Orientalism in early modern France

In

Early study of Oriental languages

The first attempts to study oriental languages were made by the Church in Rome, with the establishment of the Studia Linguarum in order to help the Dominicans liberate Christian captives in Islamic lands. The first school was established in Tunis by Raymond of Penyafort in the 12th and early 13th century.[2] In 1311, the Council of Vienne decided to create schools for the study of oriental languages in the universities of Paris, Bologna, Oxford, Salamanca and Rome.[2]

The first Orientalist, Guillaume Postel (1536)

From the 16th century, the study of oriental languages and cultures was progressively transferred from religious to royal patronage, as Francis I sought an alliance with the Ottoman Empire.[3] Ottoman embassies soon visited France, one in 1533, and another the following year.[3]

Scientific exchange is thought to have occurred, as numerous works in Arabic, especially pertaining to

Guillaume Postel envisioned a world where

Postel also studied languages and sought to identify the common origin of all languages, before Babel.[6] He became Professor of Mathematics and Oriental Languages, as well as the first professor of Arabic, at the Collège royal.

Second embassy to the Ottoman Empire (1547)

Scientific research

In 1547, a second embassy was sent by the French king to the Ottoman Empire, led by

Political studies

Knowledge of the Ottoman Empire allowed French philosophers to make comparative studies between the political systems of different nations.

The arts

French novels and tragedies were written with the Ottoman Empire as a theme or background. were notable fashions that affected a wide range of the decorative arts.

Oriental studies

Oriental studies continued to take place towards the end of the 16th century, especially with the work of

While in Rome he set up a publishing house, the Typographia Savariana, through which he printed a Latin-Arab bilingual edition of a catechism of Cardinal

In 1610–11,

A protégé of Savary de Brèves,

According to McCabe, Orientalism played a key role "in the birth of science and in the creation of the French Academy of Sciences".[19]

Development of trade

France started to set up numerous

Coffee drinking

An Ottoman embassy was sent to

Manufacture of "Oriental" luxury goods in France

Right image: French adaptation: Tapis de Savonnerie, under Louis XIV, after Charles Le Brun, made for the Grande Galerie in the Louvre Palace.

The establishment of strong diplomatic and commercial relations with the

Silk manufacturing

Henry IV made the earliest attempt at producing substitutes for luxury goods from the Orient. He experimented with planting

During the 17th century, from being an importer, France became a net exporter of silk, for example shipping 30,000 pounds sterling worth of silk to England in 1674 alone.[29]

Turkish carpet-making

The

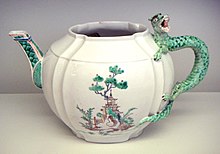

Chinese porcelain

Chinese porcelain was collected at the French court from the time of Francis I.

France was one of the first European countries to produce

France however, only discovered the Chinese technique of

Textiles: Siamoises and Indiennes

The Siamese Embassy to France in 1686 had brought to the Court samples of multicolor Thai Ikat textiles. These were enthusiastically adopted by the French nobility to become Toiles flammées or Siamoises de Rouen, often with checkered blue-and-white designs.[35] After the French Revolution and its dislike for foreign luxury, the textiles were named "Toiles des Charentes" or cottons of Provence.[36]

Textiles imported from

Literature

French literature also was greatly influenced. The first French version of

By that time, the

In particular, cultural diversity with respect to religious beliefs could no longer be ignored. As Herbert wrote in On Lay Religion (De Religione Laici, 1645):

Many faiths or religions, clearly, exist or once existed in various countries and ages, and certainly there is not one of them that the lawgivers have not pronounced to be as it were divinely ordained, so that the Wayfarer finds one in Europe, another in Africa, and in Asia, still another in the very Indies.

Starting with Grosrichard, analogies were also made between the harem, the Sultan's court, oriental

Visual arts

By the end of the 17th century, the first major defeats of the Ottoman Empire reduced the perceived threat in European minds, which led to an artistic craze for things Turkish,

Cultural impact

According to historian McCabe, early orientalism profoundly shaped French culture and gave it many of its modern characteristics. In the area of science, she stressed "the role of Orientalism in the birth of science and in the creation of the

See also

- France-Asia relations

- Felix Thomas

- Julius Oppert

- Orientalism

- Société des Peintres Orientalistes Français (Society for French Orientalist Painters)

- Turquerie

Notes

- ISBN 978-1-84520-374-0, Berg Publishing, Oxford

- ^ a b McCabe, p.29

- ^ a b c McCabe, p.37

- ^ McCabe, p.44

- ^ Whose Science is Arabic Science in Renaissance Europe? by George Saliba Columbia University

- ^ a b McCabe, p.15

- ^ McCabe, p.40-41

- ^ McCabe, p.48

- ^ a b c McCabe, p.61

- ^ a b Ecouen Museum exhibit

- ^ The Literature of the French Renaissance by Arthur Augustus Tilley, p.87 [1]

- ^ The Penny cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge p.418 [2]

- ^ Marbled paper: its history, techniques, and patterns by Richard J. Wolfe p.35

- ^ a b The Encyclopaedia of Islam: Fascicules 111–112 : Masrah Mawlid by Clifford Edmund Bosworth p.799

- ^ a b c d Eastern wisedome and learning: the study of Arabic in seventeenth-century... G. J. Toomer p.30ff

- ^ Eastern wisedome and learning: the study of Arabic in seventeenth-century Europe by G. J. Toomer p.43ff

- ^ Romania Arabica by Gerard Wiegers p.410

- ^ a b McCabe, p.97

- ^ a b McCabe, p.3

- ^ McCabe, p.98

- ^ Bluche, François. "Louis XIV", p. 439, Hachette Litteratures, Paris (1986).

- ^ Göçek, p.8

- ^ Goody, p.73

- ^ Bernstein, p.247

- ^ New York Times Starbucked, 16 December 2007

- ^ Bound together by Nayan Chanda p.88

- ^ Bound together by Nayan Chanda p.87

- ^ McCabe, p.8

- ^ McCabe, p.6

- ^ Paris as it was and as it is, or, A sketch of the French capital by Francis William Blagdon p.512 [3]

- ^ a b Chinese glazes: their origins, chemistry, and recreation Nigel Wood p.240

- ^ The Grove encyclopedia of materials and techniques in art Gerald W. R. Ward p.38

- ^ a b c d McCabe, p.220ff

- ^ a b Artificial Soft Paste Porcelain – France, Italy, Spain and England Edwin Atlee Barber p.5–6

- ^ McCabe, p.222

- ^ a b McCabe, p.223

- ^ a b c d Goody, p.75

- ISBN 0-89073-050-4

- ISBN 0-521-54724-5

- ISBN 978-1-84520-374-0. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ^ McCabe, p.5

References

- McCabe, Ina Baghdiantz. 2008. Orientalism in Early Modern France. Oxford: Berg. ISBN 978-1-84520-374-0.

- Dew, Nicholas. 2009. Orientalism in Louis XIV's France. Oxford: ISBN 978-0-19-923484-4.