Battle of Seven Pines

| Battle of Seven Pines | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Alfred R. Waud) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Edwin V. Sumner |

D. H. Hill | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 34,000[1] | 39,000[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 5,431 total | 6,134 total | ||||||

The Battle of Seven Pines, also known as the Battle of Fair Oaks or Fair Oaks Station, took place on May 31 and June 1, 1862, in

The

The Confederate assaults, although poorly coordinated, succeeded in driving back the

Gen. Johnston was seriously wounded during the action, and command of the Confederate army devolved temporarily to Maj. Gen. G.W. Smith.

On June 1, the Confederates renewed their assaults against the Federals, who had brought up more reinforcements, but made little headway. Both sides claimed victory.[3]

Although the battle was tactically inconclusive, it was the largest battle in the

Background

Johnston withdrew his 75,000-man army from the Virginia Peninsula as McClellan's army pursued him and approached the Confederate capital of Richmond. Johnston's defensive line began at the

The Army of the Potomac pushed slowly up the Pamunkey, establishing supply bases at Eltham's Landing, Cumberland Landing, and White House Landing. White House, the plantation of

Opposing forces

Union

| Key Union Commanders |

|---|

|

The Union

Confederate

| Key Confederate Commanders |

|---|

|

Johnston had 60,000 men in his Army of Northern Virginia protecting the defensive works of Richmond in eight divisions commanded by Maj. Gen James Longstreet, Maj. Gen

Johnston's plan

Johnston, who had retreated up the Peninsula to the outskirts of Richmond, knew that he could not survive a massive siege and decided to attack McClellan. His original plan was to attack the Union right flank, north of the Chickahominy River, before McDowell's corps, marching south from Fredericksburg, could arrive. However, on May 27, the same day the Battle of Hanover Court House was fought northeast of Richmond, Johnston learned that McDowell's corps had been diverted to the Shenandoah Valley and would not be reinforcing the Army of the Potomac. He decided against attacking across his own natural defense line, the Chickahominy, and planned to capitalize on the Union army's straddle of the river by attacking the two corps south of the river, leaving them isolated from the other three corps north of the river.[9]

If executed correctly, Johnston would engage three quarters of his army (22 of its 29 infantry brigades, about 51,000 men) against the 33,000 men in the III and IV Corps. The Confederate attack plan was complex, calling for the divisions of A. P. Hill and Magruder to engage lightly and distract the Union forces north of the river, while Longstreet, commanding the main attack south of the river, was to converge on Keyes from three directions: six brigades under Longstreet's immediate command and four brigades under D. H. Hill were to advance on separate roads at a crossroads known as Seven Pines (because of seven large pine trees clustered at that location); three brigades under Huger were assigned to support Hill's right; Whiting's division was to follow Longstreet's column as a reserve. The plan had an excellent potential for initial success because the division of the IV Corps farthest forward, manning the earthworks a mile west of Seven Pines, was that of Brig. Gen. Silas Casey, 6000 men who were the least experienced and equipped in Keyes's corps. If Keyes could be defeated, the III Corps, to the east, could be pinned against the Chickahominy and overwhelmed.[10]

The complex plan was mismanaged from the start. Johnston chose to issue his orders to Longstreet orally in a long and rambling meeting on May 30. The other generals received written orders that were vague and contradictory. He also failed to notify all of the division commanders that Longstreet was in tactical command south of the river. (This missing detail was a serious oversight because both Huger and Smith technically outranked Longstreet.) On Longstreet's part, he either misunderstood his orders or chose to modify them without informing Johnston. Rather than taking his assigned avenue of advance on the Nine Mile Road, his column joined Hill's on the Williamsburg Road, which not only delayed the advance, but limited the attack to a narrow front with only a fraction of its total force. Exacerbating the problems on both sides was a severe thunderstorm on the night of May 30, which flooded the river, destroyed most of the Union bridges, and turned the roads into morasses of mud.[11]

Battle

The attack got off to a bad start on May 31 when Longstreet marched down the Charles City Road and turned onto the Williamsburg Road instead of the Nine Mile Road. Huger's orders had not specified a time that the attack was scheduled to start and he was not awakened until he heard a division marching nearby. Johnston and his second-in-command, Smith, unaware of Longstreet's location or Huger's delay, waited at their headquarters for word of the start of the battle. Five hours after the scheduled start, at 1 p.m., D.H. Hill became impatient and sent his brigades forward against Casey's division.[12]

Hill's division, some 10,000 men strong, came charging out of the woods. The 100th and 81st New York regiments had been placed up front as heavy skirmish lines, and Hill's assault rolled completely over them. Casey's line, manned by inexperienced troops, buckled with some men retreating, but fought fiercely for possession of their earthworks, resulting in heavy casualties on both sides. The Confederates only engaged four brigades of the thirteen on their right flank that day, so they did not hit with the power that they could have concentrated on this weak point in the Union line. Casey sent a frantic request for help, but Keyes was slow in responding. Eventually the mass of Confederates broke through, seized a Union redoubt, and Casey's men retreated to the second line of defensive works at Seven Pines. During this period, both of the high commanders were unaware of the severity of the battle. As late as 2:30 p.m., Heintzelman reported to McClellan, still sick in bed, that he had received no word from Keyes. Johnston was only 2+1⁄2 miles from the front, but an

The Army of the Potomac was accompanied by the Union Army Balloon Corps commanded by Prof. Thaddeus S. C. Lowe, who had established two balloon camps on the north side of the river, one at Gaines's Farm and one at Mechanicsville. Lowe reported on May 29 the buildup of Confederate forces to the left of New Bridge or in front of the Fair Oaks train station.[14] With constant rain on May 30 and heavy winds the morning of May 31, the aerostats Washington and Intrepid did not launch until noon. Lowe observed Confederate troops moving in battle formation and this information was relayed verbally to McClellan's headquarters by 2 p.m.[14] Lowe continued to send reports from the Intrepid via telegraph the remainder of May 31. On June 1, Lowe reported that the Confederate barracks to the left of Richmond as being free from smoke.[15] McClellan did not follow up on this information with a counterattack by his corps north of the Chickahominy River.[16]

Around 1:00 p.m., Hill, now strengthened by the arrival of Richard Anderson's brigade, hit the secondary Union line near Seven Pines, which was manned by the remnants of Casey's division, the IV Corps division of Brig. Gen. Darius N. Couch, and Brig. Gen. Philip Kearny's division from Heintzelman's III Corps. Hill organized a flanking maneuver, sending four regiments under Col. Micah Jenkins from Longstreet's command to attack Keyes's right flank. The attack collapsed the Federal line back to the Williamsburg Road, a mile and a half beyond Seven Pines. Meanwhile, another of Longstreet's brigades under Col. James L. Kemper, arrived on the field and charged the Union lines, but artillery fire forced them to retreat. The fighting in that part of the line died out by 7:30 p.m. During the evening, Longstreet himself arrived on the field along with the remaining four brigades of his division, as well as the three brigades of Huger's division. On the Union side, Brig. Gen Israel Richardson's division of the II Corps arrived on the field, along with Joe Hooker's division of the III Corps (minus one brigade and the division artillery which were left guarding the bridges over White Oak Swamp).[17]

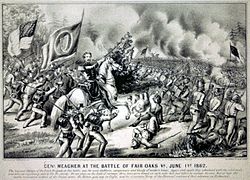

Just before Hill's attack began, Johnston received a note at approximately 4:00 pm from Longstreet requesting that he join the battle, the first news he had heard of the fighting. Johnston went forward on the Nine Mile Road, with a five brigade division led by Brig. Gen. William Chase Whiting. Hours earlier that day, Whiting had been elevated into command of Maj. Gen. Gustavus Smith's division. As the lead regiment of the division, led by Col. Dorsey Pender, 6th NC, reached the railroad crossing artillery guns opened on Pender's advance. This opened the segment of the Battle of Seven Pines to be known as the Battle of Fair Oaks Station. The guns were a part of Brig. Gen John Abercrombie's brigade of Couch's division and they began to put up a stiff resistance. Whiting advanced his former brigade, commanded by Col.

The most historically significant incident of the day occurred around dusk, when Johnston was struck in the right shoulder by a bullet, immediately followed by a shell fragment hitting him in the chest. He fell unconscious from his horse with a broken right shoulder blade and two broken ribs and was evacuated to Richmond. G.W. Smith assumed temporary command of the army. Smith, plagued with ill health, was indecisive about the next steps for the battle and made a bad impression on Confederate President Jefferson Davis and General Robert E. Lee, Davis's military adviser. After the end of fighting the following day, Davis replaced Smith with Lee as commander of the Army of Northern Virginia.[19]

During the night of May 31 – June 1, scouts in Israel Richardson's division reported two Confederate regiments camped only about 100 yards away. Richardson declined to make a risky night attack, but had his troops form a line of battle just in case. By daybreak however, the enemy regiments had withdrawn from their exposed location. At 6:30 am, the Confederates resumed their attacks. Two of Huger's three brigades, commanded by Brig. Gens

Aftermath

Both sides claimed victory with roughly equal casualties, but neither side's accomplishment was impressive. George B. McClellan's advance on Richmond was halted and the Army of Northern Virginia fell back into the Richmond defensive works. Union casualties were 5,031 (790 killed, 3,594 wounded, 647 captured or missing) and Confederate 6,134 (980 killed, 4,749 wounded, 405 captured or missing), making it the second largest and bloodiest battle of the war to date after Shiloh eight weeks earlier.[2] The battle was frequently remembered by the Union soldiers as the Battle of Fair Oaks Station because that is where they did their best fighting, whereas the Confederates, for the same reason, called it Seven Pines. Historian Stephen W. Sears remarked that its current common name, Seven Pines, is the most appropriate because it was at the crossroads of Seven Pines that the heaviest fighting and highest casualties occurred.[24] A contemporary map drawn by private Julius Honore Bayol of the 5th Alabama Infantry Regiment,[25] refers simply to the engagement as having occurred at the "Battlefield of 31st of May and 1st June, 62."[26]

Despite claiming victory, McClellan was shaken by the experience. He wrote to his wife, "I am tired of the sickening sight of the battlefield, with its mangled corpses & poor suffering wounded! Victory has no charms for me when purchased at such cost."

After taking command, Robert E. Lee embarked on a reorganization of the Confederate army, breaking up and reassigning some brigades, nominating replacements for dead and wounded officers, and removing two brigadiers,

In MacKinlay Kantor's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Andersonville (1955), Henry Wirz, one of the main characters, reflects often upon the circumstances of the battle, in which he purportedly received a severe arm injury ("God damn the Yankee who did this to me").

See also

- Troop engagements of the American Civil War, 1862

- Peninsula Campaign and Siege of Yorktown (1862)

- List of costliest American Civil War land battles

Notes

- ^ a b "CWSAC Report Update" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved September 24, 2011.

- ^ a b c Sears, p.147.

- ^ "National Park Service". Archived from the original on May 29, 2015. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- ^ Miller, p. 25.

- ^ Salmon, p. 88; Eicher, pp. 273–74; Sears, pp. 95–97.

- ^ Salmon, p. 90; Sears, pp. 104–06.

- ^ Eicher, pp. 276–77.

- ^ Eicher, p. 276.

- ^ Salmon, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Sears, pp. 118–20; Miller, p. 21; Salmon, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Sears, p. 120; Miller, pp. 21–22; Downs, pp. 675–76; Salmon, p. 92.

- ^ Miller, p. 22; Eicher, p. 276; Sears, pp. 121–23.

- ^ Eicher, p. 277; Salmon, p. 93.

- ^ a b Lowe, p. 133.

- ^ Lowe, pp. 135–137.

- ^ Sears, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Miller, p. 23; Eicher, pp. 277–78; Salmon, p. 94.

- ^ Eicher, p. 278; Sears, pp. 136–38, 143; Miller, p. 23; Salmon, p. 94.

- ^ Sears, pp. 145; Miller, p. 24; Salmon, p. 94.

- ^ Sears, pp. 142–45.

- ^ "Battles and Leaders of the Civil War Volume II "North to Antietam"p.232

- ^ The Photographic History of The Civil War Volume 01 Page 304

- ^ "Battles and Leaders of the Civil War Volume II "North to Antietam"p.262

- ^ Sears, p. 149.

- ^ WorldCat, Battlefield of 31st May and 1st June, 1862. Author: Julius Honore Bayol. OCLC Number:122568405

- ^ Alabama Department of Archives and History, Battle of Seven Pines. Main Author: Bayol, Julius H., Title/Description: Battlefield of the 31st May and 1st June, 1862. Battle of Seven Pines, 5th Ala. Infantry Regt. Publication Info: unpublished, hand drawn. http://alabamamaps.ua.edu/historicalmaps/civilwar/sevenpines.html Archived December 11, 2019, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Eicher, p. 279.

- ^ Miller, pp. 25–60.

References

- Downs, Alan C. "Fair Oaks/Seven Pines." In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

- ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Esposito, Vincent J. West Point Atlas of American Wars. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1959. OCLC 5890637. The collection of maps (without explanatory text) is available online at the West Point website.

- ISBN 978-0-7734-6522-0.

- Miller, William J. The Battles for Richmond, 1862. National Park Service Civil War Series. Fort Washington, PA: U.S. National Park Service and Eastern National, 1996. ISBN 0-915992-93-0.

- Salmon, John S. The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001. ISBN 0-8117-2868-4.

- ISBN 0-89919-790-6.

- National Park Service battle description

- Virginia War Museum battle description

- CWSAC Report Update

Memoirs and primary sources

- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Recordsof the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

Further reading

- Burton, Brian K. The Peninsula & Seven Days: A Battlefield Guide. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8032-6246-1.