American rock

American rock has its roots from 1940s and 1950s rock and roll, rhythm and blues, and country music, and also draws from folk music, jazz, blues, and classical music. American rock music was further influenced by the British Invasion of the American pop charts from 1964 and resulted in the development of psychedelic rock.

From the late 1960s and early 1970s, American rock music was highly influential in the development of a number of fusion genres, including blending with folk music to create folk rock, with blues to create blues rock, with country music to create country rock, roots rock and Southern rock and with jazz to create jazz rock, all of which contributed to psychedelic rock. In the 1970s, rock developed a large number of subgenres, such as soft rock, hard rock, heavy metal, glam rock, progressive rock and punk rock.

New subgenres that were derived from punk and important in the 1980s included

Rock and roll (1950s to early 1960s)

Origins

The foundations of American rock music are in rock and roll, which originated in the United States in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Its immediate origins lay in a mixing together of various black musical genres of the time, including rhythm and blues and gospel music; in addition to country and western.[1] In 1951, Cleveland disc jockey Alan Freed began playing rhythm and blues music for a multi-racial audience, and is credited with first using the phrase "rock and roll" to describe the music.[2]

There is much debate as to what should be considered the

Diversification

Rock and roll has been seen as leading to a number of distinct subgenres, including

"Decline"

Commentators have traditionally perceived a decline of rock and roll in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Surf music

The instrumental rock and roll pioneered by performers such as

Surf music achieved its greatest commercial success as vocal music, particularly the work of the

Development (mid-to-late 1960s)

The British Invasion

By the end of 1962 British beat groups like The Beatles were drawing on a wide range of American influences including soul music, rhythm and blues and surf music.[28] Initially, they reinterpreted standard American tunes, playing for dancers doing the twist, for example. These groups eventually infused their original compositions with increasingly complex musical ideas and a distinctive sound. During 1963, The Beatles and other beat groups, such as The Searchers and The Hollies, achieved popularity and commercial success in Britain.[29]

British rock broke through to mainstream popularity in the United States in January 1964 with the success of the Beatles. "I Want to Hold Your Hand" was the band's first number 1 hit on the Billboard Hot 100 chart, starting the British Invasion of the American music charts.[30] The song entered the chart on January 18, 1964, at number 45 before it became the number 1 single for 7 weeks and went on to last a total of 15 weeks in the chart.[31] Their first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show February 9 is considered a milestone in American pop culture.[32] The broadcast drew an estimated 73 million viewers, at the time a record for an American television program. The Beatles went on to become the biggest selling rock band of all time and they were followed by numerous British bands, particularly those influenced by blues music including The Rolling Stones, The Animals and The Yardbirds.[29]

The British Invasion arguably spelled the end of instrumental surf music, vocal girl groups and (for a time) the

Garage rock

Garage rock was a raw form of rock music, prevalent in North America in the mid-1960s, and called so because of the perception that it was rehearsed in a suburban family garage.[36][37] Garage rock songs revolved around the traumas of high school life, with songs about "lying girls" being particularly common.[38] The lyrics and delivery were more aggressive than was common at the time, often with growled or shouted vocals that dissolved into incoherent screaming.[36] They ranged from crude one-chord music (like the Seeds) to near-studio musician quality (including the Knickerbockers, the Remains, and the Fifth Estate). There were also regional variations in many parts of the country with flourishing scenes particularly in California and Texas.[38] The Pacific Northwest states of Washington and Oregon had perhaps the most defined regional sound.[39]

The style had been evolving from regional scenes as early as 1958. "Tall Cool One" (1959) by

The British Invasion of 1964–66 greatly influenced garage bands, providing them with a national audience, leading many (often

Blues rock

In America blues rock had been pioneered in the early 1960s by guitarist

Early blues rock bands often emulated jazz, playing long, involved improvisations, which would later be a major element of progressive rock. From about 1967 bands like Cream had begun to move away from purely blues-based music into psychedelia.[48] By the 1970s blues rock had become heavier and more riff-based, exemplified by the work of British bands Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple, and the lines between blues rock and hard rock "were barely visible",[48] as bands began recording rock-style albums.[48] The genre was continued in the 1970s by figures such as George Thorogood,[47] but bands became focused on heavy metal innovation, and blues rock began to slip out of the mainstream.[49]

Folk rock

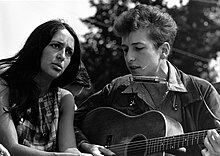

By the 1960s, the scene that had developed out of the American folk music revival had grown to a major movement, using traditional music and new compositions in a traditional style, usually on acoustic instruments.[50] In America the genre was pioneered by figures such as Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger and often identified with progressive or labor politics.[50][51] In the early sixties figures such as Joan Baez and Bob Dylan had come to the fore in this movement as singer-songwriters.[52][53] Dylan had begun to reach a mainstream audience with hits including "Blowin' in the Wind" (1963) and "Masters of War" (1963), which brought "protest songs" to a wider public,[54] but, although beginning to influence each other, rock and folk music had remained largely separate genres, often with mutually exclusive audiences.[55]

The folk rock movement is usually thought to have taken off with

Folk rock reached its peak of commercial popularity in the period 1967-8, before many acts moved off in a variety of directions, including Dylan and the Byrds, who began to develop country rock.[59] However, the hybridization of folk and rock has been seen as having a major influence on the development of rock music, bringing in elements of psychedelia, and helping to develop the ideas of the singer-songwriter, the protest song and concepts of "authenticity".[55][60]

Psychedelic rock

Psychedelic music's

Psychedelic rock particularly took off in California's emerging music scene as groups followed the Byrds from folk to folk rock from 1965.

Psychedelic rock reached its apogee in the last years of the decade. The

Roots rock (late 1960s to early 1970s)

Roots rock is the term now used to describe a move away from what some saw as the excesses of the psychedelic scene, to a more basic form of rock and roll that incorporated its original influences, particularly country and folk music, leading to the creation of country rock and Southern rock.

Country rock

In 1968

Southern rock

The founders of Southern rock are usually thought to be the

New genres (the early 1970s)

Progressive rock

Progressive rock, a term sometimes used interchangeably with

Glam rock

Glam rock was prefigured by the showmanship and gender identity manipulation of American acts such as

Soft and hard rock

From the late 1960s it became common to divide mainstream rock music into soft and hard rock. Soft rock was often derived from folk rock, using acoustic instruments and putting more emphasis on melody and harmonies.[89] Major artists included Carole King, James Taylor and America.[89][90] It reached its commercial peak in the mid- to late- 70s with acts like Billy Joel and the reformed Fleetwood Mac, whose Rumours (1977) was the best-selling album of the decade.[91] In contrast, hard rock was more often derived from blues-rock and was played louder and with more intensity.[92] It often emphasised the electric guitar, both as a rhythm instrument using simple repetitive riffs and as a solo lead instrument, and was more likely to be used with distortion and other effects.[92] Key acts included British Invasion bands like The Who and The Kinks, as well as psychedelic era performers like Cream, Jimi Hendrix and The Jeff Beck Group and American bands including Iron Butterfly, MC5, Blue Cheer and Vanilla Fudge.[92][93] Hard rock-influenced bands that enjoyed international success in the 1970 included Montrose, including the instrumental talent of Ronnie Montrose and vocals of Sammy Hagar and arguably the first all-American hard rock band to challenge the British dominance of the genre, released their first album in 1973,[94] and were followed by bands like Aerosmith.[92]

Early heavy metal

From the late 1960s the term heavy metal began to be used to describe some hard rock played with even more volume and intensity, first as an adjective and by the early 1970s as a noun.

Christian rock

Rock has been criticized by some Christian religious leaders, who have condemned it as immoral, anti-Christian and even demonic.

Punk and its aftermath (mid-1970s to the 1980s)

Punk rock

Punk rock was developed between 1974 and 1976 in the United States and the United Kingdom. Rooted in

New wave

Although punk rock was a significant social and musical phenomenon, it achieved less in the way of record sales,[112] or American radio airplay (as the radio scene continued to be dominated by mainstream formats such as disco and album-oriented rock).[113] Punk rock had attracted devotees from the art and collegiate world and soon bands sporting a more literate, arty approach, such as Talking Heads, and Devo began to infiltrate the punk scene; in some quarters the description "New Wave" began to be used to differentiate these less overtly punk bands.[114] Record executives, who had been mostly mystified by the punk movement, recognized the potential of the more accessible New Wave acts and began aggressively signing and marketing any band that could claim a remote connection to punk or new wave.[115] Many of these bands, such as The Cars, The Runaways and The Go-Go's can be seen as pop bands marketed as new wave;[116] other existing acts, while "skinny tie" bands exemplified by The Knack,[117] or the photogenic Blondie, began as punk acts and moved into more commercial territory.[118]

Post-punk

If hardcore most directly pursued the stripped down aesthetic of punk, and new wave came to represent its commercial wing, post-punk emerged in the later 1970s and early 80s as its more artistic and challenging side. Major influences beside punk bands were The Velvet Underground, The Who, Frank Zappa and Captain Beefheart, and the New York-based no wave scene which placed an emphasis on performance, including bands such as James Chance and the Contortions, DNA and Sonic Youth.[118] Early contributors to the genre included the US bands Pere Ubu, Devo, The Residents and Talking Heads.[118] Although many post-punk bands continued to record and perform, it declined as a movement in the mid-1980s as acts disbanded or moved off to explore other musical other areas, but it has continued to influence the development of rock music and has been seen as a major element in the creation of the alternative rock movement.[119]

Glam and extreme metal

In the late 1970s Eddie Van Halen established himself as a metal guitar virtuoso after his band's self-titled 1978 album.[120] Inspired by Van Halen's success and the new wave of British heavy metal, a metal scene began to develop in Southern California from the late 1970s, based on the clubs of L.A.'s Sunset Strip and including such bands as Quiet Riot, Ratt, Mötley Crüe, and W.A.S.P., who, along with similarly styled acts such as New York's Twisted Sister, incorporated the theatrics (and sometimes makeup) of glam rock acts like Alice Cooper and Kiss.[120] The lyrics of these glam metal bands characteristically emphasized hedonism and wild behavior and musically were distinguished by rapid-fire shred guitar solos, anthemic choruses, and a relatively melodic, pop-oriented approach.[120] By the mid-1980s bands were beginning to emerge from the L.A. scene that pursued a less glam image and a rawer sound, particularly Guns N' Roses, breaking through with the chart-topping Appetite for Destruction (1987), and Jane's Addiction, who emerged with their major label debut Nothing's Shocking, the following year.[121]

In the late 1980s metal fragmented into several subgenres, including

Heartland rock

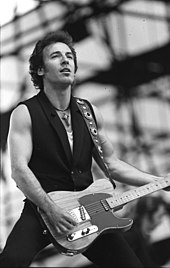

American working-class oriented heartland rock, characterized by a straightforward musical style, and a concern with the lives of ordinary,

Exemplified by the commercial success of singer songwriters

Heartland rock faded away as a recognized genre by the early 1990s, as rock music in general, and blue collar and white working class themes in particular, lost influence with younger audiences, and as heartland's artists turned to more personal works.

Emergence of alternative rock

The term alternative rock was coined in the early 1980s to describe rock artists who did not fit into the mainstream genres of the time. Bands dubbed "alternative" had no unified style, but were all seen as distinct from mainstream music. Alternative bands were linked by their collective debt to punk rock, through hardcore, New Wave or the post-punk movements.

Alternative goes mainstream (the 1990s)

Grunge

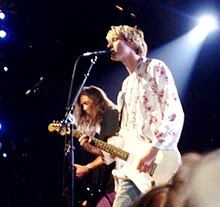

By the early 1990s, rock was dominated by commercialized and highly produced pop, rock, and "hair metal" artists, while MTV had arrived and promoted a focus on image and style. Disaffected by this trend, in the mid-1980s, bands in Washington state (particularly in the Seattle area) formed a new style of rock which sharply contrasted with the mainstream music of the time.[133] The developing genre came to be known as "grunge", a term descriptive of the dirty sound of the music and the unkempt appearance of most musicians, who actively rebelled against the over-groomed images of popular artists.[133] Grunge fused elements of hardcore punk and heavy metal into a single sound, and made heavy use of guitar distortion, fuzz and feedback.[133] The lyrics were typically apathetic and angst-filled, and often concerned themes such as social alienation and entrapment, although it was also known for its dark humor and parodies of commercial rock.[133]

Bands such as

Post-grunge

The term post-grunge was coined for the generation of bands that followed the emergence into the mainstream, and subsequent hiatus, of the Seattle grunge bands. Post-grunge bands emulated their attitudes and music, but with a more radio-friendly commercially oriented sound.[139] Often they worked through the major labels and came to incorporate diverse influences from jangle pop, punk-pop, alternative metal or hard rock.[139] The term post-grunge was meant to be pejorative, suggesting that they were simply musically derivative, or a cynical response to an "authentic" rock movement.[140] From 1994, former Nirvana drummer Dave Grohl's new band, the Foo Fighters, helped popularize the genre and define its parameters.[141]

Some post-grunge bands, like Candlebox, were from Seattle, but the subgenre was marked by a broadening of the geographical base of grunge, with bands like Los Angeles' Audioslave, and Georgia's Collective Soul, who all cemented post-grunge as one of the most commercially viable subgenres of the late 1990s.[131][139] Although male bands predominated, female solo artist Alanis Morissette's 1995 album Jagged Little Pill, labelled as post-grunge, also became a multi-platinum hit.[142] Bands like Creed and Nickelback took post-grunge into the 21st century with considerable commercial success, abandoning most of the angst and anger of the original movement for more conventional anthems, narratives and romantic songs, and were followed in this vein by new acts including Shinedown, Seether and 3 Doors Down.[140]

Pop punk

The origins of 1990s punk pop can be seen in the more song-oriented bands of the 1970s punk movement like

A second wave of punk pop was spearheaded by

Indie rock

In the 1980s the terms indie rock and alternative rock were used interchangeably.

By the end of the 1990s many recognisable subgenres, most with their origins in the late 80s alternative movement, were included under the umbrella of indie.

Alternative metal, rap rock and nu metal

Alternative metal emerged from the hardcore scene of alternative rock in the US in the later 1980s, but gained a wider audience after grunge broke into the mainstream in the early 1990s.

Hip hop had gained attention from rock acts in the early 1980s, including The Clash with "

In 1990, Faith No More broke into the mainstream with their single "Epic', often seen as the first truly successful combination of heavy metal with rap.[163] This paved the way for the success of existing bands like 24-7 Spyz and Living Colour, and new acts including Rage Against the Machine and Red Hot Chili Peppers, who all fused rock and hip hop among other influences.[161][164] Among the first wave of performers to gain mainstream success as rap rock were 311,[165] Bloodhound Gang,[166] and Kid Rock.[167] A more metallic sound – nu metal – was pursued by bands including Limp Bizkit, Korn and Slipknot.[162] Later in the decade this style, which contained a mix of grunge, punk, metal, rap and turntable scratching, spawned a wave of successful bands like Linkin Park, P.O.D. and Staind, who were often classified as rap metal or nu metal, the first of which are the best-selling band of the genre.[168]

In 2001, nu metal reached its peak with albums like Staind's

New millennium (the 2000s)

Emo

Emo emerged from the hardcore scene in 1980s Washington, D.C., initially as "emocore", used as a term to describe bands who favored expressive vocals over the more common abrasive, barking style.

Emo broke into mainstream culture in the early 2000s with the platinum-selling success of Jimmy Eat World's even when they protest the label.

Garage rock/post-punk revival

In the early 2000s, a new group of bands that played a stripped down and back-to-basics version of guitar rock, emerged into the mainstream. They were variously characterised as part of a garage rock, post-punk or new wave revival.[182][183][184][185] There had been attempts to revive garage rock and elements of punk in the 1980s and 1990s and by 2000 several local scenes had grown up in the US.[186] The Detroit rock scene included: The Von Bondies, Electric Six, The Dirtbombs and The Detroit Cobras[187] and that of New York: Radio 4, Yeah Yeah Yeahs and The Rapture.[188]

The commercial breakthrough from these scenes was led by bands including

Metalcore and contemporary heavy metal

Metalcore, originally an American hybrid of thrash metal and hardcore punk, emerged as a commercial force in the mid-2000s.[192] It was rooted in the crossover thrash style developed two decades earlier by bands such as Suicidal Tendencies, Dirty Rotten Imbeciles, and Stormtroopers of Death and remained an underground phenomenon through the 1990s.[193] By 2004, melodic metalcore, influenced by melodic death metal, was sufficiently popular for Killswitch Engage's The End of Heartache and Shadows Fall's The War Within to debut at number 21 and number 20, respectively, on the Billboard album chart.[194][195] Lamb of God, with a related blend of metal styles, hit the number 2 spot on the Billboard charts in 2009 with Wrath.[196] The success of these bands and others such as Trivium, who have released both metalcore and straight-ahead thrash albums, and Mastodon, who played in a progressive/sludge style, inspired claims of a metal revival in the United States, dubbed by some critics the "New Wave of American Heavy Metal".[197][198][199]

Digital electronic rock

In the 2000s, as computer technology became more accessible and

Indie electronic, which had begun in the early 1990s with bands like Stereolab and Disco Inferno, took off in the new millennium as the new digital technology developed, with acts including The Postal Service, and Ratatat from the US, mixing a variety of indie sounds with electronic music, largely produced on small independent labels.[204][205] The Electroclash subgenre began in New York at the end of the 1990s, combining synth pop, techno, punk and performance art. It was pioneered by I-F with their track "Space Invaders Are Smoking Grass" (1998),[206] and pursued by artists including Felix da Housecat[207] and Peaches.[208] It gained international attention at the beginning of the new millennium, but rapidly faded as a recognisable genre.[209] Dance-punk, mixing post-punk sounds with disco and funk, had developed in the 1980s, but it was revived among some bands of the garage rock/post-punk revival in the early years of the new millennium, particularly among New York acts such as Liars, The Rapture and Radio 4, joined by dance-oriented acts who adopted rock sounds such as Out Hud.[210]

See also

Notes

- ^ "The Roots of Rock", Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ "Rock (music)", Encyclopædia Britannica, retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ ISBN 0-495-50530-7, pp. 157–8.

- ^ N. McCormick, "The day Elvis changed the world", Daily Telegraph, June 24, 2004, retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Gilliland 1969, show 5

- ISBN 0-87972-821-3, p. 358.

- ISBN 0-88738-618-0, p. 13.

- AllMusic. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, shows 6–7, 12.

- ISBN 0-415-93835-X, pp. 327–8.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 13.

- ^ a b Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, pp. 1306–7

- ISBN 0-87972-369-6, p. 73.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, shows 15–17.

- ^ Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, pp. 1323–4

- ^ Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, pp. 1319–20

- ^ ISBN 0-521-55660-0, p. 116.

- ^ a b Gilliland 1969, show 20.

- ISBN 0-495-50530-7, p. 99.

- ISBN 0-415-05306-4, p. 341.

- ISBN 0-905273-17-6, p. 106.

- ^ Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, pp. 1311–2

- ISBN 0-87650-174-9, p. 2.

- ISBN 0-87650-174-9, p. 75.

- ^ a b c d e Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, pp. 1313–4

- ^ a b c Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, pp. 71–2

- ^ a b Gilliland 1969, show 37.

- ISBN 0-85323-727-1, pp. 157–66.

- ^ a b "British Invasion", Allmusic, retrieved January 29, 2010.

- ^ "British Invasion" Encyclopædia Britannica, retrieved January 29, 2010.

- ISBN 0-7137-1521-9, p. 66.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 28.

- ISBN 0-521-55660-0, p. 117.

- ISBN 0-415-93835-X, p. 132.

- ISBN 0-415-34770-X, p. 35.

- ^ ISBN 0-415-34770-X, p. 140.

- ISBN 0-7864-2564-4, pp. 74–6.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, pp. 1320–1

- ISBN 0-7486-1933-X, p. 213.

- ISBN 0-7890-0151-9, p. 213.

- ISBN 1-55652-572-9, p. 19.

- ISBN 0-520-25310-8, p. 116.

- ISBN 0-415-93835-X, p. 873.

- ^ W. Osgerby, "'Chewing out a rhythm on my bubble gum': the teenage astheic and genealogies of American punk," p. in Sabin 1999.

- ISBN 0-7486-1910-0, p. 134.

- ISBN 0-7935-4042-9, p. 25.

- ^ ISBN 0-87930-736-6, pp. 700–2.

- ^ a b c "Blues rock", Allmusic, retrieved September 29, 2006.

- ISBN 0-7935-4042-9, p. 113.

- ^ ISBN 0-7546-5756-6, p. 95.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 18.

- ISBN 0-7546-5756-6, p. 72.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 19.

- ISBN 0-313-32689-4, p. 37.

- ^ a b c d e f Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, pp. 1308–9

- ^ a b Gilliland 1969, show 33.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 32.

- ^ a b Gilliland 1969, show 36.

- ISBN 0-520-21800-0, p. 201.

- ISBN 0-521-55660-0, p. 121.

- ^ ISBN 0-252-06915-3, pp. 59–60.

- ^ a b c d Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, pp. 1322–3

- ^ Gilliland 1969, shows 41–42.

- ^ a b Gilliland 1969, show 47.

- ISBN 0-7890-0151-9, p. 223.

- ISBN 0-313-32689-4, p. 24.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 55.

- ISBN 0-415-77353-9, p. 83.

- ^ ISBN 1-85828-534-8, p. 392.

- ^ Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, pp. 61, 265

- ISBN 0-470-12777-5, pp. 87–90.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, p. 1327

- ISBN 1-84353-105-4, p. 730.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 9.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 11.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 44.

- ISBN 0-8108-5295-0, pp. 227–8.

- ^ a b c d Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, pp. 1332–3

- ^ a b Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, pp. 1330–1

- ISBN 0-634-02861-8, p. 191.

- ISBN 0-19-509887-0, p. 64.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 43.

- ISBN 0-8108-5295-0, pp. 249–50.

- ISBN 0-472-06868-7, p. 34.

- ^ ISBN 0-415-34770-X, pp. 124–5.

- ISBN 0-7546-4057-4, pp. 57, 63, 87, 141.

- ^ "Glam rock", Allmusic, retrieved June 26, 2009.

- ISBN 0-7546-4057-4, p. 80.

- ^ ISBN 0-87972-369-6, p. 236.

- ^ S. T. Erlewine, "America: biography", Allmusic , August 11, 2012.

- ISBN 1-84353-105-4, p. 378.

- ^ a b c d "Hard Rock", Allmusic, retrieved November 11, 2009.

- ISBN 0-8195-6260-2, pp. 9–10.

- ^ E. Rivadavia, "Montrose", Allmusic, retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ISBN 0-8195-6260-2, p. 7.

- ISBN 0-8195-6260-2, p. 9.

- ^ ISBN 0-8195-6260-2, p. 10.

- ISBN 0-8195-6260-2, p. 3.

- ISBN 1-55022-421-2, pp. 30–1.

- ISBN 0-8131-9086-X, p. 30.

- ISBN 0-8131-9086-X, pp. 43–4.

- ISBN 0-8264-5937-4, p. 811.

- ISBN 1-55022-421-2, pp. 66–7, 159–161.

- ISBN 0-8135-1607-2, p. 134.

- ISBN 1-55022-421-2, pp. 206–7.

- ^ a b Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, p. 1336

- ISBN 0-415-94365-5, pp. 235–56.

- ^ Sabin 1999, p. 206.

- ISBN 1-4426-0992-3, p. xi.

- ^ "Punk Revival", Allmusic, retrieved December 12, 2009.

- ^ Hardcore punk, Allmusic, retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ISBN 0-520-25310-8, p. 157.

- ISBN 0-415-96589-6, p. 358.

- ISBN 0-495-50530-7, pp. 273–4.

- ISBN 0-415-34770-X, pp. 185–6.

- ISBN 1-84353-105-4, pp. 174, 430.

- ISBN 0-9797714-0-4, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, pp. 1337–8

- ^ D. Hesmondhaigh, "Indie: the institutional political and aesthetics of a popular music genre" in Cultural Studies, 13 (2002), p. 46.

- ^ ISBN 0-380-81127-8, pp. 51–7.

- ISBN 0-86547-966-6, p. 241.

- ^ Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, p. 1332

- ISBN 0-8195-6260-2, pp. 11–14.

- ISBN 0-7864-1585-1, pp. 9, 53.

- ISBN 0-275-98938-0, p. 51.

- ISBN 0-7486-1910-0, p. 138.

- ^ a b c d "Heartland rock", Allmusic, retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ^ J. Parles, "Heartland rock: Bruce's Children", New York Times, August 30, 1987, retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ISBN 0520215877, p. 137.

- ^ S. Peake, "Heartland rock" Archived 2011-05-12 at the Wayback Machine, About.com, retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, pp. 1344–7

- ISBN 0-631-21710-X, pp. 94–105.

- ^ a b c d "Grunge", Allmusic, retrieved March 8, 2003.

- ^ E. Olsen, "10 years later, Cobain continues to live on through his music", MSNBC.com, retrieved September 4, 2009.

- ISBN 1-903364-96-5, p. 136.

- ^ R. Marin, "Grunge: A Success Story", The New York Times November 15, 1992.

- ISBN 0-316-78753-1, pp. 452–53.

- ^ "Post-grunge", Allmusic, retrieved September 28, 2007.

- ^ a b c "Post-grunge", Allmusic, retrieved December 31, 2009.

- ^ a b T. Grierson, "Post-Grunge: A History of Post-Grunge Rock" Archived 2011-05-14 at the Wayback Machine, About.com, retrieved January 1, 2010.

- ^ Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, p. 423

- ^ Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, p. 761

- ^ a b c d W. Lamb, "Punk Pop" Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, About.com Guide, retrieved January 1, 2010.

- ^ "Pop-punk", Allmusic, retrieved January 1, 2010.

- ^ S. T. Erlewine, "Weezer", Allmusic, retrieved January 1, 2010.

- ^ Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, pp. 484–5, 816

- ^ a b c d "Indie rock", Allmusic, retrieved December 29, 2009.

- ISBN 0-7546-3862-6, p. 2.

- ISBN 0-8264-8217-1, pp. 154–5.

- ^ "Post rock", Allmusic, retrieved December 31, 2009.

- ^ "Math rock", Allmusic, retrieved December 31, 2009.

- ^ "Sadcore", Allmusic, retrieved December 31, 2009.

- ^ "Chamber pop", Allmusic, retrieved December 31, 2009.

- ^ a b "Alternative Metal", Allmusic, retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ R. Christgau, "Review of Autoamerican", Allmusic, retrieved December 31, 2008.

- ^ D. A. Guarisco, "Review of 'The Magnificent Seven'", Allmusic, retrieved December 31, 2008.

- ^ K. Sanneh, "Rappers Who Definitely Know How to Rock", The New York Times, December 3, 2000, retrieved December 31, 2008.

- ^ S. Erlewine, Licensed to Ill, Allmusic, retrieved December 31, 2008.

- ISBN 0-252-07201-4, p. 108.

- ^ W. E. Ketchum III, "Mayor Esham? What?", Metro Times, October 15, 2008, retrieved October 16, 2008.

- ^ a b A. Henderson, "Genre essay: Rap-Metal", Allmusic, retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ a b "Rap-metal", Allmusic, retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, pp. 388–9

- ^ a b T. Grierson, "What Is Rap-Rock: A Brief History of Rap-Rock" Archived December 29, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, About.com, retrieved December 31, 2008.

- ^ C. Nixon, "Anything goes" The San Diego Union-Tribune August 16, 2007, retrieved December 31, 2008.

- ^ T. Potterf, "Turners blurs line between sports bar, dance club", The Seattle Times, October 1, 2003, retrieved December 31, 2008.

- ^ "Long Live Rock n' Rap: Rock isn't dead, it's just moving to a hip-hop beat. So are its mostly white fans, who face questions about racial identity as old as Elvis", Newsweek, July 19, 1999, retrieved December 31, 2008.

- ISBN 0-7119-9209-6, p. 10.

- ^ B. Reeceman, "Sustaining the success", Billboard, June 23, 2001, 113 (25), p. 25.

- ^ a b J. D'Angelo, "Will Korn, Papa Roach and Limp Bizkit evolve or die: a look at the Nu Metal meltdown" Archived 2010-12-21 at the Wayback Machine, MTV, retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "RIAA Gold and Platinum Data". RIAA.

- ^ "Here to Stay - Korn". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media.

- ^ "The TRL Archive - Recap: May 2002". ATRL. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2015. Retrieved on September 15, 2015.

- ^ "Private Tutor". Infoplease.com.

- ^ a b c d e f "Emo", Allmusic, retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ^ M. Jayasuriya, "In Circles: Sunny Day Real Estate Reconsidered", Pop Matters, September 15, 2009, retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ^ a b J. DeRogatis, "True Confessional?". October 3, 2003, retrieved April 10, 2010.

- ^ H. A. S. Popkin, "What exactly is 'emo,' anyway?", MSNBC.com, March 26, 2006, retrieved April 10, 2010.

- ^ a b F. McAlpine, Paramore "Misery Business", June 14, 2007, BBC.co.uk, retrieved April 2, 2009.

- ^ "My Chemical Romance"[dead link], Rolling Stone retrieved December 11, 2010.

- ^ "Panic! At The Disco declare emo 'Bullshit!' The band reject 'weak' stereotype", NME, December 18, 2006, retrieved August 10, 2008.

- ^ H. Phares, "Franz Ferdinand: Franz Ferdinand (Australia Bonus CD)", Allmusic, retrieved January 6, 2010.

- ISBN 0-634-05548-8, p. 373.

- ^ "New Wave/Post-Punk Revival" Allmusic, retrieved January 6, 2010.

- ISBN 0-7119-9601-6, p. 86.

- ISBN 1-84353-229-8, p. 42.

- ISBN 1-84353-105-4, p. 1144.

- ISBN 1-74104-889-3, p. 33.

- ISBN 1-84353-105-4, pp. 498–9, 1040–1, 1024–6 and 1162-4.

- ISBN 0-19-537371-5, p. 240.

- ISBN 0-335-20072-9, p. 90.

- ISBN 0-380-81127-8, p. 372.

- ISBN 0-380-81127-8, p. 184.

- ^ "Killswitch Engage", Roadrunner Records, retrieved March 7, 2003.

- ^ Fall "Shadows Fall"[permanent dead link], Atlantic Records, retrieved March 17, 2007.

- idiomag, retrieved November 3, 2008.

- ISBN 0-9582684-0-1.

- ^ J. Edward, "The Ghosts of Glam Metal Past" Archived 2011-01-08 at the Wayback Machine, Lamentations of the Flame Princess, retrieved April 27, 2008.

- ^ A. Begrand, "Blood and Thunder: Regeneration", Popmatters, retrieved May 14, 2008.

- ^ ISBN 0-7546-5548-2, pp. 80–1.

- ISBN 0-415-34770-X, pp. 145–8.

- ISBN 0-7546-5548-2, p. 115.

- ^ T. Jurek, "Nine Inch Nails – Year Zero", Allmusic retrieved March 13, 2008.

- ^ "Indie electronic", Allmusic retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ^ S. Leckart, "Have laptop will travel", MSNBC retrieved September 25, 2006.

- ^ D. Lynskey, "Out with the old, in with the older", Guardian.co.uk, March 22, 2002, retrieved January 16, 2010.

- ^ M. Goldstein, "This cat is housebroken, Boston Globe, retrieved May 16, 2008.

- ^ J. Walker, "Popmatters concert review: ELECTROCLASH 2002 Artists: Peaches, Chicks on Speed, W.I.T., and Tracy and the Plastics", Popmatters, October 5, 2002, retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ISBN 1-84744-293-5, p. 78.

- ^ M. Wood, "Review: Out Hud: S.T.R.E.E.T. D.A.D.", New Music, 107, November 2002, p. 70.

Sources

- Bogdanov, V.; Woodstra, C.; Erlewine, S. T. (2002). All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (3rd ed.). Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930-653-X.

- Gilliland, John (1969). "Hail, Hail, Rock 'n' Roll: The rock revolution gets underway" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries.

- Sabin, R. (1999). Punk Rock: So What?: the Cultural Legacy of Punk. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-17029-X.