Bernardo de Gálvez

Spanish Governor of Louisiana | |

|---|---|

| In office 1777–1783 | |

| Monarch | Charles III |

| Preceded by | Luis de Unzaga |

| Succeeded by | Esteban Rodríguez Miró |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid 23 July 1746 Captain General Marshal |

| Battles/wars |

|

Bernardo Vicente de Gálvez y Madrid, 1st Count of Gálvez (23 July 1746 – 30 November 1786) was a Spanish military leader and government official who served as colonial governor of Spanish Louisiana and Cuba, and later as Viceroy of New Spain.

A

Gálvez's actions aided the American war effort and made him a hero to both Spain and the newly independent United States. The U.S. Congress endeavored to hang his portrait in the Capitol, finally doing so in 2014.[2] He was granted many titles and honors by the Spanish government, which in 1783 appointed him viceroy of one of its most valuable territories, New Spain, succeeding his father Matías de Gálvez y Gallardo. He served until his death from typhus.

While somewhat forgotten in the United States, Gálvez remains in high esteem among many Americans, particularly in the southern and western states that once formed part of Spain's North American territory.

Origins and military career

Bernardo de Gálvez was born in

In 1772, Gálvez returned to Spain with his uncle,

Spanish governor of Louisiana

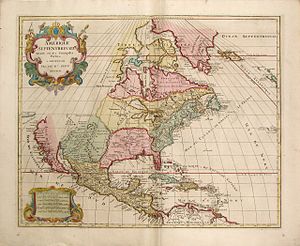

On 1 January 1777, Bernardo de Gálvez became the new governor of the formerly French province of Louisiana,[13][18] the vast territory that would later become the object of the Louisiana Purchase. The colony had been ceded by France to Spain in 1762, ostensibly as compensation for the loss of Florida to Britain, after Spain was urged to enter the Seven Years' War on the French side.

In November 1777, Gálvez married Marie Félicité de Saint-Maxent d'Estrehan, the Creole daughter of the French-born

As governor, Gálvez enacted an anti-British policy, taking measures against British smuggling and promoting trade with France.[24][25] He damaged British interests in the region and kept it open for supplies to reach George Washington's army during the American Revolutionary War.[26][27][28] He founded Galvez Town in 1779,[27] promoted the colonization of Nueva Iberia, and established free trade with Cuba and Yucatán.[29] Galvez Street in New Orleans is named for him. In 1779, Gálvez was promoted to brigadier.[30]

American Revolutionary War

In December 1776, King Charles III of Spain decided that covert assistance to the United States would be strategically useful, but Spain did not enter into a formal alliance with the U.S.[31] In 1777, José de Gálvez, newly appointed as minister of the Council of the Indies, sent his nephew, Bernardo de Gálvez, to New Orleans as governor of Luisiana with instructions to secure the friendship of the United States.[32] On 20 February 1777, the Spanish king's ministers in Madrid secretly instructed Gálvez to sell the Americans desperately needed supplies.[25] The British had blockaded the colonial ports of the Thirteen Colonies, and consequently the route from New Orleans up the Mississippi River was an effective alternative. Gálvez worked with Oliver Pollock, an American patriot, to ship gunpowder, muskets, uniforms, medicine, and other supplies to the American colonial rebels.[33]

Although Spain had not yet joined the American cause, when an American raiding expedition led by James Willing showed up in New Orleans with booty and several captured British ships taken as prizes, Gálvez refused to turn the Americans over to the British.[33][34][35] In 1779, Spanish forces commanded by Gálvez seized the province of West Florida, later known as the Florida Parishes, from the British.[36] Spain's motive was the chance both to recover territories lost to the British, particularly Florida, and to remove the ongoing British threat.[37][38][39]

On 21 June 1779, Spain formally declared war on Great Britain.

Gálvez carried out a masterful military campaign and defeated the British colonial forces at

Gálvez's most important military victory over the British forces occurred 8 May 1781, when he attacked and took by land and by sea

In 1782, forces under Gálvez's overall command

Gálvez received many honors from Spain for his military victories against the British, including promotion to lieutenant general and field marshal,[58] governor and captain general of Louisiana and Florida (now separated from Cuba), the command of the Spanish expeditionary army in America, and the titles of Viscount of Gálvez-Town and Count of Gálvez.[59]

The American Revolutionary War ended while Gálvez was preparing a new campaign to take Jamaica. From the American perspective, Gálvez's campaign denied the British the opportunity of encircling the American rebels from the south and kept open a vital conduit for supplies. He also assisted the American revolutionaries with supplies and soldiers, much of it through Oliver Pollock,[60] from whom he received military intelligence concerning the British in West Florida.[61][62] For France and Spain, Gálvez's military success in the American war effort led to the inclusion of provisions in the Peace of Paris (1783) that officially returned Florida, now divided into two provinces, East and West Florida, to Spain. The treaty recognized the political independence of the former British colonies to the north, and its signing ended their war with the British.[63][64]

Viceroy of New Spain

In 1783, Bernardo de Gálvez was ennobled to the rank of count, promoted to lieutenant-general of the army, and appointed governor and captain-general of Cuba.

During his administration two great calamities occurred: the freeze of September 1785, which led to famine in 1786,[69] and a typhus epidemic that killed 300,000 people the same year.[70] During the famine, Gálvez donated 12,000 pesos of his inheritance and 100,000 pesos he raised from other sources to buy maize and beans for the populace.[71] He also implemented policies to increase future agricultural production.

In 1785, Gálvez initiated construction of Chapultepec Castle.[72][73][74] He also ordered the construction of the towers of the cathedral and paving of the streets, as well as the installation of streetlights in Mexico City.[75] He continued work on the highway to Acapulco,[71][76][77] and took measures to reduce the abuse of Indian labor on the project. He dedicated 16% of the income from the lottery and other games of chance to charity.

Gálvez helped advance science in the colony by sponsoring the Royal Botanical Expedition to New Spain, led by Martín Sessé y Lacasta. This expedition of botanists and naturalists resulted in a comprehensive catalog, a collaborative work published in Spain as the Flora Mexicana, which catalogued the diverse species of plants, birds, and fish found in New Spain.[78]

On one occasion, when the viceroy was riding on horseback to meet with the

After the typhus epidemic of 1786 had abated in early autumn, Bernardo de Gálvez apparently became one of its last victims,[80] and was confined to his bed. On 8 November 1786, he turned over all his governmental duties except the captain generalship to the Audiencia.[81] On 30 November 1786, Galvez died at the age of 40 in Tacubaya (now part of Mexico City). Gálvez was buried next to his father at San Fernando Church in Mexico City.[82][83]

Bernardo de Gálvez left some writings, including Ordenanzas para el Teatro de Comedias de México[84] and Instrución para el Buen Gobierno de las Provincias Internas de la Nueva España (Instructions for Governing the Interior Provinces of New Spain, 1786),[85] the latter of which remained in effect until the colonial period ended.[86] In his "Instructions", Gálvez advocated a policy of selling the Indians rifles and trade goods to make them dependent on the Spanish government,[87] and sanctioned war against the Apache if these inducements failed to pacify them.[88][89]

Legacy

Galveston, Texas, Galveston Bay, Galveston County, Galvez, Louisiana, and St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana were, among other places, named after him. The Louisiana parishes of East Feliciana and West Feliciana (originally a single parish) were said to have been named for his wife Marie Felicite de Saint-Maxent d'Estrehan.[90]

In Baton Rouge, Louisiana (present-day state capital), Galvez Plaza is laid out next to City Hall and used frequently as a site for municipal events.[94] Also, the 13-story Galvez Building is part of the state government's administrative office-building complex in the Capitol Park section of downtown Baton Rouge.

In 1911, the Hotel Galvez was built in Galveston Avenue P, where the hotel is located, is known as Bernardo de Galvez Avenue. The hotel was added to the National Register of Historic Places on 4 April 1979.

On December 16, 2014, the United States Congress conferred honorary citizenship on Gálvez, citing him as a "hero of the Revolutionary War who risked his life for the freedom of the United States people and provided supplies, intelligence, and strong military support to the war effort."[95] In 2019, the Spanish Government placed a 32-inch-tall (80 cm) statue of Galvez in front of the Spanish Embassy in Washington, D.C.[96]

Heraldry

- Heraldry of Bernardo de Gálvez

-

Coat of Arms as Count of Gálvez (1783–1786)

See also

- Bernardo de Gálvez, the 1976 equestrian statue in Washington, D.C.

- Gálveztown (brig sloop) – captured British ship renamed and participated in the capture of Mobile (1780); replica built in Spain more than 200 years later.

- Spain and the American Revolutionary War

- Matías de Gálvez y Gallardo, Bernardo's father

- José de Gálvez, Bernardo's uncle

Notes

- ^ "Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid's Very Good Year". Roll Call. 2014-12-29. Retrieved 2022-01-31.

- ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2022-01-31.

- ^ a b Bridget Bowman (29 December 2014). "Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid's Very Good Year". Roll Call. The Economist Group. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ José Antonio Calderón Quijano (1968). Los Virreyes de nueva España en el reinado de Carlos III.: Martín de Mayorga (1779–1783), por J. J. Real Díaz y A. M. Heredia Herrera. Matías de Gálvez (1783–1784), por M. Rodríguez del Valle y A. Conejo Díez de la Cortina. Bernardo de Gálvez (1785–1786), por Ma. del Carmen Galbis Díez. Alonso Núnez de Haro, 1787, por A. Rubio Gil. Escuela Gráfica Salesiana. p. 327.

- ISBN 978-0-300-05917-5.

- ^ Luis Navarro García (1964). Don José de Gálvez y la Comandancia General de las Provincias Internas del norte de Nueva España. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. p. 143.

- ISBN 84-00-06091-1.

- ISBN 9788450021561.

- ^ a b John Walton Caughey (1934). Bernardo de Gálvez in Louisiana, 1776–1783. University of California Press. p. 62.

- ISBN 978-1-4728-0300-9.

- JSTOR 40169957.

- ISBN 978-0-300-15117-6.

- ^ ISSN 1132-8312. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-8061-2317-2.

- ISBN 978-84-9060-614-8.

- ISBN 9788450021561.

- ISBN 978-1-4556-1227-7.

- ^ Michael Klein. "Louisiana: European Explorations and the Louisiana Purchase – Louisiana under Spanish Rule" (PDF). loc.gov/collections. United States Library of Congress. p. 40. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ Madame Calderón de la Barca (Frances Erskine Inglis) (1959). La vida en Mexico durante una residencia de dos afios en ese pais. Porrúa. p. 44.

- ISBN 978-1-4556-1234-5.

- ISBN 9780939566006.

- ISBN 978-1-101-87524-7.

- ^ Dictionary of Louisiana Biography (2008). "ST. MAXENT, Marie Félicité (Felicítas)". www.lahistory.org. Louisiana Historical Association. Archived from the original on July 16, 2016. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-887366-51-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8117-0077-1.

- ^ "Caughey 1934, p. 250"

- ^ a b Louisiana Review. Conseil pour le développement du français en Louisiane. 1975. p. 68.

- ISBN 978-1-4696-1834-0.

- ISBN 978-607-445-280-8..

Estableció el libre tráfico de Nueva Orleáns con Cuba y Yucatán y fomentó la colonización de Nueva Iberia." (English): "He established New Orleans' free trade with Cuba and Yucatán and promoted the colonization of New Iberia

- ISBN 978-0-8263-2795-6.

- ISBN 978-0-19-025776-7.

- ISBN 978-0-89875-978-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-101-87525-4.

- ISBN 978-0-393-24883-8.

- ISBN 978-0-945274-72-8.

- ISBN 978-0-8071-2270-9.

- ^ Helen Hornbeck Tanner (1963). Zéspedes in East Florida, 1784–1790. University of Miami Press. p. 11.

- ISBN 978-0-87404-207-8.

- ISBN 978-0-8386-3389-2.

- ISBN 978-0-87436-837-6.

- ^ "Chávez 2002" p. 135

- ISBN 978-0-8108-7503-6.

- ISBN 0-8032-8192-7.

- ^ George C. Osborn (April 1949). "Major-General John Campbell in British West Florida". Florida Historical Quarterly. XXVII (4): 335. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

Again, in November 1780, Germain informed Campbell that it was "the King's Wish" that Governor Dalling, Vice-Admiral Parker and he collaborate in an attack on New Orleans. General Campbell was to do all in his power to render the attack successful.

- ISBN 9780939566006.

- ISBN 0-618-15464-7.

- ^ Great Britain. Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts (1906). Report on American Manuscripts in the Royal Institution of Great Britain ... H. M. Stationery Office. p. 162.

- ^ "Osborn1949" p. 326

- ISBN 978-0-8071-2793-3.

- ISBN 978-0-7864-3213-4.

- ISBN 978-1-135-07772-3.

- ISBN 978-0-8071-1527-5.

- ^ N. Orwin Rush (1966). Spain's Final Triumph Over Great Britain in the Gulf of Mexico: The Battle of Pensacola March 9 to May 8, 1781. Florida State University. pp. 82–83.

- ^ "Ferreiro 2016", p.253–254

- ISBN 978-0-8061-4988-2.

- ^ William Spence Robertson (1909). Francisco de Miranda and the Revolutionizing of Spanish America. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 240–242.

- ^ "Chávez 2002" pp. 208–209

- ISBN 978-0-19-521930-2.

- ISBN 978-0-674-06544-4.

- ^ "Chávez 2002" p. 108

- ISBN 978-0-8071-5711-4.

- ISBN 978-0-393-25387-0.

- ISBN 978-0-7881-4722-7.

- ISBN 978-0-8129-8120-9.

- ISBN 978-1-137-01080-3.

- OCLC 1029828120.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ISBN 978-0-300-15621-8.

- ISBN 978-0-226-36300-4.

- ISBN 978-1-317-62113-3.

- .

The worst famine of the colonial era in Mexico occurred in 1786, and is referred to as El Ano de Hambre the year of hunger (Florescano and Swan, 1995; Therrell, 2005). Two to three years of drought and an early fall frost in 1785 again appear to have led to crop failure and famine in 1786 (Therrell, 2005; Therrell et al., 2006). An estimated 300,000 people died during El Ano de Hambre due to both famine and an outbreak of epidemic typhus in 1785–1787 (Cooper, 1965; Burns et al., 2014). The MXDA indicates that drought conditions were most serious during the two-year period from 1785 to 1786 when drought extended over most of Mexico, most severely over central and northeastern Mexico

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7614-2938-8.

- ISBN 978-0-8420-2467-9.

- ^ "Chávez 2002", p. 12

- ISBN 978-607-452-266-2.

- ISBN 978-0-313-30049-3.

- ^ a b The Historical Magazine, and Notes and Queries Concerning the Antiquities, History, and Biography of America. Vol. VIII. C. Benjamin Richardson. 1864. p. 141.

- ISBN 978-968-16-4390-4.

- ISBN 978-0-8166-7092-5.

- ISBN 9788450021561.

- ^ Publications of the University of California at Los Angeles in Social Sciences. University of California Press. 1934. p. 256.

- ^ Artes de México. Frente Nacional de Artes Plásticas. 1960. p. 90.

- ^ "Chávez 2002", p. 219

- ^ Revista complutense de historia de América. Facultad de Geografía e Historia, Universidad Complutense de Madrid. 2006. p. 192.

- ^ Francisco Pimentel (1904). Obras completas. Vol. IV. Tipografía económica. p. 351.

- ^ New Spain; Bernardo de Gálvez (1951). Instructions for Governing the Interior Provinces of New Spain, 1786. Quivira Society.

- ISBN 978-0-300-10501-8.

- ISBN 978-0-300-19689-4.

- ISBN 978-0-8061-3084-2.

- ISBN 978-0-8191-7983-8.

- ISBN 978-0-674-06544-4.

- ISBN 978-1-4556-1519-3.

- ISBN 978-1-62584-509-2.

- ^ Robert B. Kane (August 2, 2016). "Bernardo de Gálvez". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Auburn University. Archived from the original on June 25, 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-8071-1715-6.

- ^ "H.J.Res.105 - Conferring honorary citizenship of the United States on Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid, Viscount of Galveston and Count of Gálvez". Congress.gov. 2014-12-16. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ John Kelly (July 17, 2019), “The Spaniard Who Helped Win the Revolutionary War Has a New Statue in D.C.,” The Washington Post.

Further reading

- Caughey, John Walton (1998). Bernardo de Gálvez in Louisiana 1776–1783, Gretna: Pelican Publishing Company.

- Chávez, Thomas E. (2002). Spain and the Independence of the United States: An Intrinsic Gift, Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Gálvez, Bernardo de (1967) [1786]. Instructions for Governing the Interior Provinces of New Spain, 1786. New York: Arno Press.

- Mitchell, Barbara (Autumn 2010). "America's Spanish Savior: Bernardo de Gálvez marches to rescue the colonies". MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History: 98–104.

- Quintero Saravia, Gonzalo M. Bernardo de Gálvez: Spanish Hero of the American Revolution (2018). 616 pp Scholarly biography; online review

- Ritter, Luke. "The American Revolution on the Periphery of Empires: Don Bernardo de Gálvez & the Spanish-American Alliance, 1763–1783." Journal of Early American History (2017) 7#2:177-201.

- Thonhoff, Robert H. (2000). The Texas Connection With The American Revolution. ISBN 1-57168-418-2.

- Woodward, Ralph Lee Jr. Tribute to Don Bernardo de Gálvez. Baton Rouge : Historic New Orleans Collection, 1979.

- (in Spanish) "Gálvez, Bernardo de," Enciclopedia de México, v. 6. Mexico City: 1987.

- (in Spanish) García Puron, Manuel (1984). México y sus gobernantes, v. 1. Mexico City: Joaquín Porrua.

- (in Spanish) Orozco L., Fernando (1988). Fechas Históricas de México. Mexico City: Panorama Editorial, ISBN 968-38-0046-7.

- (in Spanish) Orozco Linares, Fernando (1985). Gobernantes de México. Mexico City: Panorama Editorial, ISBN 968-38-0260-5.

External links

- De Gálvez entry at United States National Park Service

- Bernardo de Gálvez at Texas A & M University

- Spain's Role in the American Revolution at AmericanRevolution.org