Congress Heights

Congress Heights | |

|---|---|

Neighborhood | |

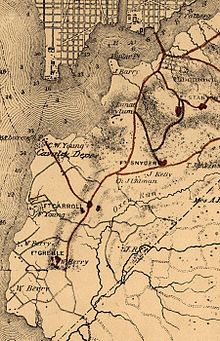

Map of Washington, D.C., with the Congress Heights neighborhood highlighted in red | |

| Coordinates: 38°50′25.5948″N 077°00′00″W / 38.840443000°N 77.00000°W | |

| Country | United States |

| Territory | Washington, D.C. |

| Ward | Ward 8 |

| Constructed | 1890 |

| Government | |

| • Councilmember | Trayon White |

Congress Heights is a residential neighborhood in

History of the neighborhood

Pre-development years

Prior to its development, the area known as Congress Heights was forest and farmland. The bay between Poplar Point and Giesborough Point was open water, and would not be filled in and reclaimed for use until the 1880s. The area was served primarily by the Navy Yard Bridge (now known as the

Additional construction in the area occurred during the American Civil War (1861 to 1865). The United States Department of War constructed the George Washington Young cavalry magazine on 90 acres (360,000 m2) of land on Giesborough Point.[5] Two forts, Fort Carroll (near the present intersection of South Capitol Street and Martin Luther King, Jr. Avenue) and Fort Greble (near the intersection of Martin Luther King, Jr. Avenue and Blue Plains Drive SW), were constructed on the bluffs that began just west and adjacent to Asylum Road. After the war, the 375-acre (1,520,000 m2) Barry Farm housing development for freed slaves opened in 1867 on the north side of the St. Elizabeths campus and was rapidly occupied.[6] Asylum Avenue was named Nichols Avenue in 1879 in honor of St. Elizabeths Hospital superintendent Charles Henry Nichols.[7]

Asylum Avenue/Nichols Avenue was the only major southward road through the area until the development of Congress Heights itself. The only other major street was a military road (now known as Alabama Avenue SE) which ran in an east-northeasterly direction toward other Civil War forts.

Founding of Congress Heights

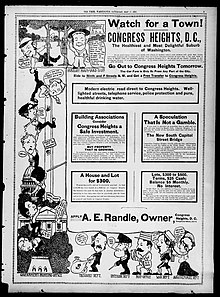

Congress Heights itself was founded in 1890. Colonel Arthur E. Randle,[a][9] a successful newspaper publisher, decided to found a settlement east of the river which he called Congress Heights.[10] The Pennsylvania Avenue Bridge (which was replaced by the John Philip Sousa Bridge) began construction in November 1887,[11] and by June 1890 was nearing completion.[12] Randle understood that this new bridge would bring rapid development east of the Anacostia River, and he intended to take advantage of it.

The development was immediately successful.[13] To ensure that his investment continued to pay off, Randle invested heavily in the Belt Railway, a local streetcar company founded in March 1875.[13][b][14][15][16] On March 2, 1895, Randle founded the Capital Railway Company to construct streetcar lines over the Navy Yard Bridge and down Nichols Avenue to Congress Heights.[13][14] The Belt Railway was purchased on June 24, 1898, by the Anacostia and Potomac River Railway Company.[c][14][15][16] This made Randle a majority owner of the Anacostia and Potomac River Railway. Randle sold his interest in the Capital Railway in 1899,[17] and used this fortune to buy a large section of land known as "East Washington Highlands" at the foot of the Pennsylvania Avenue Bridge.[18] This became the development of Randle Highlands, and the success of that development allowed him to create "North Randle Highlands" (now the neighborhoods of Dupont Park, Penn Branch, and the lower portion of Greenway) In October 1906, The Washington Post called Randle's developments "among the largest real estate enterprises ever successfully carried through in the District."[19]

The rapid development of Congress Heights and the areas adjacent to the streetcar line on Nichols Avenue led the government of the District of Columbia to extend South Capitol Street into the area east of the Anacostia River. The topography of the area largely dictated the route. Beginning near St. Elizabeths Hospital, a line of bluffs extended roughly southward until it reached what is now Chesapeake Street SW. (Fort Greble sat atop the southernmost of these cliffs.) To the west of these bluffs were broad, flat lowlands which provided pleasant views of the Potomac River and the city of Alexandria, Virginia. In 1893, the city surveyed South Capitol along the western side of these bluffs, laying out a broad, grand avenue.[5] Once the bluffs ended, the route followed existing local roads and curved eastward to connect with Livingston Road (now the Indian Head Highway) at the District-Maryland line. But because of the lack of development south of Congress Heights, South Capitol Street was only constructed to its intersection with Nichols Avenue.[20]

20th-century development

From the 1930s until the 1950s, Congress Heights was an almost all-white working-class neighborhood. Many of these white working-class people were rural Southerners and Appalachians who had migrated from Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. Many of them worked at the Navy Yard or at nearby Bolling Air Force Base.[21]

Congress Heights was the location of the last working farm within the District of Columbia. George Lindner had been growing vegetables on his farm for over 50 years and it had been in the family since the Civil War. The farm shut down in 1939.[22]

Prior to

Congress Heights experienced great urban neglect after World War II. However, in the 21st century, Congress Heights has received a great deal of attention from the city and urban developers. Nineteen development projects worth a total of $455 million are underway or completed in Congress Heights as of November 2006. Among these are a redevelopment of St. Elizabeths West Campus for federal use; a request for proposals from the

The neighborhood is served by the

Destination Congress Heights (Congress Heights Main Street) was chartered by the National Trust for Historic Preservation Main Street program in January 2016. Destination Congress Heights is a program created by Congress Heights Community Training & Development Corporation, a nonprofit

References

- Notes

- Governor of the state of Mississippi, in 1902.

- ^ The Capitol, North O Street, and South Washington Railway Company was chartered by Congress on March 3, 1875. By act of Congress enacted on February 18, 1893, it changed its name to the Belt Railway.

- ^ The Anacostia and Potomac River Railway Company was founded on May 19, 1872, but not chartered by Congress until February 18, 1875.

- Citations

- ^ "Subchapter IV. Public Space Names and Commemorative Works". D.C. Law Library. Retrieved 2021-07-22.

Designation of Malcolm X Avenue: Section 2 of D.C. Law 9-225 provided that the Council of the District of Columbia designates the portion of Portland Street, S.E., between 9th Street, S.E. and South Capitol Street, S.E., as Malcolm X Avenue.

- ^ Croggon, James (July 7, 1907). "Old 'Burnt Bridge'". Washington Evening Star.

- ^ Burr 1920, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Benedetto, Du Vall & Donovan 2001, p. 201.

- ^ a b Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce 1894, p. 3.

- ^ Davidson & Malloy 2009, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Evelyn, Dickson & Ackerman 2008, p. 286.

- ^ Tom (2012-04-29). "Congress Heights: The Healthiest and Most Delightful Suburb of Washington". Ghosts of DC. Retrieved 2019-02-25.

- ^ "Col. Randle Kills Self in California". The Washington Post. July 5, 1929.

- ^ General Services Administration 2012, p. 4—27.

- ^ "It Was East End Day". The Washington Post. August 26, 1890.

- ^ "A Bridge Celebration". The Washington Post. June 3, 1890.

- ^ a b c Proctor, Black & Williams 1930, p. 732.

- ^ a b c "Electric Railways". Municipal Journal & Public Works. February 26, 1908. p. 252.

- ^ a b Fennell 1948, p. 15.

- ^ a b Tindall 1918, pp. 39–41.

- ^ Tindall 1918, pp. 41.

- ^ Smith 2010, pp. 402–403.

- ^ "New Suburb Opens". The Washington Post. October 25, 1906.

- ^ "Plans for Street Projects Told By Whitehurst". The Washington Post. September 24, 1940.

- ^ "A Brief History of White People in Southeast". Washington City Paper. Retrieved 2019-05-03.

- ^ Tom (2013-08-12). "Last Farm in the District is Doomed". Ghosts of DC. Retrieved 2019-02-25.

- ^ Washington DC Economic Partnership 2014, p. 15.

Bibliography

- Benedetto, Robert; Du Vall, Kathleen; Donovan, Jane (2001). Historical Dictionary of Washington, D.C. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810840942.

- Burr, Charles R. (1920). "A Brief History of Anacostia, Its Name, Origin, and Progress". Records of the Columbia Historical Society. The Society.

- Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce (1894). "Survey of a Bridge Across the Eastern Branch of the Potomac. Senate Report No. 1210. 53rd Cong., 2d sess.". The Reports of the Committees of the House of Representatives for the Second Session of the Fifty-Third Congress, 1893-94. Vol. 4. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

- Davidson, Nestor M.; Malloy, Robin Paul (2009). Affordable Housing and Public-Private Partnerships. Burlington, Vt.: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754694380.

- Evelyn, Douglas E.; Dickson, Paul; Ackerman, S.J. (2008). On This Spot: Pinpointing the Past in Washington, D.C. Sterling, Va.: Capital Books. ISBN 9781933102702.

- Fennell, Margaret L. (1948). Corporations Chartered By Special Act of Congress. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress.

- General Services Administration (2012). Department of Homeland Security Headquarters Consolidation at St. Elizabeths Master Plan Amendment, East Campus North Parcel: Environmental Impact Statement. Washington, D.C.: General Services Administration.

- Proctor, John Clagett; Black, Frank P.; Williams, E. Melvin (1930). Washington, Past and Present: A History. New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Co.

- Smith, Kathryn Schneider (2010). Washington At Home: An Illustrated History of Neighborhoods in the Nation's Capital. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801893537.

- Tindall, William (1918). "Beginnings of Street Railways in the National Capital". Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C.: 24–86.

- Washington DC Economic Partnership (2014). DC Neighborhood Profiles 2014 (via Wayback Machine) (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: Washington DC Economic Partnership. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-17.

- Washington DC Economic Partnership. Congress Heights/Saint Elizabeths - WDCEP (Report). Washington, D.C.: Washington DC Economic Partnership.