Narwhal

| Narwhal | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

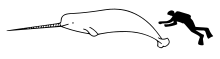

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Monodontidae |

| Genus: | Monodon Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Species: | M. monoceros

|

| Binomial name | |

| Monodon monoceros | |

| |

| Distribution of narwhal populations | |

The narwhal (Monodon monoceros), is a species of

The narwhal inhabits

There are estimated to be 170,000 living narwhals, and the species is listed as

Taxonomy

The narwhal was one of many species originally described by Carl Linnaeus in his 1758 Systema Naturae.[5] An early 1555 drawing by Olaus Magnus depicts a fish-like creature with a horn on its forehead. He later assigned it to "Monocerote".[6] Its name comes from the Old Norse word nár, meaning "corpse," which possibly refers to the animal's gray, mottled skin[7] and its habit of remaining motionless at the water's surface, a behavior known as "logging" that usually happens in the summer.[8] The scientific name, Monodon monoceros, is derived from Greek: "single-tooth single-horn".[9]

The narwhal is most closely related to the

Although the narwhal and beluga are classified as separate genera, there is some evidence that they may, very rarely,

Evolution

Genetic evidence suggests that within the

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Description

The narwhal is a medium-sized whale, with a body length of 3.0 to 5.5 m (9.8 to 18.0 ft), excluding the tusk.[20][21] Males average 4.1 m (13 ft) in length, while females average 3.5 m (11 ft). Adults typically range between 800 to 1,600 kg (1,800 to 3,500 lb), with males outweighing their female counterparts.[20] Male narwhals attain sexual maturity at 11 to 13 years of age, reaching a length of 3.9 m (13 ft). Females become sexually mature at a younger age, between 5 and 8 years old, when they are about 3.4 metres (11 ft) long.[20]

The

Compared with most other marine mammals, the narwhal has a higher amount of

Tusk

The most conspicuous characteristic of the male narwhal is a single long tusk, which is a canine tooth[26] that projects from the left side of the upper jaw.[27] The tusk grows throughout the animal's life, reaching an average of 1.5 to 2.5 m (4.9 to 8.2 ft).[28][29] Tusks can sometimes reach lengths of up 3 m (9.8 ft).[30] It is hollow and weighs up to 7.45 kg (16.4 lb). Some males may grow two tusks, occurring when the right canine also protrudes through the lip.[31] Females rarely grow tusks: when they do, the tusks are typically smaller than those of males, with less noticeable spirals.[32][33]

The purpose of the narwhal tusk is debated. Some biologists suggest that narwhals use their tusks in fights, while others argue that their tusks may be of use in breaking sea ice or in finding food. Tusks are universally acknowledged to be

Vestigial teeth

The narwhal has several small vestigial teeth that reside in open tooth sockets which are situated in the upper jaw. These teeth, which differ in form and composition, encircle the exposed tooth sockets laterally, posteriorly, and ventrally.[26][41] The varied morphology and anatomy of small teeth indicate a path of evolutionary obsolescence.[26]

Distribution

The narwhal is found predominantly in the Atlantic and Russian areas of the

Migration

Narwhals exhibit seasonal migrations, with a high fidelity of return to preferred, ice-free summering grounds, usually in shallow waters. In summer months, they move closer to coasts, often in pods of 10–100. In the winter, they move to offshore, deeper waters under thick pack ice, surfacing in narrow fissures in the sea ice, or in wider fractures known as leads.[45] As spring comes, these leads open up into channels and the narwhals return to the coastal bays.[46] Narwhals in the Baffin Bay typically travel further north, to northern Canada and Greenland, between June and September. After this period, they move south to the Davis Strait, a journey that spans around 1,700 kilometres (1,100 mi), and stay there until April.[44] Narwhals from Canada and West Greenland winter regularly visit the pack ice of the Davis Strait and Baffin Bay along the continental slope with less than 5% open water and high densities of Greenland halibut.[47]

Behaviour and ecology

Narwhals normally congregate in groups of five to ten—and sometimes up to twenty—individuals. Groups may be "nurseries" with only females and young, or can contain only post-dispersal juveniles or adult males ("bulls"), but mixed groups can occur at any time of year.[20] In the summer, several groups come together, forming larger aggregations which can contain from 500 to over 1,000 individuals.[20] Bull narwhals have been observed rubbing each other's tusks, a display known as "tusking".[36][48]

When in their wintering waters, narwhals make some of the deepest dives recorded for a marine mammal, diving to at least 800 m (2,620 ft) over 15 times a day, with many dives reaching 1,500 m (4,920 ft). Dives to these depths last around 25 minutes.[49] Dive times can also vary in depth, based on local variation between environments, as well as seasonality. For example, in the Baffin Bay wintering grounds, they tend to dive deep within the precipitous coasts, typically south of Baffin Bay. This suggests differences in habitat structure, prey availability, or genetic adaptations between subpopulations. In the northern wintering grounds, narwhals do not dive as deep as the southern population, in spite of the greater water depths in these areas. This is mainly attributed to prey being concentrated nearer the surface, which causes narwhals to subsequently alter their foraging strategies.[49]

Diet

Compared with other marine mammals, narwhals have a relatively restricted and specialized diet.

In

Breeding

Female narwhals start bearing calves when six to eight years old.[8] Adults mate from March to May when they are in the offshore pack ice. After a gestation of 15 months, females give birth to calves between July and August.[53] As with most marine mammals, only a single young is born, averaging 1.5 m (4.9 ft) in length. At birth, calves are white or light grey in colour.[54] The birth interval is typically between two and three years.[55] During summer population counts along different coastal inlets of Baffin Island, calf numbers varied from 0.05% to 5% of the total numbering from 10,000 to 35,000 narwhals, suggesting that higher calf counts may reflect calving and nursery habitats in favourable inlets.[56]

Newborn calves begin their lives with a thin layer of

In a 2024 study, scientists concluded that 5 species of Odontoceti evolved menopause to acquire higher overall longevity. Their reproductive lives on the other hand, did not increase or decrease. A few key reasons align for this, namely intergenerational assistance, in which reproductive and non-reproductive females play a role in the development of calves. It has been hypothesized that calves of the 5 Odontoceti species require the assistance of menopausal females to have an enhanced chance at survival, as they are extremely difficult for a single female to successfully rear.[57]

Communication

Like most toothed whales, narwhals use sound to navigate and hunt for food. Narwhals primarily vocalise through "clicks", "whistles" and "knocks", created by air movement between chambers near the

Longevity and mortality factors

Narwhals live an average of 50 years, however, age determination techniques using

In 1914–1915, around 600 narwhal carcasses were discovered after entrapment events, most occurring in areas such as

Major predators are

Conservation

The narwhal is listed as

In 1972, the United States banned commercial imports of products made from narwhal body parts as stated by the

Threats

Narwhals are hunted for their skin, meat, teeth, tusks, and carved vertebrae, which are commercially traded. About 1,000 narwhals are killed per year: 600 in Canada and 400 in Greenland. Canadian harvests were steady at this level in the 1970s, dropped to 300–400 per year in the late 1980s and 1990s and have risen again since 1999. Greenland harvested more, 700–900 per year, in the 1980s and 1990s.[73]

Narwhal tusks are sold both carved and uncarved in Canada

As narwhals grow,

Narwhals are one of the most vulnerable Arctic marine mammals to

Reduction in sea ice has possibly led to increased exposure to predation. In 2002, hunters in

Relationship with humans

Inuit

While it is generally illegal to hunt narwhals,

In Inuit legend, the narwhal's tusk was created when a woman with harpoon rope tied around her waist was dragged into the ocean after the harpoon had stuck into a large narwhal. She was then transformed into a narwhal; her hair, which she was wearing in a twisted knot, became the spiraling narwhal tusk.[84]

Alicorn

The narwhal tusk has been highly sought-after in Europe for centuries. This stems from a medieval belief that narwhal tusks were the horns of the legendary unicorn.[85][86] Trade of narwhal tusks approximately began in 1000.[87] Scientists have long speculated that Vikings collected tusks washed ashore on beaches of Greenland and surrounding areas, yet others predict Norsemen interchanged tusks with Europeans after acquiring them from Inuit. Tusks spread across the Middle East and East Asia. A hypothesis suggests that Norsemen may have hunted narwhals, though this was never confirmed and was later disproven.[88][89] Vikings made weapons out of tusks to be used in battles or hunts. Hadley Meares, a historian, stated, "The trade strengthened during the Middle Ages, when the unicorn became a symbol of Christ, and therefore an almost holy animal."[90] The trade became prevalent in Renaissance times.[91]

Across Europe, narwhal tusks were given as state gifts to kings and queens, in addition to a growing demand for the supposed powers of unicorn horns.

See also

References

- .

- ^ "Monodon monoceros Linnaeus 1758 (narhwal)". PBDB.org. Archived from the original on 12 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ .

- ^ a b "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). "Monodon monoceros". Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata (in Latin). Stockholm: Lars Salvius. p. 824.

- ISBN 978-0-295-80469-9.

- ^ ISBN 87-7975-299-3.

- ^ a b c d e f "The narwhal: unicorn of the seas" (PDF). Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 July 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ Webster, Noah (1880). "Narwhal". An American Dictionary of the English Language. G. & C. Merriam. p. 854.

- ISBN 0-87196-871-1.

- ISBN 0-8018-8221-4.

- ^ ISSN 0824-0469.

- PMID 31221994.

- ^ Pappas, Stephanie (20 June 2019). "First-ever beluga–narwhal hybrid found in the Arctic". Live Science. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- PMID 10837160.

- S2CID 55606151.

- PMID 32315590.

- PMID 30033539.

- S2CID 202018525. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ ISBN 0-691-09160-9. Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ ISSN 0824-0469.

- ^ "Monodon monoceros". Fisheries and Aquaculture Department: Species Fact Sheets. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Archived from the original on 16 February 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2007.

- PMID 18021441.

- ^ ISSN 0824-0469.

- PMID 33627459.

- ^ from the original on 24 January 2024. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- PMID 33972883.

- from the original on 26 January 2024. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ISBN 0-226-50341-0. Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ISBN 978-0-691-23244-7. Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ISSN 1751-8369.

- PMID 34347780.

- from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- from the original on 25 July 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- PMID 24639076.

- ^ a b c Broad, William (13 December 2005). "It's sensitive. Really". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- Independent.co.uk. Archivedfrom the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- PMID 27784729.

- ISBN 978-0-691-23664-3.

- ISSN 0824-0469.

- ^ "For a dentist, the narwhal's smile is a mystery of evolution". Smithsonian Insider. 18 April 2012. Archived from the original on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-12-804327-1, archivedfrom the original on 20 January 2023, retrieved 27 January 2024

- from the original on 27 January 2024. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ from the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ ISSN 0824-0469.

- ^ PMID 18494365.

- ^ ISSN 1095-9289.

- ^ "The biology and ecology of narwhals". noaa.gov. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- ^ ISSN 0171-8630.

- PMID 33122802.

- ^ ISSN 0008-4301.

- ISSN 2050-3385.

- ISBN 2-88032-936-1. Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ISBN 0-935848-47-9. Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ from the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ a b Evans Ogden, Lesley (6 January 2016). "Elusive narwhal babies spotted gathering at Canadian nursery". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- PMID 38480878.

- PMID 29897955.

- ISBN 978-0-691-19062-4. Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ISSN 2071-1050.

- PMID 34772963.

- ISSN 0824-0469.

- ISSN 0824-0469.

- S2CID 246176509.

- ISSN 0022-2372.

- ^ S2CID 253807718.

- JSTOR 207815.

- ISBN 978-0-08-091993-5. Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- PMID 22520955.

- ^ "Invasion of the killer whales: killer whales attack pod of narwhal". Public Broadcasting System. 19 November 2014. Archived from the original on 22 October 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ^ "Fact sheet narwhal and climate change| CITES" (PDF). cms.int. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 January 2024. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- S2CID 89062294, retrieved 14 February 2024

- ^ ISSN 0004-0843.

- ^ Greenfieldboyce, Nell (19 August 2009). "Inuit hunters help scientists track narwhals". NPR.org. National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ^ ISSN 0106-1054.

- ^ ISSN 0706-652X.

- ISBN 978-0-429-21746-3, retrieved 4 February 2024

- ^ ISSN 0171-8630.

- ISSN 0006-3207.

- ISSN 1751-8369.

- ISSN 0006-3207.

- ISSN 2296-7745.

- ISBN 1-85109-533-0.

- ^ S2CID 162878182.

- ISBN 0-942299-91-4.

- S2CID 10030083.

- S2CID 135259639.

- ISSN 2571-9408.

- ^ Berger, Miriam (30 November 2019). "The narwhal tusk has a wondrous and mystical history. A new chapter was added on London Bridge". The Washington Post. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ISSN 0004-3079.

- PMID 38358838.

- ISBN 978-1-317-45938-5. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-84893-270-8, retrieved 13 February 2024

- S2CID 133366872.

- ISBN 978-0-12-809559-1.

- ISBN 978-2-88295-400-8.

- PMID 33944492.

- ^ Meares, Hadley (16 April 2019). "How 'unicorn horns' became the poison antidote of choice for paranoid royals". HISTORY. Retrieved 8 March 2024.

Further reading

- Ford, John; Ford, Deborah (March 1986). "Narwhal: unicorn of the Arctic seas". OCLC 643483454.

- Groc, Isabelle (12 February 2014). "The world's weirdest whale: hunt for the sea unicorn". New Scientist. Retrieved 10 February 2024.