Operation Orator

| Operation Orator | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Arctic naval operations of the Second World War | |||||||

A Hampden TB.1 of the Leuchars Wing makes a torpedo attack on a German vessel during the Second World War. (A photograph taken by a member of 18 Group on an unrelated operation.) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Search & Strike Force

|

(Fighter Wing 5) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

RAAF–RAF 32 long-range torpedo bombers 8 long-range maritime patrol aircraft 5 long-range reconnaissance aircraft |

Kriegsmarine 1 battleship (Tirpitz) 3 cruisers (Admiral Scheer, Admiral Hipper, Köln) 4 destroyers Luftwaffe 35–60 fighters (II./JG 5 and III./JG 5) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Air crew killed: c. 18 POW c. 12 Aircraft: 9 torpedo bombers (en route to USSR) 2 PRU Spitfires | |||||||

Operation Orator was the code name for the defence of the Allied

The Hampden crews made a long and dangerous flight from bases in

At 7:30 a.m. on 14 September, 23 Hampdens were scrambled, after Tirpitz was reported absent from its moorings. The Hampdens flew to the maximum distance that Tirpitz could have reached then turned to follow the track back to Altafjord, as far as the Catalina cross over patrols. After an uneventful flight, the Hampdens returned at 3:00 p.m. from what turned out to be a false alarm; Tirpitz having moved to a nearby fjord. The S&SF Hampdens stayed at readiness and the Spitfires watched over Tirpitz until October. Operation Orator had deterred the Germans from risking their capital ships against PQ 18 and after converting the Soviet Air Forces (VVS) to the Hampden and Spitfire aircraft to be left behind, the aircrew and ground personnel returned to Britain.

Background

Arctic convoys

In October 1941, after

By late 1941, the convoy system used in the Atlantic had been established on the Arctic run; a convoy commodore ensured that the ships' masters and signals officers attended a briefing to make arrangements for the management of the convoy, which sailed in a formation of long rows of short columns. The commodore was usually a retired naval officer, aboard a ship identified by a white pendant with a blue cross. The commodore was assisted by a Naval signals party of four men, who used lamps, semaphore flags and telescopes to pass signals, coded from books carried in a weighted bag, to be dumped overboard in an emergency. In large convoys, the commodore was assisted by vice- and rear-commodores who directed the speed, course and zig-zagging of the merchant ships in co-operation with the escort commander.[3][b]

Convoy hiatus

Following

Signals intelligence

Bletchley Park

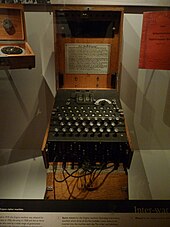

The British

In 1941, naval Headache personnel, with receivers to eavesdrop on Luftwaffe wireless transmissions, were embarked on warships and from May 1942, ships gained RAF Y computor parties, which sailed with cruiser admirals in command of convoy escorts, to interpret Luftwaffe W/T signals intercepted by the Headaches. The Admiralty sent details of Luftwaffe wireless frequencies, call signs and the daily local codes to the computors, which combined with their knowledge of Luftwaffe procedures, could glean fairly accurate details of German reconnaissance sorties. Sometimes computors predicted attacks twenty minutes before they were detected by radar.[6][7]

B-Dienst

The rival German Beobachtungsdienst (B-Dienst, Observation Service) of the Kriegsmarine Marinenachrichtendienst (MND, Naval Intelligence Service) had broken several Admiralty codes and cyphers by 1939, which were used to help Kriegsmarine ships elude British forces and provide opportunities for surprise attacks. From June to August 1940, six British submarines were sunk in the Skaggerak using information gleaned from British wireless signals. In 1941, B-Dienst read signals from the Commander in Chief Western Approaches informing convoys of areas patrolled by U-boats, enabling the submarines to move into "safe" zones.[8] B-Dienst had broken Naval Cypher No 3 in February 1942 and by March was reading up to 80 per cent of the traffic, which continued until 15 December 1943. By coincidence, the British lost access to the Shark cypher and had no information to send in Cypher No 3 which might compromise Ultra.[9] In early September, Finnish Radio Intelligence deciphered a Soviet Air Force transmission which divulged the convoy itinerary and forwarded it to the Germans.[10]

Allied Arctic operations

As Arctic convoys passed by the North Cape of Norway into the

No. 151 Wing RAF (Wing Commander Neville Ramsbottom-Isherwood) flew in the defence of Murmansk for five weeks and claimed 16 victories, four probables and seven aircraft damaged. The winter snows began on 22 September and the conversion of Soviet Air Force (VVS, Voyenno-Vozdushnye Sily) pilots and ground crews to the Hurricane Mk IID began in mid-October and in late November the RAF party returned to Britain, less various signals staff.[12] The Allied Operation Gauntlet (25 August – 3 September 1941), Fritham (30 April 1942 – 2 July 1943) had taken place in the Svalbard Archipelago on the main island of Spitsbergen, midway between northern Norway the North Pole, to eliminate German weather stations and to stop its coal exports to Norway.[13] In Operation Gearbox II (2–21 September 1942) two cruisers and a destroyer took 200 long tons (203 t) of supplies and equipment to Spitsbergen.[14] On 3 September, Force P, the oilers RFA Blue Ranger, RFA Oligarch and four destroyer escorts sailed for Van Mijenfjorden (Lowe Sound) in Spitsbergen and from 9 to 13 September refuelled destroyers detached from PQ 18.[15]

German plans

Authority in the Kriegsmarine was derived from the Seekriegsleitung (Supreme Naval Command) in Berlin and Arctic operations were commanded by Admiral Boehm, the Admiral Commanding Norway, from the Marinegruppenkommando Nord (Naval Group North) HQ in Kiel. Three flag officers were detached to Oslo in command of minesweeping, coast defence, patrols and minelaying off the west, north and polar coasts. The large surface ships and U-boats were under the command of the Flag Officer Northern Waters at Narvik, who did not answer to Boehm but had authority over the Flag Officer Battlegroup, who commanded the ships when at sea. The Flag Officer Northern Waters also had tactical control of aircraft from Luftflotte 5 (Generaloberst Hans-Jürgen Stumpff) when they operated in support of the Kriegsmarine. The Norwegian-based aircraft had tactical headquarters at Kirkenes, Trondheim and Bardufoss. The Luftwaffe HQs were separate from the Kriegsmarine commanders except at Kirkenes, with the Flag Officer Polar Coast.[16]

On 24 June, a British minesweeper based at Kola was sunk by

Goldene Zange (Golden Comb)

The Luftwaffe used the lull after PQ 17 to assemble a force of 35 Junkers Ju 88 A-4 dive-bombers of Kampfgeschwader 30 (KG 30) and 42 torpedo-bombers of Kampfgeschwader 26 (KG 26) (I/KG 26 with 28 Heinkel He 111 H-6s and III/KG 26 with 14 Ju 88 A-4s) to join the reconnaissance aircraft of Luftflotte 5.[22][23] After analysing the results of anti-shipping operations against PQ 17, in which the crews of Luftflotte 5 made exaggerated claims of ships sunk, including a cruiser, the anti-shipping units devised the Goldene Zange (Golden Comb). Ju 88 bombers were to divert the defenders with medium and dive bombing attacks as the torpedo-bombers approached out of the twilight. The torpedo bombers were to fly towards the convoy in line abreast, at wave-top height to evade radar, as the convoy was silhouetted against the lighter sky, then drop their torpedoes in a salvo.[24] When B-Dienst discovered that an aircraft carrier would accompany the next convoy, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring gave orders that it must be sunk first; Luftwaffe aircrew were told that the destruction of the convoy was the best way to help the German army at Stalingrad and in southern Russia.[25]

Operation Orator

Plan

A Search & Strike Force (S&SF), commanded by Group Captain

Deployment of the Search & Strike Force

On 13 August, Hopps, RAF and RAAF ground staff and a medical unit sailed for Russia on the cruiser Tuscaloosa, along with three destroyers (two US and one British).

On 2 September 1942, as PQ 18 departed from

Late on 4 September, the Hampdens of the Leuchars Wing took off for Russia. Their route would keep the Hampdens a minimum of 60 nmi (69 mi; 110 km) from German-occupied territory but was clearly too risky. A flight along the Norwegian coast would cover 1,200 nmi (1,400 mi; 2,200 km), parts easily in range of the Luftwaffe. A direct route over the mountains of Norway would be only 1,100 nmi (1,300 mi; 2,000 km) long but the fuel consumed in climbing high enough would leave little left to overcome head winds, engine trouble, navigation errors or a landing delay.[32] The Hampden crews were to follow a route similar to that of the Spitfires, flying north to Burrafirth in Shetland and the fly on a course to reach Norway at 66°N, cross the mountains in the dark, overfly northern Sweden and Finland, before landing at the Soviet air base at Afrikanda, at the southern end of Murmansk Oblast. The flight to Afrikanda was expected to take five to eight hours, depending on the weather and German opposition. After refuelling, the Hampden crews were to fly the remaining 120 mi (190 km) to Vayenga, following the Kandalaksha–Murmansk railway northwards.[34]

Two Hampdens crashed in northern Sweden, near

Four Hampdens were either shot down or forced to land in German-held territory. AT109 ("UB-C") of 455 Squadron, piloted by Sqn Ldr

Poor visibility in the Afrikanda area made landings difficult and two Hampden pilots, Sqn Ldr Dennis Foster (144 Sqn) and Sqn Ldr Jack Davenport (455 Sqn), landed on a mud airstrip at Monchegorsk, about 30 mi (48 km) to the north. Davenport did so after his Hampden was intercepted by VVS fighter pilots, who directed him to land.[44][45] Two Hampdens ran out of fuel over Russia and were damaged in forced landings at or near Afrikanda. One pilot made a wheels-up landing in soft ground at Khibiniy, several miles north of Afrikanda and the other Hampden was written off after hitting tree stumps. A further Hampden was lost on the Afrikanda–Murmansk leg. AE356, piloted by Sgt Walter Hood (144 Sqn), was caught up in a German air raid over the Kola Inlet and was attacked in error by VVS fighter pilots. Forced to ditch in a lake, the crew were strafed in the water and the ventral gunner, Sgt Walter Tabor (RCAF) died, either from bullet wounds or drowning when the aircraft sank. The survivors got ashore and received small-arms fire from Soviet troops until they were recognised as Allies (from their shouts of "Angliski"); 23 Hampdens arrived at Soviet airfields intact or with only minor damage.[17][29]

Convoy PQ 18

The German surface force at Narvik had been alerted when PQ 18 was first sighted and on 10 September sailed north to Altafjord past the British submarines HMS Tribune and HMS Tigris.[17] Tigris made an abortive torpedo attack on Admiral Scheer and erroneously reported it as Tirpitz.[46] Soon after midnight on 10/11 September, the Admiralty supplied Enigma messages to the British escort commander that Admiral Hipper was due at Altafjord at 3:00 a.m. and in the afternoon reported that Tirpitz was still at Narvik. On 13 September, Enigma showed that the ships at Altafjord had come to one hours' notice at 4:50 p.m. which was relayed to the convoy escort commander at 11:25 p.m. Enigma showed that Tirpitz was still in Narvik on 14 September and on 16 September, a Swedish source, A2, reported that only Admiral Hipper, Admiral Scheer and Koln would operate against PQ 18. Doppeslschlag had already been called off on 13 September; Hitler, reluctant to risk the loss of any of his capital ships on an offensive operation, had refused to authorise a sortie.[47]

Scheer and its escorts remained far to the north of PQ 18 as the convoy rounded the North Cape. Operation EV, the escort operation for the forty Allied freighters in the convoy comprised an exceptionally large number of navy ships, including Avenger, the first escort carrier to accompany an Arctic convoy. Detailed information on German intentions was provided by Allied code breakers, through Ultra signals decrypts and eavesdropping on Luftwaffe wireless communications. From 12 to 21 September, PQ 18 was attacked by bombers, torpedo-bombers, U-boats and mines, which sank thirteen ships at a cost of forty-four aircraft and four U-boats. The escort ships and the aircraft of Avenger were able to use signals intelligence from the Admiralty to provide early warning of some air attacks and to attempt evasive routeing of the convoy around concentrations of U-boats. The convoy handed over its distant escorts and Avenger to the homeward bound Convoy QP 14 near Archangelsk on 16 September and continued with the close escort and local escorts, riding out a storm in the northern Dvina estuary and the last attacks by the Luftwaffe, before reaching Archangelsk on 21 September.[48]

Air operations from Russia

The Catalinas of 210 Squadron were to provide a close escort for PQ 18 at the beginning and end of its journey. The aircraft based at Shetland and Iceland carried depth charges instead of overload tanks and on 23 September, an aircraft from Shetland sank U-253, 115 nmi (132 mi; 213 km) off Cape Langanaes, Iceland. The Catalina detachment based in Russia carried overload tanks instead of depth charges and could only menace the U-boats and report their positions to Allied naval ships. The main task of the Catalinas was to maintain ten crossover patrols, AA to KK, 100 nmi (120 mi; 190 km) from the Norwegian coast, from west of Narvik to east of the North Cape. It would be impossible for a sortie by the German ships in north Norway to pass through without being detected by Air to Surface Vessel (ASV) radar. As PQ 18 sailed around Norway, the patrol areas moved north-eastwards; AA to CC were flown by the Catalinas from Shetland, as were DD to EE but the aircraft flew on to Russia. EE was the furthest from both bases and five aircraft were necessary to keep continuously one aircraft in the patrol area; areas FF to KK were flown by the detachment in Russia. The flights from Shetland could take 16 hours before the first landfall and low stratus cloud often prevented celestial navigation, the crew having to rely on dead reckoning instead.[49]

The Catalinas detached to Russia, were based at Lake Lakhta near Archangelsk on the White Sea; using Grasnaya on the Kola Inlet as an advanced base. The communications between them were impossible; Hopps used Grasnaya instead, which was 400 nmi (460 mi; 740 km) nearer to the patrol areas and equally closer to occupied Norway. Lake Lakhta became a rest area and the base for close escort of PQ 18, once it was on the final leg of the journey. The Catalinas bound for Russia left Shetland in sequence, completed the circuits of their patrol area and proceeded to Russia. From above, the Arctic tundra looked uninviting but having landed, the crews found the Soviet Naval Aviation (Morskaya Aviatsiya) base at Lake Lakhta an idyllic setting, lying amidst woods and cliffs. Russian ground crews were found to be very efficient, impressing the British with their ability to improvise. The damaged Hampden from Khibiniy was put back into service and a Catalina damaged by a Luftwaffe aircraft was hauled ashore within eight minutes of landing and swiftly repaired; once begun, work went on until aircraft were serviceable. The flight from Lake Lakhta to Grasnaya took about five hours and once over PQ 18, the Catalina would circle it, keeping a careful watch on aircraft nearby in case of mistaken identity. [50]

By 5 September, the serviceable Hampdens were at Vayenga, further back from the front line than Polyarny. The airfield was bombed several times by the Luftwaffe and a Spitfire to be written off on 9 September but there were no casualties.[51] An Area Combined HQ was set up at Polyarny, where a Senior British Naval Officer, Rear-Admiral Douglas Fisher was already installed.[52] The PR Spitfires at Vayenga had their RAF roundels painted out and replaced by red stars: oblique F 24 cameras were used on twelve sorties to Narvik and Altafjord, flying through foul weather to keep watch over the German ships.[1] To replace the written off Spitfire, 1 PRU despatched another Spitfire, which arrived from Britain on 16 September, along with a de Havilland Mosquito PR Mk I (W4061).[51]

On the night of 13/14 September, communications between PQ 18 and Lake Lakhta failed, a Catalina at Grasnaya was unable to take off until dawn and the PR sortie found Altafjord covered by cloud. If the Catalina sent a sighting report, it would come too late for the Hampdens to attack and as a precaution, Hopps ordered the 23 operational Hampdens up 5:00 a.m. on 14 September, for a reconnaissance in force.

By late September, the S&SF was experiencing increased attention from the Luftwaffe. The Hampdens remained dispersed around Vayenga airfield, receiving some damage during air raids.

Aftermath

Analysis

Operation Orator was called a success by J. H. W. Lawson in his history of 455 Squadron (1951) and in 1975, Peter Smith wrote that intelligence from B-Dienst and documents recovered from the Hampden crash about Operation Orator may have deterred a surface attack on PQ 18 by Scheer and its escorts.[59][60][17] In the 2005 edition of Arctic Airmen... Ernest Schofield and Roy Nesbit wrote that "it is reasonable to assume that the aircraft based in north Russia had worried the German commander".[61][i] Chris Mann in a 2012 study of British wartime strategy towards Norway, called it an expensive victory and in 2017, Jan Forsgren in a book on RAF attacks on Tirpitz called the operation a success, because no Axis surface vessels approached PQ 18.[62][51] PQ 18 was also judged a success by the Allies, having revived the Arctic convoy route to the USSR and because Tirpitz, Admiral Scheer, Admiral Hipper and Köln had been deterred by Operation Orator from attacking the convoy.[62]

In 2011, Michael Walling called the loss of nine Hampdens on the transit flight, the equivalent of the loss anticipated on an attack against a big warship, a disaster.[63] The surviving Hampdens were to be flown back to Scotland but the crews had doubts about the prevailing west–east headwinds, which could push the aircraft beyond their maximum range.[64] Wing Commander Grant Lindeman, the CO of 455 Squadron, called the flight "suicidal".[51] On 1 October, Soviet authorities made a formal request for the Hampdens.[51] The RAF agreed to donate the Hampdens and PR Spitfires to the VVS; S&SF personnel were to return to Britain by sea after helping to convert the Soviet air- and ground-crews to both types.[65][66][51] RAAF and RAF personnel returned to Britain on 28 October in HMS Argonaut.[64] All but one of the Catalinas was flown back to Britain, once QP 14 had passed through the danger zone.[67]

Aircraft losses

Handley-Page Hampden TB 1 (4–5 September 1942)

144 Squadron RAF (squadron code prefix "PL")

- AE310 squadron code unknown, pilot unknown: fuel shortage over Afrikanda led to a forced landing, the crew was unhurt but the aircraft was damaged.[36][68] (AE310 or P5323 was repaired and returned to service.)[36]

- AE436 "PL-J", Pilot Officer (P/O) D. I. Evans: icing affected the Hampden, an engine overheated and it crashed on the Tsatsa massif near Kvikkjokk in Sweden, 15 mi (24 km) north of track. Evans and his supernumerary survived and walked for three days to Kvikkvok 20 mi (32 km) away.[69] At risk of internment for violating Swedish neutrality, they claimed to have crashed in Norway and were later repatriated to the UK.[41][36]

- AE356 "PL-?", Sergeant Walter Hood: shot down accidentally by fighters of the VVS into a lake near Murmansk, ventral gunner died of wounds and/or drowning.[70]

- AT138 "PL-C", Sergeant John Bray: attacked by a fighter belonging to Jagdgeschwader 5 (JG 5) over Finland; three crew and one passenger were killed; Bray bailed out and became a prisoner of war. AT138 crashed near Alakurtti.[39][36]

- P1273 "PL-Q", Sergeant Harry Bertrand: attacked by fighters from JG 5 over Finland; the crew and their passenger bailed out and became Prisoners of war. PL-Q crashed in a swamp near Petsamo (later known as Pechenga).[36]

- P1344 "PL-K", P/O E. H. E. Perry: damaged by flak, as it passed directly over Petsamo airfield and subsequently attacked by two Messerschmitt Bf 109s of JG 5. During a crash-landing in an Axis-held part of the Kola Peninsula, three crewmembers were killed and Perry was seriously injured. He and his passenger were taken prisoner.[36] [40]

455 Squadron RAAF (squadron code prefix "UB")

- AT109 "UB-C", Squadron Leader James Catanach: strayed north of track, flak damage from submarine chaser UJ 1105 off the coast of Norway led to a forced landing on a beach at Molvika, near Kiberg and the crew being taken prisoner.[43][j]

- P5304 "UB-H", Sergeant E. J. "Sandy" Smart: shot down over Sweden near Arvestuottar lake, north of Arjeplog, by a German fighter from Bodø; no survivors.[71]

- P5323 "UB-L", P/O Rupert "Jeep" Patrick: ran out of fuel, made a wheels-up landing in an area of cut-down silver birch at Kandalaksha, Russia without casualties; the aircraft was damaged.[72][73] (Either P5323 or AE310 was repaired and returned to service.)[36]

Supermarine Spitfire PR Mk IV(D) (9–27 September 1942)

1 PRU RAF (squadron code prefix "LY")

- Build number and squadron code unknown, damaged on the ground during a German air raid at Vayenga (9 September 1942) and written off.[51]

- BP889, squadron code unknown, Banak airfield), flying a Focke-Wulf Fw 190 fighter.[56]

Notes

- ^ The cruiser USS Tuscaloosa carried most of the RAAF–RAF ground staff and a medical unit to Russia.[1]

- Asdic and bulk commodities.[4]

- ^ Destroyers USS Rodman, USS Emmons and HMS Onslaught. The ships began the return journey on 24 August, with survivors from PQ 17.[30]

- Sami reindeer herder, told Jörgensen that a twin-engined aircraft had been shot down in early September 1942 near Arvedstuottar, after crossing the Swedish border near Strimasund. Grufvisare claimed to have seen the shooting down from the Karats area, had been so frightened that he abandoned his herd, returned to his home in Jokkmokk and reported the incident to police.[35]

- ^ The wreckage of the Hampden and the remains of those killed in the crash were found 5,000 ft (1,500 m) up Tsatsa in 1976.[38]

- Warrant Officer. (Australian Ex-Prisoners of War Memorial, 2013–2018, World War 2 (B) Access date: 17 June 2018.) The location of the wreck was discovered in 1991 and the crew were buried with full military honours at the Allied cemetery in Arkhangelsk in 1993.(The Herald, 1993, "Laid to rest with tears and a salute, the four heroes who gave their lives in a foreign field". Access date: 17 June 2018.)

- ^ Sergeant Henry Lewis (Hank) Bertrand 10772247 was a Canadian serving in the RAF.[42]

- ^ The authors also wrote that the operations at Spitsbergen had an indirect influence on the success of PQ 18, because Fritham and Gearbox made it safe for tankers to anchor and refuel destroyer escorts from the convoy, free from interference by German ground forces.[61]

- ^ Catanach was shot by the Germans for his part in the Great Escape.[43]

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d Schofield & Nesbit 2005, p. 195.

- ^ Woodman 2004, p. 14.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Edgerton 2011, p. 75.

- ^ Roskill 1962, pp. 278–281.

- ^ a b Macksey 2004, pp. 141–142.

- ^ a b Hinsley 1994, pp. 141, 145–146.

- ^ Kahn 1973, pp. 238–241.

- ^ Budiansky 2000, pp. 250, 289.

- ^ FIB 1996.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Richards & Saunders 1975, pp. 78–80.

- ^ Roskill 1957, p. 489.

- ^ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Roskill 1962, pp. 280–283.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b c d e f Smith 1975, p. 124.

- ^ a b Walling 2012, p. 214.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 258–259.

- ^ Roskill 1962, pp. 279–280.

- ^ Roskill 1962, pp. 281–282.

- ^ Bekker 1966, pp. 394–398.

- ^ Wood & Gunston 1990, pp. 70, 72.

- ^ PRO 2001, p. 114.

- ^ Woodman 2004, p. 262.

- ^ Schofield & Nesbit 1987, p. 195.

- ^ a b CWGC 2018.

- ^ Greenhous 1994, pp. 180–181.

- ^ a b Richards & Saunders 1975, pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b Woodman 2004, p. 258.

- ^ Schofield & Nesbit 1987, p. 191.

- ^ a b Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Walling 2012, pp. 201–202.

- ^ a b Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 192–194.

- ^ Bengt Hermansson 1942-09-05 Handley-Page HP 52 Hampden TB 1 - Serial # P5304 455 Squadron, Leuchars, Skottland forcedlandingcollection.se (12 June 2018).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Sorenson 2011.

- ^ Alexander 2009, p. 467.

- ^ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, p. 194.

- ^ a b c Walling 2012, pp. 201–209.

- ^ a b RAF Museum 2016.

- ^ a b Hermansson 2016.

- ^ Edmonton Journal, 2011, "BERTRAND, Henry Lewis (Hank)" (8 March). (17 June 2018).

- ^ a b c Walling 2012, p. 207.

- ^ Alexander 2009, pp. 138–9.

- ^ Gordon 1995, p. 15.

- ^ Woodman 2004, p. 265.

- ^ a b Roskill 1962, pp. 284, 287–288.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 258–283.

- ^ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 195–197.

- ^ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 197–198, 200–203.

- ^ a b c d e f g Forsgren 2017, p. 60.

- ^ Roskill 1962, p. 279.

- ^ Herington 1954, pp. 296–297.

- ^ Schofield & Nesbit 1987, pp. 184–185.

- ^ Schofield & Nesbit 1987, pp. 185–186.

- ^ a b Weal 2016, p. 58.

- ^ a b Forsgren 2017, pp. 60–1.

- ^ AWM nd; Alexander 2009, p. 147.

- ^ Lawson 1951, p. 73.

- ^ Hinsley 1994, p. 154.

- ^ a b Schofield & Nesbit 2005, p. 206.

- ^ a b Mann 2012, p. 24.

- ^ Walling 2012, p. 209.

- ^ a b Richards & Saunders 1975, p. 83.

- ^ Richards & Saunders 1975, p. 82.

- ^ Schofield & Nesbit 1987, p. 186.

- ^ Richards & Saunders 1975, p. 93.

- ^ Schofield & Nesbit 1987, pp. 201.

- ^ Walling 2012, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Walling 2012, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Walling 2012, pp. 204, 207–208.

- ^ Walling 2012, p. 206.

- ^ Alexander 2009, pp. 133–142.

Bibliography

Books

- Alexander, Kristin (2009). Jack Davenport, Beaufighter Leader (e-book ed.). Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-282-23908-1.

- Bekker, Cajus (1966). The Luftwaffe War Diaries. New York: Ballantine. OCLC 657996667.

- Budiansky, S. (2000). Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War II. New York: The Free Press (Simon & Schuster). ISBN 0-684-85932-7– via Archive Foundation.

- ISBN 978-0-7139-9918-1.

- Forsgren, Jan (2017). Sinking the Beast: The RAF 1944 Lancaster Raids Against Tirpitz. Oxford: Fonthill Media. ISBN 978-1-78155-318-3.

- Gordon, Ian (1995). Strike and Strike Again: 455 Squadron RAAF, 1944–45. Belconnen, ACT: Banner Books. ISBN 978-1-875593-09-5.

- Greenhous, B.; et al. (1994). The Official History of the Royal Canadian Air Force: The Crucible of War, 1939–1945. Vol. III. Toronto: University of Toronto Press and Department of National Defence. ISBN 978-0-8020-0574-8. D2-63/3-1994E.

- Herington, John (1954). "Chapter 11, The Air War at Sea: January to September 1942". Air War Against Germany and Italy, 1939–1943. Australia in the War of 1939–1945 Series 3 – Air. Vol. III (1st [online] ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. pp. 262–297. OCLC 493504443. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- Hinsley, F. H. (1994) [1993]. British Intelligence in the Second World War: Its Influence on Strategy and Operations. History of the Second World War (2nd rev. abr. ed.). London: ISBN 978-0-11-630961-7.

- Kahn, D. (1973) [1967]. The Codebreakers: The Story of Secret Writing (10th abr. Signet, Chicago ed.). New York: Macmillan. OCLC 78083316.

- Lawson, J. H. W. (1951). Four Five Five: The story of 455 (R.A.A.F.) Squadron. Melbourne, Aus: Wilke. OCLC 19796160.

- ISBN 978-0-304-36651-4.

- Mann, C. (2012). British Policy and Strategy towards Norway, 1941–45. Studies in Military and Strategic History. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-21022-6.

- Richards, Denis; Saunders, H. St G. (1975) [1954]. Royal Air Force 1939–1945: The Fight Avails. History of the Second World War, Military Series. Vol. II (pbk. ed.). London: ISBN 978-0-11-771593-6. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- OCLC 881709135. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- Roskill, S. W. (1962) [1956]. The Period of Balance. OCLC 174453986. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- Schofield, Ernest; Nesbit, Roy Conyers (1987). Arctic Airmen: The RAF in Spitsbergen and North Russia 1942. London: W. Kimber. ISBN 978-0-7183-0660-1.

- Schofield, Ernest; Nesbit, Roy Conyers (2005) [1987]. Arctic Airmen: The RAF in Spitsbergen and North Russia 1942 (2nd repr. Spellmount, Staplehurst ed.). London: W. Kimber. ISBN 978-1-86227-291-0.

- Smith, Peter (1975). Convoy PQ18: Arctic Victory. London: Kimber. ISBN 978-0-7183-0074-6.

- The Rise and Fall of the German Air Force (facs. repr. Public Record Office War Histories ed.). Richmond, Surrey: Air Ministry. 2001 [1948]. ISBN 978-1-903365-30-4. Air 41/10 number 248.

- Walling, M. G. (2012). Forgotten Sacrifice: The Arctic Convoys of World War II. General Military. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84908-718-6.

- Weal, John (2016). Arctic Bf 109 and Bf 110 Aces. Oxford UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-7820-0799-9.

- Wood, Tony; Gunston, Bill (1990). Hitler's Luftwaffe. New York: Crescent Books. OCLC 704898536.

- Woodman, Richard (2004) [1994]. Arctic Convoys 1941–1945. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5752-1.

Websites

- "Birth of Radio Intelligence in Finland and its Developer Reino Hallamaa". Pohjois–Kymenlaakson Asehistoriallinen Yhdistys Ry (North-Karelia Historical Association Ry) (in Finnish). 1996. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- Löwenstein, Magnus (2012). Hermansson, Bengt (ed.). "5 September 1942: Handley-Page HP52 Hampden TB.1, Serial AE436". Forced Landing Collection. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Socks: Pilot Officer A W Bowman, 455 Squadron, RAAF". Australian War Memorial. nd. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- Sorenson, Kjell (2011). "Handley Page HP52 Hampden Tsatsa, Sarek Sweden". flyvrak© World War II Aircraft Wreck Sites in Norway & Other Countries. Archived from the original on 18 January 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Student helps Restore Great Grandfather's Hampden Bomber". Royal Air Force Museum. 2016. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- "War: Second World War Sweden: 4 September 1942 to 5 September 1942". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. 2018. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

Further reading

Books

- Raebel, G. W. (2010). The R.A.A.F. in Russia: 455 RAAF Squadron: 1942 (2nd ed.). Loftus, NSW: 455 Productions. ISBN 978-0-9586693-5-1.

- ISBN 0-75381-130-8.

Websites

- Cowan, Brendan (2016). "Adf-Serials: Australian & New Zealand Military Aircraft Serials & History, RAAF Handley Page HP.52 Hampden Mk.I & TB. Mk.I: 455 Sqn, RAAF". Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- Löwenstein, Magnus (2012). Hermansson, Bengt (ed.). "5 September 1942: Handley-Page HP 52 Hampden TB 1, Serial P5304". Forced Landing Collection. Retrieved 16 April 2018.