Henry Sidgwick

Henry Sidgwick | |

|---|---|

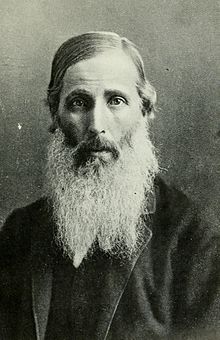

Sidgwick photographed by Elliott & Fry | |

| Born | 31 May 1838 |

| Died | 28 August 1900 (aged 62) Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Utilitarianism |

| Institutions | University of Cambridge |

Main interests | Economics, ethics, political philosophy |

Notable ideas | Average and total utilitarianism, ethical hedonism, ethical intuitionism, paradox of hedonism |

Henry Sidgwick (

Biography

Henry Sidgwick was born at

Henry Sidgwick was educated at Rugby (where his cousin, subsequently his brother-in-law, Edward White Benson, later Archbishop of Canterbury, was a master), and at Trinity College, Cambridge. While at Trinity, Sidgwick became a member of the Cambridge Apostles. In 1859, he was senior classic, 33rd wrangler, chancellor's medallist and Craven scholar. In the same year, he was elected to a fellowship at Trinity and soon afterwards he became a lecturer in classics there, a post he held for ten years.[3][4] The Sidgwick Site, home to several of the university's arts and humanities faculties, is named after him.

In 1869, he exchanged his lectureship in classics for one in

In 1875, he was appointed praelector on moral and political philosophy at Trinity, and in 1883 he was elected Knightbridge Professor of Philosophy. In 1885, the religious test having been removed, his college once more elected him to a fellowship on the foundation.[3]

Besides his lecturing and literary labours, Sidgwick took an active part in the business of the university and in many forms of social and philanthropic work. He was a member of the General Board of Studies from its foundation in 1882 to 1899; he was also a member of the Council of the Senate of the Indian Civil Service Board and the Local Examinations and Lectures Syndicate and chairman of the Special Board for Moral Science.[3] While at Cambridge Sidgwick taught a young Bertrand Russell.[6]

A 2004 biography of Sidgwick by Bart Schultz sought to establish that Sidgwick was a lifelong homosexual, but it is unknown whether he ever consummated his inclinations. According to the biographer, Sidgwick struggled internally throughout his life with issues of hypocrisy and openness in connection with his own forbidden desires.[2][7]

He was one of the founders and first president of the Society for Psychical Research, and was a member of the Metaphysical Society.[3]

He also promoted the

In 1892 Sidgwick was the president of the second international congress for experimental psychology and delivered the opening address.[8] From the first twelve such international congresses, the International Union of Psychological Science eventually emerged.

Early in 1900 he was forced by ill-health to resign his professorship, and died a few months later., with his wife.

Ethics

| Part of a series on |

| Utilitarianism |

|---|

| Philosophy portal |

Sidgwick summarizes his position in ethics as utilitarianism "on an Intuitional basis".[10] This reflects, and disputes, the rivalry then felt among British philosophers between the philosophies of utilitarianism and ethical intuitionism, which is illustrated, for example, by John Stuart Mill's criticism of ethical intuitionism in the first chapter of his book Utilitarianism.

Sidgwick developed this position due to his dissatisfaction with an inconsistency in Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill's utilitarianism, between what he labels "psychological hedonism" and "ethical hedonism". Psychological hedonism states that everyone always will do what is in their self interest, whereas ethical hedonism states that everyone ought to do what is in the general interest. Sidgwick believed neither Bentham nor Mill had an adequate answer as to how the prescription that someone ought to sacrifice their own interest to the general interest could have any force, given they combined that prescription with the claim that everyone will in fact always pursue their own individual interest. Ethical intuitions, such as those argued for by philosophers such as William Whewell, could, according to Sidgwick, provide the missing force for such normative claims.

For Sidgwick, ethics is about which actions are objectively right.[11] Our knowledge of right and wrong arises from common-sense morality, which lacks a coherent principle at its core.[12] The task of philosophy in general and ethics in particular is not so much to create new knowledge but to systematize existing knowledge.[13] Sidgwick tries to achieve this by formulating methods of ethics, which he defines as rational procedures "for determining right conduct in any particular case".[14][15] He identifies three methods: intuitionism, which involves various independently valid moral principles to determine what ought to be done, and two forms of hedonism, in which rightness only depends on the pleasure and pain following from the action. Hedonism is subdivided into egoistic hedonism, which only takes the agent's own well-being into account, and universal hedonism or utilitarianism, which is concerned with everyone's well-being.[13][14]

As Sidgwick sees it, one of the central issues of ethics is whether these three methods can be harmonized with each other. Sidgwick argues that this is possible for intuitionism and utilitarianism. But a full success of this project is impossible since egoism, which he considers as equally rational, cannot be reconciled with utilitarianism unless religious assumptions are introduced.[14] Such assumptions, for example, the existence of a personal God who rewards and punishes the agent in the afterlife, could reconcile egoism and utilitarianism.[13] But without them, we have to admit a "dualism of practical reason" that constitutes a "fundamental contradiction" in our moral consciousness.[11]

Metaethics

Sidgwick's

Esoteric morality

Sidgwick is closely, and controversially, associated with esoteric morality: the position that a moral system (such as utilitarianism) may be acceptable, but that it is not acceptable for that moral system to be widely taught or accepted.[17]

Philosophical legacy

According to John Rawls, Sidgwick's importance to modern ethics rests with two contributions: providing the most sophisticated defense available of utilitarianism in its classical form, and providing in his comparative methodology an exemplar for how ethics is to be researched as an academic subject.[19] Allen Wood describes Sidgwick-inspired comparative methodology as the "standard model" of research methodology among contemporary ethicists.[20]

Despite his importance to contemporary ethicists, Sidgwick's reputation as a philosopher fell precipitously in the decades following his death, and he would be regarded as a minor figure in philosophy for a large part of the first half of the 20th century. Bart Schultz argues that this negative assessment is explained by the tastes of groups which would be influential at Cambridge in the years following Sidgwick's death:

Economics

Sidgwick worked in economics at a time when the British economics mainstream was undergoing the transition from the

Sidgwick believed self interest to be a centerpiece of human motivation. He believed that this self interest had immense utility in the economic world, and that people should not be blamed for wanting to sell a good for the highest possible price, or buy a good for the lowest possible price. He distinguished though a difference between the ability for an individual to properly judge their own interests and the ability of a group of people to properly come to a point of maximum group happiness. He found two divergences in the outcomes of the decisions of the individual and of the group. One instance of this is the idea that there is more to life than the accumulation of wealth, so it is not always in the best interest of society to simply aim for wealth maximizing results. This effect may be due limitations of the individual, from attributes such as ignorance, immaturity, and disability. This can be a moral judgement, such as the decision to limit the sale of alcohol to an individual out of a concern of their well being. The second instance is the fact that wealth maximizing outcomes for society are simply not always a possibility when individuals within that society are all attempting to maximize their individual wealth. Contradictions are likely to emerge that cause one individual a lower maximum wealth due to another individual's actions, therefore disallowing the possibility of a society-wide wealth maximization. Problems also are possible to occur due to monopoly.[24]

Sidgwick would have a major influence on the development of welfare economics, due to his own work on the subject inspiring Arthur Cecil Pigou's work The Economics of Welfare.[24]

Alfred Marshall, founder of the Cambridge School of economics, would describe Sidgwick as his "spiritual mother and father."[25]

Parapsychology

Sidgwick had a lifelong interest in the paranormal. This interest, combined with his personal struggles with religious belief, motivated his gathering of young colleagues interested in assessing the empirical evidence for paranormal or miraculous phenomena. This gathering would be known as the "Sidgwick Group", and would be a predecessor of the Society for Psychical Research, which would count Sidgwick as founder and first president.[26]

Sidgwick would connect his concerns with parapsychology to his research in ethics. He believed the dualism of practical reason might be solved outside of philosophical ethics if it were shown, empirically, that the recommendations of rational egoism and utilitarianism coincided due to the reward of moral behaviour after death.

According to Bart Schultz, despite Sidgwick's prominent role in institutionalizing parapsychology as a discipline, he had upon it an "overwhelmingly negative, destructive effect, akin to that of recent debunkers of parapsychology"; he and his Sidgwick Group associates became notable for exposing fraud mediums.[27] One such incident was the exposure of the fraud of Eusapia Palladino.[28][29]

Religion

Brought up in the Church of England, Sidgwick drifted away from orthodox Christianity, and as early as 1862 he described himself as a

Works by Sidgwick

- The Ethics of Conformity and Subscription. 1870.

- The Methods of Ethics. London, 1874, 7th edition 1907.

- The Theory of Evolution in its application to Practice, in Mind, Volume I, Number 1 January 1876, 52–67,

- Principles of Political Economy. London, 1883, 3rd edition 1901.

- The Scope and Method of Economic Science. 1885.

- Outlines of the History of Ethics for English Readers. 1886 5th edition 1902 (enlarged from his article Ethics in the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition).

- The Elements of Politics. London, 1891, 4th edition 1919.

- "The Philosophy of Common Sense", in Mind, New Series, Volume IV, Number 14, April 1895, 145–158.

- The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, 1987, v. 2, 58–59.)

- Practical Ethics. London, 1898, 2nd edition 1909.

- Philosophy; its Scope and Relations. London, 1902.

- Lectures on the Ethics of T. H. Green, Mr Herbert Spencer and J. Martineau. 1902.

- The Development of European Polity. 1903, 3rd edition 1920

- Miscellaneous Essays and Addresses. 1904.

- Lectures on the Philosophy of Kant and other philosophical lectures and essays. 1905.

Family

In 1876, Sidgwick married physics researcher Eleanor Mildred Balfour in London. A member of the Cambridge Ladies Dining Society, and later Principal of Newnham College, Cambridge, she was the sister of Arthur Balfour, a future Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. They had no children, and remained married until his death.

See also

- Palm Sunday Case

Citations

- ^ Bryce 1903, pp. 327–342.

- ^ a b Schultz 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Chisholm 1911.

- ^ "Sidgwick, Henry (SGWK855H)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Rawls 1980.

- ISBN 9780671202538.

- ^ Nussbaum 2005.

- ^ "The Congress of Experimental Psychology". The Athenaeum (3380): 198. 6 August 1892.

- ^ Brooke & Leader 1988.

- ^ Sidgwick 1981, p. xxii.

- ^ a b Schultz, Barton (2020). "Henry Sidgwick". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ Duignan, Brian; West, Henry R. "Utilitarianism". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ a b c Borchert, Donald (2006). "Sidgwick, Henry". Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2nd Edition. Macmillan.

- ^ a b c Craig, Edward (1996). "Sidgwick, Henry". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge.

- ^ Honderich, Ted (2005). "Sidgwick, Henry". The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Phillips 2011, pp. 10–13.

- ^ de Lazari-Radek & Singer 2010.

- ^ Williams 2009, p. 291.

- ^ Rawls 1981.

- ^ Wood 2008, p. 45.

- ^ Schultz 2009, p. 4.

- ^ Deigh 2007, p. 439.

- ^ Collini 1992, pp. 340–341.

- ^ a b c Medema 2008.

- ^ Deane 1987.

- ^ Schultz 2009, pp. 275–276.

- ^ Schultz 2019.

- ^ Anonymous 1895.

- ^ Sidgwick 1895.

Sources

- Anonymous (9 November 1895). "Exit Eusapia!". The British Medical Journal. 2 (1819). British Medical Association: 1182.

- Brooke, Christopher Nugent Lawrence; Leader, Damian Riehl (1988). "1: Prologue". A History of the University of Cambridge: 1870–1990. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780521343503.

In 1869 Henry Sidgwick, who had become a devout agnostic, made protest against the survival of religious tests in Cambridge by resigning his Trinity fellowship.

- Bryce, James (1903). "Henry Sidgwick". Studies in Contemporary Biography. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 9780790544946.

- Collini, Stefan (1992). "The ordinary experience of civilized life: Sidgwick's politics and the method of reflective analysis". In Schultz, Bart (ed.). Essays on Henry Sidgwick. Cambridge University Press. pp. 333–368. ISBN 0-521-39151-2.

- Deane, Phyllis (1987). "Sidgwick, Henry". The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics. Vol. 4. pp. 328–329.

- de Lazari-Radek, Katarzyna; Singer, Peter (4 January 2010). "Secrecy in consequentialism: A defence of esoteric morality". Ratio. 23 (1). Wiley: 34–58. .

- Deigh, John (12 November 2007). "Sidgwick's Epistemology". Utilitas. 19 (4). Cambridge University Press: 435–446. S2CID 144210231.

- Medema, Steven G. (1 December 2008). ""Losing My Religion": Sidgwick, Theism, and the Struggle for Utilitarian Ethics in Economic Analysis". History of Political Economy. 40 (5): 189–211. .

- Nussbaum, Martha (6 June 2005). "The Epistemology of the Closet". The Nation. United States.

- Phillips, David(2011). Sidgwickian Ethics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Rawls, John (September 1980). "Kantian Constructivism in Moral Theory". The Journal of Philosophy. 77 (9). The Journal of Philosophy, Inc.: 515–572.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Rawls, John (1981). "Foreword to The Methods of Ethics". The Methods of Ethics (7th ed.). Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company. p. v-vi. ISBN 978-0915145287.

- Schultz, Bart (2009) [2004]. Henry Sidgwick - Eye of the Universe: An Intellectual Biography. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511498336.

- Schultz, Barton (2019). "Henry Sidgwick". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- Sidgwick, Henry (16 November 1895). "Exit Eusapia". The British Medical Journal. 2 (1820). British Medical Association: 1263. S2CID 220131916.

- Sidgwick, Henry (1981) [1907]. The Methods of Ethics (7th ed.). Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0915145287.

- ISBN 978-0-521-09822-9.

- Williams, Bernard (2009) [1982]. "The Point of View of the Universe: Sidgwick and the Ambitions of Ethics". The Sense of the Past: Essays in the History of Philosophy. Princeton University Press. pp. 277–296. ISBN 978-0-691-13408-6.

- ISBN 978-0521671149.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Sidgwick, Henry". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 39.

Further reading

- Blum, Deborah (2006). Ghost hunters : William James and the search for scientific proof of life after death. New York: Penguin Press.

- de Lazari-Radek, Katarzyna; Singer, Peter (2014). The Point of View of the Universe: Sidgwick and Contemporary Ethics. Oxford University Press.

- Geninet, Hortense (2009). Geninet, Hortense (ed.). Politiques comparées, Henry Sidgwick et la politique moderne dans les "Éléments Politiques" (in French). France. ISBN 978-2-7466-1043-9.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - Nakano-Okuno, Mariko (2011). Sidgwick and Contemporary Utilitarianism. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-32178-6.

- Schneewind, Jerome (1977). Sidgwick's Ethics and Victorian Moral Philosophy. Clarendon Press.

- Shaver, Robert (2009) [1990]. Rational Egoism: A Selective and Critical History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521119962. – Study of rational egoism that focuses on Sidgwick's thought on the subject, alongside that of Thomas Hobbes.

External links

- Works by Henry Sidgwick at Project Gutenberg

- Henry Sidgwick Website

- Official website of the 2nd International congress : Henry Sidgwick Ethics, Psychics, Politics. University of Catania – Italy

- Henry Sidgwick. Comprehensive list of online writings by and about Sidgwick.

- Contains Sidgwick's "Methods of Ethics", modified for easier reading

- Henry Sidgwick, Leslie Stephen, Mind, New Series, Vol. 10, No. 37 (January 1901), pp. 1–17 [At Internet Archive]

- The Ethical System of Henry Sidgwick, James Seth, Mind, New Series, Vol. 10, No. 38 (April 1901), pp. 172–187 [At Internet Archive]

- Henry Sidgwick, biographical profile, including quotes and further resources, at Utilitarianism.net.