List of largest reptiles

This list of largest reptiles takes into consideration both body length and mass of large

The saltwater crocodile is considered to be the largest extant reptile, verified at up to 6.32 m (20.7 ft) in length and around 1,000–1,500 kg (2,200–3,300 lb) in mass.[2] Larger specimens have been reported albeit not fully verified,[3] the maximum of which is purportedly 7 m (23 ft) long with an estimated mass of 2,000 kg (4,400 lb).[1]

The following table below lists the 15 largest extant reptile species ranked according to their average mass range, with maximum reported/reliable/estimated mass also being provided.

Overall

| Rank | Species | Image | Mass range [kg] | Maximum mass [kg] | Maximum length [m] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Saltwater crocodile | 400 – 1,300[2][4] | 2,000[2] | 7[5] | |

| 2 | Nile crocodile[6][7][8][9] | 250 – 900[10][11] | 1,090[6] | 6.5[6] | |

| 3 | American crocodile | 150 – 600[12] | 1,283[13] | 7[14] | |

| 4 | Orinoco crocodile | 200 – 700[15][16] | 1,100 | 7[17] | |

| 5 | Black caiman | 300 – 500[18] | 1,100[19][20] | 6[21][22] | |

| 6 | American alligator | 200 – 500[23][24] | 1,000[1] | 5.8 | |

| 7 | Gharial | 160 – 680[25][26] | 1,000[27] | 7[28] | |

| 8 | Leatherback sea turtle | 200 – 500[29][30] | 961.1[31] | 3 | |

| 9 | False gharial | 100 – 590[32][33][34] | 800[35] | 7[36] 7 | |

| 10 | Mugger crocodile | 160 – 450[37] | 700[38] | 5.63 | |

| 11 | Slender-snouted crocodile | 125 - 325[39][40][41] | 667[42] | 4.5[43] | |

| 12 | Loggerhead sea turtle | 100 – 350[44][45][46] | 545[47] | 2.1[47] | |

| 13 | Green sea turtle | 100–320 | 500[48][49] | 1.8 | |

| 14 | Galapagos tortoise | 150 – 300[50][51] | 417[52] | 1.8 | |

| 15 | Aldabra giant tortoise | 132 – 250[53] | 360[1] | 1.5 |

Lizards and snakes (Squamata)

- The most massive living member of this highly diverse reptilian order is the green anaconda (Eunectes murinus) of the neotropical riverways. These may exceed 6 m (20 ft) and 200 kg (440 lb), although such reports are not fully verified.[54] Rumors of larger anacondas also persist.[55] The reticulated python (Malayopython reticulatus) of Southeast Asia is longer but more slender, and has been reported to measure as much as 8 m (26 ft) in length and weigh up to 168 kg (370 lb).[1][56][57] The Burmese python, a south-east Asian species is known to reach up to 6 m (20 ft) and weigh as much as 150 kg (330 lb) and is generally among the three heaviest species of snakes.[58] Several other species of python can reach or exceed 6 m (20 ft) in length and 90 kg (200 lb) in weight. The fossil of the largest snake ever, the extinct boa Titanoboa were found in coal mines in Colombia. This snake was estimated to reach a length of 12.8 m (42 ft) and weighed about 1,135 kg (2,502 lb).[59]

- Among the Pseustes sulphureus) can reach lengths of 3 m (10 ft), but they are relatively slender and generally do not exceed 5 kg (11 lb) in weight.

- The longest venomous snake is the venomous snake in the world is possibly the African black mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis), which can grow up to 4.5 m (15 ft). Among the genus Naja, the longest member arguably may be the forest cobra (Naja melanoleuca), which can reportedly grow up to 3.2 m (10.5 ft). The King brown snake, reaching lengths of up to 3.3 m (11 ft) and weights of 8 kg (18 lb) or more, is the largest venomous snake in Australia.[64] The Yellow sea snake (Hydrophis spiralis) is the largest of the sea snakes growing up to a length of 3 m (10 ft). Few other elapids can reach or exceed 3 m (10 ft) in length and 9 kg (20 lb) in weight.[65][66]

- The Central American bushmaster (Lachesis stenophrys), with a maximum length in the range of 3 to 4 m (10 to 13 ft), with the former being considered as the third-longest venomous snake in the world.[70]

- The largest of the monitor lizards (and the largest extant lizard in genera) is the Crocodile monitor (Varanus salvadorii) is probably the longest living lizard, known to grow as much as 3.23 m (10.6 ft), with reported lengths of up to 4.8 m (16 ft) and weights of up to 90 kg (200 lb).[71][72][73] The Asian water monitor is also one of the largest lizards in the world, with sizes of up to 3.21 m (10.5 ft) and reported weights of up to 90 kg (200 lb).[74] Few other species (such as perentie and nile monitor) can reach or possibly exceed 2.4 m (8 ft) in length and 20 kg (44 lb) in weight. The prehistoric Australian megalania (Varanus priscus), which may have existed up to 40,000 years ago, is the largest terrestrial lizard known to exist, but the lack of a complete skeleton has resulted in a wide range of size estimates. Molnar's 2004 assessment resulted in an average weight of 320 kg (710 lb) and length of 4.5 m (15 ft), and a maximum of 1,940 kg (4,280 lb) at 7 m (23 ft) in length, which is toward the high end of the early estimates.[75]

- Galapagos Islands after the Galapagos land iguana, not including turtles reaching a maximum total length of 1.4 m (4.59 ft), a SVL of from 12 till 56 cm (from 4.72 till 22 in)[83][84] and a mass of from 1 to 12 kg (2.2 to 26.5 lb)[85]depending on islands.

- The largest extant gecko is the Kawekaweau (Hoplodactylus delcourti) of New Zealand, which grew to a length of 580 mm (23 in).[87]

- By far the largest-ever members of this order were the giant Hainosaurus, Mosasaurus, and Tylosaurus), which grew to around 17 m (56 ft) and were projected to weigh up to 20 t (44,000 lb).[88]

Tuataras (Sphenodontia)

The larger of the two

Ichthyosaurs (Ichthyosauria)

Some of these marine reptiles were comparable in size to modern cetaceans. Until 2024, the largest

Pantestudines

Turtles and tortoises (Testudines)

- The largest extant turtle is the leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), reaching a maximum total length of 3 m (10 ft) and a weight of 961 kg (2,119 lb).[1][97] The second-largest extant testudine is the Loggerhead sea turtle. It tends to weight slightly more average weight than the green sea turtle, and reaches more massive top sizes. The Loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) reaches a maximum size of 2.1 m (7 ft) and weight of 545 kg (1,202 lb), while the Green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) reaches a maximum weight in the range of 395 to 500 kg (871 to 1,102 lb).[47] The Flatback sea turtle (Natator depressus) may reach a weight of up to 350 kg (770 lb).[98] Other species of Sea turtles are small-medium in size, but are still considered as large-sized for a typical turtle.

- The largest extant freshwater turtle is possibly the North American critically endangered turtles have been reported to grow to massive sizes. The Asian narrow-headed softshell turtle (Chitra chitra), at up to 254 kg (560 lb), and the Indian narrow-headed softshell turtle (Chitra indica), at up to 202 kg (445 lb), are also contenders for the title of the largest extant freshwater turtle.[102][103]

- The Galápagos tortoise (Chelonoidis nigra) and the Aldabra giant tortoise (Aldabrachelys gigantea) are considered the largest truly terrestrial reptiles alive today.[1] While the Aldabra tortoise averages larger at 205 kg (452 lb), the more variable-sized Galapagos tortoise can reach a greater maximum size of 400 kg (880 lb) and 1.85 m (6.1 ft) in total length.[104][105] The Aldabra giant tortoise has a maximum recorded weight of 363 kg (800 lb). The African spurred tortoise (Centrochelys sulcata) is the third-largest extant tortoise (and the largest mainland tortoise) in the world. The large adults of this species may reach 1 m (3.3 ft) in length and weigh more than 100 kg (220 lb).[106] Other relatively large-sized tortoises include the Yellow-footed tortoise (Chelonoidis denticulatus) and Leopard tortoise (Stigmochelys pardelis), at up to 54 kg (119 lb), and the Asian forest tortoise (Manouria emys), at up to 37 kg (82 lb) or more, can be rather large as well.[107][108] The tortoise Megalochelys, of the Pleistocene epoch from what is now Pakistan and India, was even larger, at nearly 2.7 m (9 ft) in shell length[109] and 0.8–1.0 t (1,800–2,200 lb).[110]

- The largest of side-necked turtles (Pleurodira) is the Arrau turtle (Podocnemis expansa). Its carapace length is up to 1.07 m (3.5 ft) and adults can reach up to 90 kg (200 lb) in weight.[111] There are also reports of these turtles weighing up to 118 kg (260 lb).[112] The Mata mata (Chelus fimbriata) is another large species of side-necked turtle with a carapace length of up to 1 m (3.3 ft) and weight of more than 21 kg (46 lb).

- There are many extinct turtles that vie for the title of the largest ever.Archelon ischyros, a sea turtle, which reached a length of 5 m (16 ft) and a weight of 2,200 kg (4,900 lb).[114]

Meiolaniformes

A terrestrial relative of turtles survived until about 2,000 years ago, the Australasian Meiolania at about 2.6 m (8 ft 6 in) long and a weight of over 1 t (2,200 lb).[1] Later research suggests the maximum length possibly over 3 m (9.8 ft).[115]

Plesiosaurs (Plesiosauria)

Crocodilians (Crocodilia)

- Some species of critically endangered Orinoco crocodile (Crocodylus intermedius) can reach lengths of 6 m (20 ft) or more. The largest known specimen among the living crocodilians was an Orinoco crocodile with a length of 6.78 m (22.2 ft).[2] One of the largest known Saltwater crocodile measured 6.2 m (20.3 ft) and was shot in Papua New Guinea.[2] A 6.17 m (20.2 ft) long individual was captured alive in Mindanao in 2011.[3] The largest confirmed Saltwater crocodile on record was 6.32 m (20.7 ft) long, and weighed about 1,360 kg (3,000 lb).[118] In 2006, Guinness World Records accepted claims of a 7-metre (23 ft), 2,000-kilogram (4,400 lb) male saltwater crocodile, living within Bhitarkanika National Park.[119] Due to the difficulty of trapping and measuring a large living crocodile, the accuracy of these dimensions is yet to be verified. These observations and estimations have been made by park officials over the course of ten years, from 2006 to 2016, however, regardless of the skill of the observers it cannot be compared to a verified tape measurement, especially considering the uncertainty inherent in visual size estimation in the wild.[120] The largest Nile crocodile accurately measured, shot near Mwanza, Tanzania, measured 6.45 m (21.2 ft) and weighed about 1,043–1,089 kg (2,300–2,400 lb).[118] Another large Nile crocodile specimen was purported to be a man-eater from Burundi named Gustave; it was thought to have been more than 6.1 m (20 ft) long. The American crocodile is also one of the largest crocodile species, with large males in the southern part of their range reported to approach 6.1 m (20 ft) in size. Based on projections from various skulls, the largest males may have reached 6–7 m (20–23 ft) in length, and their predicted mass reached up to 1,283 kg (2,829 lb).[121] Other crocodiles can also grow to large sizes, such the Mugger crocodile, which typically reaches an average maximum length of 4–5 m (13–16 ft), and has a maximum reported length of 5.63 m (18.5 ft). The extinct Crocodylus thorbjarnarsoni was the largest species in its genus, growing up to 7.56 m (24.8 ft) in length.[122] The largest true crocodile ever existed is Euthecodon which estimated to have reached 6.4–8.6 m (21–28 ft) or even 10 m (33 ft) long.[123][124]

- A 6.55 m (21.5 ft) long Ghaghara River in Faizabad in August 1920.[125] Male gharials may grow up to a length of 7 m (23 ft).[126][28] The heaviest recorded gharial was a male measuring 6.25 m (20.5 ft) in total length and weighing 977 kg (2,154 lb).[127] The False gharial is also a large crocodilian with males reaching 5 m (16 ft) in length, weighing up to at least 590 kg (1,300 lb).[34] The largest gavialid to ever exist was the extinct Rhamphosuchus from the Miocene of Asia. It was originally thought to be 18 m (59 ft) long and more than 20 t (44,000 lb) in weight but later estimations suggest 11 m (36 ft) and 2–3 t (4,400–6,600 lb). Based on its fossils, the latter species was less massive and heavy than the other giant crocodilians, weighing an estimated 3 t (6,600 lb).[128][129]

- The largest member of the family Alligatoridae is the Black caiman (Melanosuchus niger) with the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) sometimes growing to similar lengths. Black caimans can reach more than 5 m (16 ft) in length and weigh up to 750 kg (1,650 lb).[130] American alligators can be almost as large, with males reaching 4.6 m (15 ft) in length and weighing over 500 kg (1,100 lb).[131] Unverified reports suggest lengths of up to 6 m (20 ft) for the black caiman and 5.84 m (19.2 ft) for the American alligator, reaching weights of over 1,000 kg (2,200 lb), but such lengths are probably exaggerated.

- The giant prehistoric caiman, Sarcosuchus imperator of the early Cretaceous was found in the Sahara desert and could measure up to 9–9.5 m (30–31 ft) and weigh an estimated 3.5 t (7,700 lb).[135]

Pterosaurs (Pterosauria)

A Mesozoic reptile is believed to have been the largest flying animal that ever existed: the pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus northropi, from North America during the late Cretaceous. This species is believed to have weighed up to 126 kg (278 lb), measured 7.9 m (26 ft) in total length (including a neck length of over 3 m (9.8 ft)) and measured up to 10–12 m (33–39 ft) across the wings.[136][137] Another possible contender for the largest pterosaur is Hatzegopteryx, which is estimated to have had an 11–12 m (36–39 ft) wingspan.[137][136] An unnamed Mongolian pterodactyloid pterosaur[138] and Arambourgiania from Jordan could reach a wingspan of nearly 10 m (33 ft).[139]

Non-avian dinosaurs (Dinosauria)

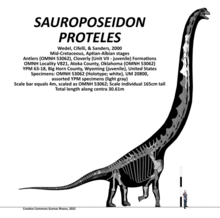

- The main contender for the largest The Guinness Book of Records as the longest dinosaur at 48 m (157 ft) but this animal is known only from fossil tracks.[142][143] The better studied Supersaurus was possibly as long as over 40 m (130 ft).[144] One of the heaviest sauropods was Argentinosaurus at 35 m (115 ft) in length and 65–75 t (143,000–165,000 lb)[141][145] or even 100 t (220,000 lb) in body mass.[141] The tallest sauropods were probably Xinjiangtitan and Sauroposeidon with total height of 17 m (56 ft) and 16.5–18 m (54–59 ft), respectively.[141][146][147]

- The largest non-avian theropod was Tyrannosaurus Rex, estimated at 12.1–12.2 m (40–40 ft) in length and around 8–10.6 t (18,000–23,000 lb) in weight.[148][149]

- The largest

- The largest ceratopsian was Triceratops, reaching 8–9 m (26–30 ft) in length and 5–9 t (11,000–20,000 lb) in weight.[152][153][154]

- The largest ornithopod was the Late Cretaceous Shantungosaurus at up to 23 t (51,000 lb),[155][156] and 16.6 m (54 ft) in length.[155]

References

- ^ ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ^ a b c d e Whitaker, R.; Whitaker, N. (2008). "Who's got the biggest?" (PDF). Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter. 27 (4): 26–30.

- ^ a b Britton, A. R. C.; Whitaker, R.; Whitaker, N. (2012). "Here be a Dragon: Exceptional Size in Saltwater Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) from the Philippines". Herpetological Review. 43 (4): 541–546.

- ^ Ogamba, E.N. and Abowei, JFN (July 2012). Some Aquatic Reptiles in Culture Fisheries Management. International Journal of Fishes and Aquatic Sciences. pp. 5–15.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - JSTOR 1564770.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9

- ISBN 978-0-7153-5272-4.

- ^ Brazaitis, P. (1989). The forensic identification of crocodilian hides and products. In: Crocodiles: Their Ecology, Management, and Conservation. IUCN Special Publication of Crocodile Specialist Groups of the Species Survival Commission. pp. 17–43.

- ^ Graham, A. D. (1968). The Lake Rudolf Crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus Laurenti) Population. Masters of Science Thesis, The University of East Africa.

- ^ Stefanie B. Ganswindt (October 2012). Non-invasive assessment of adrenocortical function in captive Nile crocodiles (Crocodylus niloticus) and its relation to housing conditions (PDF). University of Pretoria.

- ^ "Nile Crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus)". Archived from the original on 2018-09-23. Retrieved 2013-12-14.

- ^ "TERRAPENE CAROLINA TRIUNGUIS (Three-toed Box." Herpetological Review, 41(4). ORNATA, T. O. p. 489.

- ^ FESTIVA, AMEIVA and Ameivafestiva (December 2010). Herpetological Review. p. 490.

- ^ Jake Fishman. "ADW: Crocodylus acutus: INFORMATION". Animal Diversity Web.

- ^ Orinoco crocodile videos, photos and facts – Crocodylus intermedius Archived 2017-09-06 at archive.today. ARKive

- ^ Zoo, Gladys Porter. "Critically Endangered Orinoco Crocodiles Coming to Gladys Porter Zoo". www.prnewswire.com (Press release).

- ^ WAZA. "Orinoco Crocodile". Archived from the original on 2013-11-10. Retrieved 2013-05-02.

- ^ French Guiana. kwata.net (2003).

- ISBN 978-1-4214-3338-7.

- ISBN 9780199688418.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Black Caiman, Black Caiman Skull. Dinosaurcorporation.com. Retrieved on 2012-08-23.

- ^ Crocodilian Species – Black Caiman (Melanosucus niger). Crocodilian.com. Retrieved on 2012-08-23.

- ISSN 1843-5270.

- ^ "American Alligator". 25 April 2016.

- ^ Stevenson, C.; Whitaker, R. (2010). "Gharial Gavialis gangeticus" (PDF). In Manolis, S. C.; Stevenson, C. (eds.). Crocodiles. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan (Third ed.). Darwin: Crocodile Specialist Group. pp. 139–143.

- ^ "Gavial". www.aquaticcommunity.com.

- ^ Gavials (Gharials), Gavial (Gharial) Pictures, Gavial (Gharial) Facts. Animals.nationalgeographic.com

- ^ a b "Gharial". Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved September 26, 2011.

- ^ Leatherback Sea Turtle. euroturtle.org Archived April 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "AquaFacts". Archived from the original on 2011-09-07. Retrieved 2013-12-14.

- ^ "Largest turtle/chelonian". Guinness World Records.

- ^ http://www.zoonegaramalaysia.my/RPFalseGharial.pdf Archived 2018-01-27 at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]

- PMID 22431965.

- ^ PMID 28942308.

- ^ "False gharial – Tommy". Ferme aux crocodiles.

- ^ Kyle Shaney, Bruce Shwedick, Boyd Simpson and Colin Stevenson. Tomistoma (Tomistoma schlegelii) (PDF). Crocodile Specialist Group (IUCN).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Marsh Crocodile". www.wii.gov.in.

- .

- ^ "African Slender-Snouted Crocodile – The Maryland Zoo in Baltimore". The Maryland Zoo in Baltimore.

- ^ "Slender-Snouted Crocodile – San Diego Zoo Animals".

- ^ "African Slender-snouted Crocodile". The Maryland Zoo.

- ISBN 9780429844232.

- ^ J Milan, R Hedegaard (2010). Interspecific variation in tracks and trackways from extant crocodylians. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. pp. 15–29.

- ^ "Loggerhead Turtle | Sea Turtles | Species | WWF". World Wildlife Fund.

- ^ "ECOS: Species Profile". ecos.fws.gov.

- ^ "Loggerhead sea turtle, facts and photos". Animals. 11 April 2010. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Largest hardshell sea turtle". Guinness World Records. 6 March 2018.

- S2CID 20253025.

- PMID 3558205.

- ^ ADW: Geochelone nigra: Information. Animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu

- PMID 27336221.

- ^ "Largest tortoise (specimen)". Guinness World Records.

- ^ "Aldabra tortoise". 25 April 2016.

- ^ Barker, David G.; Barten, Stephen L.; Ehrsam, Jonas P.; Daddono, Louis (2012). "The Corrected Lengths of Two Well-known Giant Pythons and the Establishment of a new Maximum Length Record for Burmese Pythons, Python bivittatus" (PDF). Bulletin Chicago Herpetology Society. 47 (1): 1–6. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ^ Green Anacondas, Green Anaconda Pictures, Green Anaconda Facts. Animals.nationalgeographic.com

- ^ Cotswold Wildlife Park and Gardens | Reticulated python. Cotswoldwildlifepark.co.uk

- ^ "Largest albino snake in captivity". Guinness World Records. 7 December 2012.

- ^ "Burmese Python | National Geographic". Animals. 10 September 2010. Archived from the original on February 28, 2021.

- S2CID 4381423.

- ^ "Keeled Rat Snake – Ptyas carinata – Not Dangerous | Thailand Snakes". 20 January 2013.

- ^ Auliya, M. (2010). Conservation Status and Impact of Trade on the Oriental Rat Snake Ptyas mucosa in Java, Indonesia. TRAFFIC Southeast Asia.

- ^ Das, I. (2015). A field guide to the reptiles of South-East Asia. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- ^ Spilotes pullatus (Tiger Rat Snake or Clibo) (PDF). The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago.

- ^ Beatson, Cecilie (25 November 2018). "Mulga Snake". Animal Species. Australian Museum. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ "Oxyuranus scutellatus – General Details". Clinical Toxinology Resource. University of Adelaide. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ Australian Broadcasting Corporation (3 October 2014). "Massive red-bellied black snake surprises Newcastle wrangler called in to remove it". ABC News. Archived from the original on 10 February 2019. Retrieved 4 Dec 2018.

- ^ Gaboon Viper, Bitis gabonica Archived 2014-10-06 at the Wayback Machine. California Academy of Sciences

- ^ ISBN 0-520-01775-7.

- ^ Monster Basiliscus Weighed – 20 lb Rattlesnake. SnakeBytesTV. April 1, 2020. Retrieved 2022-06-27.

- ISBN 0-8069-6460-X.

- ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ^ "Longest lizard". Guinness World Records.

- ^ Wojtasek, Gregory. "Varanus salvadorii (Crocodile Monitor)". Animal Diversity Web.

- ^ "The Largest Monitor Lizards by Paleonerd01 on DeviantArt". www.deviantart.com. 18 August 2019.

- ISBN 978-0-253-34366-6.

- ^ Rivas, J.A. (2008). Pers. comm.

- ^ ISBN 1882770676.

- ^ Dorge, Ray (1996). "A Tour of the Grand Cayman Blue Iguana Captive-Breeding Facility". Reptiles: Guide to Keeping Reptiles and Amphibians. 4 (9): 32–42.

- ^ a b c "The 10 Largest Lizards in The World". A-z-animals.com. 18 August 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^

Rogers, Barbara (1990), Galapagos, New York: Mallard Press, p. 144, ISBN 978-0-7924-5192-1

- ^ Rosenthal, Ellen (1997), "Days and nights of the iguana: in the Galapagos, a devoted pair work to save land iguanas", Animals

- ^ a b Cruz M. Márquez B. (June 2010). "Estado poblacional de las iguanas terrestres (Conolophus subcristatus, C. pallidusy C.marthae: Squamata, Iguanidae), Islas Galápagos". Boletín Técnico, Serie Zoológica (in Spanish). Vol. 9. Sangolquí, Équateur: ESPE. pp. 19–37..

- .

- S2CID 205780374.

- ^ Endangered animals of the world pp. 48

- ^ Allison Ballance and Rod Morris, "Island Magic; wildlife of the south seas", David Bateman publishing, 2003

- ISBN 978-0-908812-52-3.

- ^ Science & Nature – Sea Monsters – Fact File: Giant Mosasaur. BBC (2005-08-26)

- ^ "Triassic Giant". Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2022.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2022.

- S2CID 130274656.

- ^ "Researchers have found a 205-million-year-old jawbone from one of the largest animals that ever lived". Newsweek. 9 April 2018. Archived from the original on 21 September 2022.

- from the original on 27 February 2022.

- PMID 38630678.

- ^ https://www.newscientist.com/article/2317948-ichthyosaur-tooth-from-the-swiss-alps-is-largest-ever-discovered/

- ^ "Largest turtle/chelonian". Guinness World Records.

- ISBN 978-0-08-096481-2.

- ^ Lukas I. Alpert Sacred century-old turtle pulled from Vietnam lake in effort to save its life. New York Daily News (2011-04-04)

- ^ Seth Mydans. "How to Survive in Cambodia: For a Turtle, Beneath Sand," New York Times (2007-05-18).

- ^ "Largest freshwater turtle (living)". Guinness World Records. 27 October 2016.

- ^ "Asian Narrow-headed Softshell Turtle". EDGE of Existence.

- ^ "Narrow-headed Softshell Turtle". EDGE of Existence.

- ^ Ebersbach, V.K. (2001). Zur Biologie und Haltung der Aldabra-Riesenschildkröte (Geochelone gigantea) und der Galapagos-Riesenschildkröte (Geochelone elephantopus) in menschlicher Obhut unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Fortpflanzun (PhD thesis). Hannover: Tierärztliche Hochschule. [1].

- ISBN 0-934394-05-9

- ^ Pizzi, R and Goodman, G and Gunn-Moore, D and Meredith, A and Keeble, Emma (2005). Pieris japonica intoxication in an African spurred tortoise (Geochelone sulcata). London: The Association. pp. 487–488.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baker, Hillary H.; Grubb, Jordan N. "Psammobates pardalis (Leopard Tortoise)". Animal Diversity Web.

- ISBN 978-3-030-25865-8.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - .

- doi:10.1017/S2475262200009515. Archived from the original(PDF) on 20 September 2022.

- INPA. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ Cesar L. Barrio-Amoros, Ínigo Narbaiza (2008). Turtles of the Venezuelan Estado Amazonas (PDF). Radiata 17(1). pp. 2–19.

- PMID 32095528.

- PMID 32650718.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - from the original on 18 June 2022.

- S2CID 181725020.

- ISSN 1502-5322. Archived from the original(PDF) on 1 March 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ^ Mishra, Braja Kishore (14 June 2006). "World's Largest Reptile Found in India". ohmynews.com. Archived from the original on 8 January 2008.

- ^ Bayliss, P. (1987). Survey methods and monitoring within crocodile management programmes. Surrey Beatty & Sons, Chipping Norton, pages 157–175

- ^ Juan Gabriel Abarca, Charles R. Knapp (December 2010). Herpetological Review. p. 490.

- S2CID 85103427.

- ISBN 0-231-11870-8.

- ^ "Крупнейшие крокодиломорфы". vk.com (in Russian). Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- ^ Pitman, C. R. S. (1925). "The length attained by and the habits of the Gharial (G. gangeticus)". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 30 (3): 703.

- ^ Whitaker, R.; Basu, D. (1982). "The Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus): A review". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 79 (3): 531–548.

- PMID 32435543.

- ISBN 0-405-05742-3.

- ^ "Prehistoric Crocodile Evolution". ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022.

- ISBN 978-1-4214-3338-7.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - PMID 2873921.

- ^ Schwimmer, David R. (2002).

- S2CID 85950121.

- ISBN 0-253-34087-X.

- PMID 33791523.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ a b Mark P. Witton, David M. Martill and Robert F. Loveridge, 2010, "Clipping the Wings of Giant Pterosaurs: Comments on Wingspan Estimations and Diversity", Acta Geoscientica Sinica, 31 Supp.1: 79–81

- ^ PMID 18509539.

- ^ "Ancient Winged Terror Was One of the Largest Animals to Fly". 31 October 2017. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019.

- S2CID 134424023.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Carpenter, K. (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus". In Foster, J. R. and Lucas, S. G., eds., 2006, Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 36: 131–138.

- ^ OCLC 1125972915.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ISBN 9780851129785.

- ISBN 9780553583755.

- ^ Curtice, Brian (2021). "New Dry Mesa Dinosaur Quarry Supersaurus vivianae (Jensen 1985) axial elements provide additional insight into its phylogenetic relationships and size, suggesting an animal that exceeded 39 meters in length" (PDF).

- S2CID 210840060.

- S2CID 59141243. Archived from the original(PDF) on June 26, 2020.

- ISBN 9780553587128.

- S2CID 86025320.

- S2CID 85702490.

- ^ Vickaryous, M.K., Maryanska, T., & Weishampel, D.B. 2004. Ankylosauria. In: Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., & Osmólska, H. (Eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd edition). Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 363–392.

- S2CID 84505681.

- .

- S2CID 53446536.

- ^ Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012). Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages (PDF).

Winter 2011 Appendix

- ^ S2CID 119700784.

- ^ Morris, William J. (1981). "A new species of hadrosaurian dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of Baja California: ?Lambeosaurus laticaudus". Journal of Paleontology. 55 (2): 453–462.