Mind

The mind (adjective form: mental) is that which

The exact nature of the mind is disputed. Traditionally, minds were understood as substances, but contemporary philosophers tend to see them as collections of properties or capacities. There is a lengthy tradition in philosophy, religion, psychology, and cognitive science exploring what constitutes a mind, what its distinguishing properties are, and whether humans are the only beings that have minds.

Mind, or mentality, is usually contrasted with body, matter, or physicality. The issue of the nature of this contrast and specifically the relation between mind and brain is called the

Different cultural and religious traditions often use different concepts of mind, resulting in different answers to these questions. Some see mind as a property exclusive to humans, whereas others ascribe properties of mind to non-living entities (e.g.,

Psychologists such as Freud and James and computer scientists such as Turing developed influential theories about the nature of the mind. The possibility of nonbiological minds is explored in the field of artificial intelligence, which works closely with cybernetics and information theory to understand the ways in which information processing by nonbiological machines is comparable to or different from mental phenomena in the human mind.[7] The mind is also sometimes portrayed as a stream of consciousness, where sense impressions and mental phenomena are constantly changing.[8][9]

Etymology

The original meaning of Old English gemynd was the faculty of memory, not of thought in general.[10] Hence call to mind, come to mind, keep in mind, to have mind of, etc. The word retains this sense in Scotland.[11] Old English had other words to express "mind", such as hyge "mind, spirit".[12]

The meaning of "memory" is shared with

The generalization of mind to include all mental faculties, thought, volition, feeling and memory, gradually develops over the 14th and 15th centuries.[13]

Definitions

The mind is often understood as a faculty that manifests itself in

Despite this agreement, there is still a lot of difference of opinion concerning what the exact nature of mind is and various competing characterizations have been proposed, sometimes referred to as theories of mind.[1][17][a] Philosophical definitions of mind usually proceed not just by listing various types of phenomena belonging to the mind but by searching the "mark of the mental": a feature that is shared by all mental states and only by mental states.[15][14] Epistemic approaches define mental states in terms of the privileged epistemic access the subject has to these states. This is often combined with a consciousness-based approach, which emphasizes the primacy of consciousness in relation to mind. Intentionality-based approaches, on the other hand, see the power of minds to refer to objects and represent the world as being a certain way as the mark of the mental. According to behaviorism, whether an entity has a mind only depends on how it behaves in response to external stimuli while functionalism defines mental states in terms of the causal roles they play. The differences between these diverse approaches are substantial since they result in very different answers to questions like whether animals or computers have minds.[1][15][14]

There is a great variety of mental states. They fall into categories like sensory and non-sensory or conscious and unconscious.[18][14] Various of the definitions listed above excel for states from one category but struggle to account for why states from another category are also part of the mind. This has led some theorists to doubt that there is a mark of the mental. So maybe the term "mind" just refers to a cluster of loosely related ideas that do not share one unifying feature.[14][15][16] Some theorists have responded to this by narrowing their definitions of mind to "higher" intellectual faculties, like thinking, reasoning and memory. Others try to be as inclusive as possible regarding "lower" intellectual faculties, like sensing and emotion.[19]

In popular usage, mind is frequently synonymous with thought: the private conversation with ourselves that we carry on "inside our heads".[20] Thus we "make up our minds", "change our minds" or are "of two minds" about something. One of the key attributes of the mind in this sense is that it is a private sphere to which no one but the owner has access. No one else can "know our mind". They can only interpret what we consciously or unconsciously communicate.[21]

Epistemic and consciousness-based approaches

One way to respond to this worry is to ascribe a privileged status to conscious mental states. On such a consciousness-based approach, conscious mental states are non-derivative constituents of the mind while unconscious states somehow depend on their conscious counterparts for their existence.[15][22][23] An influential example of this position is due to John Searle, who holds that unconscious mental states have to be accessible to consciousness to count as "mental" at all.[24] They can be understood as dispositions to bring about conscious states.[25] This position denies that the so-called "deep unconscious", i.e. mental contents inaccessible to consciousness, exists.[26] Another problem for consciousness-based approaches, besides the issue of accounting for the unconscious mind, is to elucidate the nature of consciousness itself. Consciousness-based approaches are usually interested in phenomenal consciousness, i.e. in qualitative experience, rather than access consciousness, which refers to information being available for reasoning and guiding behavior.[15][27][28] Conscious mental states are normally characterized as qualitative and subjective, i.e. that there is something it is like for a subject to be in these states. Opponents of consciousness-based approaches often point out that despite these attempts, it is still very unclear what the term "phenomenal consciousness" is supposed to mean.[15] This is important because not much would be gained theoretically by defining one ill-understood term in terms of another. Another objection to this type of approach is to deny that the conscious mind has a privileged status in relation to the unconscious mind, for example, by insisting that the deep unconscious exists.[23][26]

Intentionality-based approaches

Intentionality-based approaches see

Behaviorism and functionalism

Behaviorist definitions characterize mental states as dispositions to engage in certain publicly observable behavior as a reaction to particular external stimuli.[37][38] On this view, to ascribe a belief to someone is to describe the tendency of this person to behave in certain ways. Such an ascription does not involve any claims about the internal states of this person, it only talks about behavioral tendencies.[38] A strong motivation for such a position comes from empiricist considerations stressing the importance of observation and the lack thereof in the case of private internal mental states. This is sometimes combined with the thesis that we could not even learn how to use mental terms without reference to the behavior associated with them.[38] One problem for behaviorism is that the same entity often behaves differently despite being in the same situation as before. This suggests that explanation needs to make reference to the internal states of the entity that mediate the link between stimulus and response.[39][40] This problem is avoided by functionalist approaches, which define mental states through their causal roles but allow both external and internal events in their causal network.[41][42][16] On this view, the definition of pain-state may include aspects such as being in a state that "tends to be caused by bodily injury, to produce the belief that something is wrong with the body and ... to cause wincing or moaning".[43][18]

One important aspect of both behaviorist and functionalist approaches is that, according to them, the mind is

One problem for all of these views is that they seem to be unable to account for the phenomenal consciousness of the mind emphasized by consciousness-based approaches.[18] It may be true that pains are caused by bodily injuries and themselves produce certain beliefs and moaning behavior. But the causal profile of pain remains silent on the intrinsic unpleasantness of the painful experience itself. Some states that are not painful to the subject at all may even fit these characterizations.[18][43]

Externalism

Theories under the umbrella of externalism emphasize the mind's dependency on the environment. According to this view, mental states and their contents are at least partially by external circumstances.[46][47] For example, some forms of content externalism hold that it can depend on external circumstances whether a belief refers to one object or another.[48][49] The extended mind thesis states that external circumstances not only affect the mind but are part of it.[50][51] The closely related view of enactivism holds that mental processes involve an interaction between organism and environment.[52][53]

Forms

Functions and processes

The mind encompasses many functions and processes, including

Memory is the mechanism of storing and retrieving information.[56] Episodic memory handles information about specific past events in one's life and makes this information available in the present. When a person remembers what they had for dinner yesterday, they employ episodic memory. Semantic memory handles general knowledge about the world that is not tied to any specific episodes. When a person recalls that the capital of Japan is Tokyo, they usually access this general information without recalling the specific instance when they learned it. Procedural memory is memory of how to do things, such as riding a bicycle or playing a musical instrument.[57] Another distinction is between short-term memory, which holds information for brief periods, usually with the purpose of completing specific cognitive tasks, and long-term memory, which can store information indefinitely.[58]

Thinking involves the processing of information and the manipulation of

Imagination is a creative process of internally generating mental images. Unlike perception, it does not directly depend on the stimulation of sensory organs. Similar to

Motivation is an internal state that propels individuals to initiate, continue, or terminate goal-directed behavior. It is responsible for the formation of

Attention is an aspect of other mental processes in which mental resources like awareness are directed towards certain features of experience and away from others. This happens when a driver focuses on the traffic while ignoring billboards on the side of the road. Attention can be controlled voluntarily in the pursuit of specific goals but can also occur involuntarily when a strong stimulus captures a person's attention.[67] Attention is relevant to learning, which is the ability of the mind to acquire new information and permanently modify its understanding and behavioral patterns. Individuals learn by undergoing experiences, which helps them adapt to the environment.[68]

Faculties and modules

Traditionally, the mind was subdivided into mental faculties understood as capacities to perform certain functions or bring about certain processes.[69] An influential subdivision in the history of philosophy was between the faculties of intellect and will.[70] The intellect encompasses mental phenomena aimed at understanding the world and determining what to believe or what is true; the will has a practical orientation focused on desire, decision-making, action, and what is good.[71] The exact number and nature of the mental faculties are disputed and more fine-grained subdivisions have been proposed, such as dividing the intellect into the faculties of understanding and judgment or adding sensibility as an additional faculty responsible for sensory impressions.[72][b]

In contrast to the traditional view, more recent approaches analyze the mind in terms of

Conscious and unconscious

An influential distinction is between conscious and unconscious mental processes. Consciousness is the awareness of external and internal circumstances. It encompasses a wide variety of states, such as perception, thinking, fantasizing, dreaming, and

Unconscious or nonconscious mental processes operate without the individual's awareness but can still influence mental phenomena on the level of thought, feeling, and action. Some theorists distinguish between preconscious, subconscious, and unconscious states depending on their accessibility to conscious awareness.

Other categories of mental phenomena

A mental state or process is rational if it is based on good reasons. For example, a belief is rational if it relies on strong supporting evidence and a decision is rational if it follows careful deliberation of all the relevant factors and outcomes. Mental states are irrational if they are not based on good reasons, such as beliefs caused by faulty reasoning, superstition, or cognitive biases, and decisions that give into temptations instead of following one's best judgment.[86] Mental states that fall outside the domain of rational evaluation are arational rather than irrational. There is controversy regarding which mental phenomena lie outside this domain; suggested examples include sensory impressions, feelings, desires, and involuntary responses.[87]

Another contrast is between dispositional and occurrent mental states. A dispositional state is a power that is not exercised. If a person believes that cats have whiskers but does not think about this fact, it is a dispositional belief. By activating the belief to consciously think about it or use it in other cognitive processes, it becomes occurrent until it is no longer actively considered or used. The great majority of a person's beliefs are dispositional most of the time.[88]

Relation to matter

Mind–body problem

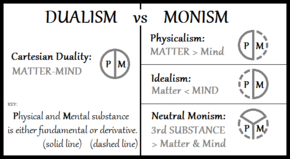

The mind–body problem is the difficulty of providing a general explanation of the relationship between mind and body, for example, of the link between thoughts and brain processes. Despite their different characteristics, mind and body interact with each other, like when a bodily change causes mental discomfort or when a limb moves because of an

The monist view most influential in contemporary philosophy is

The hard problem of consciousness is a central aspect of the mind–body problem: it is the challenge of explaining how physical states can give rise to conscious experience. Its main difficulty lies in the subjective and qualitative nature of consciousness, which is unlike typical physical processes. The hard problem of consciousness contrasts with the "easy problems" of explaining how certain aspects of consciousness function, such as perception, memory, or learning.[104]

Brain areas and processes

Another approach to the relation between mind and matter uses empirical observation to study how the brain works and which brain areas and processes are associated with specific mental phenomena.

The primary operation of many of the main mental phenomena is located in specific areas of the forebrain. The

The close interrelation of brain processes and the mind is seen by the effect that physical changes of the brain have on the mind. For instance, the consumption of

Development

Evolution

The mind has a long evolutionary history starting with the development of the nervous system and the brain.[117] While it is generally accepted today that mind is not exclusive to humans and various non-human animals have some form of mind, there is no consensus at which point exactly the mind emerged.[118] The evolution of mind is usually explained in terms of natural selection: genetic variations responsible for new or improved mental capacities, like better perception or social dispositions, have an increased chance of being passed on to future generations if they are beneficial to survival and reproduction.[119]

Minimal forms of information processing are already found in the earliest forms of life 4 to 3.5 billion years ago, like the abilities of

The size of the brain relative to the body further increased with the development of

Individual

Besides the development of mind in general in the course of history, there is also the

Numerous research showed that even embryos demonstrated behavior that could be attributed to ecological learning.[133][134][135][136][137][138][139] At this pre-reflex stage, the embryonal nervous system replicates maternal dynamics at the cellular level for the appropriate neural tissue development – solving, in such a manner, the morphology problem and the binding problem.

Early childhood is marked by rapid developments as infants learn voluntary control over their bodies and interact with their environment on a basic level. Typically after about one year, this covers abilities like walking, recognizing familiar faces, and producing individual words.[140] On the emotional and social levels, they develop attachments with their primary caretakers and express emotions ranging from joy to anger, fear, and surprise.[141] An influential theory by Jean Piaget divides the cognitive development of children into four stages. The sensorimotor stage from birth until two years is concerned with sensory impressions and motor activities while learning that objects remain in existence even when not observed. In the preoperational stage until seven years, children learn to interpret and use symbols in an intuitive manner. They start employing logical reasoning to physical objects in the concrete operational stage until eleven years and extend this capacity in the following formal operational stage to abstract ideas as well as probabilities and possibilities.[142] Other important processes shaping the mind in this period are socialization and enculturation, at first through primary caretakers and later through peers and the schooling system.[143]

Psychological changes during adolescence are provoked both by physiological changes and being confronted with a different social situation and new expectations from others. An important factor in this period is change to the self-concept, which can take the form of an identity crisis. This process often involves developing individuality and independence from parents while at the same time seeking closeness and conformity with friends and peers. Further developments in this period include improvements to the reasoning ability and the formation of a principled moral view point.[144]

The mind also changes during adulthood but in a less rapid and pronounced manner. Reasoning and problem-solving skills improve during early and middle adulthood. Some people experience the mid-life transition as a midlife crisis involving an inner conflict about personal identity, often associated with anxiety, a sense of lack of accomplishments in life, and an awareness of mortality. Intellectual faculties tend to decline in later adulthood, specifically the ability to learn complex unfamiliar tasks and later also the ability to remember, while people tend to become more inward-looking and cautious.[145]

Mental health and disorder

Mental health is a state of mind characterized by internal equilibrium and

There is a great variety of mental disorders, each associated with a different form of malfunctioning.

There are different approaches to treating mental disorders and the most appropriate treatment usually depends on factors like the type of disorder, its cause, and the person's general condition.

Non-human

Animal

It is commonly acknowledged today that animals have some form of mind, but it is controversial to which animals this applies and how their mind differs from the human mind.

Discontinuity views state that the minds of non-human animals are fundamentally different from human minds and often point to higher mental faculties, like thinking, reasoning, and decision-making based on beliefs and desires.[163] This outlook is reflected in the traditionally influential position of defining humans as "rational animals" as opposed to all other animals.[164] Continuity views, by contrast, emphasize similarities and see the increased human mental capacities as a matter of degree rather than kind. Central considerations for this position are the shared evolutionary origin, organic similarities on the level of brain and nervous system, and observable behavior, ranging from problem-solving skills, animal communication, and reactions to and expressions of pain and pleasure. Of particular importance are the questions of consciousness and sentience, that is, to what extent non-human animals have a subjective experience of the world and are capable of suffering and feeling joy.[165]

Artificial

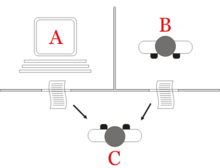

Some of the difficulties of assessing animal minds are also reflected in the topic of artificial minds, that is, the question of whether computer systems implementing artificial intelligence should be considered a form of mind.[166] This idea is consistent with some theories of the nature of mind, such as functionalism and its idea that mental concepts describe functional roles, which are implemented by biological brains but could in principle also be implemented by artificial devices.[167] The Turing test is a traditionally influential procedure to test artificial intelligence: a person exchanges messages with two parties, one of them a human and the other a computer. The computer passes the test if it is not possible to reliably tell which party is the human and which one is the computer. While there are computer programs today that may pass the Turing test, this alone is usually not accepted as conclusive proof of mindedness.[168] For other aspects of mind, it is more controversial whether computers can, in principle, implement them, such as desires, feelings, consciousness, and free will.[169]

This problem is often discussed through the contrast between

Fields and methods of inquiry

Various fields of inquiry study the mind, including psychology, neuroscience, philosophy, and cognitive science. They differ from each other in the aspects of mind they investigate and the methods they employ in the process.[172] The study of the mind poses various problems since it is difficult to directly examine, manipulate, and measure it. Trying to circumvent this problem by investigating the brain comes with new challenges of its own, mainly because of the brain's complexity as a neural network consisting of billions of neurons, each with up to 10,000 links to other neurons.[173]

Psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. It investigates conscious and unconscious mental phenomena, including perception, memory, feeling, thought, decision,

Psychologists use a great variety of methods to study the mind. Experimental approaches set up a controlled situation, either in the laboratory or the field, in which they modify

Neuroscience

Neuroscience is the study of the nervous system. Its primary focus is the central nervous system and the brain in particular, but it also investigates the peripheral nervous system mainly responsible for connecting the central nervous system to the limbs and organs. Neuroscience examines the implementation of mental phenomena on a physiological basis. It covers various levels of analysis; on the small scale, it studies the molecular and cellular basis of the mind, dealing with the constitution of and interaction between individual neurons; on the large scale, it analyzes the architecture of the brain as a whole and its division into regions with different functions.[184]

Philosophy

Philosophy of mind examines the nature of mental phenomena and their relation to the physical world. It seeks to understand the "mark of the mental", that is, the features that all mental states have in common. It further investigates the essence of different types of mental phenomena, such as beliefs, desires, emotions, intentionality, and consciousness while exploring how they are related to one another. Philosophy of mind also examines solutions to the mind–body problem, like dualism, idealism, and physicalism, and assesses arguments for and against them. Further topics are personal identity and free will.[186]

While philosophers of mind also include empirical considerations in their inquiry, they differ from fields like psychology and neuroscience by giving significantly more emphasis to non-empirical forms of inquiry. One such method is

Cognitive science

Cognitive science is the interdisciplinary study of mental processes. It aims to overcome the challenge of understanding something as complex as the mind by integrating research from diverse fields ranging from psychology and neuroscience to philosophy, linguistics, and artificial intelligence. Unlike these disciplines, it is not a unified field but a collaborative effort. One difficulty in synthesizing their insights is that each of these disciplines explores the mind from a different perspective and level of abstraction while using different research methods to arrive at its conclusion.[190]

Cognitive science aims to overcome this difficulty by relying on a unified conceptualization of minds as information processors. This means that mental processes are understood as computations that retrieve, transform, store, and transmit information.[191] For example, perception retrieves sensory information from the environment and transforms it to extract meaningful patterns that can be used in other mental processes, such as planning and decision-making.[192] Cognitive science relies on different levels of description to analyze cognitive processes; the most abstract level focuses on the basic problem the process is supposed to solve and the reasons why the organism needs to solve it; the intermediate level seeks to uncover the algorithm as a formal step-by-step procedure to solve the problem; the most concrete level asks how the algorithm is implemented through physiological changes on the level of the brain.[193] Another methodology to deal with the complexity of the mind is to analyze the mind as a complex system composed of individual subsystems that can be studied independently of one another.[194]

Relation to other fields

The mind is relevant to many fields. In

Anthropology is interested in how different cultures conceptualize the nature of mind and its relation to the world. These conceptualizations affect the way people understand themselves, experience illness, and interpret ritualistic practices as attempts to commune with spirits. Some cultures do not draw a strict boundary between mind and world by allowing that thoughts can pass directly into the world and manifest as beneficial or harmful forces. Others strictly separate the mind as an internal phenomenon without supernatural powers from external reality.[197] Sociology is a related field concerned with the connections between mind, society, and behavior.[198]

The concept of mind plays a central role in various religions.

In the field of

The mind is a frequent subject of

See also

- Outline of human intelligence – topic tree presenting the traits, capacities, models, and research fields of human intelligence, and more.

- Outline of thought – topic tree that identifies many types of thoughts, types of thinking, aspects of thought, related fields, and more.

- Embodied cognition

Notes

- ^ not to be confused with the related term theory of mind

- ^ Mental faculties also play a central role in the Indian tradition, such as the contrast between the sense mind (manas) and intellect (buddhi).[73]

- ^ A different perspective is proposed by the massive modularity hypothesis, which states that the mind is entirely composed of modules with high-level modules establishing the connection between low-level modules.[77]

- ^ The two terms are usually treated as synonyms but some theorists distinguish them by holding that materialism is restricted to matter while physicalism is a wider term that includes additional physical phenomena, like forces.[95]

- ctenophorans.[120]

References

- ^ a b c d "Mind". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ "mind". American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2016. Archived from the original on 2021-06-29. Retrieved 2021-06-29.

- ^ "mind". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. 2014. Archived from the original on 2021-06-29. Retrieved 2021-06-29.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-982815-9.

- ^ Smart, J.J.C., "The Mind/Brain Identity Theory Archived 2013-12-02 at the Wayback Machine", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2011 ed.), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- ^ "What is mind-brain identity theory?". SearchCIO. Tech target. WhatIs. Archived from the original on 2020-04-22. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- S2CID 17852070.

- from the original on 2019-10-24. Retrieved 2018-09-11.

- ^ Karunamuni 2015

- ISBN 978-90-474-4461-9. Archivedfrom the original on 2021-05-10. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- ^ "mind – definition of mind in English | Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on 2017-08-19. Retrieved 2017-08-19.

- ISBN 978-0-415-13273-2. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-04-21. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 2017-10-04. Retrieved 2017-01-02.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Kim, Jaegwon (2006). "1. Introduction". Philosophy of Mind (2nd ed.). Boulder: Westview Press. Archived from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ^ PMID 28736537.

- ^ a b c d Honderich, Ted (2005). "Mind". The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2021-01-29. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ^ Armstrong 2002, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b c d e f g Honderich, Ted (2005). "mind, problems of the philosophy of". The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2021-01-29. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ISBN 978-1-4419-6136-5. Archivedfrom the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2015-04-18.

- ISBN 978-1907321375. Archivedfrom the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ Masters, Frances (2014-08-29). "Harness your Amazingly Creative Mind". www.thefusionmodel.com. Archived from the original on 2015-04-20. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ a b c "Philosophy of mind". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ a b Bourget, David; Mendelovici, Angela (2019). "Phenomenal Intentionality". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ISBN 978-94-017-1611-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ^ from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- PMID 30061466.

- PMID 30061470.

- ^ Huemer, Wolfgang (2019). "Franz Brentano: 3.2 Intentionality". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ^ Heil, John (2004). "Introduction". Philosophy of Mind: A Contemporary Introduction (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge. Archived from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ^ a b Siewert, Charles (2017). "Consciousness and Intentionality". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ a b Jacob, Pierre (2019). "Intentionality". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- from the original on 2021-06-03. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- (PDF) from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ^ a b c Graham, George (2019). "Behaviorism". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Mele, Alfred R. (2003). "Introduction". Motivation and Agency. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2021-06-14. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- from the original on 2021-05-15. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ^ a b Polger, Thomas W. "Functionalism". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-19-926261-8. Archivedfrom the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ^ a b c Levin, Janet (2018). "Functionalism". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Bickle, John (2020). "Multiple Realizability". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 16 March 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Rescorla, Michael (2020). "The Computational Theory of Mind". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 18 December 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Rowlands, Lau & Deutsch 2020, Lead Section, § 1. Introduction.

- ^ Smith, Lead Section.

- ^ Rowlands, Lau & Deutsch 2020, § 1. Introduction, § 3. Content Externalism.

- ^ Smith, § 1. Hilary Putnam and Natural Kind Externalism.

- ^ Rowlands, Lau & Deutsch 2020, § 1. Introduction, § 5. Extended Mind.

- ^ Greif 2017, pp. 4311–4312.

- ^ Rowlands, Lau & Deutsch 2020, § 7. Extended Mind and the 4E Mind.

- ^ Rowlands 2009, pp. 53–56.

- ^

- Sharov 2012, pp. 343–344

- Pashler 2013, pp. xxix–xxx

- Paivio 2014, pp. vi–vii

- Vanderwolf 2013, p. 155

- ^

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 85–86, 123–124

- Martin 1998, Perception

- Gross 2020, pp. 74–76

- Sadri & Flammia 2011, pp. 53–54

- ^

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 208–209, 241

- American Psychological Association 2018e

- ^

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 210, 241

- Tulving 2001, p. 278

- Tsien 2005, p. 861

- ^

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 214–217, 241

- Tsien 2005, p. 861

- ^

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 249, 290

- Ball 2013, pp. 739–740

- ^

- Nunes 2011, p. 2006

- Groarke, § 9. The Syllogism

- Ball 2013, pp. 739–740

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, p. 254

- ^

- Ball 2013, pp. 739–740

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 257–258, 290–291

- ^ Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 265–266, 291

- ^

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, p. 269

- Rescorla 2023, Lead Section

- Aydede 2017

- ^

- Singer 2000, pp. 227–228

- Kind 2017, Lead Section

- American Psychological Association 2018

- Hoff 2020, pp. 617–618

- ^

- Weiner 2000, pp. 314–315

- Helms 2000, lead section

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 298, 336–337

- Müller 1996, p. 14

- ^

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 322–323, 337

- American Psychological Association 2018a

- ^

- ^

- ^

- Kenny 1992, pp. 71–72

- Perler 2015, pp. 3–6, 11

- Hufendiek & Wild 2015, pp. 264–265

- ^

- Kenny 1992, pp. 75

- Perler 2015, pp. 5–6

- ^

- Kenny 1992, pp. 75–76

- Perler 2015, pp. 5–6

- ^

- Kenny 1992, pp. 78–79

- Perler 2015, pp. 5–6

- McLear, § 1i. Sensibility, Understanding, and Reason

- ^

- Deutsch 2013, p. 354

- Schweizer 1993, p. 848

- ^ Robbins 2017, § 1. What is a mental module?

- ^

- Robbins 2017, Lead Section, § 1. What is a mental module?

- Perler 2015, pp. 7

- Hufendiek & Wild 2015, pp. 264–265

- Bermúdez 2014, p. 277

- ^

- Robbins 2017, § 1. What is a mental module?

- Hufendiek & Wild 2015, pp. 265–268

- Bermúdez 2014, pp. 288–290

- ^

- Hufendiek & Wild 2015, pp. 267–268

- Robbins 2017, § 3.1. The case for massive modularity

- Bermúdez 2014, p. 277

- ^

- Robbins 2017, § 1. What is a mental module?

- Hufendiek & Wild 2015, pp. 266–267

- ^

- Robbins 2017, § 1. What is a mental module?

- Bermúdez 2014, p. 289

- ^

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 137–138

- Davies 2001, pp. 190–192

- Gennaro, Lead Section, § 1. Terminological Matters: Various Concepts of Consciousness

- ^

- Davies 2001, pp. 191–192

- Smithies 2019, pp. 83–84

- Gennaro, § 1. Terminological Matters: Various Concepts of Consciousness

- ^

- ^

- Gennaro, Lead Section, § 1. Terminological Matters: Various Concepts of Consciousness

- Kind 2023, § 2.1 Phenomenal Consciousness

- ^

- Mijoia 2005, pp. 1818–1819

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 137–138

- Steinberg Gould 2020, p. 151

- American Psychological Association 2018d

- Carel 2006, p. 176

- ^

- Kim 2005, pp. 607–608

- Swinburne 2013, pp. 72–73

- Lindeman, § 1. General Characterization of the Propositional Attitudes

- ^

- Harman 2013, pp. 1–2

- Broome 2021, § 1. Normativity and Reasons, §2. The Meaning of "Rationality"

- Siegel 2017, p. 157

- Maruyama 2020, pp. 172–173

- ^

- Nolfi 2015, pp. 41–42

- Tappolet 2023, pp. 137–138

- Knauff & Spohn 2021, § 2.2 Basic Concepts of Rationality Assessment, § 4.2 Descriptive Theories

- Vogler 2016, pp. 30–31

- ^

- Bartlett 2018, pp. 1, 4–5

- Schwitzgebel 2024, § 2.1 Occurrent Versus Dispositional Belief

- Wilkes 2012, p. 412

- ^

- Kim 2005, p. 608

- Jaworski 2011, pp. 11–12

- Searle 2004, pp. 3–4

- ^

- Jaworski 2011, pp. 34–36

- Kim 2005, p. 608

- Searle 2004, pp. 13, 41–42

- ^

- Jaworski 2011, pp. 5, 202–203

- Searle 2004, p. 44

- ^

- Jaworski 2011, pp. 5

- Searle 2004, pp. 44, 47–48

- ^ Jaworski 2011, p. 246

- ^ Jaworski 2011, p. 256

- ^

- Marcum 2008, p. 19

- Stoljar 2010, p. 10

- ^

- Jaworski 2011, p. 68

- Stoljar 2024, Lead Section

- Searle 2004, p. 48

- ^

- Jaworski 2011, pp. 71–72

- Searle 2004, pp. 75–76

- ^

- Jaworski 2011, pp. 72–73, 102–104

- Searle 2004, p. 148

- ^

- Ravenscroft 2005, p. 47

- Stoljar 2024, § 2.2.1 Type Physicalism

- ^

- Jaworski 2011, pp. 129–130

- Bigaj & Wüthrich 2015, p. 357

- ^

- Levin 2023, Lead Section

- Searle 2004, p. 62

- ^ Levin 2023, § 1. What is Functionalism?

- ^

- Levin 2023, § 1. What is Functionalism?

- Jaworski 2011, pp. 136–137

- ^

- Weisberg, Lead Section, § 1. Stating the Problem

- Blackmore 2013, pp. 33–35

- Searle 2004, pp. 39–40

- ^

- Opris et al. 2017, pp. 69–70

- Barrett 2009, pp. 326–327

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

- Sanderson & Huffman 2019, pp. 59–61

- Saab 2009, pp. 1–2

- Scanlon & Sanders 2018, pp. 178–180

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

- Winkelman 2011, p. 24

- Meyer et al. 2022, p. 27

- Frankish & Kasmirli 2009, p. 107

- Bunge 2014, p. 18

- ^

- ^

- Macmillan & Lena 2010, pp. 641–643

- Marsh et al. 2007, p. 44

- ^ Macmillan & Lena 2010, p. 655

- ^ Roth 2013, p. 3

- ^ Hatfield 2013, pp. 3–4

- ^

- Hatfield 2013, pp. 4–5

- Roth 2013, pp. 3–4

- ^ Roth 2013, p. 265–266

- ^

- Roth 2013, p. 265–266

- Erulkar & Lentz 2024, § Evolution and development of the nervous system

- Hatfield 2013, pp. 6–7

- ^

- Erulkar & Lentz 2024, § Evolution and development of the nervous system

- Hatfield 2013, p. 13

- ^

- Aboitiz & Montiel 2007, p. 7

- Aboitiz & Montiel 2012, pp. 14–15

- Finlay, Innocenti & Scheich 2013, p. 3

- Jerison 2013, pp. 7–8

- ^

- Hatfield 2013, pp. 6–8

- Reyes & Sherwood 2014, p. 12

- Wragg-Sykes 2016, p. 183

- ^

- Hatfield 2013, p. 9

- Wragg-Sykes 2016, p. 183

- ^

- Roth 2013, pp. 3

- Hatfield 2013, pp. 36–43

- Mandalaywala, Fleener & Maestripieri 2014, pp. 28–29

- ^ OECD (2007). Understanding the Brain: The Birth of a Learning Science. OECD Publishing. p. 165. ISBN 978-92-64-02913-2.

- ^ Chapter 2: The Montessori philosophy. From Lillard, P. P. Lillard (1972). Montessori: A Modern Approach. Schocken Books, New York.

- .

- ^

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 171, 202, 342–343, 384

- Gross 2020, pp. 171–172, 184

- Nairne 2011, pp. 131–132, 240

- ^

- Yeomans & Arnold 2013, p. 31

- Oakley 2004, p. 1

- Nairne 2011, pp. 131–132

- ^

- Coall et al. 2015, pp. 57–58

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 345–346

- Abel 2003, pp. 231–232

- ^ Castiello, U.; Becchio, C.; Zoia, S.; Nelini, C.; Sartori, L.; Blason, L.; D'Ottavio, G.; Bulgheroni, M.; Gallese, V. (2010). "Wired to be social: the ontogeny of human interaction." PloS one, 5(10), p.e13199.

- ^ Kisilevsky, B.C. (2016). "Fetal Auditory Processing: Implications for Language Development? Fetal Development." Research on Brain and Behavior, Environmental In uences, and Emerging Technologies,: 133-152.

- ^ Lee, G.Y.C.; Kisilevsky, B.S. (2014). "Fetuses respond to father’s voice but prefer mother’s voice after birth." Developmental Psychobiology, 56: 1-11.

- ^ Hepper, P.G.; Scott, D.; Shahidullah, S. (1993). "Newborn and fetal response to maternal voice." Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 11: 147-153.

- ^ Lecanuet, J.P.; Granier‐Deferre, C.; Jacquet, A.Y.; Capponi, I.; Ledru, L. (1993). "Prenatal discrimination of a male and a female voice uttering the same sentence." Early development and parenting, 2(4): 217-228.

- ^ Hepper P. (2015). "Behavior during the prenatal period: Adaptive for development and survival." Child Development Perspectives, 9(1): 38-43. DOI: 10.1111/cdep.12104.

- ^ Jardri, R.; Houfflin-Debarge, V.; Delion, P.; Pruvo, J-P.; Thomas, P.; Pins, D. (2012). "Assessing fetal response to maternal speech using a noninvasive functional brain imaging technique." International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience, 2012, 30: 159–161. doi:10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2011.11.002.

- ^

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 342–344, 347–348, 384

- Packer 2017, pp. 7–8

- Smitsman & Corbetta 2011, Action in Infancy – Perspectives, Concepts, and Challenges

- Nairne 2011, pp. 131–132

- ^

- Packer 2017, pp. 7–8

- Freeman 1975, p. 114

- Driscoll & Easterbrooks 2007, p. 256

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, p. 384

- ^

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 349–350

- Gross 2020, pp. 566–572

- ^

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, p. 384

- Harrell 2018, pp. 478–479

- ^

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 384–385

- Gross 2020, pp. 619–620, 625–626

- Berman, Weems & Stickle 2006, pp. 285–292

- Nairne 2011, pp. 124–125, 131–132

- ^

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, p. 385

- Gross 2020, pp. 633–638, 664

- Nairne 2011, pp. 124–125, 131–132

- ^ Murphy, Donovan & Smart 2020, pp. 97–99, 103–104, 112

- ^

- Gross 2020, pp. 731–735

- Nairne 2011, pp. 450–453

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 455–457

- ^

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 466–468

- Gross 2020, pp. 751–752

- Nairne 2011, pp. 459–461

- ^

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 473–474, 476–477

- Gross 2020, p. 755

- Nairne 2011, p. 466

- ^

- Nairne 2011, p. 471

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 485–486

- ^

- Noll 2009, p. 122

- Sharma & Branscum 2020, p. 122

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 480–481

- Nairne 2011, pp. 468–469

- ^

- Gross 2020, p. 766

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 472–473

- ^

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 502–503

- Nairne 2011, pp. 485–486

- Gross 2020, pp. 773–774

- ^

- Nairne 2011, pp. 493–494

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 503–505

- Gross 2020, pp. 781–782

- ^

- Nairne 2011, pp. 493, 495–496

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 508–509

- Gross 2020, pp. 789–790

- ^

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 508–509

- Nairne 2011, pp. 502–503

- Gross 2020, pp. 784–785

- ^

- Nairne 2011, pp. 499–500

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 505–506

- ^

- Bernstein & Nash 2006, pp. 525–527

- Nairne 2011, pp. 487–490

- Gross 2020, pp. 774–779

- ^

- Carruthers 2019, pp. ix, 29–30

- Griffin 1998, pp. 53–55

- ^ Spradlin & Porterfield 2012, pp. 17–18

- ^

- Carruthers 2019, pp. 29–30

- Steiner 2014, p. 93

- Thomas 2020, pp. 999–1000

- ^

- Griffin 2013, p. ix

- Carruthers 2019, p. ix

- Fischer 2021, pp. 28–29

- ^

- Fischer 2021, pp. 30–32

- Lurz, Lead Section

- Carruthers 2019, pp. ix, 29–30

- Penn, Holyoak & Povinelli 2008, pp. 109–110

- ^

- Melis & Monsó 2023, pp. 1–2

- Rysiew 2012

- ^

- Fischer 2021, pp. 32–35

- Lurz, Lead Section

- Griffin 1998, pp. 53–55

- Carruthers 2019, pp. ix–x

- Penn, Holyoak & Povinelli 2008, pp. 109–110

- ^

- McClelland 2021, p. 81

- Franklin 1995, pp. 1–2

- Anderson & Piccinini 2024, pp. 232–233

- Carruthers 2004, pp. 267–268

- ^

- Carruthers 2004, pp. 267–268

- Levin 2023, Lead Section, § 1. What is Functionalism?

- Searle 2004, p. 62

- Jaworski 2011, pp. 136–137

- ^

- Biever 2023, pp. 686–689

- Carruthers 2004, pp. 248–249, 269–270

- ^ Carruthers 2004, pp. 270–273

- ^

- Chen 2023, p. 1141

- Bringsjord & Govindarajulu 2024, § 8. Philosophy of Artificial Intelligence

- Butz 2021, pp. 91–92

- ^

- Bringsjord & Govindarajulu 2024, § 8. Philosophy of Artificial Intelligence

- Fjelland 2020, pp. 1–2

- ^

- Pashler 2013, pp. xxix–xxx

- Friedenberg, Silverman & Spivey 2022, pp. xix, 12–13

- ^

- ^

- Gross 2020, pp. 1–3

- Friedenberg, Silverman & Spivey 2022, pp. 15–16

- ^

- Dawson 2022, pp. 161–162

- Gross 2020, pp. 4–6

- ^

- Higgs, Cooper & Lee 2019, pp. 3–4

- Gross 2020, pp. 4–8

- ^

- Gross 2020, pp. 4–6

- Thornton & Gliga 2020, pp. 35

- Sharma & Sharma 1997, pp. 7–9

- ^ Gross 2020, pp. 4–8

- ^

- Hood 2013, pp. 1314–1315

- Dumont 2008, pp. 17, 48

- Howitt & Cramer 2011, pp. 16–17

- ^

- Dumont 2008, pp. 17, 48

- Howitt & Cramer 2011, pp. 11–12

- ^

- Howitt & Cramer 2011, pp. 232–233

- Dumont 2008, pp. 27–28

- ^

- Howitt & Cramer 2011, pp. 232–233, 294–295

- Dumont 2008, pp. 29–30

- ^

- Howitt & Cramer 2011, pp. 220–221, 383–384

- Dumont 2008, pp. 28

- ^

- Friedenberg, Silverman & Spivey 2022, pp. 17–18

- Hellier 2014, pp. 31–32

- Marcus & Jacobson 2012, p. 3

- ^

- Friedenberg, Silverman & Spivey 2022, pp. 17–18

- Engelmann, Mulckhuyse & Ting 2019, p. 159

- Scharff 2008, pp. 270–271

- Hellier 2014, pp. 31–32

- ^

- Stich & Warfield 2008, pp. ix–x

- Mandik 2014, pp. 1–4, 14

- Kind 2018, Lead Section

- Adams & Beighley 2015, p. 54

- ^

- Stich & Warfield 2008, pp. ix–xi

- Shaffer 2015, pp. 555–556

- Audi 2006, § Philosophical Methods

- ^

- Brown & Fehige 2019, Lead Section

- Goffi & Roux 2011, pp. 165, 168–169

- ^

- Smith 2018, Lead Section, § 1. What is Phenomenology?, §6. Phenomenology and Philosophy of Mind

- Smith 2013, pp. 335–336

- ^

- Friedenberg, Silverman & Spivey 2022, p. 2–3

- Bermúdez 2014, pp. 3, 85

- ^

- Friedenberg, Silverman & Spivey 2022, p. 2–3

- Bermúdez 2014, pp. 3, 85

- ^

- ^

- Friedenberg, Silverman & Spivey 2022, pp. 8–9

- Bermúdez 2014, pp. 122–123

- ^

- Bermúdez 2014, pp. 85, 129–130

- Koenig 2004, p. 274

- ^

- Avramides 2023, Lead Section, § 1.4 Perceptual Knowledge of Other Minds

- Overgaard 2010, pp. 255–258

- ^

- ^

- Luhrmann 2023, Abstract, § Introduction, § Conclusion: The Understanding of Mind in the West is Peculiar

- Toren 2010, pp. 577–580, 582

- Beatty 2019

- ^ Franks 2007, pp. 3055–3056

- ^

- Karunamuni 2015, pp. 1–2

- Coseru 2017, Lead Section; § 2.3 The Five Aggregates

- Laine 1998, Lead Section

- ^

- Laine 1998, § Philosophy of mind in the Upaniṣads

- Rao 2002, pp. 315–316

- ^

- ^

- ^

- Wong 2023, Lead Section

- Hall & Ames 1998

- ^

- Chazan 2022, pp. 15–16

- Bartlett & Burton 2007, pp. 81–85

- Murphy 2003, pp. 5, 19–20

- Wang & Cranton 2013, p. 143

- ^ Emaliana 2017, pp. 59–61

- ^

- Bartlett & Burton 2007, pp. 81–85

- Murphy 2003, pp. 5, 19–20

- ^

- ^

- Stairs 1998, Lead Section

- HarperCollins 2022

Sources

- Abel, Ernest L. (2003). "Fetal Alcohol Syndrome". In Blocker, Jack S.; Fahey, David M.; Tyrrell, Ian R. (eds.). Alcohol and Temperance in Modern History: An International Encyclopedia [2 volumes]. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-1-57607-834-1.

- Aboitiz, F.; Montiel, J. F. (2007). Origin and Evolution of the Vertebrate Telencephalon, with Special Reference to the Mammalian Neocortex. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-49761-5.

- Aboitiz, F.; Montiel, J. F. (2012). "From Tetrapods to Primates: Conserved Developmental Mechanisms in Diverging Ecological Adaptations". In Hofman, Michel A.; Falk, Dean (eds.). Evolution of the Primate Brain: From Neuron to Behavior. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-53860-4.

- Adams, Fred; Beighley, Steve (2015). "The Mark of the Mental". In Garvey, James (ed.). The Bloomsbury Companion to Philosophy of Mind. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4742-4391-9.

- American Psychological Association (2018). "Imagination". APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association.

- American Psychological Association (2018a). "Emotion". APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association.

- American Psychological Association (2018b). "Attention". APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association.

- American Psychological Association (2018c). "Learning". APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association.

- American Psychological Association (2018d). "Unconscious". APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association.

- American Psychological Association (2018e). "Memory". APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association.

- American Psychological Association (2018g). "Neurotransmitter". APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association.

- American Psychological Association (2018f). "Brain". APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association.

- American Psychological Association (2018h). "Theory of Mind". APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association.

- Anderson, Neal G.; Piccinini, Gualtiero (2024). The Physical Signature of Computation: A Robust Mapping Account. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-883364-2.

- Armstrong, D. M. (11 September 2002). A Materialist Theory of the Mind. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-85635-0.

- Athreya, Balu H.; Mouza, Chrystalla (2016). Thinking Skills for the Digital Generation: The Development of Thinking and Learning in the Age of Information. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-12364-6.

- Audi, Robert (2006). "Philosophy". In Borchert, Donald M. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 7: Oakeshott - Presupposition (2. ed.). Thomson Gale, Macmillan Reference. ISBN 978-0-02-865787-5. Archivedfrom the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- Avramides, Anita (2023). "Other Minds". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- Aydede, Murat (2017). "Language of Thought". Oxford Bibliographies. . Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- Ball, Linden J. (2013). "Thinking". In Pashler, Harold (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Mind. Sage. ISBN 978-1-4129-5057-2.

- Barrett, Lisa Feldman (2009). "The Future of Psychology: Connecting Mind to Brain". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 4 (4). .

- Bartlett, Gary (2018). "Occurrent states". Canadian Journal of Philosophy. 48 (1): 1–17. .

- Bartlett, Steve; Burton, Diana (2007). Introduction to Education Studies (2nd ed.). Sage. ISBN 978-1-4129-2193-0.

- Beatty, Andrew (2019). "Psychological Anthropology". Oxford Bibliographies. Oxford University Press. . Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- Benarroch, Eduardo E. (2021). Neuroscience for Clinicians: Basic Processes, Circuits, Disease Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Implications. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-094891-7.

- Berman, Steven L.; Weems, Carl F.; Stickle, Timothy R. (2006). "Existential Anxiety in Adolescents: Prevalence, Structure, Association with Psychological Symptoms and Identity Development". Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 35 (3). .

- Bermúdez, José Luis (2014). Cognitive science: an introduction to the science of the mind (2. ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05162-1.

- Bernstein, Douglas; Nash, Peggy W. (2006). Essentials of Psychology. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-618-71312-7.

- Biever, Celeste (2023). "ChatGPT broke the Turing test — the race is on for new ways to assess AI". Nature. 619 (7971). .

- Bigaj, Tomasz; Wüthrich, Christian (2015). Metaphysics in Contemporary Physics. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-31082-7.

- Blackmore, Susan (2013). Consciousness: An Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-4441-2827-7.

- Bringsjord, Selmer; Govindarajulu, Naveen Sundar (2024). "Artificial Intelligence". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- Broome, John (2021). "Reasons and Rationality". The Handbook of Rationality. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-36185-9.

- Brown, James Robert; Fehige, Yiftach (2019). "Thought Experiments". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 21 November 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- Bunge, Mario (2014). The Mind–Body Problem: A Psychobiological Approach. Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4831-5012-3.

- Butz, Martin V. (2021). "Towards Strong AI". KI - Künstliche Intelligenz. 35 (1). .

- Carel, Havi (2006). Life and Death in Freud and Heidegger. Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-1659-0.

- Carruthers, Peter (2004). The Nature of the Mind: An Introduction (1 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 0-415-29994-2.

- Carruthers, Peter (2019). Human and animal minds: the consciousness questions laid to rest (1 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-884370-2.

- Chazan, Barry (2022). "What is "Education"?". Principles and Pedagogies in Jewish Education. Springer International Publishing. pp. 13–21. S2CID 239896844.

- Chen, Zhaoman (2023). "Exploration of Youth Social Work Model Driven by Artificial Intelligence". In Hung, Jason C.; Yen, Neil Y.; Chang, Jia-Wei (eds.). Frontier Computing: Theory, Technologies and Applications (FC 2022). Springer Nature. ISBN 978-981-99-1428-9.

- Clark, Kelly James; Lints, Richard; Smith, James K. A. (2004). "Mind/Soul/Spirit". 101 Key Terms in Philosophy and Their Importance for Theology. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22524-7.

- Coall, David A.; Callan, Anna C.; Dickins, Thomas E.; Chisholm, James S. (2015). "Evolution and Prenatal Development: An Evolutionary Perspective". Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science, Socioemotional Processes. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-95387-7.

- Coseru, Christian (2017). "Mind in Indian Buddhist Philosophy". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- Dash, Paul; Villemarette-Pitman, Nicole (2005). Alzheimer's Disease. Demos Medical Publishing. ISBN 978-1-934559-49-9.

- Davies, Martin (2001). "Consciousness". In Wilson, Robert A.; Keil, Frank C. (eds.). The MIT Encyclopedia of the Cognitive Sciences (MITECS). MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-73144-7.

- Dawson, Michael R. W. (2022). What Is Cognitive Psychology?. Athabasca University Press. ISBN 978-1-77199-342-5.

- Deutsch, Eliot (2013). "The Self in Advaita Vedanta". In Perrett, Roy W. (ed.). Metaphysics: Indian Philosophy. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-70266-3.

- Dixon, Thomas; Shapiro, Adam (2022). "5. Mind, Brain, and Morality". Science and Religion: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-256677-5.

- Driscoll, Joan Riley; Easterbrooks, M. Ann (2007). "Development, Emotional". In Cochran, Moncrieff; New, Rebecca S. (eds.). Early Childhood Education: An International Encyclopedia [4 volumes]. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-0-313-01448-2.

- Dumont, K. (2008). "2. Research Methods and Statistics". In Nicholas, Lionel (ed.). Introduction to Psychology. University of Capetown Press. ISBN 978-1-919895-02-4.

- Dunbar, Robin I. M. (2007). "Brain and Cognition in Evolutionary Perspective;". In Platek, Steven; Keenan, Julian; Shackelford, Todd Kennedy (eds.). Evolutionary Cognitive Neuroscience. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-16241-8.

- Duncan, Stewart; LoLordo, Antonia (2013). "Introduction". Debates in Modern Philosophy: Essential Readings and Contemporary Responses. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-13660-4.

- Emaliana, Ive (2017). "Teacher-Centered or Student-Centered Learning Approach To Promote Learning?". Jurnal Sosial Humaniora. 10 (2): 59. S2CID 148796695.

- Engelmann, Jan B.; Mulckhuyse, Manon; Ting, Chih-Chung (2019). "Brain Measurement and Manipulation Methods;". In Schram, Arthur; Ule, Aljaž (eds.). Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Experimental Economics. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78811-056-3.

- Erulkar, Solomon D.; Lentz, Thomas L. (2024). "Nervous system". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- Finlay, Barbara L.; Innocenti, Giorgio M.; Scheich, Henning (2013). "Evolutionary and Developmental Syntheses: Introduction". The Neocortex: Ontogeny and Phylogeny. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4899-0652-6.

- Fischer, Bob (2021). Animal Ethics: A Contemporary Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-48440-5.

- Fjelland, Ragnar (2020). "Why General Artificial Intelligence Will Not be Realized". Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. 7 (1). ISSN 2662-9992.

- Frankish, Keith; Kasmirli, Maria (2009). "8. Mind and Consciousness". In Shand, John (ed.). Central Issues of Philosophy. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-6270-8.

- Franklin, Stan (1995). Artificial minds. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-06178-3.

- Franks, David D. (2007). "Mind". In Ritzer, George (ed.). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-2433-1.

- Freeman, Derek (1975). "Kinship, Attachment Behaviour and the Primary Bond". In Goody, Jack (ed.). The Character of Kinship. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29002-9.

- Friedenberg, Jay; Silverman, Gordon; Spivey, Michael (2022). Cognitive Science: An Introduction to the Study of Mind (4 ed.). Sage Publications. ISBN 9781544380155.

- Gennaro, Rocco J. "Consciousness". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- Goffi, Jean-Yves; from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- Greif, Hajo (November 2017). "What is the extension of the extended mind?". Synthese. 194 (11): 4311–4336. PMID 29200511.

- Griffin, Donald R. (1998). "Mind, Animal". States of Brain and Mind. Springer Science. ISBN 978-1-4899-6773-2.

- Griffin, Donald R. (2013). Animal Minds: Beyond Cognition to Consciousness. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-22712-2.

- Groarke, Louis F. "Aristotle: Logic". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- Gross, Richard (2020). Psychology: The Science of Mind and Behaviour (8 ed.). Hodder Education. ISBN 978-1-5104-6846-7.

- Hall, David L.; Ames, Roger T. (1998). "Xin (heart-and-mind)". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge. . Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- Harman, Gilbert (2013). "Rationality". The International Encyclopedia of Ethics (1 ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-1-4051-8641-4.

- HarperCollins (2022). "Parapsychology". The American Heritage Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- Harrell, Stevan (2018). Human Families. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-8133-3622-0.

- Hatfield, Gary (2013). "Introduction: The Evolution of Mind, Brain, and Culture". In Hatfield, Gary; Pittman, Holly (eds.). Evolution of Mind, Brain, and Culture. University of Pennsylvania Museum of archaeology and anthropology. ISBN 978-1-934536-49-0.

- Hellier, Jennifer L. (2014). "Introduction: Neuroscience Overview". The Brain, the Nervous System, and Their Diseases: [3 volumes]. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-1-61069-338-7.

- Helms, Marilyn M., ed. (2000). "Motivation and Motivation Theory". Encyclopedia of Management (4. ed.). Gale Group. ISBN 978-0-7876-3065-2. Archivedfrom the original on 2021-04-29. Retrieved 2021-05-13.

- Higgs, Suzanne; Cooper, Alison; Lee, Jonathan (2019). Biological Psychology. Sage Publications. ISBN 978-1-5264-8278-5.

- Hoff, Eva V. (2020). "Imagination". In Runco, Mark A.; Pritzker, Steven R. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Creativity. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-815615-5.

- Hood, Ralph W. (2013). "Methodology in Psychology". Encyclopedia of Sciences and Religions. Springer Netherlands. ISBN 978-1-4020-8265-8.

- Howitt, Dennis; Cramer, Duncan (2011). Introduction to Research Methods in Psychology (3 ed.). Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-273-73499-4.

- Hufendiek, Rebekka; Wild, Markus (2015). "6. Faculties and Modularity". The Faculties: A History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-993527-7.

- Jaworski, William (2011). Philosophy of Mind: A Comprehensive Introduction (1 ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4443-3367-1.

- Jerison, H. J. (2013). "Fossil Brains and the Evolution of the Neocortex". In Finlay, Barbara L.; Innocenti, Giorgio M.; Scheich, Henning (eds.). The Neocortex: Ontogeny and Phylogeny. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4899-0652-6.

- Karunamuni, Nandini D. (2015). "The Five-Aggregate Model of the Mind". Sage Open. 5 (2). .

- Kenny, Anthony (1992). "5. Abilities, Faculties, Powers, and Dispositions". The Metaphysics of Mind. pp. 66–85. ISBN 9780191670527.

- Kihlstrom, John F.; Tobias, Betsy A. (1991). "Anosognosia, Consciousness, and the Self". In Prigatano, George P.; Schacter, Daniel L. (eds.). Awareness of Deficit After Brain Injury: Clinical and Theoretical Issues. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-505941-0.

- Kim, Jaegwon (2005). "Mind, Problems of the Philosophy of". The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926479-7. Archivedfrom the original on 11 April 2024. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- Kind, Amy (2017). "Imagination". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. ISBN 978-0-415-25069-6.

- Kind, Amy (2018). "The Mind–Body Problem in 20th-Century Philosophy". Philosophy of Mind in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries: The History of the Philosophy of Mind, Volume 6. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-01938-8.

- Kind, Amy (2023). "1. The Mind-Body Problem: Dualism Rebooted". In Kind, Amy; Stoljar, Daniel (eds.). What is Consciousness?: A Debate. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-86666-7.

- Knauff, Markus; Spohn, Wolfgang (2021). "Psychological and Philosophical Frameworks of Rationality—A Systematic Introduction". The Handbook of Rationality. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-36185-9.

- Koenig, Oliver (2004). "Modularity: Neuroscience". In Houdé, Olivier; Kayser, Daniel; Koenig, Olivier; Proust, Joëlle; Rastier, François (eds.). Dictionary of Cognitive Science: Neuroscience, Psychology, Artificial Intelligence, Linguistics, and Philosophy. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-45635-1.

- Laine, Joy (1998). "Mind, Indian philosophy of". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge. . Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- Levin, Janet (2023). "Functionalism". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- Lindeman, David. "Propositional Attitudes". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- Luhrmann, Tanya Marie (2023). "Mind". The Open Encyclopedia of Anthropology. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- Lurz, Robert. "Minds, Animal". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- Macmillan, Malcolm; Lena, Matthew L. (2010). "Rehabilitating Phineas Gage". Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 20 (5). .

- Mandalaywala, Tara; Fleener, Christine; Maestripieri, Dario (2014). "Intelligence in Nonhuman Primates". In Goldstein, Sam; Princiotta, Dana; Naglieri, Jack A. (eds.). Handbook of Intelligence: Evolutionary Theory, Historical Perspective, and Current Concepts. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4939-1562-0.

- Mandik, Pete (2014). This is Philosophy of Mind: An Introduction. Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 9780470674475.

- Marcum, James A. (2008). An Introductory Philosophy of Medicine: Humanizing Modern Medicine. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4020-6797-6.

- Marcus, Elliott M.; Jacobson, Stanley (2012). Integrated Neuroscience: A Clinical Problem Solving Approach. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4615-1077-2.

- Marsh, Ian; Melvill, Gaynor; Morgan, Keith; Norris, Gareth; Walkington, Zoe (2007). Theories of Crime. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-19842-9.

- Martin, M. G. F. (1998). "Perception". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-07310-3.

- Maruyama, Yoshihiro (2020). "Rationality, Cognitive Bias, and Artificial Intelligence: A Structural Perspective on Quantum Cognitive Science". In Harris, Don; Li, Wen-Chin (eds.). Engineering Psychology and Cognitive Ergonomics: Cognition and Design Part 2. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-49183-3.

- McClelland, Tom (2021). What is Philosophy of Mind?. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-5095-3878-2.

- McLear, Colin. "Kant: Philosophy of Mind". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- McPeek, Robert M. (2009). "Attention: Physiological". In Goldstein, E. Bruce (ed.). Encyclopedia of Perception. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-4522-6615-2.

- Melis, Giacomo; Monsó, Susana (2023). "Are Humans the Only Rational Animals?". The Philosophical Quarterly. .

- Meyer, Jerrold S.; Meyer, Jerry; Farrar, Andrew M.; Biezonski, Dominik; Yates, Jennifer R. (2022). Psychopharmacology: Drugs, the Brain, and Behavior. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-60535-987-8.

- Mijoia, Alain de (2005). "The Unconscious". International Dictionary of Psychoanalysis. Macmillan Reference USA. ISBN 0-02-865927-9.

- Murphy, Dominic; Donovan, Caitrin; Smart, Gemma Lucy (2020). "Mental Health and Well-Being in Philosophy". In Sholl, Jonathan; Rattan, Suresh I. S. (eds.). Explaining Health Across the Sciences. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-52663-4.

- Murphy, Patricia (2003). "1. Defining Pedagogy". In Gipps, Caroline V. (ed.). Equity in the Classroom: Towards Effective Pedagogy for Girls and Boys. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-71682-0. Archivedfrom the original on 25 January 2024. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- Müller, Jörg P. (1996). The Design of Intelligent Agents: A Layered Approach. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-62003-7.

- Nairne, James S. (2011). Psychology (5 ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-8400-3310-9.

- Nolfi, Kate (2015). "Which Mental States Are Rationally Evaluable, And Why?". Philosophical Issues. 25 (1): 41–63. .

- Noll, Richard (2009). The Encyclopedia of Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8160-7508-9.

- Nunes, Terezinha (5 October 2011). "Logical Reasoning and Learning". In Seel, Norbert M. (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781441914279.

- Oakley, Lisa (2004). Cognitive Development. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-54743-2.

- Opris, Ioan; Casanova, Manuel F.; Lebedev, Mikhail A.; Popescu, Aurel I. (2017). "Prefrontal Cortical Microcircuits Support the Emergence of Mind". In Opris, Ioan (ed.). The Physics of the Mind and Brain Disorders: Integrated Neural Circuits Supporting the Emergence of Mind. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. ISBN 978-3-319-29672-2.

- Overgaard, Søren (2010). "The Problem of Other Minds". Handbook of Phenomenology and Cognitive Science. Springer Netherlands. ISBN 978-90-481-2646-0.

- Packer, Martin J. (2017). Child Development: Understanding A Cultural Perspective. Sage. ISBN 978-1-5264-1311-6.

- Paivio, Allan (2014). Mind and Its Evolution: A Dual Coding Theoretical Approach. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-317-71690-7.

- Pashler, Harold (2013). "Introduction". Encyclopedia of the Mind. Sage. ISBN 978-1-4129-5057-2.

- Penn, Derek C.; Holyoak, Keith J.; Povinelli, Daniel J. (2008). "Darwin's Mistake: Explaining the Discontinuity between Human and Nonhuman Minds". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 31 (2). .

- Perler, Dominik (2015). "Introduction". The Faculties: A History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-993527-7.

- Popescu, Aurel I.; Opris, Ioan (2017). "Introduction: From Neurons to the Mind". In Opris, Ioan (ed.). The Physics of the Mind and Brain Disorders: Integrated Neural Circuits Supporting the Emergence of Mind. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. ISBN 978-3-319-29672-2.

- Rao, A. Venkoba (2002). "'Mind' in Indian philosophy". Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 44 (4). PMID 21206593.

- Rassool, G. Hussein (2021). Islamic Psychology: Human Behaviour and Experience from an Islamic Perspective. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-36292-3.

- Ravenscroft, Ian (2005). Philosophy of Mind: A Beginner's Guide. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925254-1.

- Reisyan, Garo D. (2015). Neuro-Organizational Culture: A new approach to understanding human behavior and interaction in the workplace. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-22147-2.

- Rescorla, Michael (2023). "The Language of Thought Hypothesis". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- Reyes, Laura D.; Sherwood, Chet C. (2014). "Neuroscience and Human Brain Evolution". In Bruner, Emiliano (ed.). Human Paleoneurology. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-08500-5.

- Robbins, Philip (2017). "Modularity of Mind". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- Roth, Gerhard (2013). The Long Evolution of Brains and Minds. Springer. ISBN 978-94-007-6258-9.

- Rothman, Abdallah (2021). Developing a Model of Islamic Psychology and Psychotherapy: Islamic Theology and Contemporary Understandings of Psychology. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-41621-3.

- Rowlands, Mark; Lau, Joe; Deutsch, Max (2020). "Externalism About the Mind". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- Rowlands, Mark (March 2009). "Enactivism and the Extended Mind". Topoi. 28 (1): 53–62. .

- Rysiew, Patrick (2012). "Rationality". Oxford Bibliographies. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- Saab, Carl Y. (2009). The Hindbrain. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-1965-6.

- Sadri, Houman A.; Flammia, Madelyn (2011). Intercultural Communication: A New Approach to International Relations and Global Challenges. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4411-0309-3.

- Sanderson, Catherine A.; Huffman, Karen R. (2019). Real World Psychology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-57775-1.

- Scanlon, Valerie C.; Sanders, Tina (2018). Essentials of Anatomy and Physiology. F. A. Davis. ISBN 978-0-8036-9006-6.

- Scharff, Lauren Fruh VanSickle (2008). "Sensation and Perception Research Methods". In Davis, Stephen F. (ed.). Handbook of Research Methods in Experimental Psychology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-75672-0.

- Schoenberg, Mike R.; Marsh, Patrick J.; Lerner, Alan J. (2011). "Neuroanatomy Primer: Structure and Function of the Human Nervous System". In Schoenberg, Mike R.; Scott, James G. (eds.). The Little Black Book of Neuropsychology: A Syndrome-Based Approach. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-76978-3.

- Schweizer, Paul (1993). "Mind/Consciousness Dualism in Sankhya-Yoga Philosophy". Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 53 (4). JSTOR 2108256.

- Schwitzgebel, Eric (2024). "Belief". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 20 April 2024.

- Searle, John R. (2004). Mind: A Brief Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515733-8.

- Shaffer, Michael J. (2015). "The Problem of Necessary and Sufficient Conditions and Conceptual Analysis". Metaphilosophy. 46 (4–5). .

- Sharma, Rajendra Kumar; Sharma, Rachana (1997). Social Psychology. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. ISBN 978-81-7156-707-2.

- Sharma, Manoj; Branscum, Paul (2020). Foundations of Mental Health Promotion. Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 978-1-284-19975-8.

- Sharov, Alexei A. (2012). "Minimal Mind". In Swan, Liz (ed.). Origins of Mind. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-94-007-5419-5.

- Siegel, Harvey (2017). Education's Epistemology: Rationality, Diversity, and Critical Thinking. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-068267-5.

- Singer, Jerome L. (2000). "Imagination". In Kazdin, Alan E. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Psychology (Volume 4). American Psychological Association [u.a.] ISBN 978-1-55798-187-5.

- Smith, Basil. "Internalism and Externalism in the Philosophy of Mind and Language". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- Smith, David Woodruff (2013). "Phenomenological Methoda in Philosophy of Mind". In Haug, Matthew (ed.). Philosophical Methodology: The Armchair or the Laboratory?. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-10710-9.

- Smith, David Woodruff (2018). "Phenomenology". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- Smithies, Declan (2019). The Epistemic Role of Consciousness. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-094853-5.

- Smitsman, Ad W.; Corbetta, Daniela (2011). "Action in Infancy – Perspectives, Concepts, and Challenges". In Bremner, J. Gavin; Wachs, Theodore D. (eds.). The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Infant Development, Volume 1: Basic Research. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-5183-5.

- Spradlin, W. W.; Porterfield, P. B. (2012). The Search for Certainty. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4612-5212-2.

- Spruit, Leen (2008). "Renaissance Views of Active Perception". In Knuuttila, Simo; Kärkkäinen, Pekka (eds.). Theories of Perception in Medieval and Early Modern Philosophy. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4020-6125-7.

- Stairs, Allen (1998). "Parapsychology". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge. . Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- Steinberg Gould, Carol (2020). "6. Psychoanalysis, Imagination, and Imaginative Resistance: A Genesis of the Post-Freudian World". In Moser, Keith; Sukla, Ananta (eds.). Imagination and Art: Explorations in Contemporary Theory. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-43635-0.

- Steiner, Gary (2014). "Cognition and Community". In Petrus, Klaus; Wild, Markus (eds.). Animal Minds & Animal Ethics: Connecting Two Separate Fields. transcript Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8394-2462-9.

- Stich, Stephen P.; Warfield, Ted A. (2008). "Introduction". The Blackwell Guide to Philosophy of Mind. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-99875-5.

- Stoljar, Daniel (2010). Physicalism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-14922-2.

- Stoljar, Daniel (2024). "Physicalism". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- Swinburne, Richard (2013). Mind, Brain, and Free Will. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-105744-1.

- Sysling, Fenneke (2022). "Human Sciences and Technologies of the Self Since the Nineteenth Century". In McCallum, David (ed.). The Palgrave Handbook of the History of Human Sciences. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-981-16-7255-2.

- Tappolet, Christine (2023). Philosophy of Emotion: A Contemporary Introduction. Routlege. ISBN 978-1-138-68743-1.

- Thomas, Evan (2020). "Descartes on the Animal Within, and the Animals Without". Canadian Journal of Philosophy. 50 (8). ISSN 0045-5091.

- Thornton, Stephanie; Gliga, Teodora (2020). Understanding Developmental Psychology. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-137-00669-1.

- Toren, Christina (2010). "Psychological Anthropology". In Barnard, Alan; Spencer, Jonathan (eds.). The Routledge encyclopedia of social and cultural anthropology. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-40978-0.

- Tsien, Joe Z. (2005). "Learning and Memory". In Albers, R. Wayne; Price, Donald L. (eds.). Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-047207-2.

- Tulving, Endel (2001). "Episodic vs. Semantic Memory". In Wilson, Robert A.; Keil, Frank C. (eds.). The MIT Encyclopedia of the Cognitive Sciences (MITECS). MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-73144-7.

- Turkington, Carol; Mitchell, Deborah R. (2010). "Hippocampus". The Encyclopedia of Alzheimer's Disease. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-2858-0.

- Uttal, William R. (2011). Mind and Brain: A Critical Appraisal of Cognitive Neuroscience. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01596-7.

- Vanderwolf, Case H. (2013). An Odyssey Through the Brain, Behavior and the Mind. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4757-3779-0.

- Vogler, Candace A. (2016). John Stuart Mill's Deliberative Landscape (Routledge Revivals): An Essay in Moral Psychology. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-20617-0.