Valvular heart disease

| Valvular heart disease | |

|---|---|

| |

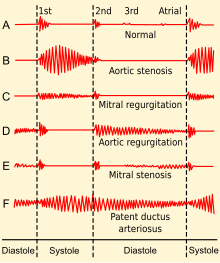

| Phonocardiogram of normal and abnormal heartbeats. | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

| Diagnostic method | Chest radiograph |

Valvular heart disease is any

Anatomically, the valves are part of the dense connective tissue of the heart known as the

Classification

Stenosis and insufficiency/regurgitation represent the dominant functional and anatomic consequences associated with valvular heart disease. Irrespective of disease process, alterations to the valve occur that produce one or a combination of these conditions. Insufficiency and regurgitation are synonymous terms that describe an inability of the valve to prevent backflow of blood as leaflets of the valve fail to join (coapt) correctly. Stenosis is characterized by a narrowing of the valvular orifice that prevents adequate outflow of blood. Stenosis can also result in insufficiency if thickening of the annulus or leaflets results in inappropriate leaf closure.[3]

| Valve involved | Stenotic disease | Insufficiency/regurgitation disease |

| Aortic valve | Aortic valve stenosis

|

Aortic insufficiency /regurgitation

|

| Mitral valve | Mitral valve stenosis

|

Mitral insufficiency /regurgitation

|

| Tricuspid valve | Tricuspid valve stenosis | Tricuspid insufficiency /regurgitation

|

| Pulmonary valve | Pulmonary valve stenosis | Pulmonary insufficiency /regurgitation

|

Aortic and mitral valve disorders

Aortic and mitral valve disorders are

Stenosis of the aortic valve is characterized by a thickening of the valvular annulus or leaflets that limits the ability of blood to be ejected from the left ventricle into the aorta. Stenosis is typically the result of valvular calcification but may be the result of a congenitally malformed bicuspid aortic valve. This defect is characterized by the presence of only two valve leaflets. It may occur in isolation or in concert with other cardiac anomalies.[5]

Aortic insufficiency, or regurgitation, is characterized by an inability of the valve leaflets to appropriately close at the end

Mitral stenosis is caused largely by rheumatic heart disease, though is rarely the result of calcification. In some cases, vegetations form on the mitral leaflets as a result of endocarditis, an inflammation of the heart tissue. Mitral stenosis is uncommon and not as age-dependent as other types of valvular disease.[1]

Mitral insufficiency can be caused by dilation of the left heart, often a consequence of heart failure. In these cases, the left ventricle of the heart becomes enlarged and causes displacement of the attached papillary muscles, which control the mitral.[7]

Pulmonary and tricuspid valve disorders

Pulmonary and tricuspid valve diseases are

Pulmonary valve stenosis is often the result of congenital malformations and is observed in isolation or as part of a larger pathologic process, as in Tetralogy of Fallot, Noonan syndrome, and congenital rubella syndrome. Unless the degree of stenosis is severe, individuals with pulmonary stenosis usually have excellent outcomes and better treatment options. Often patients do not require intervention until later in adulthood as a consequence of calcification that occurs with aging.[citation needed]

Pulmonary valve insufficiency occurs commonly in healthy individuals to a very mild extent and does not require intervention.[8] More appreciable insufficiency is typically the result of damage to the valve due to cardiac catheterization, intra-aortic balloon pump insertion, or other surgical manipulations. Additionally, insufficiency may be the result of carcinoid syndrome, inflammatory processes such a rheumatoid disease or endocarditis, or congenital malformations.[9][10] It may also be secondary to severe pulmonary hypertension.[11]

Tricuspid valve stenosis without co-occurrent regurgitation is highly uncommon and typically the result of rheumatic disease. It may also be the result of congenital abnormalities, carcinoid syndrome, obstructive right atrial tumors (typically lipomas or myxomas), or hypereosinophilic syndromes.[citation needed]

Minor tricuspid insufficiency is common in healthy individuals.

Signs and symptoms

Aortic stenosis

Symptoms of

Medical signs of aortic stenosis include pulsus parvus et tardus, that is, diminished and delayed

Aortic regurgitation

Patients with

Medical signs of aortic regurgitation include increased

Mitral stenosis

Patients with

On

Mitral regurgitation

Patients with

On auscultation of a patient with mitral stenosis, there may be a

Tricuspid regurgitation

Patients with

Signs of tricuspid regurgitation include

Causes

Calcific disease

Dysplasia

Heart valve dysplasia is an error in the development of any of the heart valves, and a common cause of congenital heart defects in humans as well as animals; tetralogy of Fallot is a congenital heart defect with four abnormalities, one of which is stenosis of the pulmonary valve. Ebstein's anomaly is an abnormality of the tricuspid valve, and its presence can lead to tricuspid valve regurgitation.[16][18] A bicuspid aortic valve[16] is an aortic valve with only 2 cusps as opposed to the normal 3. It is present in about 0.5% to 2% of the general population and causes increased calcification due to higher turbulent flow through the valve.[17]

Connective tissue disorders

Marfan's Syndrome is a connective tissue disorder that can lead to chronic aortic or mitral regurgitation.[16] Osteogenesis imperfecta is a disorder in formation of type I collagen and can also lead to chronic aortic regurgitation.[16]

Inflammatory disorders

Inflammation of the heart valves due to any cause is called valvular

Valvular heart disease resulting from

In 70% of cases rheumatic heart disease involves only the mitral valve, while 25% of cases involve both the aortic and mitral valves. Involvement of other heart valves without damage to the mitral is exceedingly rare.[23] Mitral stenosis is almost always caused by rheumatic heart disease.[16] Less than 10% of aortic stenosis is caused by rheumatic heart disease.[15][16] Rheumatic fever can also cause chronic mitral and aortic regurgitation.[16]

While developed countries once had a significant burden of rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease, medical advances and improved social conditions have dramatically reduced their incidence. Many developing countries, as well as indigenous populations within developed countries, still carry a significant burden of rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease

Diseases of the aortic root can cause chronic aortic regurgitation. These diseases include syphilitic aortitis, Behçet's disease, and reactive arthritis.[16]

Heart disease

Tricuspid regurgitation is usually secondary to right ventricular dilation

Diagnosis

Aortic stenosis

Patients with

| Classification | Valve area |

|---|---|

| Mild aortic stenosis | 1.5-2.0 cm2 |

| Moderate aortic stenosis | 1.0-1.5 cm2 |

| Severe aortic stenosis | <1.0 cm2 |

Aortic regurgitation

Mitral stenosis

Mitral regurgitation

Treatment

Some of the most common treatments of valvular heart disease are avoiding smoking and excessive alcohol consumption, antibiotics, antithrombotic medications such as aspirin, anticoagulants, balloon dilation, and water pills.[34] In some cases, surgery may be necessary.

Aortic stenosis

Treatment of aortic stenosis is not necessary in asymptomatic patients, unless the stenosis is classified as severe based on valve hemodynamics.

Aortic regurgitation

Mitral stenosis

For patients with symptomatic severe mitral stenosis, percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty (PBMV) is recommended.[8] If this procedure fails, then it may be necessary to undergo mitral valve surgery, which may involve valve replacement, repair, or commisurotomy.[8] Anticoagulation is recommended for patients that have mitral stenosis in the setting of atrial fibrillation or a previous embolic event.[8] No therapy is required for asymptomatic patients. Diuretics may be used to treat pulmonary congestion or edema.[16]

Mitral regurgitation

Surgery is recommended for chronic severe mitral regurgitation in symptomatic patients with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of greater than 30%, and asymptomatic patients with LVEF of 30-60% or left ventricular end diastolic volume (LVEDV) > 40%.[8] Surgical repair of the leaflets is preferred to mitral valve replacement as long as the repair is feasible.[8] Mitral regurgitation may be treated medically with vasodilators, diuretics, digoxin, antiarrhythmics, and chronic anticoagulation.[15][16] Mild to moderate mitral regurgitation should be followed with echocardiography and cardiac stress test every 1–3 years.[15] Severe mitral regurgitation should be followed with echocardiography every 3–6 months.[15]

Epidemiology

In the United States, about 2.5% of the population has moderate to severe valvular heart disease.[39] The prevalence of these diseases increase with age, and 75 year-olds in the United States have a prevalence of about 13%.[39] In industrially underdeveloped regions, rheumatic disease is the most common cause of valve diseases, and it can cause up to 65% of the valve disorders seen in these regions.[39]

Aortic stenosis

Aortic stenosis is typically the result of aging, occurring in 12.4% of the population over 75 years of age, and represents the most common cause of outflow obstruction in the left ventricle.[1] Bicuspid aortic valves are found in up to 1% of the population, making it one of the most common cardiac abnormalities.[40]

Aortic regurgitation

The prevalence of aortic regurgitation also increases with age. Moderate to severe disease has a prevalence of 13% in patients between the ages of 55 and 86.[39] This valve disease is primarily caused by aortic root dilation, but infective endocarditis has been an increased risk factor. It has been found to be the cause of aortic regurgitation in up to 25% of surgical cases.[39]

Mitral stenosis

Mitral regurgitation

Mitral regurgitation is significantly associated with normal aging, rising in prevalence with age. It is estimated to be present in over 9% of people over 75.[1]

Special populations

Pregnancy

The evaluation of individuals with valvular heart disease who are or wish to become

Valvular heart lesions associated with high maternal and fetal risk during pregnancy include:[42]

- Severe aortic stenosis with or without symptoms

- Aortic regurgitation with NYHAfunctional class III-IV symptoms

- Mitral stenosis with NYHA functional class II-IV symptoms

- Mitral regurgitation with NYHA functional class III-IV symptoms

- Aortic and/or mitral valve disease resulting in severe pulmonary hypertension (pulmonary pressure greater than 75% of systemic pressures)

- Aortic and/or mitral valve disease with severe LV dysfunction (EF less than 0.40)

- Mechanical prosthetic valve requiring anticoagulation

- Marfan syndrome with or without aortic regurgitation

In individuals who require an artificial heart valve, consideration must be made for deterioration of the valve over time (for bioprosthetic valves) versus the risks of blood clotting in pregnancy with mechanical valves with the resultant need of drugs in pregnancy in the form of anticoagulation.[citation needed]

References

- ^ a b c d e Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study. Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, Gottdiener JS, Scott CG, Enriquez-Sarano. Lancet. 2006 Sep;368(9540):1005-11.

- ^ Pregnancy and contraception in congenital heart disease: what women are not told. Kovacs AH, Harrison JL, Colman JM, Sermer M, Siu SC, Silversides CK J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(7):577.

- PMID 27325921.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link - ^ a b Ragavendra R. Baliga, Kim A. Eagle, William F Armstrong, David S Bach, Eric R Bates, Practical Cardiology, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008, page 452.

- ^ a b "Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. 28 September 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ISBN 0-7817-7153-6.

- ^ "Mitral Regurgitation". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP 3rd, Guyton RA, O'Gara PT, Ruiz CE, Skubas NJ, Sorajja P, Sundt TM 3rd, Thomas JD. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(22):e57.

- ^ Isolated pulmonic valve infective endocarditis: a persistent challenge.[citation needed] Hamza N, Ortiz J, Bonomo. Infection. 2004 Jun;32(3):170-5.

- ^ Carcinoid heart disease. Clinical and echocardiographic spectrum in 74 patients. Pellikka PA, Tajik AJ, Khandheria BK, Seward JB, Callahan JA, Pitot HC, Kvols LK. Circulation. 1993;87(4):1188.

- ^ "What Is Pulmonary Hypertension?". NHLBI – NIH. 2 August 2011. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- Zoghbi WA, Enriquez-Sarano M, Foster E, Grayburn PA, Kraft CD, Levine RA, Nihoyannopoulos P, Otto CM, Quinones MA, Rakowski H, Stewart WJ, Waggoner A, Weissman NJ, American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2003;16(7):777.

- ^ Impact of tricuspid regurgitation on long-term survival. Nath J, Foster E, Heidenreich PA. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(3):405.

- ^ "Facts About Critical Congenital Heart Defects | NCBDDD | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2017-06-27. Retrieved 2017-10-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w VOC=VITIUM ORGANICUM CORDIS, a compendium of the Department of Cardiology at Uppsala Academic Hospital. By Per Kvidal September 1999, with revision by Erik Björklund May 2008

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7817-7153-5.

- ^ a b Owens DS, O'Brien KD. Clinical and Genetic Risk Factors for Calcific Valve Disease. In: Valvular Heart Disease, 4th, Otto CM, Bonow RO. (Eds), Saunders/Elsevier, Philadelphia 2013. pp.53-62.

- PMID 16880336.

- "Correction". Circulation. 115 (15). 2007.

- "Correction". Circulation. 121 (23). 2010. .

- PMID 17202453.

- ^ National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Division of Bacterial Diseases (27 June 2022). "Acute Rheumatic Fever". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ISBN 978-0323757485.

- PMID 31373269.

- ^ a b Vinay, Kumar (2013). Robbin's Basic Pathology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. Chapter 10: Heart.

- ^ "Rheumatic heart disease". Heart & Stroke. Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. 2022.

- ^ "Rheumatic heart disease". University of Cape Town Pathology Learning Centre. 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ AIHW. "Australia's health 2020: data insights". Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Government. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ "Rheumatic Heart Disease". World Health Organization. 6 November 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- PMID 35049336. e024517.

- ^ a b c Rosenhek R, Baumgartner H. Aortic Stenosis. In: Valvular Heart Disease, 4th, Otto CM, Bonow RO. (Eds), Saunders/Elsevier, Philadelphia 2013. pp 139-162.

- ^ OCLC 1029074059.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ^ ISBN 978-1-259-64403-0. OCLC1029074059.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-259-64403-0. OCLC1029074059.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-259-64403-0. OCLC1029074059.

- ^ "Heart Valve Disease". National Heart, Lung And Blood Institute. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- PMID 38331412.

- PMID 28315732.

- PMID 35171199.

- PMID 36915288.

- ^ a b c d e f Chambers, John B.; Bridgewater, Ben (2014). Otto, CM; Bonow, RO (eds.). Epidemiology of Valvular Heart Disease (4th ed.). Saunders. pp. 1–13.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Braverman AC. The Bicuspid Aortic Valve and Associated Aortic Disease. In: Valvular Heart Disease, 4th, Otto CM, Bonow RO. (Eds), Saunders/Elsevier, Philadelphia 2013. p.179.

- PMID 18007005.

- ^ PMID 18848134.