Sleipnir

In Norse mythology, Sleipnir /ˈsleɪpnɪər/ (Old Norse: "slippy"[1] or "the slipper"[2]) is an eight-legged horse ridden by Odin. Sleipnir is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. In both sources, Sleipnir is Odin's steed, is the child of Loki and Svaðilfari, is described as the best of all horses, and is sometimes ridden to the location of Hel. The Prose Edda contains extended information regarding the circumstances of Sleipnir's birth, and details that he is grey in color.

Sleipnir is also mentioned in a riddle found in the 13th-century

Scholarly theories have been proposed regarding Sleipnir's potential connection to

Attestations

Poetic Edda

In the Poetic Edda, Sleipnir appears or is mentioned in the poems

Prose Edda

In the Prose Edda book

In chapter 42, Sleipnir's origins are described.

The gods declare that Loki would deserve a horrible death if he could not find a scheme that would cause the builder to forfeit his payment, and threatened to attack him. Loki, afraid, swore oaths that he would devise a scheme to cause the builder to forfeit the payment, whatever it would cost himself. That night, the builder drove out to fetch stone with his stallion Svaðilfari, and out from a wood ran a mare. The mare neighed at Svaðilfari, and "realizing what kind of horse it was," Svaðilfari became frantic, neighed, tore apart his tackle, and ran towards the mare. The mare ran to the wood, Svaðilfari followed, and the builder chased after. The two horses ran around all night, causing the building work to be held up for the night, and the previous momentum of building work that the builder had been able to maintain was not continued.[10]

When the Æsir realize that the builder is a

In chapter 49, High describes the death of the god

In chapter 16 of the book Skáldskaparmál, a kenning given for Loki is "relative of Sleipnir."[12] In chapter 17, a story is provided in which Odin rides Sleipnir into the land of Jötunheimr and arrives at the residence of the jötunn Hrungnir. Hrungnir asks "what sort of person this was" wearing a golden helmet, "riding sky and sea," and says that the stranger "has a marvellously good horse." Odin wagers his head that no horse as good could be found in all of Jötunheimr. Hrungnir admitted that it was a fine horse, yet states that he owns a much longer-paced horse; Gullfaxi. Incensed, Hrungnir leaps atop Gullfaxi, intending to attack Odin for Odin's boasting. Odin gallops hard ahead of Hrungnir, and, in his, fury, Hrungnir finds himself having rushed into the gates of Asgard.[13] In chapter 58, Sleipnir is mentioned among a list of horses in Þorgrímsþula: "Hrafn and Sleipnir, splendid horses [...]".[14] In addition, Sleipnir occurs twice in kennings for "ship" (once appearing in chapter 25 in a work by the skald Refr, and "sea-Sleipnir" appearing in chapter 49 in Húsdrápa, a work by the 10th century skald Úlfr Uggason).[15]

Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks

In Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks, the poem Heiðreks gátur contains a riddle that mentions Sleipnir and Odin:

- 36. Gestumblindi said:

- "Who are the twain

- that on ten feet run?

- three eyes they have,

- but only one tail.

- Alright guess now

- this riddle, Heithrek!"

Völsunga saga

In chapter 13 of Völsunga saga, the hero Sigurðr is on his way to a wood and he meets a long-bearded old man he had never seen before. Sigurd tells the old man that he is going to choose a horse, and asks the old man to come with him to help him decide. The old man says that they should drive the horses down to the river Busiltjörn. The two drive the horses down into the deeps of Busiltjörn, and all of the horses swim back to land but a large, young, and handsome grey horse that no one had ever mounted. The grey-bearded old man says that the horse is from "Sleipnir's kin" and that "he must be raised carefully, because he will become better than any other horse." The old man vanishes. Sigurd names the horse Grani, and the narrative adds that the old man was none other than (the god) Odin.[17]

Gesta Danorum

Sleipnir is generally considered as appearing in a sequence of events described in book I of Gesta Danorum.[18]

In book I, the young

In book II, Biarco mentions Odin and Sleipnir: "If I may look on the awful husband of Frigg, howsoever he be covered in his white shield, and guide his tall steed, he shall in no way go safe out of Leire; it is lawful to lay low in war the war-waging god."[20]

Archaeological record

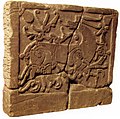

Two of the 8th century picture stones from the island of Gotland, Sweden depict eight-legged horses, which are thought by most scholars to depict Sleipnir: the Tjängvide image stone and the Ardre VIII image stone. Both stones feature a rider sitting atop an eight-legged horse, which some scholars view as Odin. Above the rider on the Tjängvide image stone is a horizontal figure holding a spear, which may be a valkyrie, and a female figure greets the rider with a cup. The scene has been interpreted as a rider arriving at the world of the dead.[21] The mid-7th century Eggja stone bearing the Odinic name haras (Old Norse 'army god') may be interpreted as depicting Sleipnir.[22] The English Runic Inscription 2 (11th century) is also believed by some scholars to depict Sleipnir.[23]

-

The Ardre VIII image stone

Theories

John Lindow theorizes that Sleipnir's "connection to the world of the dead grants a special poignancy to one of the kennings in which Sleipnir turns up as a horse word," referring to the skald Úlfr Uggason's usage of "sea-Sleipnir" in his Húsdrápa, which describes the funeral of Baldr. Lindow continues that "his use of Sleipnir in the kenning may show that Sleipnir's role in the failed recovery of Baldr was known at that time and place in Iceland; it certainly indicates that Sleipnir was an active participant in the mythology of the last decades of paganism." Lindow adds that the eight legs of Sleipnir "have been interpreted as an indication of great speed or as being connected in some unclear way with cult activity."[21]

Hilda Ellis Davidson says that "the eight-legged horse of Odin is the typical steed of the shaman" and that in the shaman's journeys to the heavens or the underworld, a shaman "is usually represented as riding on some bird or animal." Davidson says that while the creature may vary, the horse is fairly common "in the lands where horses are in general use, and Sleipnir's ability to bear the god through the air is typical of the shaman's steed" and cites an example from a study of shamanism by Mircea Eliade of an eight-legged foal from a story of a Buryat shaman. Davidson says that while attempts have been made to connect Sleipnir with hobby horses and steeds with more than four feet that appear in carnivals and processions, but that "a more fruitful resemblance seems to be on the bier on which a dead man is carried in the funeral procession by four bearers; borne along thus, he may be described as riding on a steed with eight legs." As an example, Davidson cites a funeral dirge from the Gondi people in India as recorded by Verrier Elwin, stating that "it contains references to Bagri Maro, the horse with eight legs, and it is clear from the song that it is the dead man's bier." Davidson says that the song is sung when a distinguished Muria dies, and provides a verse:[24]

- What horse is this?

- It is the horse of Bagri Maro.

- What should we say of its legs?

- This horse has eight legs.

- What should we say of its heads?

- This horse has four heads. . . .

- Catch the bridle and mount the horse.[24]

Davidson adds that the representation of Odin's steed as eight-legged could arise naturally out of such an image, and that "this is in accordance with the picture of Sleipnir as a horse that could bear its rider to the land of the dead."[24]

Ulla Loumand cites Sleipnir and the flying horse

The

Modern influence

According to Icelandic folklore, the

See also

- List of horses in mythology and folklore

- Helhest, the three-legged "Hel horse" of later Scandinavian folklore

- Horses in Germanic paganism

- The "táltos steed", a six-legged horse in Hungarian folklore

- Pegasus, the winged horse of Greek mythology

- Sinterklaas's white stallion, on which he rides along the roofs in winter

- The horse in Nordic mythology

Notes

- ^ Orchard (1997:151).

- ^ Kermode (1904:6).

- ^ Larrington (1999:58).

- ^ Larrington (1999:169).

- ^ Larrington (1999:243).

- ^ Larrington (1999:258).

- ^ Faulkes (1995:18).

- ^ Faulkes (1995:34).

- ^ Faulkes (1995:35).

- ^ a b Faulkes (1995:36).

- ^ Faulkes (1995:49–50).

- ^ Faulkes (1995:76).

- ^ Faulkes (1995:77).

- ^ Faulkes (1995:136).

- ^ Faulkes (1995:92 and 121).

- ^ Hollander (1936:99).

- ^ Byock (1990:56).

- ^ Lindow (2001:276–277).

- ^ Grammaticus & Elton (2006:104–105).

- ^ Grammaticus & Elton (2006:147).

- ^ a b Lindow (2001:277).

- ^ Simek (2007:140).

- ISBN 0-521-82992-5p. 73

- ^ a b c Davidson (1990:142–143).

- ^ Loumand (2006:133).

- ^ Mallory. Adams (1997:163).

- ^ a b Simek (2007:294).

- ^ Municipality of Oslo (26 June 2001). "Yggdrasilfrisen" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 25 January 2009. Retrieved 2 December 2008.

- ^ Kipling, Rudyard (1909). Abaft the Funnel. New York: B. W. Dodge & Company. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ^ Noszlopy, Waterhouse (2005:181).

References

- Byock, Jesse (Trans.) (1990). The Saga of the Volsungs: The Norse Epic of Sigurd the Dragon Slayer. ISBN 0-520-23285-2

- ISBN 0-14-013627-4

- Faulkes, Anthony (Trans.) (1995). Edda. ISBN 0-460-87616-3

- Grammaticus, Saxo; Elton, Oliver (1905). The Danish History. New York: Norroena Society. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2014. (reprinted in 2005 by BiblioBazaar)

- Hollander, Lee Milton (1936). Old Norse Poems: The Most Important Nonskaldic Verse Not Included in the Poetic Edda Archived 25 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Columbia University Press

- Kermode, Philip Moore Callow (1904). Traces of Norse Mythology in the Isle of Man. Harvard University Press.

- Larrington, Carolyne (Trans.) (1999). The Poetic Edda. ISBN 0-19-283946-2

- ISBN 0-19-515382-0

- Loumand, Ulla (2006). "The Horse and its Role in Icelandic Burial Practices, Mythology, and Society". In Andrén, Anders; Jennbert, Kristina; et al. (eds.). Old Norse Religion in Long Term Perspectives: Origins, Changes and Interactions, an International Conference in Lund, Sweden, June 3–7, 2004. Lund: Nordic Academic Press. ISBN 91-89116-81-X.

- ISBN 1-884964-98-2

- Noszlopy, George Thomas. Waterhouse, Fiona (2005). Public Sculpture of Staffordshire and the Black Country. ISBN 0-85323-989-4

- Orchard, Andy (1997). Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. ISBN 0-304-34520-2

- ISBN 0-85991-513-1