57th Street (Manhattan)

40°45′54″N 73°58′43″W / 40.7649°N 73.9787°W

Apartment buildings lining East 57th Street between First Avenue and Sutton Place | |

| Location | Manhattan, New York City, New York, U.S. |

|---|---|

| West end | West Side Highway |

| East end | York Avenue and Sutton Place |

57th Street is a broad thoroughfare in the

57th Street was created under the Commissioners' Plan of 1811. It was developed as a mainly residential street in the mid-19th century. The central portion of 57th Street was developed as an artistic hub starting in the 1890s, with the development of Carnegie Hall. The section between Fifth and Eighth Avenues is two blocks south of Central Park. Since the early 21st century, the portion of the street south of Central Park has formed part of Billionaires' Row, which contains luxury residential skyscrapers such as 111 West 57th Street, One57, and the Central Park Tower.

Description

Over its two-mile (3 km) length, 57th Street passes through several distinct neighborhoods with differing mixes of commercial, retail, and residential uses.[1] 57th Street is notable for prestigious art galleries,[2] restaurants and up-market shops.

The first block of 57th Street, at its western end at

From Tenth Avenue to

The mid-block between Seventh and Sixth Avenues is a terminus of a north-south pedestrian avenue named Sixth and a Half Avenue.[4]

East of Sixth Avenue, the street is home to numerous high-end retail establishments including Van Cleef & Arpels, Tiffany & Co., and Bergdorf Goodman. The stores located at 57th Street's intersections with Fifth and Madison Avenues occupy some of the most expensive real estate in the world.[5]

Commercial and retail buildings continue to dominate until

57th Street ends at a small city park overlooking the East River just east of Sutton Place.

History

The street was designated by the Commissioners' Plan of 1811 that established the Manhattan street grid as one of 15 east-west streets that would be 100 feet (30 m) in width (while other streets were designated as 60 feet (18 m) in width).[6][7] Throughout its history, 57th Street has contained high-end housing and retail, as well as artistic uses.[8]

Early development

57th Street was laid out and opened in 1857.[9] In the early 19th century, there were industrial concerns clustered around either end of 57th Street, near the Hudson and East Rivers. At the time, the surrounding areas were largely undeveloped except for Central Park two blocks to the north.[10] As late as the 1860s, the area east of Central Park was a shantytown with up to 5,000 squatters.[11] The block of the street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues was still mostly undeveloped and noted for its boulders and deep ravines where squatters lived in shanties.[12][13]

The block between Fifth and Madison Avenues was the first part of 57th Street to see development, when Mary Mason Jones built the "Marble Row" on the eastern side of Fifth Avenue from 57th to 58th Streets between 1868 and 1870.

The intersection of 57th Street and Fifth Avenue was further developed in 1879 with the construction of the Cornelius Vanderbilt II House at the northwest corner.[8] The block of West 57th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues was described as being "the very best in the city" by 1885.[17] One contemporary observer described the block's family homes as "first-class dwelling houses".[18] Another called them "the brown-stone mansions of rich brewers, the François Premier chateaux of bankers, the Gothic palaces of railroad kings".[19] The area to the west contained townhouses, some of which were known as New York City's "choicest" residences. On East 57th Street, there were homes interspersed with structures built for the arts.[8]

Arts hub

An artistic hub developed around the two blocks of West 57th Street from Sixth Avenue to Broadway during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, following the opening of

Following World War I, the block of 57th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues transitioned from residential to commercial as speculators bought and transformed the block's mansions into upscale retail establishments. A real estate specialist was quoted in 1922 as saying 57th Street was "the greatest street in New York".[22] As the transformation to fashionable shopping district proceeded, reporters began referring to the block as "Rue de la Paix of New York" or "the Rue de la Paix of America".[23][24] Furthermore, after about 1921, art galleries started to supplant residences on 57th Street,[11] and other art galleries developed on the street in general.[25] For instance, the Fuller Building at 41 East 57th Street has traditionally contained many galleries since its completion in 1929.[26] During the early 20th century, many of the original townhouses on East 57th Street were rebuilt as art galleries. Interior decorators also moved to the area, converting existing houses or erecting new structures such as the Todhunter Building at 119 East 57th Street.[8]

During the mid-1920s, two major piano showrooms, Chickering Hall and Steinway Hall, were developed on West 57th Street, as was the

Billionaires' Row

Starting in the 2010s, quite a few very tall ultra-luxury residential buildings have been constructed or proposed on the stretch of West 57th Street between Eighth and Park Avenues, which is largely within two blocks of Central Park.[27] The first of these was One57, a 1,004-foot (306 m) apartment building between Sixth and Seventh Avenues, which was completed in 2014.[28] Due to the often record-breaking prices[29][30] that have been set for the apartments in these buildings, the press has dubbed this section of 57th Street as "Billionaires' Row".[31][32][33] These projects have generated controversy concerning the economic conditions[34][35] and zoning policies[36] that have encouraged these buildings, as well as the impact these towers will have on the surrounding neighborhoods and the shadows they will cast on Central Park.[37]

Transportation

The

The

Notable places

- 300 East 57th Street

- The Galleria, 115 East 57th Street[43] Eric Claptons son fell from the building back in 1991.[44]

- Ritz Tower, NE corner of Park Avenue, a New York City designated landmark

- Four Seasons Hotel New York, 57 East 57th Street

- Fuller Building, NE corner of Madison Avenue, a New York City designated landmark

- 590 Madison Avenue

- LVMH Tower

- L. P. Hollander Company Building, 3 East 57th Street, a New York City designated landmark

- Bergdorf Goodman Building, NW corner of Fifth Avenue, a New York City designated landmark

- Formerly: site of Theodore Roosevelt's home in the 1870s and 1880s, 6 West 57th Street[45]

- Solow Building, 9 West 57th Street

- Formerly: Sherwood Studios Building, SE corner of Sixth Avenue

- The Quin

- 111 West 57th Street, a residential tower; incorporating the former Steinway Hall, a New York City designated landmark

- Le Parker Meridien

- 130 West 57th Street, a New York City designated landmark

- 140 West 57th Street, a New York City designated landmark

- Metropolitan Tower, 142 West 57th Street

- Russian Tea Room, 148 West 57th Street

- Carnegie Hall Tower, between Sixth and Seventh Avenues

- One57, 157 West 57th Street

- 165 West 57th Street, campus of the IESE Business School, a New York City designated landmark

- Carnegie Hall, SE corner Seventh Avenue, a New York City designated landmark

- The Briarcliffe, a former hotel at 171 West 57th Street

- Osborne Apartments, NW corner of Seventh Avenue, a New York City designated landmark

- Rodin Studios, SW corner of Seventh Avenue, a New York City designated landmark

- 215 West 57th Street between Seventh Avenue and Broadway, headquarters of the Art Students League of New York, a New York City designated landmark

- 220 West 57th Streetbetween Seventh Avenue and Broadway, a New York City designated landmark

- 224 West 57th Street SE corner of Broadway, a New York City designated landmark

- Central Park Tower, 225 West 57th Street

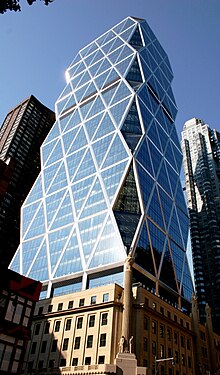

- Hearst Tower, SW corner of Eighth Avenue, a New York City designated landmark

- Windermere Apartments, SW corner of Ninth Avenue, a New York City designated landmark

- Catholic Apostolic Church, 417 West 57th Street, a New York City designated landmark

- CBS Broadcast Center, from Tenth to Eleventh Avenues

- VIA 57 West, 625 West 57th Street

Shopping

The following high-end stores can be found between

|

References

Notes

- .

- ISBN 978-3-86987-200-1.

- ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Grynbaum, Michael M.; Flegenheimer, Matt (July 13, 2012). "Officially Marking a New Manhattan Avenue". City Room. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- . Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- . Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ A History of Real Estate, Building, and Architecture in New York City. New York: Real Estate Record and Guide. 1898. p. 34.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "130 West 57th Street Studio Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 19, 1999. pp. 2–3. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 23, 2021. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ N. Y. Supreme Court; General Term; Nancy L. Sherwood and Mary E. Blodgett, Respondents, vs. The Metropolitan Elevated Railway Company and the Manhattan Railway Company, Appellants. New York: Martin B. Brown. 1890. p. 23.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ ProQuest 1111941344.

- ^ a b James W. Shepp (1894). Shepp's New York City Illustrated. Chicago: Globe Bible Publishing Co. pp. 114–115.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ John Fowler Trow (1876). New York City Directory, 1876/77. New York: The Trow City Directory Co.

- ^ Phillips' élite directory of private families and ladies visiting and shopping guide for New York City. New York: W. Phillips. 1881. p. 360.

- ^ "How the Great Apartment Houses Have Paid". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 35, no. 882. February 7, 1885. pp. 127–128.

- ^ N. Y. Supreme Court; General Term; Nancy L. Sherwood and Mary E. Blodgett, Respondents, vs. The Metropolitan Elevated Railway Company and the Manhattan Railway Company, Appellants. New York: Martin B. Brown. 1890. p. 78.

- ^ "Through the New York Studios". Illustrated American. Vol. 12, no. 131. New York: Illustrated American Publishing Co. August 27, 1892. p. 81.

- ISBN 978-1-60354-055-1. (Reprinted by Scholarly Press, 1976; often referred to as WPA Guide to New York City.)

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ Cushman, J. Clydesdale (March 26, 1922). "Keystone of Uptown Business Section Will Always Be 57th St". New York Herald. p. 74. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ Zeveloff, Julie. "New York's iconic skyline will look incredibly different in just a few years". Business Insider. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ "Justin Davidson on One57 -- New York Magazine Architecture Review - Nymag". New York Magazine. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ "Saudi billionaire said to be buyer of $95M penthouse at 432 Park". The Real Deal New York. May 28, 2015. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Willett, Megan. "The New Billionaires' Row: See The Incredible Transformation Of New York's 57th Street". Business Insider. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul. "New Condo Towers Are Racing Skyward in Midtown Manhattan". Vanity Fair. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Rosenberg, Zoe (March 18, 2015). "New York's Megatower Boom Reduced To Mere 'Vertical Money'". Curbed NY. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ "Why Billionaires Don't Pay Property Taxes in New York". Bloomberg. May 11, 2015. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ "Why 57th Street Is the Supertall Tower Mecca of New York". Curbed NY. September 25, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ "New Yorkers Protest Long Shadows Cast By New Skyscrapers". NPR.org. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ "Subway Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ "Manhattan Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. July 2019. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ "Brooklyn Bus Service" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. October 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ "Queens Bus Service" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 2019. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ "Staten Island Bus Service" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. January 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ "Eric Clapton's Son Killed in Fall". AP NEWS. Retrieved May 7, 2023.

- ^ York, Mailing Address: 28 East 20th Street New; Us, NY 10003 Phone: 212 260-1616 Contact. "The Brownstone Townhouse of Theodore Roosevelt - Theodore Roosevelt Birthplace National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved May 7, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

External links

- Shopping 57th Street by NYC Tourist

- 57th Street: A New York Songline – virtual walking tour