Spanish Texas

| History of Texas | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| History of Spain |

|---|

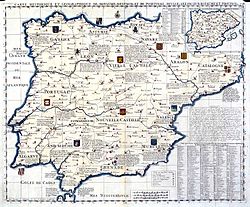

18th century map of Iberia |

| Timeline |

Spanish Texas was one of the

The Spanish returned to southeastern Texas in 1716, establishing several

During the

The Spanish never achieved control of most of Texas which was on the far frontier of Spanish colonial ambitions. Despite the meager nature of Spanish colonization, Hispanic influence in Texas is extensive. Spanish architectural concepts still flourish. Many cities and rivers in Texas were named by the Spanish and many counties in southern and western Texas have majority Hispanic populations. The inadvertent introduction of European diseases by the Spanish caused Native American populations to plummet, leaving a population vacuum later filled by Anglo American settlers. Grazing of European livestock caused mesquite to spread inland replacing native grassland while Spanish farmers tilled and irrigated the land and changed the landscape. Although Texas eventually adopted much of the Anglo-American legal system, many Spanish legal practices survived, including the concepts of a homestead exemption and of community property.

Location

Spanish Texas (Tejas) was a colonial province within the northeastern mainland region of the

Initial colonization attempts

Although

In 1685, the Spanish learned that France had established a colony in the area between

De León sent a report of his findings to Mexico City, where it "created instant optimism and quickened religious fervor".[10] The Spanish government was convinced that the destruction of the French fort was "proof of God's 'divine aid and favor'".[10] In his report de León recommended that presidios be established along the Rio Grande, the Frio River, and the Guadalupe River and that missions be established among the Hasinai Indians,[11] whom the Spanish called the Tejas,[12] in East Texas. In Castilian Spanish, this was often written as the phonetic equivalent Texas, which became the name of the future province.[13]

Missions

The

On January 23, 1691, Spain appointed the first governor of Texas, General

The group also left a

Conflict with France

During the early eighteenth century, France again provided the impetus for Spain's interest in Texas. In 1699, French forts were established at

In 1711, Franciscan missionary

On April 12, 1716, an expedition led by Domingo Ramón left San Juan Bautista for Texas, intending to establish four missions and a presidio which would be guarded by twenty-five soldiers.[28][29] The party of 75 people included 3 children, 7 women, 18 soldiers, and 10 missionaries.[27] These were the first recorded female settlers in Spanish Texas.[29] After marrying a Spanish woman, St. Denis also joined the Spanish expedition.[27]

The party reached the land of the

During this period, the area was named the New Philippines by the missionaries in the twin hopes of gaining royal patronage, and that the Spanish efforts would be as successful as in the Philippines a century and a half earlier. The alternate name became official and remained in use for several decades, but had virtually disappeared from use (in favor of 'Texas') by the end of the century. The name however persisted in documents, especially in land grants [32]

At the same time, the French were building a fort in Natchitoches to establish a more westward presence. The Spanish countered by founding two more missions just west of Natchitoches, San Miguel de los Adaes and Dolores de los Ais.[12] The missions were located in a disputed area; France claimed the Sabine River to be the western boundary of Louisiana, while Spain claimed the Red River was the eastern boundary of Texas, leaving an overlap of 45 miles (72 km).[2]

The new missions were over 400 miles (640 km) from the nearest Spanish settlement,

The following year, the

The Marquis of San Miguel de Aguayo volunteered to reconquer Texas and raised an army of 500 soldiers.[39] Aguayo was named the governor of Coahuila and Texas and the responsibilities of his office delayed his trip to Texas by a year, until late 1720.[40] Just before he departed, the fighting in Europe halted, and King Felipe V of Spain ordered them not to invade Louisiana, but instead find a way to retake Eastern Texas without using force.[39] The expedition brought with them over 2,800 horses, 6,400 sheep and many goats; this constituted the first large "cattle drive" in Texas. This greatly increased the number of domesticated animals in Texas and marked the beginning of Spanish ranching in Texas.[41]

In July 1721, while approaching the

Settlement difficulties

Shortly after Aguayo returned to Mexico, the new viceroy of New Spain,

Rivera recommended closing Presidio de los Tejas and reducing the number of soldiers at the other presidios. His suggestions were approved in 1729,[49] and 125 troops were removed from Texas, leaving only 144 soldiers divided among Los Adaes, La Bahía, and San Antonio. The three East Texas missions which had depended on Presidio de los Tejas were relocated along the San Antonio River in May 1731, increasing the number of missions in the San Antonio area to five.[50] The San Antonio missions usually contained fewer than 300 Indians. Many of those who lived at the mission had nowhere else to go, and belonged to small tribes that have since become extinct.[51]

The Spanish government believed that settlers would defend their property, alleviating the need for some of the presidios.[52] Texas was an unappealing prospect for most settlers, however, due to the armed nomadic tribes, high costs, and lack of precious metals.[51] In 1731, the Spanish government resettled 55 people, mostly women and children, from the

As the first settlers of the municipality, the Islanders and their descendants were designated

Spain discouraged manufacturing in its colonies and limited trade to Spanish goods handled by Spanish merchants and carried on Spanish vessels. Most of the ports, including all of those in Texas, were closed to commercial vessels in the hopes of dissuading smugglers. By law, all goods bound for Texas had to be shipped to Veracruz and then transported over the mountains to Mexico City before being sent to Texas. This caused the goods to be very expensive in the Texas settlements.[59] Settlers were often forced to turn to the French for supplies, as the fort at Natchitoches was well-stocked and goods did not have to travel as far. Without many goods to trade, however, the remaining Spanish missionaries and colonists had little to offer the Indians, who remained loyal to the French traders.[60]

Peace with France

Indians confirmed in 1746 that French traders periodically arrived by sea to trade with tribes in the lower

The

On November 3, 1762, as part of the Treaty of Fontainebleau, France ceded the portion of Louisiana west of the Mississippi River to Spain. Spain had assisted France against Britain in the Seven Years' War, and lost both Manila and Havana to the British. Although the Louisiana colony was a financial liability, King Carlos III of Spain reluctantly accepted it, as that meant France was finally ceding its claim to Texas.[67] At the Treaty of Paris on February 10, 1763, Great Britain recognized Spain's right to the lands west of the Mississippi. Great Britain received the remainder of France's North American territories, and Spain exchanged some of their holdings in Florida for Havana.[68]

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1740 | 437–560 |

| 1762 | 514–661 |

| 1770 | 860 |

| 1777 | 1,351 |

| 1780 | 1,463 |

With France no longer a threat to Spain's North American interests, the Spanish monarchy commissioned the

As a result of Rubí's recommendations, Presidio de San Agustín de Ahumada was closed in 1771, leaving the Texas coast unoccupied except for La Bahía. In July 1772, however, the governor of Texas heard rumors that English traders were building a settlement in the area of the Texas coast that had been abandoned.[75] The commander of La Bahía was sent to find the settlement, but saw no sign of other Europeans. His expedition did, however, trace the San Jacinto River to its mouth where it emptied into Galveston Bay.[76]

Founding of Nacogdoches

The 500 Hispanic settlers who had lived near Los Adaes had to resettle in San Antonio in 1773.[77] In the six years between the inspection and the removal of the settlers, the immigrant population of East Texas had increased from 200 Europeans to 500, a mixture of Spanish, French, Indians, and a few blacks. The settlers were given only five days to prepare to relocate to San Antonio. Many of them perished during the three-month trek and others died soon after arriving.[78]

After protesting, they were permitted in the following year to return to East Texas, but only as far as the Trinity River, 175 miles (282 km) from Natchitoches. Led by Antonio Gil Y'Barbo, the settlers founded the town of Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Bucareli "where the trail from San Antonio to Los Adaes crossed the Trinity."[77] The settlers helped smuggle contraband goods from Louisiana to San Antonio, and also helped the soldiers with coastal reconnaissance.[79]

In May 1776, King Carlos III created a new position, the

In 1779, the Comanches began raiding the Bucareli area, and the settlers chose to move further east to the old mission of Nacogdoches, where they founded the town of the same name. The new town quickly became a waystation for contraband.[77] The settlers did not have authorization to move, and no troops were assigned to protect the new location until 1795.[69]

Conflict with the Native Americans

Apache raids

The tribes traded freely, and soon many had acquired French guns, while others had traded for Spanish horses. Tribes without access to either resource were left at a disadvantage. The

The threat of Apache raids led to a constant state of unease in San Antonio, and some families left the area, while others refused to leave the safety of the town to tend their livestock.

The Apache were coming under increased pressure from the Comanche advancing from the north and sought peace with the Spanish. A peace was declared in August 1749, when a group of

Apaches shunned the mission, and on March 16, 1758, a band of Comanche, Tonkawa, and Hasinai warriors, angry that the Spaniards were assisting their Apache enemies, pillaged and burned the mission, killing eight people.[94] The San Sabá mission was the only Spanish mission in Texas to be completely destroyed by Indians, and it was never rebuilt.[95] Although the Indian force had 2000 members, they chose not to attack the fort.[94]

The Spanish government refused to abandon the area completely out of fear that such an action would make them appear weak. While they planned a response, Indians raided the San Saba horse herd, stealing all of the horses and pack mules and killing 20 soldiers.[96] In October 1759, Spain sent the San Sabá commander, Colonel Diego Ortiz Parrilla, on an expedition north to the Red River to avenge the attack. The tribes were forewarned and led Parrilla's army to a fortified Wichita village, surrounded by a stockade and a moat, where natives brandished French guns and waved a French flag. After a skirmish in which 52 Spaniards were killed, wounded, or deserted, the Spanish retreated.[94] The San Sabá presidio was replaced with a limestone fortress and a moat, but the Comanches and their allies remained close and killed any soldiers who ventured out. By 1769, Spain abandoned the fort.[97]

In 1762, missionaries established two unauthorized missions south of San Sabá, in the Nueces River valley. For several years the Apache lived in the missions most of the year, but left in winter to hunt buffalo. One of the missions closed in 1763, when the Apache never returned from their hunt.[98] The surviving mission closed in January 1766, after a force of 400 natives from the northern tribes attacked, killing 6 Apaches and taking 25 captives as well as all the livestock in the valley. Forty-one Spanish troops and their small cannon ambushed the northern tribes as they returned to East Texas. Before the Spanish were forced to retreat, over 200 Indians and 12 Spanish soldiers died.[99] After the battle, the Apache refused to return to the mission and returned to raiding near San Antonio. Raids by the northern tribes decreased, however.[100]

Comanche

The first recorded contact between the Comanche and the Spanish in Texas was in 1743 when a small band of Comanche visited San Antonio. The Comanche were expanding southward from Colorado and pushing the Apache off the Great Plains. About 1750 they became the dominant power in the northwestern one-half of Texas, called the Comanchería (Spanish for "Comanche lands"), and maintained their dominance for 100 years.[101] Through a combination of diplomacy and war, the Comanche established an extensive long-distance trade network and spread their language and culture among allied Indian tribes. Initially, the Spanish in Texas called them the norteños (northerners) a collective term for the Wichita and other Indian tribes in northern Texas. [102]

The Comanche were divided into the western bands which primarily raided and traded in New Mexico and the eastern banks which primarily raided and traded in Texas. For much of the 1770s, the Comanche raided in New Mexico.[103] The Comanche were defeated in a battle in Colorado in 1779 by a Spanish army led by New Mexico governor Juan Bautista de Anza and redirected their activities to the weakly defended Texas. During the same time period the Apaches, who had been stockpiling guns received from the Karankawas, returned to raiding settlements in Texas, violating their peace treaty.[104] The Comanche promptly declared war on the Apache.[103]

Gálvez became the viceroy of New Spain in 1785.[105] Gálvez ordered that the Native Americans be encouraged to use alcohol, which they could only get through trading, and that the firearms they were traded be poorly made so that they would be awkward to use and easy to break.[106] His policies were never implemented, as Spain did not have the money to provide gifts such as those to the tribes.[107] Instead, the Spanish negotiated a treaty with the Comanche in late 1785.[108] The treaty promised annual gifts to the Comanches, and the peace it brought lasted for the next 30 years.[109] By late 1786, northern and western Texas were secure enough that Pedro Vial and a single companion safely "pioneered a trail from San Antonio to Santa Fe," a distance of 700 miles (1,100 km).[110]

The Comanches were willing to fight the enemies of their new friends, and soon attacked the Karankawa. Over the next several years, the Comanches killed many of the Karankawa in the area and drove the others into Mexico.[111] By 1804, very few natives lived on the barrier islands, where the Karankawa had made their home.[112] In January 1790, the Comanche also helped the Spanish fight a large battle against the Mescalero and Lipan Apaches at Soledad Creek west of San Antonio.[113] Over 1,000 Comanche warriors participated in raids against the Apache in 1791 and 1792, and the Apache were forced to scatter into the mountains in Mexico.[114] In 1796, Spanish officials began an attempt to have the Apache and Comanche coexist in peace, and over the next ten years the intertribal fighting declined.[115]

Karankawa difficulties

In 1776, Native Americans at the Bahia missions told the soldiers that the Karankawas had massacred a group of Europeans who had been shipwrecked near the mouth of the Guadalupe River.[116] After finding the remains of an English commercial frigate, the soldiers warned the Karankawa to refrain from attacking seamen. The soldiers continued to explore the coast, and reported that foreign powers could easily build a small settlement on the barrier islands, which were difficult to access from the mainland, and then ascend the Trinity or San Jacinto Rivers into the heart of Texas. Captain Luis Cazorla, the commander of the La Bahía presidio, recommended that Spain build a small fort on the barrier islands and provide a shallow-draft vessel to continually reconnoiter the coast. The fort would be both a deterrent to the more bloodthirsty tribes and to the English. The Spanish government, fearful of smuggling, declined to give permission for a port or a boat on the Texas coast.[117]

De Croix was unimpressed with his new province, complaining that,

"'A villa without order, two presidios, seven missions, and an errant population of scarcely 4,000 persons of both sexes and all ages that occupies an immense desert country, stretching from the abandoned presidio of Los Adaes to San Antonio, ... does not deserve the name of the Province of Texas ... nor the concern entailed in its preservation.'"[118]

Despite his distaste for the area, he increased the number of troops in the interior provinces by 50% and created units of "light troops" which did not carry all of the heavy gear and could fight on foot. His administration also attempted to build alliances with native troops, and planned to work with the Comanche and the Wichita to wipe out the Apache raiders.[119] The plan was shelved when Spain entered the American Revolution as an ally of the French and the American revolutionaries and money and troops were diverted to attacking Florida instead of exterminating the Apaches.[120][121] After soldiers in Coahuila aligned with the Mescaleros against the Lipan Apaches, however, Spain was able to sign a peace treaty with the Lipans. The Comanches were also becoming more brazen, attacking Presidio La Bahía in 1781, where they were repulsed.[120]

After hearing that Englishman George Gauld had surveyed the Gulf Coast all the way to Galveston Bay in 1777, Bernardo de Gálvez appointed a French engineer, Luis Antonio Andry, to conduct a similar survey for Spain.[122] Andry finished his survey in March 1778, and anchored off Matagorda Bay after running dangerously low on provisions. Over a period of days, the Karankawa lured a few men at a time from the ship with offers of assistance and killed all but one, a Mayan sailor named Tomás de la Cruz.[123] The Karankawa also burned the ship and the newly created map, possibly the first detailed Spanish map of the Texas-Louisiana coast.[124] Several months later, the Native Americans living at Mission Rosario, near La Bahía, escaped to join the Karankawa, and together they began raiding livestock and harassing settlers. The governor pardoned many of the fugitives, and most of them returned to the mission.[123] The Karankawa continued to cause difficulties for the Spanish, and in 1785 the interim commandant-general, Joseph Antonio Rengel, noted that they were unable to explore in the Matagorda Bay region as long as the Karankawa held it.[125]

The Spanish again arranged for their coastline to be mapped, and in September 1783, José de Evia left Havana to chart the coastline between Key West and Matagorda Bay.[126] During his journey, Evia gave Galveston Bay its name, in honor of his sponsor, De Gálvez.[127] Evia later mapped the Nuevo Santander coast between Matagorda Bay and Tampico, part of which later belonged to Texas.[128]

In 1791 and 1792, Fray José Francisco Garza befriended some of the Karankawa and other native peoples.

Conflict with the United States

The Second Treaty of Paris in 1783 ended the American Revolution and established the United States of America.[132] The treaty extended the new country's western boundary to the Mississippi River[133] and within the first year after it was signed 50,000 American settlers crossed the Appalachian Mountains. As it was difficult to return east across the mountains, the settlers began looking toward the Spanish colonies of Louisiana and Texas to find places to sell their crops.[132] Spain closed the mouth of the Mississippi to foreigners from 1784 until 1795 despite Thomas Jefferson's 1790 threat to begin an Anglo-Spanish war over the matter.[134][135] Americans risked arrest to come to Texas, many of them desiring to capture wild mustangs in West Texas and trade with the Indians.[136] In 1791, Philip Nolan became the first Anglo-American known to pursue horse-trading in Texas, and he was arrested several times for being within Spain's borders.[137] The Spanish feared that Nolan was a spy, and in 1801 they sent 150 troops to capture Nolan and his party of 6 men; Nolan was killed during the ensuing battle.[138] By 1810, many Americans were trading guns and ammunition to the Texas Indians, especially the Comanche, in return for livestock. Although some chiefs refused to trade with them and reported their movements to Spanish authorities, other bands welcomed the newcomers.[139][140] A drought made rangeland scarce and stopped the Comanche's herds from increasing. To meet the American demand for livestock, the Comanche turned to raiding the area around San Antonio.[140]

The Spanish government believed that security would come with a larger population, but was unable to attract colonists from Spain or from other New World colonies.

In 1799, Spain gave Louisiana back to France in exchange for the promise of a throne in central Italy. Although the agreement was signed on October 1, 1800, it did not go into effect until 1802. The following year,

The United States insisted that its purchase also included most of West Florida and all of Texas.[148] Thomas Jefferson claimed that Louisiana stretched west to the Rocky Mountains and included the entire watershed of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers and their tributaries, and that the southern border was the Rio Grande. Spain maintained that Louisiana extended only as far as Natchitoches, and that it did not include West Florida or the Illinois Territory.[150]

Texas was again considered a buffer province, this time between New Spain and the United States. In 1804, Spain planned to send thousands of colonists to increase the number of residents in Texas (then at 4,000 Hispanic inhabitants). The plan was cancelled as the government did not have the money to relocate the settlers.

King Charles IV of Spain ordered data compiled to determine the true boundary.[152] Before the border was settled, both sides led armed excursions into the disputed areas, and Spain began increasing the number of troops stationed in Texas. By 1806, the number had doubled, with over 883 stationed in and around Nacogdoches.[153] At the end of 1806, local commanders negotiated a temporary agreement in which neither the Spanish nor the Americans would venture into the area between the Sabine River and Arroyo Hondo.[154] This neutral ground quickly became a haven for lawlessness[155] and it did not stop individuals from crossing the boundary.[156] While on a mission for the United States Army to explore some of the disputed areas of the Louisiana Purchase[157] Zebulon Pike was arrested by the Spanish while camping on the Rio Grande and escorted back to Natchitoches. Although his maps and notes were confiscated, Pike was able to recreate most of it from memory. His glowing comments about Texas lands and animals made many Americans yearn to control the territory.[156]

End of Spanish period

In May 1808, Napoleon forced King

During this time of turmoil, it was unclear who actually governed the colonies: Joseph I, the shadow government representing Ferdinand VII, the colonial officials, or revolutionaries in each province.

Although officially neutral during the Mexican War of Independence, the United States allowed rebels to trade at American ports

Another revolutionary, José Manuel Herrera, created a government on Galveston Island in September 1816 which he proclaimed part of a Mexican Republic.[169] A group of French exiles in the United States attempted to create their own colony on the Trinity River, known as Le Champ d'Asile. The exiles planned to use the colony as a base to liberate New Spain and then free Napoleon from St. Helena. They abandoned the colony shortly and returned to Galveston.[170]

On February 22, 1819, Spain and the United States reached agreement on the

In 1819, James Long led the Long Expedition to invade Texas. He declared Texas an independent republic, but by the end of the year his rebellion had been quelled by Colonel Juan Ignacio Pérez and his Spanish troops. The following year Long established a new base near Galveston Bay "to free Texas from 'the yoke of Spanish authority... the most atrocious despotism that ever disgraced the annals of Europe.'"[173] His basis for a rebellion was soon gone, however.

On February 24, 1821, Agustín de Iturbide launched a drive for Mexican Independence. Texas became a part of the newly independent nation without a shot being fired.[173]

Spanish Texas population

| Year | Pop Spaniards/Criollo | % pop | Mestizo, Castizo and other castes | % pop | Amerindians | % pop | Slaves | % pop | Total Population | Inhabitants per Sq.League |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1682 | 129 (Coulson and Joyce estimates for Ysleta Mission, first Spanish foundation in modern-day Texas)[175] |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 1731 | 500[176] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 1742 (Peter Gerhard estimations) | 1,800[177] | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1,290 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3,090 | N/A |

| 1761 | About 1,200[178] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 1777 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | -1%[178] | 3,103[178][177] | N/A |

| 1780 | 2,000 | 50%[179] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4,000[177] | N/A |

| 1790 (Revillagigedo census)[180] |

1,326 | 41% | 1,083 | 32% | 912 | 27% | N/A | 2.2% | 3,169[178] - 3,334 | N/A |

| 1800 | 4,800 (Juan Bautista Elguézabal census)[177] |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 1810 | 5,000[181] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3,334 (Fernando Navarro y Noriega estimation, included in his work Memoria sobre la población de Nueva España)[182] |

N/A |

| 1821 | 2,500[Note 2][183] | 10%[184] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 1830 | 3,000[175] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Legacy

Spanish control of Texas was followed by Mexican control of Texas, and it can be difficult to separate the Spanish and Mexican influences on the future state. The most obvious legacy is that of the language;[185] the state's name comes from the Spanish rendering of an Indian word.[186] Every major river in modern Texas, except the Red River, has a Spanish or Anglicized name, as do 42 of the state's 254 counties and numerous towns also bear Spanish names.[185] Even many of the words that have been incorporated into American English, such as barbecue, canyon, ranch, and plaza, come from Spanish words.[186] An additional obvious legacy is that of Roman Catholicism. At the end of Spain's reign over Texas, virtually all inhabitants practiced the Catholic Christian religion, and it is still practiced in Texas by a large number of people.[187] The Spanish missions built in San Antonio to convert Indians to Catholicism have been restored and are a National Historic Landmark.[188]

The landscape of Texas was changed as a result of some Spanish policies. As early as the 1690s, Spaniards brought European livestock, including cattle, horses, and mules, with them on their expeditions throughout the province. Some of the livestock strayed or stayed behind when the Spanish retreated from the territory in 1693, allowing the Indian tribes to begin loosely managing herds of the animals.[189] These herds grazed heavily on the native grasses, allowing mesquite, which was native to the lower Texas coast, to spread inland. Although the introduced livestock were able to adapt to the changing conditions, the buffalo had a more difficult time grazing among the new vegetation, beginning the decline in their numbers.[190] Spanish farmers also introduced tilling and irrigation to the land, further changing the landscape.[191] Spanish architectural concepts were also adopted by those in Texas, including the addition of patios, tile floors and roofs, arched windows and doorways, carved wooden doors, and wrought iron grillwork.[192]

Although Texas eventually adopted much of the Anglo-American legal system, many Spanish legal practices were retained. Among these was the Spanish model of keeping certain personal property safe from creditors. Texas implemented the first homestead exemption in the United States in 1839, and its property exemption laws are now the most liberal in the United States.[193] Furthermore, Spanish law maintained that both husband and wife should share equally in the profits of marriage, and, like many other former Spanish provinces, Texas retained the idea of community property rather than use the Anglo laws in which all property belonged to the husband.[194] Furthermore, Spanish law allowed an independent executor to be named in probate cases who is not required to gain court permission for each act not explicitly listed in the testament. Texas retained this idea, and it has eventually spread to other states, included Arizona, Washington, and Idaho.[194] In other legal matters, Texas kept the Spanish principle of adoption, becoming the first U.S. state to allow adoption.[195]

See also

- Spanish Texas topics

- Pre-statehood history of Texas

- List of colonial and Mexican governors of Texas

References

- ^ a b Edmondson (2000), p. 6.

- ^ a b Edmondson (2000), p. 10.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 26.

- ^ "Handbook of Texas Online", Robert S. Weddle, "Carvajal Y De La Cueva, Luis De," accessed 13 August 2016, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fcadn

- JSTOR 23667140.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 149.

- ^ Weber (1992), pp. 151–152.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 83.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 153.

- ^ a b Chipman (1992), p. 87.

- ^ a b Chipman (1992), p. 88.

- ^ a b Weber (1992), p. 162.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 18.

- ^ a b c Chipman (1992), p. 89.

- ^ a b c Weber (1992), p. 154.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 91.

- ^ Chipman (1992), pp. 93–94.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 97.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 98.

- ^ a b Weber (1992), p. 155.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 100.

- ^ a b Weber (1992), p. 158.

- ^ a b Chipman (1992), p. 107.

- ^ a b Chipman (1992), p. 110.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), pp. 8–9.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 159.

- ^ a b c d e Weber (1992), p. 160.

- ^ a b Chipman (1992), p. 111.

- ^ a b Chipman (1992), p. 112.

- ^ a b c Chipman (1992), p. 113.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 115.

- ^ de la Teja, Jesús F. (June 15, 2010). "New Philippines". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 116.

- ^ a b Weber (1992), p. 163.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 117.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 118.

- ^ Weber (1992), pp. 165–166.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 166–167.

- ^ a b c Weber (1992), p. 167.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 120.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 121.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 123.

- ^ a b Weber (1992), p. 168.

- ^ a b c Chipman (1992), p. 126.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 128.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 129.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 186.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 187.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 130.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 131.

- ^ a b Weber (1992), p. 192.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 135.

- ^ Weber (1993), p. 193.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 136.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 137.

- ^ a b Chipman (1992), p. 139.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 140.

- ^ a b Chipman (1992), p. 145.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 175.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 173.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 164.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 184.

- ^ Chipman (1992), pp. 165, 166.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 168.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 195.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 194.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 198.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 199.

- ^ a b Chipman (1992), p. 187.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 188.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 173.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 181.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 211.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 184.

- ^ Weddle (1995), p. 79.

- ^ Weddle (1995), p. 80.

- ^ a b c Weber (1992), p. 222.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 186.

- ^ Weddle (1995), p. 86.

- ^ Weber (1992), pp. 224–225.

- ^ a b Weddle (1995), p. 88.

- ^ Weddle (1995), p. 89.

- ^ a b c d Weber (1992), pp. 127, 188, 193.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 133.

- ^ Anderson (1999), p. 111.

- ^ Anderson (1999), p. 113.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 150.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 151.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 152.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 153.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 156.

- ^ Anderson (1999), p. 120.

- ^ Chipman (1992), pp. 158, 159.

- ^ a b c d Weber (1992), p. 189.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 161.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 162.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 191.

- ^ Anderson (1999), p. 124.

- ^ Anderson (1999), p. 125.

- ^ Anderson (1999), p. 126.

- ISBN 978-0-300-15117-6.

- JSTOR 970405.

- ^ a b Anderson (1999), p. 139.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 198.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 228.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 229.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 230.

- ^ Weddle (1995), p. 163.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 199.

- ^ Weber (1992), pp. 234–235.

- ^ a b c Weddle (1995), p. 164.

- ^ a b Weddle (1995), p. 167.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 200.

- ^ Anderson (1999), p. 140.

- ^ Anderson(1999), p. 141.

- ^ Weddle (1995), p. 81.

- ^ Weddle (1995), p. 82.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 193.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 226.

- ^ a b Chipman (1992), p. 192.

- ^ Thonhoff (2000), p. 25.

- ^ Weddle (1995), pp. 137, 150, 152.

- ^ a b Weddle (1995), p. 155.

- ^ Weddle (1995), p. 156.

- ^ Weddle (1995), p. 161.

- ^ Weddle (1995), p. 169.

- ^ Weddle (1995), p. 176.

- ^ Weddle (1995), p. 187.

- ^ Weddle (1995), p. 165.

- ^ Weddle (1995), p. 166.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 202.

- ^ a b Chipman (1992), p. 196.

- ISBN 0-8078-2429-1

- ^ Lewis (1998), p. 15

- ^ Lewis (1998), p. 22

- ^ a b Weber (1992), p. 296.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 213.

- ISBN 0-8173-0880-6

- ^ Anderson (1999), p. 252.

- ^ a b c d Anderson (1999), p. 253.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 280.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 205.

- ^ Chipman (1992), pp. 205–206.

- ^ a b Chipman (1992), p. 206.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 207.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 209.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 281.

- ^ a b Weber (1992), p. 291.

- ^ Weddle (1995), p. 194.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 292.

- ^ a b Weber (1992), p. 295.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 223.

- ^ Owsley & Smith (1997), p. 36

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 224.

- ^ Owsley & Smith (1997), p. 38

- ^ a b Chipman (1992), p. 226.

- ISBN 0-8061-3046-6

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 275.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 297.

- ^ Lewis (1998), p. 34

- ^ Owsley & Smith (1997), p. 40

- ^ Owsley & Smith (1997), p. 41

- ^ Lewis (1998), p. 80

- ^ Lewis (1998), p. 37

- ^ a b c d e Weber (1992), p. 299.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 236.

- ^ Owsley & Smith (1997), p. 58

- ^ Anderson (1999), p. 254.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 238.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 239.

- ^ Lewis (1998), p. 124

- ^ Lewis (1998), p. 136

- ^ a b c Weber (1992), p. 300.

- ^ Lewis (1998), p. 145

- ^ a b David P. Coulson; Linda Joyce (August 2003). "United States state-level population estimates: Colonization to 1999" (PDF). USDA. p. 44.

- ^ Weber, David J. (1993), The Spanish Frontier in North America, Yale Western Americana Series, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-05198-0

- ^ a b c d Alicia Vidaurreta Tjarks. "Comparative Demographic Analysis of Texas, 1777-1793*" (PDF). p. 8.

- ^ a b c d Chipman (1992), pp. 205–206, 194

- ISBN 978-1-118-61772-4.

- ^ "New Spain (Mexico), 1790 Statistics Charts". 24 December 2013. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ISBN 978-968-12-0191-3. Retrieved 6 October 2021. Published on Elena Gallego. Rare Books.

- ^ "Texas is given a population of 3,334". Archived from the original on 2021-10-08. Retrieved 2021-10-08.

- ^ Marcela Terrazas y Basanate (January 2008). "Las fronteras septentrionales de México ante el avance norteamericano, 1700-1846". Península. 3 (2): 149–162. Retrieved 6 October 2021. Península vol.3 no.2 Mérida January 2008

- ^ Enrique Rajchenberg S.; Catherine Héau-Lambert. "El desierto como representación del territorio septentrional de México" (PDF). p. 7. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ a b Chipman (1992), p. 242.

- ^ ISBN 1-57168-197-3

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 259.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 255.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 246.

- ^ Anderson (1999), p. 130.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 247.

- ^ Maxwell (1998), p. 62

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 254.

- ^ a b Chipman (1992), p. 253.

- ^ Chipman (1992), p. 252.

Notes

- Cabeza de Vaca and three companions wandered lost along the Texas Gulf Coast and the Rio Grande between 1528 and 1535 trying to find their way back to a Spanish settlement after they survived the ill-fated Narváez expedition in Florida. De Vaca made the first contact with Indians in Texas in November 1528. Chipman (1992), p. 11.

- ^ The Mexican War of Independence caused a loss of population throughout the country, including Texas. On the other hand, Spanish Texas consisted of East Texas and the part of Louisiana bordering Texas, where Los Adaes was located. West Texas belonged to Santa Fe de New Mexico, which included El Paso. In 1821, El Paso and the surrounding area had 8,000 Hispanics.[citation needed]

Sources

- Anderson, Gary Clayton (1999), The Indian Southwest, 1580–1830: Ethnogenesis and Reinvention, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0-8061-3111-X

- Chipman, Donald E. (2010) [1992], Spanish Texas, 1519–1821 (revised ed.), Austin: University of Texas Press, ISBN 978-0-292-77659-3

- Edmondson, J. R. (2000), The Alamo Story: From History to Current Conflicts, Plano: Republic of Texas Press, ISBN 1-55622-678-0

- Thonhoff, Robert H. (2000), The Texas Connection With The American Revolution, Austin: Eakin Press, ISBN 1-57168-418-2

- ISBN 0-300-05198-0

- Weddle, Robert S. (1995), Changing Tides: Twilight and Dawn in the Spanish Sea, 1763–1803, Centennial Series of the Association of Former Students Number 58, College Station: Texas A&M University Press, ISBN 0-89096-661-3

Further reading

- Chipman, Donald E.; Joseph, Harriett Denise (1999). Notable Men and Women of Spanish Texas. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-79316-3.

- Martinez de Vara, Art (2020). Tejano Patriot: The Revolutionary Life of Jose Francisco Ruiz, 1783 - 1840. ISBN 978-1-62511-058-9.