Punic religion

The Punic religion, Carthaginian religion, or Western Phoenician religion in the western Mediterranean was a direct continuation of the

Pantheon

The Punics derived the original core of their religion from Phoenicia, but also developed their own pantheons.

It is difficult to reconstruct a hierarchy of the Carthaginian gods.

Different Punic centres had their own distinct pantheons. In Punic Sardinia, Sid or Sid Babi (known to the Romans as

Following the common practice of

An important source on the Carthaginian pantheon is a treaty between Hamilcar of Carthage and Philip III of Macedon preserved by the second-century BC Greek historian Polybius which lists the Carthaginian gods under Greek names, in a set of three triads. Shared formulas and phrasing show it belongs to a Near Eastern treaty tradition, with parallels attested in Hittite, Akkadian, and Aramaic.[18][19] Given the inconsistencies in identifications by Greco-Roman authors, it is not clear which Carthaginian gods are to be interpreted.[8] Paolo Xella and Michael Barré (followed by Clifford) have put forward different identifications.[15][18][19] Barré has also connected his identifications with Tyrian and Ugaritic predecessors[19]

| Greek god |

Carthaginian god (Xella)[15] |

Carthaginian god (Barré, Clifford)[19][18] |

Tyrian god |

Ugaritic god |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zeus | Baal Hammon | Baal Hammon | Bayt-il | El |

| Hera | Tanit | Tanit | Anat-Bayt-il | Anat |

| Apollo | Eshmun? | Reshef | —

|

Reshep |

| [“Daimon of the Carthaginians”] | Gad? | Ashtarte | Ashtarte | Attart |

| Herakles | Melqart | Melqart | Milqart | Milk |

Iolaos

|

[“problematic”] | Eshmun | Eshmun | ?

|

| Ares | Reshef? | Baal Shamem | Baal Shamem | Haddu |

| Triton | [“Maritime deity”] | Kushor | Baal Malaqe | Kotaru |

| Poseidon | [“Maritime deity”] | Baal Saphon | Baal Sapun | Balu-Sapani (=Haddu) |

The Carthaginians also adopted the Greek cults of Persephone (Kore) and Demeter in 396 BCE as a result of a plague that was seen as divine retribution for the Carthaginian desecration of these goddesses' shrines at Syracuse.[20] Nevertheless, Carthaginian religion did not undergo any significant Hellenization.[21] The Egyptian deities Bes, Bastet, Isis, Osiris and Ra were also worshiped.[22][8]

There is very little evidence for a Punic

Practices

Priesthood

The Carthaginians appear to have had both part-time and full-time priests, the latter called khnm (singular khn, cognate with the

Funerary practices

The funerary practices of the Carthaginians were very similar to those of Phoenicians located in

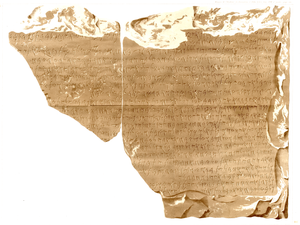

Cemeteries were located outside settlements.[33] They were often symbolically separated from them by geographic features like rivers or valleys.[34] A short papyrus found in a tomb at Tal-Virtù in Malta suggests a belief that the dead had to cross a body of water to enter the afterlife.[35] Tombs could take the form of fossae (rectangular graves cut into the earth or bedrock), pozzi (shallow, round pits), and hypogea (rock-cut chambers with stone benches on which the deceased was laid). There are some built tombs, all from before the sixth century BC.[36][37] Tombs are often surmounted by small funerary stelae and baetyls.

At different times, Punic people practiced both

The funeral was accompanied by a feast in the cemetery.

A range of grave goods are found deposited with the deceased, which seem to have been intended to provide the deceased with protection and symbolic nourishment.

Funerary iconography

Most Punic grave stelae, in addition to an engraved text and sometimes a standing figure bearing a libation cup, show a standard repertoire of (religious) symbols. It is thought that such symbols, which may be compared to a cross on a Christian gravestone, generally represent "deities or beliefs related to the after-life, aimed probably at facilitating or at protecting the eternal rest of the deceased".[67] The symbols also helped the large majority of people who were illiterate to understand the function of the stela.[68]

The main Punic funerary symbols are:[68][69]

- the so-called "Tanit symbol", a female figure built up from a triangle (the body), plus a circle (the head), and a horizontal line (the arms, often with hands stretched out upwards). The symbol often appears on stelae dedicated to the two gods "Tinnit-Phanebal and Baal-Hammon". Of unknown origin, unlike the other funerary symbols, the worship of Tanit (or Tinnit) seems autochthonous: it is found hardly anywhere else but in Punic culture. Little is known about Tanit, but she is considered to be a symbol of fertility and abundance (the Tanit symbol also looks very similar to the Egyptian Ankh symbol, a symbol of life). The Tanit symbol is found most often in the neo-Punic period (after 146 BCE).

- the "crescent and disc", a very common symbol on Carthaginian grave stelae, a circle covered by a sickle. Probably portraying the new ("crescent") and full ("disc") moon.[70] This symbol seems to refer to the passage of time, but the precise meaning is unknown. Used rarely on later neo-Punic stelae. Sometimes replaced by a "rosette and crescent", where the rosette is placed above an inverted, ship-like crescent.

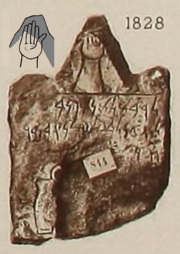

- a raised right hand, hand palm outward, seemingly picturing a blessing or prayer. Often combined with a text like "He (the god) blessed me" or "I was blessed". This symbol disappeared completely by the neo-Punic period.

- a caduceus, or messenger's staff. It basically consists of three elements, from below to top a stem, a circle, and a "U" shape. Maybe adopted from the caduceus of the Greek god Hermes, who was a guide to the Netherworld. However, in Carthage the caduceus symbol often seems to have been associated not with death but with healing, and with Esmun, the god of healing. The symbol was common in the 4th-2nd century BCE, but became ever more rare in the neo-Punic period.

- a standard. Usually used pairwise, one of the two "standards" placed at left and the other one at the right of a central picture. Often combined with the "Tanit symbol". In the 2nd century BCE it "fused" with the caduceus.

- a bottle or vase symbol, appearing in the 4th and 3rd century BCE. Attempts to interpret it have been widely varying, but there seem to be parallels with an Egyptian sign picturing the grave of Osiris, which has led to speculation that the symbol "expressed the hope of personal renewal in the afterlife".[71]

Sacrifice and dedications

Animals and other valuables were sacrificed to propitiate the gods; such sacrifices had to be done according to strict specifications,

Libations and incense also appear to have been an important part of sacrifices, based on archaeological finds.

Tophets and child sacrifice

Various Greek and Roman sources describe and criticize the Carthaginians as engaging in the practice of sacrificing children by burning.[12] Classical writers describing some version of child sacrifice to "Cronos" (Baal Hammon) include the Greek historians Diodorus Siculus and Cleitarchus, as well as the Christian apologists Tertullian and Orosius.[79][80] These descriptions were compared to those found in the Hebrew Bible describing the sacrifice of children by burning to Baal and Moloch at a place called Tophet.[79] The ancient descriptions were seemingly confirmed by the discovering of the so-called "Tophet of Salammbô" in Carthage in 1921, which contained the urns of cremated children.[81] However, modern historians and archaeologists debate the reality and extent of this practice.[82][83] Some scholars propose that all remains at the tophet were sacrificed, whereas others propose that only some were.[84]

Archaeological evidence

The specific sort of open aired sanctuary described as a Tophet in modern scholarship is unique to the Punic communities of the Western Mediterranean.[85] Over 100 tophets have been found throughout the Western Mediterranean,[86] but they are absent in Spain.[87] The largest tophet discovered was the Tophet of Salammbô at Carthage.[81] The Tophet of Salammbô seems to date to the city's founding and continued in use for at least a few decades after the city's destruction in 146 BCE.[88] No Carthaginian texts survive that would explain or describe what rituals were performed at the tophet.[87] When Carthaginian inscriptions refer to these locations, they are referred to as bt (temple or sanctuary), or qdš (shrine), not Tophets. This is the same word used for temples in general.[89][86]

As far as the archaeological evidence reveals, the typical ritual at the Tophet – which, however, shows much variation – began by the burial of a small urn containing a child's ashes, sometimes mixed with or replaced by that of an animal, after which a stele, typically dedicated to Baal Hammon and sometimes Tanit was erected. In a few occasions, a chapel was built as well.[90] Uneven burning on the bones indicate that they were burned on an open air pyre.[91] The dead children are never mentioned on the stele inscriptions, only the dedicators and that the gods had granted them some request.[92]

While tophets fell out of use after the fall of Carthage on islands formerly controlled by Carthage, in North Africa they became more common in the Roman Period.[93] In addition to infants, some of these tophets contain offerings only of goats, sheep, birds, or plants; many of the worshipers have Libyan rather than Punic names.[93] Their use appears to have declined in the second and third centuries CE.[94]

Controversy

The degree and existence of Carthaginian child sacrifice is controversial, and has been ever since the Tophet of Salammbô was discovered in 1920.[95] Some historians have proposed that the Tophet may have been a cemetery for premature or short-lived infants who died naturally and then were ritually offered.[83] The Greco-Roman authors were not eye-witnesses, contradict each other on how the children were killed, and describe children older than infants being killed as opposed to the infants found in the tophets.[81] Accounts such as Cleitarchus's, in which the baby dropped into the fire by a statue, are contradicted by the archaeological evidence.[96] There are not any mentions of child sacrifice from the Punic Wars, which are better documented than the earlier periods in which mass child sacrifice is claimed.[81] Child sacrifice may have been overemphasized for effect; after the Romans finally defeated Carthage and totally destroyed the city, they engaged in postwar propaganda to make their archenemies seem cruel and less civilized.[97] Matthew McCarty argues that, even if the Greco-Roman testimonies are inaccurate "even the most fantastical slanders rely upon a germ of fact."[96]

Many archaeologists argue that the ancient authors and the evidence of the Tophet indicates that all remains in the Tophet must have been sacrificed. Others argue that only some infants were sacrificed.[84] Paolo Xella argues that the weight of classical and biblical sources indicate that the sacrifices occurred.[98] He further argues that the number of children in the tophet is far smaller than the rate of natural infant mortality.[99] In Xella's estimation, prenatal remains at the tophet are probably those of children who were promised to be sacrificed but died before birth, but who were nevertheless offered as a sacrifice in fulfillment of a vow.[100] He concludes that the child sacrifice was probably done as a last resort and probably frequently involved the substitution of an animal for the child.[101]

See also

- Religions of the ancient Near East

- Phoenician religion

- History of the Jews in Carthage

References

- ^ a b Xella 2019, p. 273.

- ^ Xella 2019, p. 273, 281.

- ^ Christian 2013, p. 202.

- ^ a b c d Clifford 1990, p. 62.

- ^ Morstadt 2017, p. 22.

- ^ Xella 2019, p. 281.

- ^ Clifford 1990, p. 55.

- ^ a b c d e Hoyos 2021, p. 15.

- ^ Xella 2019, p. 282.

- ^ Xella 2019, pp. 275–276.

- ^ a b c Xella 2019, pp. 282–283.

- ^ a b c d e Warmington 1995, p. 453.

- ^ Miles 2010, p. 104.

- ISSN 1612-1651.

- ^ a b c Xella 2019, p. 283.

- ^ a b Xella 2019, p. 284.

- ^ Xella 2019, pp. 283–284.

- ^ a b c Clifford 1990, pp. 61–62.

- ^ a b c d Barré 1983, pp. 100–103, 125.

- ^ a b c d Hoyos 2021, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Warmington 1995, p. 454.

- ^ Fantar 2001, p. 64.

- ^ Xella 2019, pp. 281–282.

- ^ Quinn 2014.

- ^ López-Ruiz 2017.

- ISSN 0008-7912.

- ^ a b c d Xella 2019, p. 287.

- ^ Christian 2013, pp. 201–202.

- ^ Zamora 2017, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Fantar 2001, p. 62.

- ^ Morstadt 2017, p. 24.

- ^ a b c López-Bertran 2019, p. 293.

- ^ a b López-Bertran 2019, p. 296.

- ^ Gómez Bellard 2014, p. 71.

- ^ Frendo, de Trafford & Vella 2005, p. 433.

- ^ Gómez Bellard 2014, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Ben Younès & Krandel-Ben Younès 2014, pp. 149–153.

- ^ a b c d Gómez Bellard 2014, p. 72.

- ^ Gómez Bellard 2014, pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b c López-Bertran 2019, p. 300.

- ^ Sáez Romero & Belizón Aragón 2014, pp. 194.

- ^ Guirguis 2010.

- ^ García Teyssandier et al. 2016, pp. 493–530.

- ^ a b c López-Bertran 2019, p. 301.

- ^ Bernardini 2005, p. 74.

- ^ Gener Basallote et al. 2014, p. 136.

- ^ Bénichou-Safar 1975–1976, pp. 133–138.

- ^ Alatrache et al. 2001, pp. 281–297.

- ^ a b López-Bertran 2019, p. 297.

- ^ a b c d e f López-Bertran 2019, p. 303-304.

- ^ Ben Younès & Krandel-Ben Younès 2014, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Lipinski 1993, pp. 257–281.

- ^ Garbati 2010, p. 43.

- ^ Guirguis 2010, p. 38.

- ^ López-Bertran 2019, p. 304.

- ^ López-Bertran 2019, p. 303.

- ^ Spatafora 2010, p. 30.

- ^ Gómez Bellard 2014, p. 74.

- ^ López-Bertran 2019, p. 305.

- ^ López-Bertran 2019, p. 298.

- ^ Spatafora 2010, pp. 25–26.

- ^ López-Bertran 2019, p. 302.

- ^ Jiménez Flores 2002, p. 280.

- ^ a b Cooper 2005, p. 7131.

- ^ López-Bertran 2019, pp. 298–299.

- ^ López-Bertran & Garcia-Ventura 2012, pp. 393–408.

- ^ Sader, Hélène (2005). "Iron Age Funerary Stelae from Lebanon". Cuadernos de Arqueología Mediterránea. 11: 11–157. Retrieved 4 December 2022. Quote is on p.22.

- ^ a b Mendleson, Carole (2001). "Images & Symbols: on Punic Stelae from the Tophet at Carthage" (PDF). Archaeology & History in Lebanon. Spring (13): 45–50. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ISBN 9004100687.

- ^ But often interpreted as a moon and sun: Sader (2005), pp. 118-120; Mendleson (2001) p. 47.

- ^ Culican, William (1968). "Problems of Phoenicio-Punic Iconography—A Contribution" (PDF). Australian Journal of Biblical Archaeology. 1 (3): 28-57: pp. 34-45. Retrieved 4 December 2022. Quotation from p. 43.

- ^ Richey 2019, p. 234.

- ^ Xella 2013, p. 269.

- ^ Holm 2005, p. 7134.

- ^ Richey 2019, p. 231.

- ^ Richey 2019, pp. 231–232.

- ^ Miles 2010, p. 18.

- ^ Morstadt 2017, p. 26.

- ^ a b Stager & Wolff 1984.

- ^ Quinn 2011, pp. 388–389.

- ^ a b c d Hoyos 2021, p. 17.

- ^ Schwartz & Houghton 2017, p. 452.

- ^ a b Holm 2005, p. 1734.

- ^ a b Schwartz & Houghton 2017, pp. 443–444.

- ^ Xella 2013, p. 259.

- ^ a b McCarty 2019, p. 313.

- ^ a b Bonnet 2011, p. 373.

- ^ Bonnet 2011, p. 379.

- ^ Bonnet 2011, p. 374.

- ^ Bonnet 2011, pp. 378–379.

- ^ McCarty 2019, p. 315.

- ^ Bonnet 2011, pp. 383–384.

- ^ a b McCarty 2019, p. 321.

- ^ McCarty 2019, p. 322.

- ^ McCarty 2019, p. 316.

- ^ a b McCarty 2019, p. 317.

- ^ Macchiarelli & Bondioli 2012.

- ^ Xella 2013, p. 266.

- ^ Xella 2013, p. 268.

- ^ Xella 2013, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Xella 2013, p. 273.

Bibliography

- Alatrache, A.; Mahjoub, H.; Ayed, N.; Ben Younes, H. (2001). "Les fards rouges cosmétiques et rituels a base de cinabre et d'ocre de l'époque punique en Tunisie: analyse, identification, et caractérisation". International Journal of Cosmetic Science. 23 (5): 281–297. S2CID 38115452.

- Barré, Michael L. (1983). The God-list in the treaty between Hannibal and Philip V of Macedonia : a study in light of the ancient near eastern treaty tradition. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801827877.

- Bénichou-Safar, H. (1975–1976). "Les bains de resine dans les tombes puniques de Carthage". Karthago. 18: 133–138.

- Bernardini, P. (2005). "Recenti scoperte nella necropoli punica di Sulcis". Rivista di Studi Fenici. 33: 63–80.

- ISBN 978-0-89236-969-0.

- Christian, Mark A. (2013). "Phoenician Maritime Religion: Sailors, Goddess Worship, and the Grotta Regina". Die Welt des Orients. 43 (2): 179–205. JSTOR 23608854.

- Clifford, Richard J. (1990). "Phoenician Religion". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 279 (279): 55–64. S2CID 222426941.

- Cooper, Alan M. (2005). "Phoenician Religion [first edition]". In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 10 (2 ed.). Macmillan Reference. pp. 7128–7133.

- Fantar, M'Hamed Hassine (2001). "Le fait religieux à Carthage". Pallas. 56 (56): 59–66. JSTOR 43607567.

- Frendo, A. J.; de Trafford, A.; Vella, Nicholas C. (2005). "Water journeys of the dead: a glimpse into Phoenician and Punic eschatology". In Spanò Giammellaro, Antonella (ed.). Atti del V Congresso Internazionale di Studi Fenici e Punici. Palermo. pp. 427–443.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Garbati, G. (2010). "Antenati e "defunti illustri" in Sardegna: qualche considerazione sulle ideologie funerarie di età punica" (PDF). Bollettino di Archeologia Online. 1: 37–47.

- García Teyssandier, E.; Marzoli, E. D.; Cabaco Encinas, B.; Heussner, B.; Gamer-Wallert, I. (2016). "El descubrimiento de la necrópolis fenicia de Ayamonte, Huelva (siglos VIII-VII a.C.)". In Jiménez Ávila, J. (ed.). Sidereum Ana. III: El río Guadiana y Tartessos : [actas de la reunión científica]. Mérida. pp. 493–530. ISBN 9788469747889.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - Gener Basallote, J.-M.; Jurado Fresnadillo, G.; Pajuelo Sáez, J.-M.; Torres Ortiz, M (2014). "El proceso de sacralizacíon del espacio en Gadir: el yacimiento de la casa del Obispo (Cádiz). Parte I". In Botto, M. (ed.). Los Fenicios en la Bahía de Cádiz : nuevas investigaciones. Pisa: Fabrizio Serra Editore. pp. 123–155. ISBN 978-8862277648.

- Gómez Bellard, Carlos (2014). "Death among the Punics". In Quinn, Josephine Crawley; Vella, Nicholas C. (eds.). The Punic Mediterranean : Identities and Identification from Phoenician Settlement to Roman Rule. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 69–75. ISBN 9781107295193.

- Guirguis, Michele (2010). Necropoli fenicia e punica di Monte Sirai : indagini archeologiche 2005-2007. Cagliari: Ortacesus. ISBN 978-8889061-72-5.

- Holm, Tawny L. (2005). "Phoenician Religion [Further Considerations]". In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 10 (2 ed.). Macmillan Reference. pp. 7134–7135.

- Hoyos, Dexter (2021). Carthage: A Biography. Routledge. ISBN 9781138788206.

- Jiménez Flores, Ana María (2002). Pueblos y tumbas : el impacto oriental en los rituales funerarios del extremo occidente. Ecija: Gráficas Sol. ISBN 9788487165924.

- Lipinski, E. (1993). Quagebeur, J. (ed.). Ritual and sacrifice in the ancient Near East : proceedings of the international conference organized by the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven from the 17th to the 20th of April 1991. Leuven: Peeters. pp. 257–281. ISBN 9789068315806.

- López-Bertran, Mirela; Garcia-Ventura, A. (2012). "Music, Gender, and Rituals in the Ancient Mediterranean: Revisiting the Punic Evidence". World Archaeology. 44 (3): 393–408. S2CID 162345582.

- López-Ruiz, Carolina (2017). "Gargoris and Habis: An Iberian Myth and Phoenician Euhemerism". Phoenix. 71 (3–4): 265–287. .

- López-Bertran, Mirela (2019). "Funerary Ritual". In López-Ruiz, Carolina; Doak, Brian R. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean. Oxford University Press. pp. 293–309. ISBN 9780190499341.

- ISBN 978-0143121299.

- McCarty, Matthew M. (2019). "The Tophet and Infant Sacrifice". In López-Ruiz, Carolina; Doak, Brian R. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean. Oxford University Press. pp. 311–325. ISBN 9780190499341.

- Morstadt, Bärbel (2017). "Die Götterwelt Karthagos". Antike Welt. 1 (1): 22–29. JSTOR 26530885.

- Macchiarelli, R.; et al. (2012). "Bones, teeth, and estimating age of perinates: Carthaginian infant sacrifice revisited". Antiquity. 86 (333): 738–745. S2CID 162977647.

- ISBN 978-0-89236-969-0.

- ISBN 9781107295193.

- Richey, Madadh (2019). "Inscriptions". In López-Ruiz, Carolina; Doak, Brian R. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean. Oxford University Press. pp. 223–240. ISBN 9780190499341.

- Sáez Romero, A. M.; Belizón Aragón, R. (2014). "Excavaciones en la calle Hércules 12 de Cádiz. Avance resultados y primeras propuestas acerca de la posible necrópolis fenicia insular de Gadir". In Botto, M. (ed.). Los Fenicios en la Bahía de Cádiz : nuevas investigaciones. Pisa: Fabrizio Serra Editore. pp. 181–200. ISBN 978-8862277648.

- Schwartz, J.H.; et al. (2017). "Two tales of one city: data, inference and Carthaginian infant sacrifice". Antiquity. 91 (356): 442–454. S2CID 164242410.

- Spatafora, F. (2010). "Ritualità e simbolismo nella necropoli punica di Palermo". In Dolce, R. (ed.). Atti della giornata di studi in onore di Antonella Spanò : Facoltà di lettere e filosofia, 30 maggio 2008. Palermo: Università di Palermo. Dipartimento di beni culturali. pp. 25–26. ISBN 9788890520808.

- Stager, Lawrence E.; Wolff, Samuel R. (January–February 1984). "Child Sacrifice at Carthage: Religious Rite or Population Control?" (PDF). Biblical Archaeology Review.[dead link]

- Warmington, B. H. (1995). "The Carthaginian Period". In Mokhtar, G. (ed.). General history of Africa. Vol. 2, Ancient civilizations of Africa. London: Heinemann. pp. 441–464.

- Xella, Paolo (2013). ""Tophet": an Overall Interpretation". In Xella, P. (ed.). The Tophet in the Ancient Mediterranean. Essedue. pp. 259–281.

- Xella, Paolo (2019). "Religion". In López-Ruiz, Carolina; Doak, Brian R. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean. pp. 273–292. ISBN 978-0-19-049934-1.

- Ben Younès, Habib; Krandel-Ben Younès, Alia (2014). "Punic identity in North Africa: the funerary world". In Quinn, Josephine Crawley; Vella, Nicholas C. (eds.). The Punic Mediterranean : Identities and Identification from Phoenician Settlement to Roman Rule. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 148–168. ISBN 9781107295193.

- Zamora, José Á. (2017). "The miqim elim: Epigraphic Evidence for a Specialist in the Phoenician-Punic Cult". Revista di Studi Fenici. 45: 65–85.

External links

Media related to Punic religion at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Punic religion at Wikimedia Commons