Mind-blindness

Mind-blindness, mindblindness or mind blindness is a theory initially proposed in 1990 that claims that all autistic people have a lack or developmental delay of theory of mind (ToM), meaning they are unable to attribute mental states to others.[1][2][3] According to the theory, a lack of ToM is considered equivalent to a lack of both cognitive and affective empathy.[4] In the context of the theory, mind-blindness implies being unable to predict behavior and attribute mental states including beliefs, desires, emotions, or intentions of other people.[5] The mind-blindness theory asserts that children who delay in this development will often develop autism.[4][6]

One of the main proponents of mind-blindness was

Theory of mind

Mind-blindness is defined as a state where the ToM has not been developed in an individual.[1] According to the theory, neurotypical people can make automatic interpretations of events taking into consideration the mental states of people, their desires, and beliefs. Individuals lacking ToM would therefore perceive the world in a confusing and frightening manner, leading to a social withdrawal.[1] The theory was based on the assumption that biology is linked to autistic behavior, so it was expected that a delayed development or lack of ToM would lead to additional psychiatric complications. Research into a model with more than two categories was also considered.[1]

Mind-blindness, a lack of ToM, was later theorised to be equivalent to a lack of empathy,[4] although research published a year later suggests there is considerable overlap but not complete equivalence.[17] It was empirically demonstrated that processing of complex cognitive emotions is more difficult than processing simpler emotions. In addition, evidence existed at the time that autism was not correlated with the failure of social bonding and attachment in childhood. This was interpreted to suggest that emotion is a component of social cognition that is separable from mentalizing.[3]

Biological basis

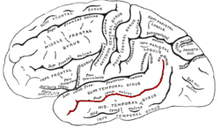

Since the frontal lobe is associated with executive function, it was predicted that the frontal lobe plays an important role in ToM; that executive function and ToM share the same functional regions in the brain.[18] Damage to the frontal lobe is known to affect ToM,[19][20] partially confirming this hypothesis. From a 2000 study, it was found that a neural network that comprised the medial prefrontal cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex, the circumscribed region of the anterior paracingulate cortex and the superior temporal sulcus, is crucial for the normal functioning of ToM and self monitoring.[5][21] Although there is a possibility that ToM and mind-blindness could explain executive function deficits, it was argued that autism is not identified with the failure of executive function alone.[22] It has also been shown that the right temporo-parietal junction behaves differently in those with autism,[23] and the middle cingulate cortex is less active in autistic people during mentalization.[24]

History and relationship to autism

Mind-blindness of autistic people relative to non-autistic people

In an attempt to empirically explain the tendency of autistic people to avoid eye contact, a hypothesis was proposed in 1995 that autistic children fail to "read" the eyes of others.[2] This hypothesis was tested with participant performance on false-belief tasks and detecting gaze shifts.[25] In the moral blindness hypothesis study, some evidence existed to support this hypothesis. At the time there was insufficient evidence to support a generalization to explain facial processing difficulties and affective sensitivity, common characteristics of autism, with this hypothesis. In 2001, it was suggested that the mind-blindness hypothesis may explain more severe symptoms of autism, including social withdrawal and social skill deficiencies.[3] With good robustness, it was found that a lower performance on mentalization tasks correlates with autism, suggesting mentalization theory as an effective explanatory model of autism, especially for social skill deficiencies. However, the generally unclear physiological basis of mentalization at the time limited a broader understating of the correlation.[3]

In the 1996 book Theories of Mind,[26]: 258 Peter Carruthers argues in support of the mind-blindness hypothesis in spite of inconclusive evidence for its generalisation. Recognising the hypothesis has lost popularity, Carruthers argues this is mainly due to the disregard of its proponents to consider the perspectives of autistic people.[26]: 259 The latter view is shared by David Smukler in his 2005 analysis of the history of the ToM in autism research.[11]

The assumption that autism is a homogenous condition underpinned by a ToM deficit, genetics, neurological abnormalities, or a 'failure of understanding' as implied by the mind-blindness hypothesis was questioned shortly after its publication.[10] This contrasts with autism as heterogeneous.[11] There is now a large pool of strong evidence supporting the heterogeneity of autism,[27][28][29] and general scientific consensus accepts this as contrary to the original mind-blindness hypothesis, although there has existed some disagreement that heterogeneity is incompatible with alternative mind-blindness definitions.[11]

An author of the original mind-blindness hypothesis,

Mind-blindness of non-autistic people relative to autistic people

The

See also

Citations

- ^ .

- ^ S2CID 34341464.

- ^ PMID 11754830.

- ^ S2CID 2822141.

- ^ S2CID 14873867.

- ^ S2CID 1440395.

- .

- S2CID 30738704.

- PMID 31938672.

- ^ S2CID 143801835.

- ^ PMID 15628930.

- S2CID 151487088.

- PMID 30420503.

- PMID 27752054.

- S2CID 248345497.

- PMID 23880881.

- S2CID 13999363.

- S2CID 11112882.

- PMID 14998913.

- S2CID 207724498.

- S2CID 7053366.

- ISBN 978-0-521-55916-4.

- S2CID 14782731.

- PMID 18255038.

- S2CID 25792636.

- ^ ISBN 9780521551106.

- S2CID 10216391.

- PMID 24198778.

- S2CID 203059811.

- S2CID 44330420.

- )

- ^ S2CID 54047060.

- ^ "Double empathy, explained". Spectrum. Simons Foundation. 2021-07-22. Retrieved 2022-02-13.

- ISSN 0021-843X.

Further reading

- Baron-Cohen, Simon (June 15, 1996). "First lessons in mind reading". Times Higher Education Supplement. No. 1180. p. 18.

- Smukler, David (February 2005). "Unauthorized Minds: How 'Theory of Mind' Theory Misrepresents Autism". Mental Retardation. 43 (1): 11–24. PMID 15628930.