10 million a year.[185] Because the headquarters was an extraterritorial territory, the Secretariat Building was exempt from various building regulations.[186][187] Furthermore, the building's machinery created electromagnetic fields, which reportedly made some employees ill. Although the General Assembly had voted to fund the installation of electromagnetic shields in the building in 1990, that money was instead used for roof repairs.[185]

By 1998, the building had become technologically dated, and UN officials considered renovating the headquarters.[91] The Secretariat Building did not meet modern New York City building regulations: it lacked a sprinkler system, the space leaked extensively, and there were large amounts of asbestos that needed to be removed.[188][185] The mechanical systems were so outdated that the UN had to manufacture its own replacement parts,[52][189] and up to one quarter of the building's heat escaped through leaks in the curtain wall.[52] The building used massive amounts of energy because, at the time of the tower's construction, the UN had not been as concerned about energy conservation.[42] Part of one story had been vacated because of interference from electromagnetic fields.[185] The New York Times wrote that "if the United Nations had to abide by city building regulations [...] it might well be shuttered".[185][190] At the time, the UN had proposed renovating the building for US$800 million, as UN officials had concluded that the long-term cost of renovations would be cheaper than doing nothing.[185]

The UN commissioned a report from engineering firm

The UN then decided to renovate its existing structures over seven years for US$1.6 billion. The Secretariat Building would be renovated in four phases, each covering ten stories, and the UN would lease an equivalent amount of office space nearby.[195] Louis Frederick Reuter IV was the original architect for the renovation, but he resigned in 2006 following various disputes between UN and US officials. Michael Adlerstein was hired as the new project architect.[52] Engineering firm Skanska was hired to renovate the Secretariat, Conference, and General Assembly buildings in July 2007.[196][197] At that point, the cost of the project had risen to US$1.9 billion.[52][197] Prior to the start of the renovation, in 2008, Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon approved a pilot program to reduce heat emissions by raising temperatures throughout the building. By then, the offices had been rearranged so frequently that the heating and cooling system no longer worked as intended.[198]

Substantial renovation and reopening

The renovation of the United Nations headquarters formally began in 2008.[199] Adlerstein planned to reconstruct the Secretariat Building's offices entirely while preserving the appearance of the exterior and public spaces. All of the building's 5,000 workers had to relocate to nearby office space.[200] Work on the building began in mid-2010.[91] The work involved redesigning the mechanical systems, adding blast protection, and upgrading the building to conform to New York City building codes.[201] In addition, large amounts of asbestos were removed from the structure, and workers installed a fire-alarm and sprinkler system.[201][47] The curtain wall was also rebuilt in several sections, starting from the lowest levels and working upward.[55] The building was also retrofitted with various green building features as part of the project.[200][202]

The building reopened in phases, with the first workers returning in July 2012.[91][203] On October 29, 2012, the basement of the UN complex was flooded due to Hurricane Sandy, leading to a three-day closure and the relocation of several offices.[204] By that December, the last workers had moved back into the Secretariat Building. Following the renovation, the Secretariat Building housed all of the Secretariat's divisions. Some of the building's previous occupants, such as the Department of Peace Operations, had relocated to other buildings.[91] In 2019, due to a budget shortfall, the UN curtailed heating and air-conditioning service in the building, and it shut down some of the Secretariat Building's escalators.[205]

Impact

When the Secretariat Building was being constructed in June 1949, Building magazine described the tower as "a vast marble frame for two enormous windows ... a mosaic reflecting the sky from a thousand facets".[30] Newsweek characterized the structure as being "a cross between Hiroshima, an Erector set, and a glazier's dream house".[206] Upon the building's completion in 1951, Office Management and Equipment magazine presented UN officials with a plaque recognizing the building as "office of the year".[207][208] The Secretariat Building's staff quickly nicknamed it the "Glass House".[4][168]

Following the building's completion, it received a significant amount of architectural commentary, though reviews were mixed.[209][210] Vogue magazine compared the tower to an "ice-cream sandwich", describing it as being "as much monument as office".[21] Time magazine wrote: "Some architectural critics have called the Secretariat everything from a 'magnified radio console' to 'a sandwich on end'."[211] The architect Henry Stern Churchill wrote of the building: "Visually it completely dominates the group; when one thinks of U.N. one thinks only of the vast green-glass, marble-end slab."[28][61] Architectural Forum wrote: "Not since Lord Carnarvon discovered King Tut's Tomb in 1922 had a building caused such a stir."[61][212] The architect Aaron Betsky wrote in 2005: "The Secretariat becomes both an abstraction of the office grids behind it and an abstract painting itself, posed in front of Manhattan as one approaches from the major airports on Long Island."[48]

Some critics had negative views of the building. British architect Giles Gilbert Scott described the Secretariat Building as "that soapbox", saying: "I don't know whether that's architecture."[213] Architectural critic Lewis Mumford regarded the building as a "superficial aesthetic triumph and an architectural failure" that was only enlivened during the nighttime when the offices were illuminated.[209][214] He wrote of the interiors: "So far from the being the model office building it might have been, it really is a very conventional job."[61][215] Mumford reluctantly acknowledged that the building could be a global symbol, saying that the building represented the fact that "the managerial revolution has taken place and that bureaucracy rules the world".[210]

Other glass-walled buildings in Manhattan,[43][216] such as Lever House,[217] the Corning Glass Building,[218] and the Springs Mills Building, were built after the United Nations Secretariat Building.[216] The development of Lever House and the glass-walled Seagram Building, in turn, led to development of other glass-walled skyscrapers worldwide.[43] Additionally, One United Nations Plaza was designed to complement the style of the Secretariat Building.[182] The Secretariat Building and its connected structures have been depicted in numerous films such as The Glass Wall (1953) and North by Northwest (1959).[219] The 2005 film The Interpreter was the first filmed inside the headquarters.[220][221]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Adlerstein 2015, p. 6, gives alternate measurements of 287 by 74 ft (87 by 23 m).

- ^ Most of the ceiling is 8 ft (2.4 m) tall, but the sections of ceiling near each window are 9.5 ft (2.9 m) tall.[91]

Citations

- ^ a b "United Nations Secretariat Building – The Skyscraper Center". Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. October 28, 2015. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ a b c "United Nations Secretariat Building". Emporis. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ ProQuest 1538823528.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-58477-077-0. Archivedfrom the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ a b "Agreement regarding the Headquarters of the United Nations" (PDF). United Nations Treaty Collection. November 21, 1947. p. 12 (PDF p. 2). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 22, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ from the original on August 2, 2022. Retrieved August 2, 2022.

- ^ UN Chronicle 1977, p. 37.

- ^ from the original on July 27, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ ProQuest 1322306706.

- from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ ProQuest 493600161.

- from the original on December 29, 2018. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ Endrst, Elsa B. (December 1992). "So proudly they wave ... flags of the United Nations". UN Chronicle. Vol. 29, no. 4. Archived from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved October 24, 2011 – via CBS Business Library.

- from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ "Turtle Bay Gardens Historic District" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. July 21, 1983. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 152180408.

- ^ a b Iglauer 1947, p. 570.

- ^ a b Iglauer 1947, p. 572.

- ^ a b Vogue 1952, p. 125.

- ^ a b c d Churchill 1952, p. 109.

- ^ a b c Gray, Christopher (April 25, 2010). "The U.N.: One Among Many Ideas for the Site". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 27, 2017. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, p. 609.

- ^ a b "Offices" (PDF). Progressive Architecture. Vol. 33. January 1952. p. 110. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 27, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Progressive Architecture 1950, p. 65.

- ^ a b c d Churchill 1952, p. 111.

- ^ ProQuest 1528809947.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Architectural Forum 1950, p. 97.

- ^ from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ ProQuest 1335262986.

- ^ a b c d e Architectural Forum 1950, p. 98.

- ^ from the original on July 25, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ ProQuest 1327505089.

- ^ from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ ProQuest 1327275496.

- ^ from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- from the original on July 25, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Progressive Architecture 1950, p. 64.

- ^ Morrone, Francis (August 8, 2008). "In Midtown, Modernist Perfection in a Glass Box". The New York Sun. Archived from the original on April 19, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ^ OCLC 923852487.

- ^ OCLC 45730295.

- ^ from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ ProQuest 152137673.

- ^ Progressive Architecture 1950, pp. 19, 51.

- ^ a b c d Hughes, C. J. (September 20, 2010). "UN Headquarters Gets $1.8 Billion Facelift". Architectural Record. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Betsky & Murphy 2005, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Churchill 1952, p. 114.

- ^ ISBN 1-56898-181-3.

- ^ "United Nations Headquarters Campus Renovation of Facades". Docomomo. April 27, 2017. Archived from the original on February 3, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ from the original on November 30, 2012. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- from the original on January 15, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, p. 618.

- ^ a b c d Adlerstein 2015, p. 5.

- ^ from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- ^ "United Nations Headquarters Board of Design, Wallace K. Harrison, Max Abramovitz, Oscar Niemeyer, Le Corbusier (Charles-Édouard Jeanneret). Façade from the United Nations Secretariat Building, New York, New York. 1950". The Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ from the original on July 27, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ a b "Window Leaks Overcome" (PDF). Architectural Forum. Vol. 96. January 1952. p. 134. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 27, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ a b c Churchill 1952, p. 113.

- ^ a b c d Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, p. 619.

- ^ ProQuest 1327368232.

- ^ "Art: Cheops' Architect". Time. September 22, 1952. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ProQuest 1326811898.

- ^ ProQuest 152261806.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Vogue 1952, p. 129.

- ^ from the original on July 27, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ UN Chronicle 1977, p. 39.

- from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ ProQuest 1327671994.

- ^ from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- from the original on July 27, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ ProQuest 1335446163.

- ^ a b Betsky & Murphy 2005, p. 135.

- ^ Churchill 1952, pp. 113–114.

- from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e UN Chronicle 1977, p. 36.

- ^ from the original on July 27, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ProQuest 1323167277.

- from the original on July 27, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ Architectural Forum 1950, p. 101.

- from the original on July 27, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ProQuest 133071383.

- ^ from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ a b c Betsky & Murphy 2005, p. 128.

- from the original on July 25, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ a b Betsky & Murphy 2005, p. 21.

- ^ Betsky & Murphy 2005, p. 133.

- ^ a b Progressive Architecture 1950, p. 66.

- ^ a b c d e f g Adlerstein 2015, p. 6.

- ^ from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ ProQuest 1325176377.

- ^ a b Betsky & Murphy 2005, p. 122.

- ^ Betsky & Murphy 2005, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Boland, Ed Jr. (June 8, 2003). "F.Y.I." The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 23, 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, p. 606.

- ^ Betsky & Murphy 2005, p. 12.

- from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ a b c Progressive Architecture 1950, p. 58.

- ^ Adlerstein 2015, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d Betsky & Murphy 2005, p. 13.

- ^ a b Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, p. 607.

- from the original on July 25, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ "Fact Sheet: United Nations Headquarters". United Nations. Archived from the original on November 18, 2010. Retrieved January 6, 2011.

- ^ "Architects Nominated To U.N. Design Board" (PDF). Architectural Record. Vol. 110. March 1947. p. 14. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 25, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ ProQuest 1291212043.

- ^ from the original on July 25, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ a b Iglauer 1947, p. 563.

- ^ a b c d Betsky & Murphy 2005, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, p. 612.

- from the original on July 25, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ProQuest 1291188571.

- ^ a b Adlerstein 2015, pp. 3–4.

- ProQuest 1318024597.

- from the original on July 25, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ from the original on July 25, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- from the original on July 25, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, p. 617.

- ProQuest 165762915.

- ^ ProQuest 508362587.

- ProQuest 1291355744.

- from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ ProQuest 1327415157.

- from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ProQuest 1327421149.

- ProQuest 1327256170.

- ^ from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, pp. 612–613.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, p. 613.

- from the original on July 25, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ProQuest 1335272633.

- from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ProQuest 1327445423.

- from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ProQuest 1324181379.

- from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ProQuest 1326796077.

- from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- ProQuest 1327122137.

- ProQuest 1326781947.

- ProQuest 1766496108.

- from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ProQuest 1766378326.

- ProQuest 1327502658.

- from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved December 25, 2017.

- ^ Associated Press (October 24, 1949). "Dewey Urges UN Power to Enforce Acts" (PDF). Elmira Star-Gazette. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved December 20, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ ProQuest 1326834428.

- ^ ProQuest 508246885.

- ProQuest 1326859409.

- from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- from the original on July 27, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ a b c Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 414.

- from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ProQuest 1335496602.

- ProQuest 1318589487.

- from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ Hamilton, Thomas J. (October 10, 1953). "Work Completed on U.N. Buildings". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 24, 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- from the original on July 27, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ ProQuest 178220886.

- from the original on July 27, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- from the original on July 27, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- from the original on July 27, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- from the original on July 27, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ProQuest 509780163.

- from the original on July 27, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- from the original on December 30, 2018. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ProQuest 547880312.

- from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ProQuest 155554242.

- from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 403.

- ^ from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ProQuest 422028690.

- ^ "U.N. wants aging home in New York fixed soon". Poughkeepsie Journal. June 12, 2005. pp. 14A. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ProQuest 398857148.

- ^ Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, pp. 414–415.

- ^ a b c Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 415.

- from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ "A $1B facelift for UN complex". Newsday. July 28, 2007. p. 7. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ ProQuest 426444158.

- from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ Worsnip, Patrick (May 5, 2008). "U.N. headquarters renovation launched in New York". Reuters. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ a b Adlerstein 2015, p. 4.

- ^ Adlerstein 2015, p. 7.

- ^ "United Nations Capital Master Plan – Timeline". United Nations. August 8, 2012. Archived from the original on September 4, 2012. Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- ^ "Storm Sandy: New York inquiry into overpricing". BBC News. November 5, 2012. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ProQuest 1894134086.

- from the original on July 27, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ProQuest 1319900176.

- ^ a b Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, pp. 618–619.

- ^ a b Betsky & Murphy 2005, p. 22.

- ^ "Art: Cheops' Architect". Time. September 22, 1952. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ Architectural Forum 1950, p. 95.

- from the original on July 27, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ Mumford, Lewis (September 15, 1951). "The Sky Line: Magic with Mirrors—I". The New Yorker. pp. 86, 90. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ Mumford, Lewis (September 22, 1951). "The Sky Line: Magic with Mirrors—II". The New Yorker. pp. 99, 106. Archived from the original on July 27, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ a b "Springs Mills Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. April 13, 2010. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 3, 2019. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ Tyrnauer, Matt (June 14, 2010). "Forever Modern". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on January 28, 2023. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ Horsley, Carter B. (November 30, 1975). "In Glass Walls, a Reflected City Stands Beside the Real One". The New York Times. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Betsky & Murphy 2005, p. 25.

- from the original on July 7, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ Betsky & Murphy 2005, p. 26.

Sources

- Adlerstein, Michael (2015). United Nations Secretariat: Renovation of a Modernist Icon (PDF) (Report). Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat.

- Betsky, Aaron; Murphy, Ben (2005). The U.N. Building. London: Thames & Hudson. OCLC 60667951.

- Churchill, Henry Stern (July 1952). "United Nations Headquarters; A Description and Appraisal" (PDF). Architectural Record. Vol. 112.

- "Features/Articles/People: The UN Secretariat Building". Vogue. Vol. 120, no. 8. November 1, 1952. pp. 125, 1–2, 129, 127-1-1, 127-1-2. ProQuest 879243739.

- Iglauer, Edith (December 1, 1947). "The UN Builds Its Home". Harper's Magazine. Vol. 195, no. 181. ProQuest 1301538833.

- "The Secretariat; A Campanile, a Cliff of Glass, a Great Debate" (PDF). Architectural Forum. Vol. 98. November 1950.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Fishman, David; Tilove, Jacob (2006). New York 2000: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Bicentennial and the Millennium. New York: Monacelli Press. OL 22741487M.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Mellins, Thomas; Fishman, David (1995). New York 1960: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Second World War and the Bicentennial. New York: Monacelli Press. OL 1130718M.

- "U.N. Headquarters Progress Report" (PDF). Progressive Architecture. Vol. 31, no. 6. June 1950.

- "United Nations Headquarters Serves as Meeting Place of World: Construction and Related Costs of Buildings Placed at $73 Million". UN Chronicle. Vol. 14, no. 2. February 1977. ProQuest 1844328210.

External links

Media related to United Nations Secretariat Building at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to United Nations Secretariat Building at Wikimedia Commons