Giraffe

| Giraffes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Masai giraffe (Giraffa tippelskirchi) in Mikumi National Park, Tanzania | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Giraffidae |

| Genus: | Giraffa Brisson, 1762 |

| Species | |

| |

| Distribution of the giraffe | |

The giraffe is a large

The giraffe's distinguishing characteristics are its extremely long neck and legs, horn-like

The giraffe has intrigued various ancient and modern cultures for its peculiar appearance and has often been featured in paintings, books, and cartoons. It is classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as vulnerable to extinction. It has been extirpated from many parts of its former range. Giraffes are still found in many national parks and game reserves, but estimates as of 2016 indicate there are approximately 97,500 members of Giraffa in the wild. More than 1,600 were kept in zoos in 2010.

Etymology

The name "giraffe" has its earliest known origins in the

"Camelopard" (/kəˈmɛləˌpɑːrd/) is an archaic English name for the giraffe; it derives from the Ancient Greek καμηλοπάρδαλις (kamēlopárdalis), from κάμηλος (kámēlos), "camel", and πάρδαλις (párdalis), "leopard", referring to its camel-like shape and leopard-like colouration.[4][5]

Taxonomy

Evolution

The giraffe is one of only two living genera of the family Giraffidae in the order

The family Giraffidae was once much more extensive, with over 10 fossil genera described.[6] The elongation of the neck appears to have started early in the giraffe lineage. Comparisons between giraffes and their ancient relatives suggest vertebrae close to the skull lengthened earlier, followed by lengthening of vertebrae further down.[8] One early giraffid ancestor was Canthumeryx, which has been dated variously to have lived 25 to 20 million years ago, 17–15 mya or 18–14.3 mya and whose deposits have been found in Libya. This animal resembled an antelope and had a medium-sized, lightly built body. Giraffokeryx appeared 15–12 mya on the Indian subcontinent and resembled an okapi or a small giraffe, and had a longer neck and similar ossicones.[6] Giraffokeryx may have shared a clade with more massively built giraffids like Sivatherium and Bramatherium.[8]

Giraffids like Palaeotragus, Shansitherium and Samotherium appeared 14 mya and lived throughout Africa and Eurasia. These animals had broader skulls with reduced frontal cavities.[6][8] Paleotragus resembled the okapi and may have been its ancestor.[6] Others find that the okapi lineage diverged earlier, before Giraffokeryx.[8] Samotherium was a particularly important transitional fossil in the giraffe lineage, as the length and structure of its cervical vertebrae were between those of a modern giraffe and an okapi, and its neck posture was likely similar to the former's.[9] Bohlinia, which first appeared in southeastern Europe and lived 9–7 mya, was likely a direct ancestor of the giraffe. Bohlinia closely resembled modern giraffes, having a long neck and legs and similar ossicones and dentition.[6]

Bohlinia colonised China and northern India and produced the Giraffa, which, around 7 million years ago, reached Africa. Climate changes led to the extinction of the Asian giraffes, while the African giraffes survived and radiated into new species. Living giraffes appear to have arisen around 1 million years ago in eastern Africa during the Pleistocene.[6] Some biologists suggest the modern giraffes descended from G. jumae;[10] others find G. gracilis a more likely candidate. G. jumae was larger and more robust, while G. gracilis was smaller and more slender.[6]

The changes from extensive forests to more open

The giraffe genome is around 2.9 billion

Species and subspecies

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) currently recognises only one species of giraffe with nine subspecies.[1]

Carl Linnaeus originally classified living giraffes as one species in 1758. He gave it the binomial name Cervus camelopardalis. Mathurin Jacques Brisson coined the generic name Giraffa in 1762.[17] During the 1900s, various taxonomies with two or three species were proposed.[18] A 2007 study on the genetics of giraffes using mitochondrial DNA suggested at least six lineages could be recognised as species.[16] A 2011 study using detailed analyses of the morphology of giraffes, and application of the phylogenetic species concept, described eight species of living giraffes.[19] A 2016 study also concluded that living giraffes consist of multiple species. The researchers suggested the existence of four species, which have not exchanged genetic information between each other for one to two million years.[20]

A 2020 study showed that depending on the method chosen, different taxonomic hypotheses recognizing from two to six species can be considered for the genus Giraffa. That study also found that multi-species coalescent methods can lead to taxonomic over-splitting, as those methods delimit geographic structures rather than species. The three-species hypothesis, which recognises G. camelopardalis, G. giraffa, and G. tippelskirchi, is highly supported by phylogenetic analyses and also corroborated by most population genetic and multi-species coalescent analyses.[21] A 2021 whole genome sequencing study suggests the existence of four distinct species and seven subspecies,[22] which was supported by a 2024 study of cranial morphology.[23] A 2024 study found a higher amount of ancient gene flow than expected between populations.[24]

The cladogram below shows the phylogenetic relationship between the four proposed species and seven subspecies based on a 2021 genome analysis.[22] The eight lineages correspond to eight traditional subspecies in the one-species hypothesis. The Rothschild giraffe is subsumed into G. camelopardalis camelopardalis.

|

The following table compares the different hypotheses for giraffe species. The description column shows the traditional nine subspecies in the one-species hypothesis.[1][25]

| Description | Image | Eight species taxonomy[19] | Four species taxonomy[20][22] | Three species taxonomy[21] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The |

|

Kordofan giraffe (G. antiquorum)[29] |

Northern giraffe (G. camelopardalis) Three or four subspecies:

| |

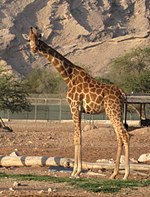

| The Nubian giraffe (G. c. camelopardalis), is found in eastern South Sudan and southwestern Ethiopia, in addition to Kenya and Uganda.[1] It has sharp-edged chestnut-coloured spots surrounded by mostly white lines, while undersides lack spotting. A lump is prominent in the middle of the male's head.[27]: 51 Around 2,150 are thought to remain in the wild, with another 1,500 individuals belonging to the Rothschild's ecotype.[1] With the addition of Rothschild's giraffe to the Nubian subspecies, the Nubian giraffe is very common in captivity, although the original phenotype is rare — a group is kept at Al Ain Zoo in the United Arab Emirates.[30] In 2003, this group numbered 14.[31] |

|

Nubian giraffe (G. camelopardalis)[25] Also known as Baringo giraffe or Ugandan giraffe Two subspecies:

| ||

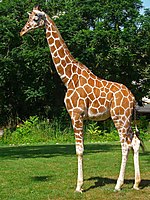

| Rothschild's giraffe (G. c. rothschildi) may be an ecotype of G. camelopardalis. Its range includes parts of Uganda and Kenya.[1] Its presence in South Sudan is uncertain.[32] This giraffe has large dark patches with normally well-defined edges but sometimes split. The dark spots may also have swirls of pale colour within them. Spotting rarely reaches below the hocks and rarely to the hooves. This ecotype may also develop five "horns".[27]: 53 Around 1,500 individuals are believed to remain in the wild,[1] and more than 450 are living in zoos.[28] According to genetic analysis circa September 2016, it is conspecific with the Nubian giraffe (G. c. camelopardalis).[20] |

| |||

| The pelage (fur) than other subspecies,[33]: 322 with red lobe-shaped blotches that reach under the hocks. The ossicones are more erect than in other subspecies, and males have well-developed median lumps.[27]: 52–53 It is the most endangered subspecies within Giraffa, with 400 individuals remaining in the wild.[1] Giraffes in Cameroon were formerly believed to belong to this species, but are actually G. c. antiquorum. This error resulted in some confusion over its status in zoos, but in 2007 it was established that all "G. c. peralta" kept in European zoos are actually G. c. antiquorum. The same 2007 study found that the West African giraffe was more closely related to Rothschild's giraffe than the Kordofan, and its ancestor may have migrated from eastern to northern Africa and then west as the Sahara Desert spread. At its largest, Lake Chad may have acted as a boundary between the West African and Kordofan giraffes during the Holocene (before 5000 BC).[26]

|

|

West African giraffe (G. peralta),[34] | ||

| The International Species Information System records, more than 450 are living in zoos.[28] A 2024 study found that the reticulated giraffe is the result of hybridisation between northern and southern giraffe lineages.[24]

|

|

Reticulated giraffe (G. reticulata),[35] Also known as Somali giraffe |

||

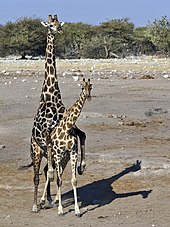

| The Namib Desert and Etosha National Park populations form a separate subspecies.[40] This subspecies is white with large brown blotches with pointed or cut edges. The spotting pattern extends throughout the legs but not the upper part of the face. The neck and rump patches tend to be fairly small. The subspecies also has a white ear mark.[27]: 51 About 13,000 animals are estimated to remain in the wild,[1] and about 20 are living in zoos.[28]

|

|

Angolan giraffe (G. angolensis) Also known as Namibian giraffe |

Southern giraffe (G. giraffa)

Two subspecies:

| |

| The South African giraffe (G. c. giraffa) is found in northern South Africa, southern Botswana, northern Botswana and southwestern Mozambique.[1][38][39] It has a tawny background colour marked with dark, somewhat rounded patches "with some fine projections". The spots extend down the legs, growing smaller as they do. The median lump of males is relatively small.[27]: 52 A maximum of 31,500 are estimated to remain in the wild,[1] and around 45 are living in zoos.[28] |

|

South African giraffe (G. giraffa)[41] Also known as Cape giraffe | ||

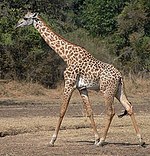

| The Masai giraffe (G. c. tippelskirchi) can be found in central and southern Kenya and in Tanzania.[1] Its coat patterns are highly diverse, with spots ranging from mostly rounded and smooth-edged to oval-shaped and incised or loped-edged.[42] A median lump is usually present in males.[27]: 54 [43] A total of 32,550 are thought to remain in the wild,[1] and about 100 are living in zoos.[28] |

|

Masai giraffe (G. tippelskirchi)[36] Also known as |

Masai giraffe (G. tippelskirchi)

Two subspecies:

| |

Thornicroft's giraffe (G. c. thornicrofti) is restricted to the Luangwa Valley in eastern Zambia.[1] It has notched and somewhat star-shaped patches which and may or may not extend across the legs. The median lump of males is modestly sized.[27]: 54 No more than 550 remain in the wild,[1] with none in zoos.[28] It was named after Harry Scott Thornicroft.[36]

|

|

Thornicroft's giraffe ("G. thornicrofti") Also known as Luangwa giraffe or Rhodesian giraffe | ||

The first extinct species to be described was Giraffa sivalensis from Pakistan, the holotype of which was reevaluated as a vertebra of separate species within the genus that was initially described as a fossil of the living giraffe.[44] Another extinct species Giraffa punjabiensis is known from Pakistan.[45] Four other valid extinct species of Giraffa known from Africa are Giraffa gracilis, Giraffa jumae, Giraffa pygmaea and Giraffa stillei.[8] "G." pomeli from Algeria and Tunisia is not a species of Giraffinae, but a species of Palaeotraginae related to Mitilanotherium.[46]

Anatomy

Fully grown giraffes stand 4.3–5.7 m (14–19 ft) tall, with males taller than females.[47] The average weight is 1,192 kg (2,628 lb) for an adult male and 828 kg (1,825 lb) for an adult female.[48] Despite its long neck and legs, its body is relatively short.[49]: 66 The skin is mostly gray[48] or tan,[50] and can reach a thickness of 20 mm (0.79 in).[51]: 87 The 80–100 cm (31–39 in) long[36] tail ends in a long, dark tuft of hair and is used as a defense against insects.[51]: 94

The coat has dark blotches or patches, which can be orange, chestnut, brown, or nearly black, surrounded by light hair, usually white or cream coloured.[52] Male giraffes become darker as they grow old.[43] The coat pattern has been claimed to serve as camouflage in the light and shade patterns of savannah woodlands.[36] When standing among trees and bushes, they are hard to see at even a few metres distance. However, adult giraffes move about to gain the best view of an approaching predator, relying on their size and ability to defend themselves rather than on camouflage, which may be more important for calves.[6] Each giraffe has a unique coat pattern.[53][54] Calves inherit some coat pattern traits from their mothers, and variation in some spot traits is correlated with calf survival.[42] The skin under the blotches may regulate the animal's body temperature, being sites for complex blood vessel systems and large sweat glands.[55] Spotless or solid-color giraffes are very rare, but have been observed.[56][57]

The fur may give the animal chemical defense, as its parasite repellents give it a characteristic scent. At least 11 main

Head

Both sexes have prominent horn-like structures called ossicones, which can reach 13.5 cm (5.3 in). They are formed from ossified cartilage, covered in skin, and fused to the skull at the parietal bones.[43][51]: 95–97 Being vascularised, the ossicones may have a role in thermoregulation,[55] and are used in combat between males.[59] Appearance is a reliable guide to the sex or age of a giraffe: the ossicones of females and young are thin and display tufts of hair on top, whereas those of adult males tend to be bald and knobbed on top.[43] A lump, which is more prominent in males, emerges in the middle of the skull.[17] Males develop calcium deposits that form bumps on their skulls as they age.[52] Multiple sinuses lighten a giraffe's skull.[51]: 103 However, as males age, their skulls become heavier and more club-like, helping them become more dominant in combat.[43] The occipital condyles at the bottom of the skull allow the animal to tip its head over 90 degrees and grab food on the branches directly above them with the tongue.[51]: 103, 110 [17]

With eyes located on the sides of the head, the giraffe has a broad

Neck

The giraffe has an extremely elongated neck, which can be up to 2.4 m (7.9 ft) in length.

The giraffe's neck vertebrae have

There are several hypotheses regarding the evolutionary origin and maintenance of elongation in giraffe necks.

Another theory, the sexual selection hypothesis, proposes that long necks evolved as a secondary sexual characteristic, giving males an advantage in "necking" contests (see below) to establish dominance and obtain access to sexually receptive females.[10] In support of this theory, some studies have stated that necks are longer and heavier for males than females of the same age,[10][59] and that males do not employ other forms of combat.[10] However, a 2024 study found that, while males have thicker necks, females actually have proportionally longer ones, which is likely because of their greater need to find more food to sustain themselves and their dependent young.[70] It has also been proposed that the neck serves to give the animal greater vigilance.[71][72]

Legs, locomotion and posture

The front legs tend to be longer than the hind legs,[51]: 109 and males have proportionally longer front legs than females, which gives them better support when swinging their necks during fights.[70] The leg bones lack first, second and fifth metapodials.[51]: 109 It appears that a suspensory ligament allows the lanky legs to support the animal's great weight.[73] The hooves of large male giraffes reach 31 cm × 23 cm (12.2 in × 9.1 in) in diameter.[51]: 98 The fetlock of the leg is low to the ground, allowing the hoof to better support the animal's weight. Giraffes lack dewclaws and interdigital glands. While the pelvis is relatively short, the ilium has stretched-out crests.[17]

A giraffe has only two gaits: walking and galloping. Walking is done by moving the legs on one side of the body, then doing the same on the other side.[43] When galloping, the hind legs move around the front legs before the latter move forward,[52] and the tail will curl up.[43] The movements of the head and neck provide balance and control momentum while galloping.[33]: 327–29 The giraffe can reach a sprint speed of up to 60 km/h (37 mph),[74] and can sustain 50 km/h (31 mph) for several kilometres.[75] Giraffes would probably not be competent swimmers as their long legs would be highly cumbersome in the water,[76] although they might be able to float.[77] When swimming, the thorax would be weighed down by the front legs, making it difficult for the animal to move its neck and legs in harmony[76][77] or keep its head above the water's surface.[76]

A giraffe rests by lying with its body on top of its folded legs.

Internal systems

In mammals, the left recurrent laryngeal nerve is longer than the right; in the giraffe, it is over 30 cm (12 in) longer. These nerves are longer in the giraffe than in any other living animal;[79] the left nerve is over 2 m (6 ft 7 in) long.[80] Each nerve cell in this path begins in the brainstem and passes down the neck along the vagus nerve, then branches off into the recurrent laryngeal nerve which passes back up the neck to the larynx. Thus, these nerve cells have a length of nearly 5 m (16 ft) in the largest giraffes.[79] Despite its long neck and large skull, the brain of the giraffe is typical for an ungulate.[81] Evaporative heat loss in the nasal passages keep the giraffe's brain cool.[55] The shape of the skeleton gives the giraffe a small lung volume relative to its mass. Its long neck gives it a large amount of dead space, though this is limited by its narrow windpipe. The giraffe also has a high tidal volume, so the balance of dead space and tidal volume is much the same as other mammals. The animal can still provide enough oxygen for its tissues, and it can increase its respiratory rate and oxygen diffusion when running.[82]

The giraffe's

Giraffes have

Behaviour and ecology

Habitat and feeding

Giraffes usually inhabit savannahs and open

During the wet season, food is abundant and giraffes are more spread out, while during the dry season, they gather around the remaining evergreen trees and bushes.[89] Mothers tend to feed in open areas, presumably to make it easier to detect predators, although this may reduce their feeding efficiency.[68] As a ruminant, the giraffe first chews its food, then swallows it for processing and then visibly passes the half-digested cud up the neck and back into the mouth to chew again.[49]: 78–79 The giraffe requires less food than many other herbivores because the foliage it eats has more concentrated nutrients and it has a more efficient digestive system.[89] The animal's faeces come in the form of small pellets.[17] When it has access to water, a giraffe will go no more than three days without drinking.[43]

Giraffes have a great effect on the trees that they feed on, delaying the growth of young trees for some years and giving "waistlines" to particularly tall trees. Feeding is at its highest during the first and last hours of daytime. Between these hours, giraffes mostly stand and ruminate. Rumination is the dominant activity during the night, when it is mostly done lying down.[43]

Social life

Giraffes usually form groups that vary in size and composition according to ecological, anthropogenic, temporal, and social factors.[90] Traditionally, the composition of these groups had been described as open and ever-changing.[91] For research purposes, a "group" has been defined as "a collection of individuals that are less than a kilometre apart and moving in the same general direction".[92] More recent studies have found that giraffes have long-lasting social groups or cliques based on kinship, sex or other factors, and these groups regularly associate with other groups in larger communities or sub-communities within a fission–fusion society.[93][94][95][96] Proximity to humans can disrupt social arrangements.[93] Masai giraffes in Tanzania sort themselves into different subpopulations of 60–90 adult females with overlapping ranges, each of which differ in reproductive rates and calf mortality.[97] Dispersal is male biased, and can include spatial and/or social dispersal.[98] Adult female subpopulations are connected by males into super communities of around 300 animals.[99]

The number of giraffes in a group can range from one up to 66 individuals.

Early biologists suggested giraffes were mute and unable to create enough air flow to vibrate their

Reproduction and parental care

Reproduction in giraffes is broadly

Male giraffes assess female fertility by tasting the female's urine to detect oestrus, in a multi-step process known as the flehmen response.[92][100] Once an oestrous female is detected, the male will attempt to court her. When courting, dominant males will keep subordinate ones at bay.[100] A courting male may lick a female's tail, lay his head and neck on her body or nudge her with his ossicones. During copulation, the male stands on his hind legs with his head held up and his front legs resting on the female's sides.[43]

Giraffe

Mothers with calves will gather in nursery herds, moving or browsing together. Mothers in such a group may sometimes leave their calves with one female while they forage and drink elsewhere. This is known as a "calving pool".[109] Calves are at risk of predation, and a mother giraffe will stand over them and kick at an approaching predator.[43] Females watching calving pools will only alert their own young if they detect a disturbance, although the others will take notice and follow.[109] Allo-sucking, where a calf will suckle a female other than its mother, has been recorded in both wild and captive giraffes.[110][111] Calves first ruminate at four to six months and stop nursing at six to eight months. Young may not reach independence until they are 14 months old.[51]: 49 Females are able to reproduce at four years of age,[43] while spermatogenesis in males begins at three to four years of age.[112] Males must wait until they are at least seven years old to gain the opportunity to mate.[43]

Necking

Male giraffes use their necks as

After a duel, it is common for two male giraffes to caress and court each other. Such interactions between males have been found to be more frequent than heterosexual coupling.[113] In one study, up to 94 percent of observed mounting incidents took place between males. The proportion of same-sex activities varied from 30 to 75 percent. Only one percent of same-sex mounting incidents occurred between females.[114]

Mortality and health

Giraffes have high adult survival probability,[115] and an unusually long lifespan compared to other ruminants, up to 38 years.[116] Adult female survival is significantly correlated with the number of social associations.[117] Because of their size, eyesight and powerful kicks, adult giraffes are mostly safe from predation,[43] with lions being their only major threats.[51]: 55 Calves are much more vulnerable than adults and are also preyed on by leopards, spotted hyenas and wild dogs.[52] A quarter to a half of giraffe calves reach adulthood.[115][118] Calf survival varies according to the season of birth, with calves born during the dry season having higher survival rates.[119]

The local, seasonal presence of large herds of migratory wildebeests and zebras reduces predation pressure on giraffe calves and increases their survival probability.[120] In turn, it has been suggested that other ungulates may benefit from associating with giraffes, as their height allows them to spot predators from further away. Zebras were found to assess predation risk by watching giraffes and spend less time looking around when giraffes are present.[121]

Some parasites feed on giraffes. They are often

Human relations

Cultural significance

With its lanky build and spotted coat, the giraffe has been a source of fascination throughout human history, and its image is widespread in culture. It has represented flexibility, far-sightedness, femininity, fragility, passivity, grace, beauty and the continent of Africa itself.[125]: 7, 116

Giraffes were depicted in art throughout the African continent,.

Giraffes have a presence in modern

The giraffe has also been used for some scientific experiments and discoveries. Scientists have used the properties of giraffe skin as a model for

Captivity

The Egyptians were among the earliest people to keep giraffes in captivity and shipped them around the Mediterranean.

Individual captive giraffes were given celebrity status throughout history. In 1414, a giraffe from

Giraffes have become popular attractions in modern zoos, though keeping them is difficult as they prefer large areas and need to eat large amounts of browse. Captive giraffes in North America and Europe appear to have a higher mortality rate than in the wild, the most common causes being poor husbandry, nutrition, and management.[51]: 153 Giraffes in zoos display stereotypical behaviours, particularly the licking of inanimate objects and pacing.[51]: 164 Zookeepers may offer various activities to stimulate giraffes, including training them to take food from visitors.[51]: 167, 176 Stables for giraffes are built particularly high to accommodate their height.[51]: 183

Exploitation

Giraffes were probably common targets for hunters throughout Africa.

Conservation status

In 2016, giraffes were assessed as Vulnerable from a conservation perspective by the IUCN.[1] In 1985, it was estimated there were 155,000 giraffes in the wild. This declined to over 140,000 in 1999.[134] Estimates as of 2016 indicate there are approximately 97,500 members of Giraffa in the wild.[135][136] The Masai and reticulated subspecies are endangered,[137][138] and the Rothschild subspecies is near threatened.[32] The Nubian subspecies is critically endangered.[139]

The primary causes for giraffe population declines are habitat loss and direct killing for bushmeat markets. Giraffes have been extirpated from much of their historic range, including Eritrea, Guinea, Mauritania and Senegal.[1] They may also have disappeared from Angola, Mali, and Nigeria, but have been introduced to Rwanda and Eswatini.[1][139] As of 2010[update], there were more than 1,600 in captivity at Species360-registered zoos.[28] Habitat destruction has hurt the giraffe. In the Sahel, the need for firewood and grazing room for livestock has led to deforestation. Normally, giraffes can coexist with livestock, since they avoid direct competition by feeding above them.[36] In 2017, severe droughts in northern Kenya led to increased tensions over land and the killing of wildlife by herders, with giraffe populations being particularly hit.[140]

Protected areas like national parks provide important habitat and anti-

See also

- Fauna of Africa

- Giraffe Centre

- Giraffe Manor - hotel in Nairobi with giraffes

References

- ^ . Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Giraffe". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ISBN 9789637094545. Archivedfrom the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ "Definition of CAMELOPARD". m-w.com. Encyclopædia Britannica: Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- ^ "Definition of camelopard". Dictionary of Medieval Terms and Phrases. Archived from the original on 4 September 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- ^ S2CID 6522531.

- PMID 31221828.

- ^ PMID 26587249.

- ^ PMID 26716010.

- ^ S2CID 84406669. Archived from the original(PDF) on 23 August 2004.

- JSTOR 2097187.

- S2CID 4335003.

- ^ .

- ^ from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- PMID 27187213.

- ^ PMID 18154651.

- ^ JSTOR 3503830. Archived from the original(PDF) on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- from the original on 3 April 2021. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ^ ISBN 9781421400938. Archivedfrom the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ S2CID 3991170.

- ^ PMID 32053589.

- ^ PMID 33957077.

- PMID 39700177.

- ^ PMID 38479386.

- ^ a b Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema Naturæ.

- ^ PMID 17434121.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Seymour, R. (2001). Patterns of subspecies diversity in the giraffe, Giraffa camelopardalis (L. 1758): comparison of systematic methods and their implications for conservation policy (Ph.D. thesis).

- ^ ISIS. 2010. Archived from the originalon 6 July 2010. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ Swaison 1835. Camelopardalis antiquorum. Bagger el Homer, Kordofan, about 10° N, 28° E (as fixed by Harper, 1940)

- ^ "Exhibits". Al Ain Zoo. 25 February 2003. Archived from the original on 29 November 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ "Nubian giraffe born in Al Ain zoo". UAE Interact. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- ^ . Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-226-43722-4.

- ^ Fennessy, J.; Marais, A.; Tutchings, A. (2018). "Giraffa camelopardalis ssp. peralta". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T136913A51140803.

- from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7607-1969-5.

- ^ "For the first time in decades, Angolan giraffes now populate a park in Angola". NPR. 2023. Archived from the original on 12 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023., Megan Lim, NPR, 11 July 2023

- ^ PMID 25927851.

- ^ S2CID 90395544.

- .

- ISBN 9789061918677. Archivedfrom the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ PMID 30310743.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-520-08085-0.

- PMID 26290791.

- S2CID 18408360.

- ISBN 9780520257214.

- ^ ISBN 978-0801857898. Archivedfrom the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-84418-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7614-7882-9.

- ^ Langley, L. (2017). "Do zebras have stripes on their skin?". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-1107610170.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8018-7135-1.

- from the original on 14 December 2022.

- from the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ Fine Maron, Dina (12 September 2023). "Another rare spotless giraffe found—the first ever seen in the wild". National Geographic. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ Romo, Vanessa; Jones, Dustin (6 September 2023). "A rare spotless giraffe gets a name to match". NPR. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- .

- ^ .

- S2CID 219292664.

- ISBN 978-0520266858.

- PMID 23638372.

- ^ PMID 20700891.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2009.

- ^ doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1990.tb01136.x. Archived from the original(PDF) on 10 November 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- from the original on 2 June 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- S2CID 18821024. Archived from the original(PDF) on 10 November 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- ^ doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1991.tb01190.x. Archived from the original(PDF) on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- S2CID 83652889.

- ^ .

- S2CID 4145785.

- PMID 27626454.

- ^ Wood, C. (2014). "Groovy giraffes...distinct bone structures keep these animals upright". Society for Experimental Biology. Archived from the original on 25 November 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1993.tb02626.x. Archived from the original(PDF) on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ISBN 978-1-61530-336-6.

- ^ PMID 20385144.

- ^ from the original on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- S2CID 34605791.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-521-45321-9.

- S2CID 3634656.

- (PDF) from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- .

- (PDF) from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- (PDF) from the original on 22 July 2018.

- .

- S2CID 20040338.

- ^ Fennessy, J. (2004). Ecology of desert-dwelling giraffe Giraffa camelopardalis angolensis in northwestern Namibia (PhD thesis). University of Sydney. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-408355-4.

- ^ from the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2000.tb00588.x. Archived from the original(PDF) on 6 November 2013.

- ^ .

- ^ PMID 32515083.

- .

- ^ S2CID 53176817.

- ^ .

- S2CID 233600744. Archived from the originalon 8 March 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- PMC 9291750.

- S2CID 237949827.

- ^ .

- (PDF) from the original on 10 February 2020.

- ^ .

- PMID 29316966.

- PMID 26353836.

- .

- ^ from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- S2CID 45843281.

- PMID 23925833.

- ^ doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1977.tb00074.x. Archived from the originalon 12 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- S2CID 91472891.

- PMID 33782483.

- (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-312-19239-6.

- ^ ISBN 9780124095489.

- S2CID 10687135.

- PMID 33563118.

- S2CID 87117946.

- from the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- PMID 28031792.

- .

- S2CID 10736316.

- S2CID 46776142.

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-1-86189-764-0.

- Bradshaw Foundation. Archivedfrom the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ISSN 1612-1651.

- ISBN 9781118587478.

- S2CID 13488215. Archived from the originalon 23 September 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- JSTOR 40979758.

- (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2008.

- ISBN 0 349 11127 8pps. 20–21.

- ^ Ian Cunnison (1958). "Giraffe hunting among the Humr tribe". Sudan Notes and Records. 39.

- ^ "Giraffe – The Facts: Current giraffe status?". Giraffe Conservation Foundation. Archived from the original on 19 March 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- ^ Matt McGrath (8 December 2016). "Giraffes facing 'silent extinction' as population plunges". BBC News. Archived from the original on 21 May 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ "New bird species and giraffe under threat – IUCN Red List". 8 December 2016. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- .

- .

- ^ .

- from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- PMID 29867255.

- ISBN 978-0-7069-2822-8.

- ISBN 978-1-4008-5280-2. Archivedfrom the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ "National Symbols: National Animal". tanzania.go.tz. Tanzania Government Portal. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ "Chimpanzees among 33 breeds selected for special protection". BBC News. 28 October 2017. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ^ "Good News for Giraffes at CITES CoP18 > Newsroom". newsroom.wcs.org. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- .

- doi:10.3354/esr01022. Archivedfrom the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- S2CID 87384776.

External links

- Official website of the Giraffe Conservation Foundation