User:MicroMarine/sandboxproject

| Chimaeras Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

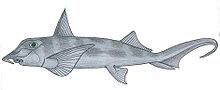

Hydrolagus colliei

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Holocephali |

| Order: | Chimaeriformes Obruchev, 1953 |

| Families | |

| |

Chimaeras

At one time a "diverse and abundant" group (based on the

Description and habits

They have elongated, soft bodies, with a bulky head and a single gill-opening. They grow up to 150 cm (4.9 ft) in length, although this includes the lengthy tail found in some species. In many species, the snout is modified into an elongated sensory organ.[4]

Like other members of the class

Chimaeras resemble sharks in some ways: they employ

They also differ from sharks in that their upper jaws are fused with their skulls and they have separate

Distribution

Chimaeras live in temperate ocean floors down to 2,600 m (8,500 ft) deep, with few occurring at depths shallower than 200 m (660 ft). Exceptions include the members of the

Currently, there are three extant families; Callorhinchidae, Rhinochimaeridae and Chimaeridae. The distribution of each family varies greatly, and may not completely capture all areas that inhabit due to the lack of research [Image showing the distribution of the three extant families would be included here][9].

Growth and reproduction

Unlike 75% of the class of Chondrichthyes that give birth to live young (ovoviviparity and viviparity), Chimaera’s lay their young in eggs (Oviparous), often referred to as Mermaids Purses, which is a leathery case that will hatch in 6-12 months. Additionally, when females lay their eggs, they are paired and remained attached to the female for a period of time before attaching to the seabed[10]. The process of egg-laying takes around 18-30 hours and can occur every 10-14 days throughout the breeding season (which is 6-8 months long), indicating an annual fecundity range of 19.5 - 28.9[8]. Chimaera’s exhibit sexual dimorphism, where males reach sexual maturity after reaching a length of 18.5 - 20 cm, and females reach sexual maturity when they reach a length of 24 - 25 cm[10].

The eggs of the chimera can reach up to 10 cm long. After incubation, the eggs will hatch and young chimera will appear at about roughly 14 cm in length. The chimaera does not have a larval stage as they are fully developed once they hatch[8]. Unlike other sharks, it is hard to age ghost sharks. They lack the hard internal structures which are typically used to age other chondrichthyans. Estimates from various studies and observations place chimaeras with a maximum age estimate of about 40 years[11][12].

Diet

As mentioned in the description and habits section, chimaera, unlike sharks have three pairs of large permanent grinding tooth plates[13]. In addition to this, Chimaeras are not strong swimmer, which further limits their diet to bottom dwelling invertebrates such as crabs, clams, shrimp, and small benthic fish. In addition to small invertebrates, they have been known to eat their own egg cases and even other chimaeras[10].

Phylogenetics

Tracing the evolution of these species has been problematic given the paucity of good fossils. DNA sequencing has become the preferred approach to understanding speciation.[14]

The group containing Chimeras and their close relatives (

Parasites

As other fish, chimaeras have a number of

Threats and Concerns

Climate Change

Climate change can have an effect on chimeras. Because they are deep-sea organisms, there is moderate exposure to climate change factors. This includes rising temperature as this affects their physicochemical environment.[18] The rising sea temperatures could lead to a change in the distribution of the chimaeras. This change in distribution is not yet known [8]. These changes could also affect currents and upwelling which will lead to a negative impact on the productivity in the deep ocean.[18]

By-catch

In addition to climate change, another major threat to chimaeras is overfishing by the means of by-catch, through deep-sea and inshore trawling activities. These activities can threaten the stability of the species population because they're a deep-sea fish which often means they grow at a slower rate and reach reproductive maturity later in life[19].

Classification

In some classifications, the chimaeras are included (as subclass Holocephali) in the class Chondrichthyes of cartilaginous fishes; in other systems, this distinction may be raised to the level of class. Chimaeras also have some characteristics of bony fishes.

A renewed effort to explore deep water and to undertake taxonomic analysis of specimens in museum collections led to a boom during the first decade of the 21st century in the number of new species identified.):

- †Suborder Myriacanthoidei Patterson 1965 (Late Triassic-Late Jurassic)

- †Family Chimaeropsidae

- †Chimaeropsis Zittel 1887 Belgium, Early Jurassic (Sinemurian)

- †Family Myriacanthidae Woodward 1889

- †Acanthorhina Fraas 1910 Posidonia Shale Formation, Germany, Early Jurassic (Toarcian)

- †Agkistracanthus Duffin and Furrer 1981 Austria, England and Switzerland, Late Triassic-Early Jurassic (Rhaetian-Sinemurian)

- †Alethodontus Duffin 1983 Germany, Early Jurassic (Sinemurian)

- †Halonodon Duffin 1984 Belgium and Luxembourg, Early Jurassic (Sinemurian)

- †Metopacanthus Zittel 1887 Posidonia Shale Formation, Germany, Early Jurassic (Toarcian)

- †Oblidens Duffin and Milàn 2017 Hasle Formation, Denmark, Early Jurassic (Pliensbachian)

- †Myriacanthus Agassiz 1837 United Kingdom, Late Triassic-Early Jurassic (Rhaetian-Sinemurian)

- †Recurvacanthus Duffin 1981 United Kingdom, Early Jurassic (Sinemurian)

- †Family Chimaeropsidae

- †Suborder Protochimaeroidei Lebedev & Popov, 2021

- †Family Protochimaeridae Lebedev & Popov, 2021

- †Protochimaera Lebedev & Popov, 2021 Moscow Region, Russia, Lower Carboniferous (Viséan–Serpukhovian)[15]

- †Family Protochimaeridae Lebedev & Popov, 2021

- Suborder Chimaeroidei Patterson 1965

- †Eomanodon Ward and Duffin 1989 United Kingdom, Early Jurassic (Pleinsbachian)

- Family Callorhinchidae Garman, 1901

- Genus Callorhinchus Lacépède, 1798

- Callorhinchus callorynchus Linnaeus, 1758 (ploughnose chimaera)

- A. H. A. Duméril, 1865 (Cape elephantfish)

- Bory de Saint-Vincent, 1823 (Australian ghost shark)

- †Brachymylus A. S. Woodward 1894 Germany, Early Jurassic (Pleinsbachian)

- †Bathytheristes Duffin 1995 Posidonia Shale Formation, Germany, Early Jurassic (Toarcian)

- †Ottangodus Popov, Delsate & Felten, 2019 France, Middle Jurassic (Bajocian)

- Genus Callorhinchus Lacépède, 1798

- Family Chimaeridae Bonaparte, 1831

- Genus Chimaera Linnaeus, 1758

- W. T. White & Pogonoski, 2008 (whitefin chimaera)

- Compagno, 2010 (Bahamas ghost shark)

- Chimaera compacta Iglésias, Kemper & Naylor, 2022[21]

- Chimaera cubana Howell-Rivero, 1936

- W. T. White, 2008 (southern chimaera)

- Chimaera jordani S. Tanaka (I), 1905 (Jordan's chimaera)

- Chimaera lignaria Didier, 2002 (carpenter's chimaera)

- W. T. White, 2008 (longspine chimaera)

- (rabbit fish)

- Compagno & Didier, 2010 Cape chimaera

- W. T. White, 2008 (shortspine chimaera)

- , 2011

- Chimaera owstoni S. Tanaka (I), 1905 (Owston's chimaera)

- Chimaera panthera Didier, 1998 (leopard chimaera)

- , 1900 (silver chimaera)

- Genus Hydrolagus Gill, 1863

- Hydrolagus affinis Brito Capello, 1868 (smalleyed rabbitfish)

- Gilchrist, 1922 (African chimaera)

- , 1951

- , 2006 (whitespot ghost shark)

- Hydrolagus barbouri Garman, 1908

- Hydrolagus bemisi Didier, 2002 (pale ghost shark)

- Hydrolagus colliei Lay & E. T. Bennett, 1839 (spotted ratfish)

- Hydrolagus deani H. M. Smith & Radcliffe, 1912 (Philippine chimaera)

- Hydrolagus eidolon Jordan & Hubbs, 1925

- Hydrolagus homonycteris Didier, 2008 (black ghostshark)

- Hydrolagus lemures Whitley, 1939 (blackfin ghostshark)

- Hydrolagus lusitanicus Moura, Figueiredo, Bordalo-Machado, Almeida & Gordo, 2005

- de Buen, 1959

- Hydrolagus marmoratus Didier, 2008 marbled ghostshark

- Hydrolagus matallanasi Soto & Vooren, 2004 (striped rabbitfish)

- , 2006 (Galápagos ghostshark)

- Hydrolagus melanophasma K. C. James, Ebert, Long & Didier, 2009 (Eastern Pacific black ghostshark)

- Hydrolagus mirabilis Collett, 1904 (large-eyed rabbitfish)

- Hydrolagus mitsukurii Jordan & Snyder, 1904 (spookfish)

- Hydrolagus novaezealandiae Fowler, 1911 (dark ghostshark)

- Hydrolagus ogilbyi Waite, 1898

- Hydrolagus pallidus Hardy & Stehmann, 1990

- Hydrolagus purpurescens Gilbert, 1905 (purple chimaera)

- , 2002 (pointy-nosed blue chimaera)

- Hydrolagus waitei Fowler, 1907

- Genus Chimaera Linnaeus, 1758

- Family Rhinochimaeridae Garman, 1901

- Genus Harriotta Goode & Bean, 1895

- Harriotta haeckeli Karrer, 1972 (smallspine spookfish)

- , 1895 (Pacific longnose chimaera)

- Genus Neoharriotta Bigelow & Schroeder, 1950

- Neoharriotta carri Bullis & J. S. Carpenter, 1966 (dwarf sicklefin chimaera)

- Neoharriotta pinnataSchnakenbeck, 1931 (sicklefin chimaera)

- , 1996 (Arabian sicklefin chimaera)

- Genus Rhinochimaera Garman, 1901

- , 1990 (paddle-nose chimaera)

- Rhinochimaera atlantica Holt& Byrne, 1909 (straightnose rabbitfish)

- Rhinochimaera pacifica Mitsukuri, 1895 (Pacific spookfish)

- Genus Harriotta Goode & Bean, 1895

See also

- List of prehistoric cartilaginous fish

- List of chimaeras

- Acanthothoraci

- Ptyctodontida

References

- ^ a b Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2014). "Chimaeriformes" in FishBase. November 2014 version.

- ^ a b "Ancient And Bizarre Fish Discovered: New Species Of Ghostshark From California And Baja California". ScienceDaily. September 23, 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-23.

- ISBN 0-618-00212-X. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- ^ ISBN 0-12-547665-5.

- ISBN 978-3-642-65926-3.

- ^ Madrigal, Alexis (22 September 2009). "Freaky New Ghostshark ID'd Off California Coast". Wired. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

... Perhaps the most intriguing feature of the newly described species, Hydrolagus melanophasma, is a presumed sexual organ that extends from its forehead called a tentaculum. ...

- ^ Devocean, Shark (2014-08-26). "Introducing: Chimaeras". Shark Devocean. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- ^ )

- ^ "IUCN Red List".

- ^ a b c Pacific, Aquarium of the. "Spotted Ratfish". www.aquariumofpacific.org. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- ISSN 0250-6408.

- )

- )

- PMID 20551041. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ S2CID 239509836.

- S2CID 128402250.

- S2CID 198423356.

- ^ .

- ISSN 0137-1592.

- S2CID 229433827.

- ^ Iglésias, S.P., Kemper, J.M. & Naylor, G.J.P. Chimaera compacta, a new species from southern Indian Ocean, and an estimate of phylogenetic relationships within the genus Chimaera (Chondrichthyes: Chimaeridae). Ichthyol Res 69, 31–45 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10228-021-00810-9