Reality

Reality is the sum or aggregate of all that is real or existent within the universe, as opposed to that which is only imaginary, nonexistent or nonactual. The term is also used to refer to the ontological status of things, indicating their existence.[1] In physical terms, reality is the totality of a system, known and unknown.[2]

Philosophical questions about the nature of reality or existence or being are considered under the

World views

World views and theories

A common colloquial usage would have reality mean "perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes toward reality", as in "My reality is not your reality." This is often used just as a colloquialism indicating that the parties to a conversation agree, or should agree, not to quibble over deeply different conceptions of what is real. For example, in a religious discussion between friends, one might say (attempting humor), "You might disagree, but in my reality, everyone goes to heaven."

Reality can be defined in a way that links it to worldviews or parts of them (conceptual frameworks): Reality is the totality of all things, structures (actual and conceptual), events (past and present) and phenomena, whether observable or not. It is what a world view (whether it be based on individual or shared human experience) ultimately attempts to describe or map.

Certain ideas from physics, philosophy, sociology, literary criticism, and other fields shape various theories of reality. One such theory is that there simply and literally is no reality beyond the perceptions or beliefs we each have about reality.[citation needed] Such attitudes are summarized in popular statements, such as "Perception is reality" or "Life is how you perceive reality" or "reality is what you can get away with" (Robert Anton Wilson), and they indicate anti-realism – that is, the view that there is no objective reality, whether acknowledged explicitly or not.

Many of the concepts of science and philosophy are often defined culturally and socially. This idea was elaborated by Thomas Kuhn in his book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962). The Social Construction of Reality, a book about the sociology of knowledge written by Peter L. Berger and Thomas Luckmann, was published in 1966. It explained how knowledge is acquired and used for the comprehension of reality. Out of all the realities, the reality of everyday life is the most important one since our consciousness requires us to be completely aware and attentive to the experience of everyday life.

Related concepts

A priori and a posteriori

Potentiality and actuality

In

The concept of potentiality, in this context, generally refers to any "possibility" that a thing can be said to have. Aristotle did not consider all possibilities the same, and emphasized the importance of those that become real of their own accord when conditions are right and nothing stops them.[9]

Actuality, in contrast to potentiality, is the motion, change or activity that represents an exercise or fulfillment of a possibility, when a possibility becomes real in the fullest sense.[10]Belief

A belief is a subjective attitude that a proposition is true or a state of affairs is the case. A subjective attitude is a mental state of having some stance, take, or opinion about something.[11] In epistemology, philosophers use the term "belief" to refer to attitudes about the world which can be either true or false.[12] To believe something is to take it to be true; for instance, to believe that snow is white is comparable to accepting the truth of the proposition "snow is white". However, holding a belief does not require active introspection. For example, few individuals carefully consider whether or not the sun will rise tomorrow, simply assuming that it will. Moreover, beliefs need not be occurrent (e.g. a person actively thinking "snow is white"), but can instead be dispositional (e.g. a person who if asked about the color of snow would assert "snow is white").[12]

There are various ways that contemporary

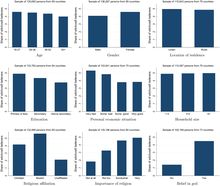

Belief studies

Western philosophy

Philosophy addresses two different aspects of the topic of reality: the nature of reality itself, and the relationship between the mind (as well as language and culture) and reality.

On the one hand,

On the other hand, particularly in discussions of

Realism

The view that there is a reality independent of any beliefs, perceptions, etc., is called realism. More specifically, philosophers are given to speaking about "realism about" this and that, such as realism about universals or realism about the external world. Generally, where one can identify any class of object, the existence or essential characteristics of which is said not to depend on perceptions, beliefs, language, or any other human artifact, one can speak of "realism about" that object.

A

Anti-realism

One can also speak of anti-realism about the same objects.

Being

The nature of

Explanations for the existence of something rather than nothing

Perception

The question of

Abstract objects and mathematics

The status of abstract entities, particularly numbers, is a topic of discussion in mathematics.

In the

Anti-realist stances include

Some approaches are selectively realistic about some mathematical objects but not others.

The traditional debate has focused on whether an abstract (immaterial, intelligible) realm of numbers has existed in addition to the physical (sensible, concrete) world. A recent development is the mathematical universe hypothesis, the theory that only a mathematical world exists, with the finite, physical world being an illusion within it.

An extreme form of realism about mathematics is the

Properties

The problem of universals is an ancient problem in

The realist school claims that universals are real – they exist and are distinct from the particulars that instantiate them. There are various forms of realism. Two major forms are

Nominalism and conceptualism are the main forms of anti-realism about universals.

Time and space

A traditional realist position in ontology is that time and space have existence apart from the human mind. Idealists deny or doubt the existence of objects independent of the mind. Some anti-realists whose ontological position is that objects outside the mind do exist, nevertheless doubt the independent existence of time and space.

Idealist writers such as J. M. E. McTaggart in The Unreality of Time have argued that time is an illusion.

As well as differing about the reality of time as a whole, metaphysical theories of time can differ in their ascriptions of reality to the past, present and future separately.

- Presentismholds that the past and future are unreal, and only an ever-changing present is real.

- The block universe theory, also known as Eternalism, holds that past, present and future are all real, but the passage of time is an illusion. It is often said to have a scientific basis in relativity.

- The growing block universe theory holds that past and present are real, but the future is not.

Time, and the related concepts of process and

Possible worlds

The term "

Theories of everything (TOE) and philosophy

The philosophical implications of a physical TOE are frequently debated. For example, if philosophical physicalism is true, a physical TOE will coincide with a philosophical theory of everything.

The

were later systems.Other philosophers do not believe its techniques can aim so high. Some scientists think a more mathematical approach than philosophy is needed for a TOE, for instance Stephen Hawking wrote in A Brief History of Time that even if we had a TOE, it would necessarily be a set of equations. He wrote, "What is it that breathes fire into the equations and makes a universe for them to describe?"[34]

Phenomenology

On a much broader and more subjective level,[specify] private experiences, curiosity, inquiry, and the selectivity involved in personal interpretation of events shapes reality as seen by one and only one person[35] and hence is called phenomenological. While this form of reality might be common to others as well, it could at times also be so unique to oneself as to never be experienced or agreed upon by anyone else. Much of the kind of experience deemed spiritual occurs on this level of reality.

Phenomenology is a

The word phenomenology comes from the

Husserl's conception of phenomenology has also been criticised and developed by his student and assistant

Skeptical hypotheses

Skeptical hypotheses in philosophy suggest that reality could be very different from what we think it is; or at least that we cannot prove it is not. Examples include:

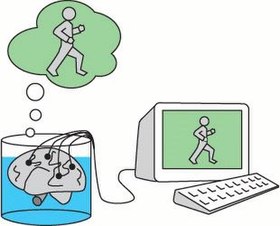

- The "Brain in a vat" hypothesis is cast in scientific terms. It supposes that one might be a disembodied brain kept alive in a vat, and fed false sensory signals. This hypothesis is related to the Matrix hypothesis below.

- The "Dream argument" of Descartes and Zhuangzi supposes reality to be indistinguishable from a dream.

- Descartes' Evil demon is a being "as clever and deceitful as he is powerful, who has directed his entire effort to misleading me."

- The Last Thursdayism) suggests that the world was created recently together with records and traces indicating a greater age.

- Diminished reality refers to artificially diminished reality, not due to limitations of sensory systems but via artificial filters[38]

- Simulated reality hypothesis suggest that we might be inside a computer simulation or virtual reality. Related hypotheses may also involve simulations with signals that allow the inhabitant species in virtual or simulated reality to perceive the external reality.

Non-western ancient philosophy and religion

Jain philosophy

Jain philosophy postulates that seven tattva (truths or fundamental principles) constitute reality.[39] These seven tattva are:[40]

- soulwhich is characterized by consciousness.

- Ajīva – The non-soul.

- Asrava – Influx of karma.

- Bandha – The bondage of karma.

- Samvara – Obstruction of the inflow of karmic matter into the soul.

- Nirjara – Shedding of karmas.

- Moksha – Liberation or Salvation, i.e. the complete annihilation of all karmic matter (bound with any particular soul).

Physical sciences

Scientific realism

Scientific realism is, at the most general level, the view that the world (the universe) described by science (perhaps ideal science) is the real world, as it is, independent of what we might take it to be. Within philosophy of science, it is often framed as an answer to the question "how is the success of science to be explained?" The debate over what the success of science involves centers primarily on the status of entities that are not directly observable discussed by scientific theories. Generally, those who are scientific realists state that one can make reliable claims about these entities (viz., that they have the same ontological status) as directly observable entities, as opposed to instrumentalism. The most used and studied scientific theories today state more or less the truth.

Realism and locality in physics

Realism in the sense used by physicists does not equate to realism in metaphysics.[41] The latter is the claim that the world is mind-independent: that even if the results of a measurement do not pre-exist the act of measurement, that does not require that they are the creation of the observer. Furthermore, a mind-independent property does not have to be the value of some physical variable such as position or momentum. A property can be dispositional (or potential), i.e. it can be a tendency: in the way that glass objects tend to break, or are disposed to break, even if they do not actually break. Likewise, the mind-independent properties of quantum systems could consist of a tendency to respond to particular measurements with particular values with ascertainable probability.[42] Such an ontology would be metaphysically realistic, without being realistic in the physicist's sense of "local realism" (which would require that a single value be produced with certainty).

A closely related term is counterfactual definiteness (CFD), used to refer to the claim that one can meaningfully speak of the definiteness of results of measurements that have not been performed (i.e. the ability to assume the existence of objects, and properties of objects, even when they have not been measured).

The transition from "possible" to "actual" is a major topic of

Role of "observation" in quantum mechanics

The quantum mind–body problem refers to the philosophical discussions of the mind–body problem in the context of quantum mechanics. Since quantum mechanics involves quantum superpositions, which are not perceived by observers, some interpretations of quantum mechanics place conscious observers in a special position.

The founders of quantum mechanics debated the role of the observer, and of them, Wolfgang Pauli and Werner Heisenberg believed that it was the observer that produced collapse. This point of view, which was never fully endorsed by Niels Bohr, was denounced as mystical and anti-scientific by Albert Einstein. Pauli accepted the term, and described quantum mechanics as lucid mysticism.[44]

Heisenberg and Bohr always described quantum mechanics in logical positivist terms. Bohr also took an active interest in the philosophical implications of quantum theories such as his complementarity, for example.[45] He believed quantum theory offers a complete description of nature, albeit one that is simply ill-suited for everyday experiences – which are better described by classical mechanics and probability. Bohr never specified a demarcation line above which objects cease to be quantum and become classical. He believed that it was not a question of physics, but one of philosophy.

Multiverse

The

The structure of the multiverse, the nature of each universe within it and the relationship between the various constituent universes, depend on the specific multiverse hypothesis considered. Multiverses have been hypothesized in cosmology, physics, astronomy, religion, philosophy, transpersonal psychology and fiction, particularly in science fiction and fantasy. In these contexts, parallel universes are also called "alternative universes", "quantum universes", "interpenetrating dimensions", "parallel dimensions", "parallel worlds", "alternative realities", "alternative timelines", and "dimensional planes", among others.

Anthropic principle

Personal and collective reality

Each individual has a different view of reality, with different memories and personal history, knowledge, personality traits and experience.[52] This system, mostly referring to the human brain, affects cognition and behavior and into this complex new knowledge, memories,[53] information, thoughts and experiences are continuously integrated.[54][additional citation(s) needed] The connectome – neural networks/wirings in brains – is thought to be a key factor in human variability in terms of cognition or the way we perceive the world (as a context) and related features or processes.[55][56][57] Sensemaking is the process by which people give meaning to their experiences and make sense of the world they live in. Personal identity is relating to questions like how a unique individual is persisting through time.

Sensemaking and determination of reality also occurs collectively, which is investigated in social epistemology and related approaches. From the collective intelligence perspective, the intelligence of the individual human (and potentially AI entities) is substantially limited and advanced intelligence emerges when multiple entities collaborate over time.[58][additional citation(s) needed] Collective memory is an important component of the social construction of reality[59] and communication and communication-related systems, such as media systems, may also be major components .

Philosophy of perception raises questions based on the evolutionary history of humans' perceptual apparatuses, particularly or especially individuals'

Scientific theories of everything

A

Initially, the term "theory of everything" was used with an ironic connotation to refer to various overgeneralized theories. For example, a great-grandfather of

Current candidates for a theory of everything include

Technology

Media

Media – such as news media, social media, websites including Wikipedia,[64] and fiction[65] – shape individuals' and society's perception of reality (including as part of belief and attitude formation)[65] and are partly used intentionally as means to learn about reality. Various technologies have changed society's relationship with reality such as the advent of radio and TV technologies.

Research investigates interrelations and effects, for example aspects in the social construction of reality.[66] A major component of this shaping and representation of perceived reality is agenda, selection and prioritization – not only (or primarily) the quality, tone and types of content – which influences, for instance, the public agenda.[67][68] Disproportional news attention for low-probability incidents – such as high-consequence accidents – can distort audiences' risk perceptions with harmful consequences.[69] Various biases such as false balance, public attention dependence reactions like sensationalism and domination by "current events",[70] as well as various interest-driven uses of media such as marketing can also have major impacts on the perception of reality. Time-use studies found that e.g. in 2018 the average U.S. American "spent around eleven hours every day looking at screens".[71]

Filter bubbles and echo chambers

Virtual reality and cyberspace

Virtual reality (VR) is a computer-simulated environment that can simulate physical presence in places in the real world, as well as in imaginary worlds.

The area between the two extremes, where both the real and the virtual are mixed, is the so-called

"RL" in internet culture

On the Internet, "

See also

Notes

- ^ "reality | Definition of reality in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on September 26, 2016. Retrieved 2017-10-28.

- S2CID 126411165.

- ^ Funk, Ken (2001-03-21). "What is a Worldview?". Retrieved 2019-12-10.

- ISBN 978-0-292-76569-6.

- associationist philosophers have contended that mathematics comes from experience and is not a form of any a priori knowledge (Macleod 2016)

- ^ Galen Strawson has stated that an a priori argument is one in which "you can see that it is true just lying on your couch. You don't have to get up off your couch and go outside and examine the way things are in the physical world. You don't have to do any science." (Sommers 2003)

- ^ dynamis–energeia, translated into Latin as potentia–actualitas (earlier also possibilitas–efficacia). Giorgio Agamben, Opus Dei: An Archaeology of Duty (2013), p. 46.

- ^ Sachs (2005)

- ^ Sachs (1999, p. lvii).

- ^ Durrant (1993, p. 206)

- ^ Primmer, Justin (2018), "Belief", in Primmer, Justin (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford, CA: The Metaphysics Research Lab, archived from the original on 15 November 2019, retrieved 2008-09-19

- ^ a b c d e "Belief". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ "Formal Representations of Belief". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 11 July 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ PMID 36417350.

- ^ "Witchcraft beliefs are widespread, highly variable around the world". Public Library of Science via phys.org. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- S2CID 245916820.

- ^ Clifford, Catherine. "Americans don't think other Americans care about climate change as much as they do". CNBC. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- PMID 35999211.

- PMID 35418909.

- PMID 34815421.

- ^ "Principles of Nature and Grace", 1714, Article 7.

- ^ "Not how the world is, is the mystical, but that it is", Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus 6.44

- ^ "Why are there beings at all, and why not rather nothing? That is the question." What is Metaphysics? (1929), p. 110, Heidegger.

- Introduction to Metaphysics, Yale University Press, New Haven and London (1959), pp. 7–8.

- ^ "The Fundamental Question". www.hedweb.com. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ISBN 978-3644045118.

- ^ Lehar, Steve. (2000). The Function of Conscious Experience: An Analogical Paradigm of Perception and Behavior Archived 2015-10-21 at the Wayback Machine, Consciousness and Cognition.

- ^ Lehar, Steve. (2000). Naïve Realism in Contemporary Philosophy Archived 2012-08-11 at the Wayback Machine, The Function of Conscious Experience.

- ^ Lehar, Steve. Representationalism Archived 2012-09-05 at the Wayback Machine

- S2CID 9890455.

- ^ Tegmark (1998), p. 1.

- ^ Loux, Michael J. (2001). "The Problem of Universals" in Metaphysics: Contemporary Readings, Michael J. Loux (ed.), N.Y.: Routledge, pp. 3–13, [4]

- ^ Price, H. H. (1953). "Universals and Resemblance", Ch. 1 of Thinking and Experience, Hutchinson's University Library, among others, sometimes uses such Latin terms

- ^ as quoted in [Artigas, The Mind of the Universe, p.123]

- ^ Present-time consciousness Francisco J. Varela Journal of Consciousness Studies 6 (2-3):111-140 (1999)

- ISBN 1-55753-050-5.

- ISBN 0-8101-1805-X.

- S2CID 21053932.

- ^ Jain 1992, p. 6.

- ^ Jain 1992, p. 7.

- S2CID 15072850.

- ^ Thompson, Ian. "Generative Science". www.generativescience.org.

- ^ "Local realism and the crucial experiment". bendov.info.

- ^ John Honner (2005). "Niels Bohr and the Mysticism of Nature". Zygon: Journal of Religion & Science. 17–3: 243–253.

- S2CID 55537196.

- ^ Michael Esfeld, (1999), Essay Review: Wigner's View of Physical Reality, published in Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 30B, pp. 145–154, Elsevier Science Ltd.

- OED's new 2003 entry for "multiverse": "1895 W. JAMES in Internat. Jrnl. Ethics 6 10 Visible nature is all plasticity and indifference, a multiverse, as one might call it, and not a universe."

- ^ Bostrom, Nick (2008). "Where are they? Why I hope the search for extraterrestrial life finds nothing" (PDF). Technology Review. 2008: 72–77. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Bostrom, Nick (9 February 2020). "Was the Universe made for us?". anthropic-principle.com.

The data we collect about the Universe is filtered not only by our instruments' limitations, but also by the precondition that somebody be there to 'have' the data yielded by the instruments (and to build the instruments in the first place).

- ^ James Schombert. "Anthropic principle". Department of Physics at University of Oregon. Archived from the original on 2012-04-28. Retrieved 2012-04-26.

- S2CID 149797460.

- PMID 32179822.

- ^ "Understanding reality through algorithms". MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ^ Popova, Maria (28 March 2012). "The Connectome: A New Way To Think About What Makes You You". The Atlantic. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ISBN 978-0547508177.

- ^ "Quest for the connectome: scientists investigate ways of mapping the brain". The Guardian. 7 May 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- S2CID 220050285.

- S2CID 145106025.

- S2CID 4400770.

- ^ Weinberg (1993)

- PMID 11875539.

- S2CID 4344940.

- S2CID 238657838.

- ^ a b Prentice, D.; Gerrig, R. (1999). "Exploring the boundary between fiction and reality". In S. Chaiken; Y. Trope (eds.). Dual-process theories in social psychology. The Guilford Press. pp. 529–546.

- JSTOR 2083459.

- doi:10.1086/267990.

- ISBN 978-0203877111.

- .

- ^ "How the news took over reality". The Guardian. 3 May 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ^ Gorvett, Zaria. "How the news changes the way we think and behave". BBC. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ^ Technopedia, Definition – What does Filter Bubble mean? Archived 2017-10-10 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved October 10, 2017, "....A filter bubble is the intellectual isolation, that can occur when websites make use of algorithms to selectively assume the information a user would want to see, and then give information to the user according to this assumption ... A filter bubble, therefore, can cause users to get significantly less contact with contradicting viewpoints, causing the user to become intellectually isolated...."

- S2CID 14970635.

- ^ Huffington Post, The Huffington Post "Are Filter-bubbles Shrinking Our Minds?" Archived 2016-11-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Encrypt, Search (2019-02-26). "What Are Filter Bubbles & How To Avoid Them". Search Encrypt Blog. Archived from the original on 2019-02-25. Retrieved 2019-03-19.

- ^ The term cyber-balkanization (sometimes with a hyphen) is a hybrid of cyber, relating to the internet, and Balkanization, referring to that region of Europe that was historically subdivided by languages, religions and cultures; the term was coined in a paper by MIT researchers Van Alstyne and Brynjolfsson.

- ^ Van Alstyne, Marshall; Brynjolfsson, Erik (March 1997) [Copyright 1996]. "Electronic Communities: Global Village or Cyberbalkans?" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-04-05. Retrieved 2017-09-24.

- S2CID 62546078.

- ^ Alex Pham; Jon Healey (September 24, 2005). "Systems hope to tell you what you'd like: 'Preference engines' guide users through the flood of content". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved December 4, 2015.

...if recommenders were perfect, I can have the option of talking to only people who are just like me....Cyber-balkanization, as Brynjolfsson coined the scenario, is not an inevitable effect of recommendation tools.

- ^ Weisberg, Jacob (June 10, 2011). "Bubble Trouble: Is Web personalization turning us into solipsistic twits?". Slate. Archived from the original on June 12, 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ Lazar, Shira (June 1, 2011). "Algorithms and the Filter Bubble Ruining Your Online Experience?". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on April 13, 2016. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

a filter bubble is the figurative sphere surrounding you as you search the Internet.

- ^ Milgram, Paul; H. Takemura; A. Utsumi; F. Kishino (1994). "Augmented Reality: A class of displays on the reality-virtuality continuum" (PDF). Proceedings of Telemanipulator and Telepresence Technologies. pp. 2351–34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-10-04. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- ^ "IRL – Definition by AcronymFinder". www.acronymfinder.com.

- ISBN 0-7619-6510-6.

References

- Berger, Peter L.; Luckmann, Thomas (1966). The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. New York: Anchor Books. pp. 21–22.

- Durrant, Michael (1993). Aristotle's De Anima in Focus. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-05340-2.

- Jain, S. A. (1992). Reality. Jwalamalini Trust.

Not in Copyright

Alt URL - Macleod, Christopher (25 August 2016). "John Stuart Mill". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2020 ed.) – via Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- Sachs, Joe (1999). Aristotle's Metaphysics, a New Translation. Santa Fe, New Mexico: Green Lion Books. ISBN 1-888009-03-9.

- Sachs, Joe (2005). "Aristotle: Motion and its Place in Nature". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Sommers, Tamler (March 2003). Jarman, Casey (ed.). "Galen Strawson (interview)". Believer Magazine. 1 (1). San Francisco, CA: McSweeney's McMullens. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

Further reading

- George Musser, "Virtual Reality: How close can physics bring us to a truly fundamental understanding of the world?", Scientific American, vol. 321, no. 3 (September 2019), pp. 30–35.

- "Physics is ... the bedrock of the broader search for truth.... Yet [physicists] sometimes seem to be struck by a collective impostor syndrome.... Truth can be elusive even in the best-established theories. Quantum mechanics is as well tested a theory as can be, yet its interpretation remains inscrutable. [p. 30.] The deeper physicists dive into reality, the more reality seems to evaporate." [p. 34.]