Alpha-synuclein

Ensembl | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UniProt | |||||||||

| RefSeq (mRNA) |

| ||||||||

| RefSeq (protein) |

| ||||||||

| Location (UCSC) | Chr 4: 89.7 – 89.84 Mb | Chr 6: 60.71 – 60.81 Mb | |||||||

| PubMed search | [3] | [4] | |||||||

| View/Edit Human | View/Edit Mouse |

Alpha-synuclein (aSyn) is a

It is abundant in the brain, while smaller amounts are found in the heart, muscle and other tissues. In the brain, alpha-synuclein is found mainly in the

In

Familial Parkinson's disease is associated with mutations in the -synuclein (SNCA) gene. In the process of seeded nucleation, alpha-synuclein acquires a cross-sheet structure similar to other amyloids.[12]

The human alpha-synuclein protein is made of 140 amino acids.[13][14][15] An alpha-synuclein fragment, known as the non-amyloid beta (non-Abeta) component (NAC) of Alzheimer's disease amyloid, originally found in an amyloid-enriched fraction, was shown to be a fragment of its precursor protein, NACP.[13] It was later determined that NACP is the human homologue of synuclein in electric rays, genus Torpedo. Therefore, NACP is now referred to as human alpha-synuclein.[16]

Tissue expression

Alpha-synuclein is a

It has been established that alpha-synuclein is extensively localized in the nucleus of mammalian brain neurons, suggesting a role of alpha-synuclein in the nucleus.

It has also been shown that alpha-synuclein is localized in neuronal

, hippocampus, striatum and thalamus, where the cytosolic alpha-synuclein is also rich. However, the cerebral cortex and cerebellum are two exceptions, which contain rich cytosolic alpha-synuclein but very low levels of mitochondrial alpha-synuclein. It has been shown that alpha-synuclein is localized in the inner membrane of mitochondria, and that the inhibitory effect of alpha-synuclein on complex I activity of the mitochondrial respiratory chain is dose-dependent. Thus, it is suggested that alpha-synuclein in mitochondria is differentially expressed in different brain regions and the background levels of mitochondrial alpha-synuclein may be a potential factor affecting mitochondrial function and predisposing some neurons to degeneration.[24]At least three isoforms of synuclein are produced through alternative splicing.[25] The majority form of the protein, and the one most investigated, is the full-length protein of 140 amino acids. Other isoforms are alpha-synuclein-126, which lacks residues 41-54 due to loss of exon 3; and alpha-synuclein-112,[26] which lacks residues 103-130 due to loss of exon 5.[25]

In the enteric nervous system (ENS)

First characterisations of aSyn aggregates in the ENS of PD patients has been performed on autopsied specimens in the late 1980s.[27] It is yet unknown if the microbiome changes associated with PD are consequential to the illness process or main pathophysiology, or both.[28]

Individuals diagnosed with various synucleinopathies often display constipation and other GI dysfunctions years prior to the onset of movement dysfunction. [29]

Alpha synuclein potentially connects the gut-brain axis in Parkinson's disease patients. Common inherited Parkinson disease is associated with mutations in the alpha-synuclein (SNCA) gene. In the process of seeded nucleation, alpha-synuclein acquires a cross-sheet structure similar to other amyloids. [27]

The Enterobacteriaceae, which are quite common in the human gut, can create curli, which are functional amyloid proteins. The unfolded amyloid CsgA, which is secreted by bacteria and later aggregates extracellularly to create biofilms, mediates adherence to epithelial cells, and aids in bacteriophage defense, forms the curli fibers. Oral injection of curli-producing bacteria can also boost formation and aggregation of the amyloid protein Syn in old rats and nematodes. Host inflammation responses in the intestinal tract and periphery are modulated by curli exposure. Studies in biochemistry show that endogenous, bacterial chaperones of curli are capable of briefly interacting with Syn and controlling its aggregation.[29]

The clinical and pathological findings support the hypothesis that aSyn disease in PD occurs via a gut-brain pathway. For early diagnosis and early management in the phase of creation and propagation of aSyn, it is therefore of utmost importance to identify pathogenic aSyn in the digestive system, for example, by gastrointestinal tract (GIT) biopsies.[27]

According to a growing body of research, intestinal dysbiosis may be a major factor in the development of Parkinson's disease by encouraging intestinal permeability, gastrointestinal inflammation, and the aggregation and spread of asyn.[27]

Not just the CNS but other peripheral tissues, such as the GIT, have physiological aSyn expression as well as its phosphorylated variants.[30] As suggested by Borghammer and Van Den Berge (2019), one approach is to recognise the possibility of PD subtypes with various aSyn propagation methods, including either a peripheral nervous system (PNS)-first or a CNS-first route.[31]

While the GI tract has been linked to other neurological disorders such autism spectrum disorder, depression, anxiety, and Alzheimer's disease, protein aggregation and/or inflammation in the gut represent a new topic of investigation in synucleinopathies.[29]

Structure

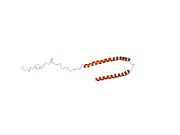

Alpha-synuclein in solution is considered to be an

Alpha-synuclein is specifically

Apparently, alpha-synuclein is essential for normal development of the cognitive functions. Knock-out mice with the targeted inactivation of the expression of alpha-synuclein show impaired spatial learning and working memory.[42]

Interaction with lipid membranes

Experimental evidence has been collected on the interaction of alpha-synuclein with membrane and its involvement with membrane composition and turnover. Yeast genome screening has found that several genes that deal with lipid metabolism and mitochondrial fusion play a role in alpha-synuclein toxicity.[43][44] Conversely, alpha-synuclein expression levels can affect the viscosity and the relative amount of fatty acids in the lipid bilayer.[45]

Alpha-synuclein is known to directly bind to lipid membranes, associating with the negatively charged surfaces of

Function

Although the function of alpha-synuclein is not well understood, studies suggest that it plays a role in restricting the mobility of synaptic vesicles, consequently attenuating

Alpha-synuclein modulates

Proneurogenic function of alpha-synuclein

In some

Sequence

Alpha-synuclein

- Residues 1-60: An amphipathic N-terminal region dominated by four 11-residue repeats including the consensus sequence KTKEGV. This sequence has a structural alpha helix propensity similar to apolipoproteins-binding domains.[74] It is a highly conserved terminal that interacts with acidic lipid membranes, and all the discovered point mutations of the SNCA gene are located within this terminal.[75]

- Residues 61-95: A central hydrophobic region which includes the non-amyloid-β component (NAC) region, involved in protein aggregation.[13] This domain is unique to alpha-synuclein among the synuclein family.[76]

- Residues 96-140: a highly acidic and proline-rich region which has no distinct structural propensity. This domain plays an important role in the function, solubility and interaction of alpha-synuclein with other proteins.[77][40]

Autoproteolytic activity

The use of high-resolution

Clinical significance

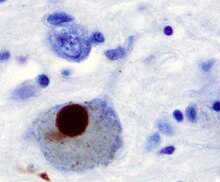

Alpha synuclein, having no single, well-defined tertiary structure, is an

The aggregation mechanism of alpha-synuclein is uncertain. There is evidence of a structured intermediate rich in

In rare cases of familial forms of

It has been reported that some mutations influence the initiation and amplification steps of the aggregation process.[116][117] Genomic duplication and triplication of the gene appear to be a rare cause of Parkinson's disease in other lineages, although more common than point mutations.[118][119] Hence certain mutations of alpha-synuclein may cause it to form amyloid-like fibrils that contribute to Parkinson's disease. Over-expression of human wild-type or A53T-mutant alpha-synuclein in primates drives deposition of alpha-synuclein in the ventral midbrain, degeneration of the dopaminergic system and impaired motor performance.[120]

Certain sections of the alpha-synuclein protein may play a role in the

A prion form of the protein alpha-synuclein may be a causal agent for the disease multiple system atrophy.[124][125][126]

Self-replicating "prion-like" amyloid assemblies of alpha-synuclein have been described that are invisible to the amyloid dye Thioflavin T and that can acutely spread in neurons in vitro and in vivo.[128]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2015) |

Protein-protein interactions

Alpha-synuclein has been shown to

- Dopamine transporter,[130][131]

- Phospholipase D1,[134]

- SNCAIP,[135][136][137][138]

- Tau protein.[139][140][141]

- Beta amyloid[142]

See also

- Synuclein

- Contursi Terme - the village in Italy where a mutation in the α-synuclein gene led to a family history of Parkinson's disease

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000145335 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000025889 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b c d e "Genetics Home Reference: SNCA". U.S. National Library of Medicine. 12 Nov 2013. Retrieved 14 Nov 2013.

- S2CID 18772904.

- S2CID 18173864.

- S2CID 27116894.

- ^ PMID 31110017.

- PMID 31110014.

- S2CID 4419837.

- )

- ^ PMID 8248242.

- PMID 12214035. Archived from the originalon 2016-05-14. Retrieved 2009-02-19.

- ^ Xia Y, Saitoh T, Uéda K, Tanaka S, Chen X, Hashimoto M, Hsu L, Conrad C, Sundsmo M, Yoshimoto M, Thal L, Katzman R, Masliah E (2002). "Characterization of the human alpha-synuclein gene: Genomic structure, transcription start site, promoter region and polymorphisms: Erratum p489 Fig 3". J. Alzheimers Dis. 4 (4): 337. Archived from the original on 2016-05-14. Retrieved 2009-02-19.

- S2CID 36840279.

- ^ S2CID 17941420.

- S2CID 58006790.

- S2CID 24698373.

- S2CID 37294944.

- PMID 10722726.

- S2CID 10438997.

- S2CID 1737088.

- ^ S2CID 45120745.

- ^ S2CID 1367846.

- PMID 7802671.

- ^ PMID 33015066.

- S2CID 245351514.

- ^ PMID 32043464.

- PMID 28057070.

- PMID 31498132.

- S2CID 36085937.

- PMID 8901511.

- PMID 24475132.

- S2CID 11421888.

- S2CID 84374030.

- PMID 15345814.

- S2CID 18772904.

- S2CID 18173864.

- ^ PMID 20798282.

- PMID 16794039.

- S2CID 205884600.

- ^ Tauro M (4 February 2019). "Alpha-Synuclein Toxicity is Caused by Mitochondrial Dysfunction". Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository.

- S2CID 43221047.

- ^ S2CID 85334400.

- PMID 19066219.

- S2CID 41555488.

- PMID 16669622.

- PMID 20693280.

- PMID 22767608.

- PMID 23609437.

- ^ PMID 28579098.

- PMID 16800638.

- ^ PMID 29702073.

- PMID 28474754.

- S2CID 1604719.

- S2CID 24760126.

- PMID 20580911.

- PMID 25580849.

- PMID 17108165.

- PMID 20152114.

- PMID 20554859.

- PMID 22836248.

- PMID 25009269.

- PMID 25264250.

- PMID 28108534.

- PMID 23100443.

- PMID 25246573.

- PMID 23638301.

- ^ PMID 31358782.

- PMID 29150919.

- PMID 34485283.

- PMID 29217686.

- S2CID 20654921.

- PMID 12787676.

- PMID 26446103.

- PMID 31912891.

- PMID 22162214.

- PMID 28498720.

- ^ PMID 32632432.

- PMID 34235468.

- PMID 24901537.

- PMID 22424229.

- PMID 21841800.

- PMID 22006323.

- PMID 23319586.

- PMID 23184946.

- PMID 22407793.

- PMID 22988846.

- S2CID 34960247.

- PMID 23991082.

- S2CID 2649589.

- ^ PMID 22315227.

- .

- PMID 22694283.

- PMID 18493022.

- PMID 23765500.

- S2CID 4461465.

- S2CID 4419837.

- S2CID 46196799.

- S2CID 125080534.

- S2CID 11144367.

- S2CID 22950302.

- S2CID 42542929.

- S2CID 41870508.

- PMID 18198943.

- PMID 20563819.

- ^ Morshedi D, Aliakbari F (Spring 2012). "The Inhibitory Effects of Cuminaldehyde on Amyloid Fibrillation and Cytotoxicity of Alpha-synuclein". Modares Journal of Medical Sciences: Pathobiology. 15 (1): 45–60.

- S2CID 84387269.

- PMID 9197268.

- S2CID 40777043.

- S2CID 55263.

- S2CID 13508258.

- S2CID 43305127.

- PMID 34229155.

- PMID 10075647.

- PMID 27573854.

- S2CID 85938327.

- S2CID 54419671.

- PMID 17303591.

- S2CID 20223000.

- S2CID 27393027.

- PMID 33094280.

- PMID 26324905.

- ^ Weiler N (31 August 2015). "New Type of Prion May Cause, Transmit Neurodegeneration".

- ^ Rettner R (31 August 2015). "Another Fatal Brain Disease May Come from the Spread of 'Prion' Proteins". Wired Science.

- PMID 19193223.

- PMID 33008896.

- S2CID 40155547.

- S2CID 54381509.

- S2CID 3406798.

- S2CID 83941655.

- PMID 18195004.

- S2CID 85695661.

- S2CID 11517781.

- PMID 1742726.

- S2CID 83885937.

- S2CID 2611127.

- S2CID 9545889.

- S2CID 23877061.

- S2CID 9086733.

- S2CID 17593306.

Further reading

- Blakeslee S (2002-05-27). "In Folding Proteins, Clues to Many Diseases". New York Times.

- Siderowf A, Concha-Marambio L, Lafontant DE, Farris CM, Ma Y, Urenia PA, Nguyen H, Alcalay RN, Chahine LM, Foroud T, Galasko D, Kieburtz K, Merchant K, Mollenhauer B, Poston KL, Seibyl J, Simuni T, Tanner CM, Weintraub D, Videnovic A, Choi SH, Kurth R, Caspell-Garcia C, Coffey CS, Frasier M, Oliveira LM, Hutten SJ, Sherer T, Marek K, Soto C (May 2023). "Assessment of heterogeneity among participants in the Parkinson's Progression Markers Initiative cohort using α-synuclein seed amplification: a cross-sectional study". Lancet Neurol. 22 (5): 407–417. S2CID 258083747.

External links

Media related to Alpha-synuclein at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Alpha-synuclein at Wikimedia Commons- alpha-Synuclein at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Human SNCA genome location and SNCA gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.