Rajasaurus

| Rajasaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed skull, Regional Museum of Natural History, Bhopal | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Abelisauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Majungasaurinae |

| Genus: | †Rajasaurus Wilson et al., 2003 |

| Species: | †R. narmadensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Rajasaurus narmadensis Wilson et al., 2003

| |

Rajasaurus (meaning "

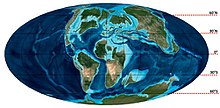

India at this time was an island, due to the break-up of the

Discovery and naming

The Lameta Formation was first discovered in 1981 by geologists working for the Geological Survey of India (GSI), G. N. Dwivedi and Dhananjay Mahendrakumar Mohabey, after being given limestone structures–later recognised as dinosaur eggs–by workers of the ACC Cement Quarry in the village of Rahioli near the city Balasinor in the Gujarat state of western India. The remains of Rajasaurus were found in this fossil-rich limestone bed to which GSI geologist Suresh Srivastava was assigned to excavate on two separate trips from 1982–1983 and 1983–1984. In 2001, teams from the American Institute of Indian Studies and the National Geographic Society, with the support of the Panjab University, joined the study in order to reconstruct the excavated remains. Fragments of Rajasaurus were also found near Jabalpur in Madhya Pradesh in the northern part of the Lameta Formation, namely a piece of the upper jaw.[1] Rajasaurus was then formally described in 2003 by geologist Jeffrey A. Wilson and colleagues.[2]

The

The

Description

In 2010, palaeontologist

On the braincase, only the left sides of the

Rajasaurus had a low horn on its forehead that is primarily made of nasal bone more than frontal, unlike the horn on Majungasaurus. The horn in life was probably the same size as the fossilised horn, unlike in Carnotaurus where in life the horn was extended by a thickened layer skin. Though Rajasaurus did have a thickened layer of skin, it probably did not add to the overall length of the horn.[7] A trough-like groove bordered by a raised wall is present where the frontal meets the nasal, decreasing in height and width towards the midline, serving to support the horn on the nasal.[2]

Only one

The part of the hip that juts out to attach to the

Classification

Wilson, in 2003, assigned Rajasaurus to the subfamily

In 2014, the subfamily

The following cladogram was recovered by Tortosa (2014):[14]

Rajasaurus is distinguished from other genera by its single forehead horn (though Majungasaurus also only has one), the elongated supratemporal fenestrae (holes in the upper rear of the skull), and the ilia bones on the hip which feature a ridge separating the brevis shelf from the hip joint.[2]

Palaeobiology

The horn of Rajasaurus could have been used for

Abelisaurids may have been ambush predators, using a bite-and-hold tactic to hunt large prey. The leg bones of Majungasaurus are comparatively short to other similarly-sized theropods, suggesting the dinosaur was comparatively slower–this same condition is seen in Rajasaurus. However, ceratosaurs may have been able to rapidly accelerate.[7][16]

Palaeoecology

Rajasaurus has been found in the Lameta Formation, a rock unit

India, by the Late Cretaceous, had separated from Madagascar and South America during the break-up of Gondwana, and Rajasaurus lived on an isolated island, likely causing

Several dinosaurs have been described from the Lameta Formation, such as the

The dinosaurs in India probably all went extinct due to volcanic activity around 350,000 years before the

Cultural significance

The Gujarat state has declared the fossil site in Balasinor a "dinosaur park," sometimes called the "Jurassic Park of India" in reference to the

See also

- Timeline of ceratosaur research

- Dryptosauroides

- Compsosuchus

- Jubbulpuria

- Ornithomimoides

- Orthogoniosaurus

References

- ^ a b c "Rajasaurus narmadensis – India's own dinosaur emerges from oblivion" (PDF). Geological Survey of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2008. Retrieved 8 April 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Wilson, J. A.; Sereno, P. C.; Srivastava, S.; Bhatt, D. K.; Khosla, A.; Sahni, A. (2003). "A new abelisaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Lameta Formation (Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) of India" (PDF). Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology University of Michigan. 31 (1): 1–42.

- ^ S2CID 30068953. Archived from the original(PDF) on 22 May 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-691-13720-9.

- .

- S2CID 130262308.

- ^ PMID 29950661.

- ^ J.A. Wilson, P.C. Sereno, S. Srivastava, D.K. Bhatt, A. Khosla and A. Sahni, 2003, "A new abelisaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Lameta Formation (Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) of India", Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan 31(1): 1-42

- ISBN 978-0-691-18031-1.

- S2CID 129240095.

- ^ Mathur, U. B. ubmathur (2004). "Rajasaurus narmadaensis" (PDF). Current Science. 86 (6).

- S2CID 13345182.

- PMID 15306329.

- ^ .

- ^ Kapur, V. V.; Khosla, A. (2016). "Late Cretaceous terrestrial biota from India with special reference to vertebrates and their implications for biogeographic connections". Cretaceous Period: Biotic Diversity and Biogeography. 71: 161–172.

- PMID 22043292.

- .

- ^ Mohabey, D. M. (1996). "Depositional environment of Lameta Formation (late Cretaceous) of Nand-Dongargaon inland basin, Maharashtra: the fossil and lithological evidences". Memoirs of the Geological Survey of India. 37: 1–36.

- .

- ^ Lovgren, S. (13 August 2003). "New Dinosaur Species Found in India". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 11 December 2003. Retrieved 8 April 2009.

- S2CID 135418472.

- PMID 20209142.

- ^ "Rajasaurus narmadensis – A new Indian dinosaur" (PDF). Current Science. Vol. 85, no. 12. 2003. p. 1661.

- S2CID 83532299.

- S2CID 86208659.

- ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- ^ Mohabey, D. M.; Samant, B. (2013). "Deccan continental flood basalt eruption terminated Indian dinosaurs before the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary". Geological Society of India Special Publication (1): 260–267.

- ^ "The dinosaur wonders of India's Jurassic Park". BBC News. 11 May 2010. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ^ Bhattacharya, S. (16 January 2013). "India's Jurassic Park hopes 'princely lizards' will attract tourists". The National. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ^ "Rajasaurus River Adventure". imagica. Archived from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

External links

- "Rajasaurus stalked the banks of Narmada" The Hindu, 2003

Media related to Rajasaurus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rajasaurus at Wikimedia Commons