User:Mr. Ibrahem/Kerala

History

Traditional sources

According to the Sangam classic

Another much earlier

Ophir

- 1 Kings22:48

- ^ Book of Job 22:24; 28:16; Psalms 45:9; Isaiah 13:12

Cheraman Perumals

The legend of Cheraman Perumals is the medieval tradition associated with the Cheraman Perumals (literally the

According to the

Pre-history

A substantial portion of Kerala including the western coastal lowlands and the plains of the midland may have been under the sea in ancient times. Marine fossils have been found in an area near

Ancient period

Kerala has been a major spice exporter since 3000 BCE, according to

The Land of Keralaputra was one of the four independent kingdoms in southern India during Ashoka's time, the others being

According to the

Merchants from West Asia and Southern Europe established coastal posts and settlements in Kerala.

Early medieval period

The inhibitions, caused by a series of Chera-Chola wars in the 11th century, resulted in the decline of foreign trade in Kerala ports. In addition, Portuguese invasions in the 15th century caused two major religions,

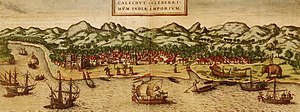

At the peak of their reign, the Zamorins of Kozhikode ruled over a region from Kollam (

The king Deva Raya II (1424–1446) of the Vijayanagara Empire conquered about the whole of present-day state of Kerala in the 15th century.[100] He defeated the Zamorin of Kozhikode, as well as the ruler of Kollam around 1443.[100] Fernão Nunes says that the Zamorin had to pay tribute to the king of Vijayanagara Empire.[100] Later Kozhikode and Venad seem to have rebelled against their Vijayanagara overlords, but Deva Raya II quelled the rebellion.[100] As the Vijayanagara power diminished over the next fifty years, the Zamorin of Kozhikode again rose to prominence in Kerala.[100] He built a fort at Ponnani in 1498.[100]

Late medieval period

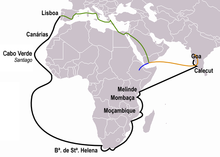

The maritime

The ruler of the

The Portuguese took advantage of the rivalry between the Zamorin and the King of Kochi allied with Kochi. When

In 1571, the Portuguese were defeated by the Zamorin forces in the

In 1602, the Zamorin sent messages to Aceh promising the Dutch a fort at Kozhikode if they would come and trade there. Two factors, Hans de Wolff and Lafer, were sent on an Asian ship from Aceh, but the two were captured by the chief of Tanur, and handed over to the Portuguese.[122] A Dutch fleet under Admiral Steven van der Hagen arrived at Kozhikode in November 1604. It marked the beginning of the Dutch presence in Kerala and they concluded a treaty with Kozhikode on 11 November 1604, which was also the first treaty that the Dutch East India Company made with an Indian ruler.[60] By this time the kingdom and the port of Kozhikode was much reduced in importance.[122] The treaty provided for a mutual alliance between the two to expel the Portuguese from Malabar. In return the Dutch East India Company was given facilities for trade at Kozhikode and Ponnani, including spacious storehouses.[122]

The Portuguese were ousted by the

British era

The island of Dharmadom near Kannur, along with Thalassery, was ceded to the East India Company in 1734, which were claimed by all of the Kolattu Rajas, Kottayam Rajas, and Arakkal Bibi in the late medieval period, where the British initiated a factory and English settlement following the cession.[134][91] In 1761, the British captured Mahé, and the settlement was handed over to the ruler of Kadathanadu.[135] The British restored Mahé to the French as a part of the 1763 Treaty of Paris.[135] In 1779, the Anglo-French war broke out, resulting in the French loss of Mahé.[135] In 1783, the British agreed to restore to the French their settlements in India, and Mahé was handed over to the French in 1785.[135]

In 1757, to resist the invasion of the

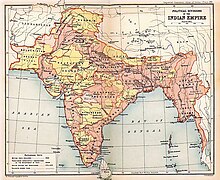

By the end of 18th century, the whole of Kerala fell under the control of the British, either administered directly or under

Post-colonial period

After India was

- ^ ISBN 978-8126421992.

- ^ Ancient Indian History By Madhavan Arjunan Pillai, p. 204 [ISBN missing]

- ^ S.C. Bhatt, Gopal K. Bhargava (2006) "Land and People of Indian States and Union Territories: Volume 14.", p. 18

- ^ Aiya VN (1906). The Travancore State Manual. Travancore Government Press. pp. 210–12. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- ISBN 978-8120601451.

- ISBN 978-1576079058. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ISBN 978-0791453254. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ISBN 978-0199912551. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ISBN 978-0143414216. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ISBN 978-1417944637. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ^ "Ophir". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Schroff, Wifred H. (1912), The Periplus of the Erythræan Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean, New York: Longmans, Green, and Company, p. 41

- ^ Smith, William, A dictionary of the Bible, Hurd and Houghton, 1863 (1870), p. 1441

- ^ Smith's Bible Dictionary

- ^ Ramaswami, Sastri, The Tamils and their culture, Annamalai University, 1967, p. 16

- ^ Gregory, James, Tamil lexicography, M. Niemeyer, 1991, p. 10

- ^ Fernandes, Edna, The last Jews of Kerala, Portobello, 2008, p. 98

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, Ninth Edition, Volume I Almug Tree Almunecar→ALMUG or ALGUM TREE. The Hebrew words Almuggim or Algummim have translated Almug or Algum trees in our version of the Bible (see 1 Kings x. 11, 12; 2 Chron. ii. 8, and ix. 10, 11). The wood of the tree was very precious, and was brought from Ophir (probably some part of India), along with gold and precious stones, by Hiram, and was used in the formation of pillars for the temple at Jerusalem, and for the king's house; also for the inlaying of stairs, as well as for harps and psalteries. It is probably the red sandal-wood of India (Pterocarpus santalinus). This tree belongs to the natural order Leguminosæ, sub-order Papilionaceæ. The wood is hard, heavy, close-grained, and of fine red colour. It is different from the white fragrant sandal-wood, which is the produce of Santalum album, a tree belonging to a distinct natural order. Also, see notes by George Menachery in the St. Thomas Christian Encyclopaedia of India, Vol. 2 (1973)

- ^ Menon, A. Sreedhara (1967), A Survey of Kerala History, Sahitya Pravarthaka Co-operative Society [Sales Department]; National Book Stall, p. 58

- ISBN 978-8120618503

- ^ a b Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 31–32.

- ^ Kesavan Veluthat, ‘The Keralolpathi as History’, in The Early Medieval in South India, New Delhi, 2009, pp. 129–46.

- ^ a b Noburu Karashima (ed.), A Concise History of South India: Issues and Interpretations. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2014. 146–47.

- ^ a b c Frenz, Margret. 2003. ‘Virtual Relations, Little Kings in Malabar’, in Sharing Sovereignty. The Little Kingdom in South Asia, eds Georg Berkemer and Margret Frenz, pp. 81–91. Berlin: Zentrum Moderner Orient.

- ^ a b c Logan, William. Malabar. Madras: Government Press, Madras, 1951 (reprint). 223–40.

- ISBN 978-1136704918. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-9385505638. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ISBN 978-8190250511.

- ISBN 978-1136704918.

- ISBN 817648170-X

- ^ Prange, Sebastian R. Monsoon Islam: Trade and Faith on the Medieval Malabar Coast. Cambridge University Press, 2018. p. 98. [ISBN missing]

- ^ History of Travancore by Shangunny Menon, page 63

- ^ Nainar, S. Muhammad Hussain (1942). Tuhfat-al-Mujahidin: An Historical Work in The Arabic Language. University of Madras.

- ISBN 978-0520213234.

- ISBN 978-8126415786. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ "Unlocking the secrets of history". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 6 December 2004. Archived from the original on 26 January 2005. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ISBN 978-8177552577. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ "Wayanad". kerala.gov.in. Government of Kerala. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ISBN 978-8186565445. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ISBN 978-8186565445. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ISBN 978-8186565445. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ "Symbols akin to Indus valley culture discovered in Kerala". The Hindu. 29 September 2009. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ Pradeep Kumar, Kaavya (28 January 2014). "Of Kerala, Egypt, and the Spice link". The Hindu. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

ChattopadhyayFranke2006was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ ISBN 978-8126415786. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ISBN 978-1605204925. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ The Cambridge Shorter History of India. CUP Archive. p. 193. GGKEY:2W0QHXZ7K40. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ISBN 978-8172110598. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ISBN 978-8120601505. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- ^ Subramanian, T. S (28 January 2007). "Roman connection in Tamil Nadu". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 19 September 2013. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ISBN 978-8126415786. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ISBN 978-8131716779. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ISBN 978-9380607344.

- ^ Singh 2008, p. 385.

- ISBN 978-0819601438. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- ^ Coastal Histories: Society and Ecology in Pre-modern India, Yogesh Sharma, Primus Books 2010

- ISBN 978-8170418597. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ISBN 978-8172110529. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ Gurukkal, R., & Whittaker, D. (2001). In search of Muziris. Journal of Roman Archaeology, 14, 334–350.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Cite error: The named reference

Malabarwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ According to Pliny the Elder, goods from India were sold in the Empire at 100 times their original purchase price. See [1]

- ^ Bostock, John (1855). "26 (Voyages to India)". Pliny the Elder, The Natural History. London: Taylor and Francis.

- ^ Indicopleustes, Cosmas (1897). Christian Topography. 11. United Kingdom: The Tertullian Project. pp. 358–373.

- ^ Das, Santosh Kumar (2006). The Economic History of Ancient India. Genesis Publishing Pvt Ltd. p. 301.

- ^ Cyclopaedia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia. Archived 27 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine Ed. by Edward Balfour (1871), Second Edition. Volume 2. p. 584.

- ^ Joseph Minattur. "Malaya: What's in the name" (PDF). siamese-heritage.org. p. 1. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-8170990260. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ISBN 978-0670084784. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ISBN 978-8120601451. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ISBN 978-8120601451. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ISBN 978-9652781796.

- ^ David D'Beth Hillel (1832). The Travels of Rabbi David D'Beth Hillel: From Jerusalem, Through Arabia, Koordistan, Part of Persia, and Indudasam (India) to Madras. author. p. 135.

- ISBN 978-0837126159.

- ISBN 978-0802824172.

- ISBN 978-0195138863. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ * Bindu Malieckal (2005) Muslims, Matriliny, and A Midsummer Night's Dream: European Encounters with the Mappilas of Malabar, India; The Muslim World Volume 95 Issue 2

- ISBN 978-0521212588.

- ISBN 978-0521891035. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ISBN 978-0765601049. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ISBN 978-0520213234. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ISBN 978-8120811584.

- ISBN 9783447059374.

- ^ M. T. Narayanan (2003). Agrarian Relations in Late Medieval Malabar. Northern Book Centre.

- ^ a b K. Balachandran Nayar (1974). In quest of Kerala. Accent Publications. p. 86. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ISBN 978-8126415786. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-8126415786. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ISBN 978-1136100840.

- ^ "Kollam Era" (PDF). Indian Journal History of Science. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ Broughton Richmond (1956), Time measurement and calendar construction, p. 218

- ^ R. Leela Devi (1986). History of Kerala. Vidyarthi Mithram Press & Book Depot. p. 408.

- ^ ISBN 978-8120604476.

- ISBN 9788126419395.

- ^ Razak, Abdul (2013). Colonialism and community formation in Malabar: a study of Muslims of Malabar.

- ISBN 978-9004079298. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ISBN 978-8171545797. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ISBN 978-3447059374.

- ^ "The Buddhist History of Kerala". Kerala.cc. Archived from the original on 21 March 2001. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ISBN 978-8126415786. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ The Portuguese, Indian Ocean and European Bridgeheads 1500–1800. Festschrift in Honour of Prof. K. S. Mathew (2001). Edited by: Pius Malekandathil and T. Jamal Mohammed. Fundacoa Oriente. Institute for Research in Social Sciences and Humanities of MESHAR (Kerala)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m K. V. Krishna Iyer, Zamorins of Calicut: From the earliest times to AD 1806. Calicut: Norman Printing Bureau, 1938.

- ^ a b c d Varier, M. R. Raghava. "Documents of Investiture Ceremonies" in K. K. N. Kurup, Edit., "India's Naval Traditions". Northern Book Centre, New Delhi, 1997

- ^ Ibn Battuta, H. A. R. Gibb (1994). The Travels of Ibn Battuta A.D 1325–1354. Vol. IV. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ISBN 9748496783

- ^ Varthema, Ludovico di, The Travels of Ludovico di Varthema, A.D.1503–08, translated from the original 1510 Italian ed. by John Winter Jones, Hakluyt Society, London

- ^ Gangadharan. M., The Land of Malabar: The Book of Barbosa (2000), Vol II, M.G University, Kottayam.

- ISBN 978-1568362496.

- ISBN 978-9057024535. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- ISBN 978-0521269315.

- ^ Sanjay Subrahmanyam, The Career and Legend of Vasco da Gama, Cambridge University Press, 1997, 288

- ^ Knox, Robert (1681). An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon. London: Reprint. Asian Educational Services. pp. 19–47.

- ^ "Kollam – Kerala Tourism". Kerala Tourism. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ S. Muhammad Hussain Nainar (1942). Tuhfat-al-Mujahidin: An Historical Work in The Arabic Language. University of Madras.

- ISBN 978-1932705546. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ "Kollam Mayor inspects Tangasseri Fort". The Hindu. 1 February 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ Singh, Arun Kumar (11 February 2017). "Give Indian Navy its due". The Asian Age. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ a b A. Sreedhara Menon. Kerala History and its Makers. D C Books (2011)

- ^ A G Noorani. Islam in Kerala. Books [2]

- ^ a b Roland E. Miller. Mappila Muslim Culture SUNY Press, 2015

- ISBN 978-8172110833. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ISBN 978-8120615243.

- ^ "A Portion of Kasaragod's Bekal Forts Observation Post Caves in". The Hindu. 12 August 2019.

- ^ a b c Sanjay Subrahmanyam. "The Political Economy of Commerce: Southern India 1500–1650". Cambridge University Press, 2002

- ISBN 978-1857433180. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ "How the Portuguese used Hindu-Muslim wars – and Christianity – for the bloody conquest of Goa". Dailyo.in. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

d_1664was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ISBN 978-8172110529. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-9004168169. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8185381428. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-9073782921. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8126421565. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- ISBN 978-1615302024. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ "The Territories and States of India" (PDF). Europa. 2002. pp. 144–46. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ Shungoony Menon, P. (1878). A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times (pdf). Madras: Higgin Botham & Co. pp. 162–164. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ Charles Alexander Innes (1908). Madras District Gazetteers Malabar (Volume-I). Madras Government Press. p. 451.

- ^ a b c d "History of Mahé". Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ISBN 978-8187139690. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-0714124247. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8131758304. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ The Edinburgh Gazetteer. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green. 1827. pp. 63–. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Dharma Kumar (1965). Land and Caste in South India: Agricultural Labor in the Madras Presidency During the Nineteenth Century. CUP Archive. pp. 87–. GGKEY:T72DPF9AZDK. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-8170170341. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Superintendent of Government Printing (1908). Imperial Gazetteer of India (Provincial Series): Madras. Calcutta: Government of India. p. 22. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- ^ Kakkadan Nandanath Raj; Michael Tharakan; Rural Employment Policy Research Programme (1981). Agrarian reform in Kerala and its impact on the rural economy: a preliminary assessment. International Labour Office. pp. 2–3. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

{{cite book}}:|author3=has generic name (help) - ^ "Chronological List of Central Acts (Updated up to 17-10-2014)". Lawmin.nic.in. Retrieved 2016-08-07.

- ^ Lewis McIver, G. Stokes (1883). Imperial Census of 1881 Operations and Results in the Presidency of Madras ((Vol II) ed.). Madras: E.Keys at the Government Press. p. 444. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ Presidency, Madras (India (1915). Madras District Gazetteers, Statistical Appendix For Malabar District (Vol.2 ed.). Madras: The Superintendent, Government Press. p. 20. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ Henry Frowde, M.A., Imperial Gazetteer of India (1908–1909). Imperial Gazetteer of India (New ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ KP Saikiran (10 October 2020). "Beating the retreat: The Malabar Special Police is no longer the trigger-happy unit". The Times of India. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ L.K.A.Iyer, The Mysore Tribes and caste. Vol.III, A Mittal Publish. Page.279, Google Books

- ^ Nagendra k.r.singh Global Encyclopedia of the South India Dalit's Ethnography (2006) page.230, Google Books

- ^ L.Krishna Anandha Krishna Iyer(Divan Bahadur) The Cochin Tribes and Caste Vol.1. Johnson Reprint Corporation, 1962. Page. 278, Google Books

- ^ Iyer, L. K. Anantha Krishna (1909). The Cochin tribes and castes vol.I. Higginbotham, Madras.

- ISBN 978-9004113718.

- ^ Tottenham GRF (ed), The Mappila Rebellion 1921–22, Govt Press Madras 1922 P 71

- ISBN 978-9004045101. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ISBN 978-0143102748. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ "The States Reorganisation Act, 1956" (PDF). legislative.gov.in. Government of India.

- ISBN 978-0520046672.

- ^ ISBN 978-1741791556. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ K.G. Kumar (12 April 2007). "50 years of development". The Hindu. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ISBN 978-0203967744. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ISBN 978-8170248361. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Encyclopædiawas invoked but never defined (see the help page).