Military history of Spain

The

Spain's

The Napoleonic Wars changed Spanish military history dramatically; the Peninsular War saw the development of guerrilla warfare against the occupying French forces. The collapse of central Spanish authority resulted in successful wars of independence amongst Spain's American colonies, drastically reducing the size of her empire, and in turn led to a sequence of civil wars in Spain itself, many fought by frustrated veterans of the French and colonial campaigns. Attempts to reassert imperial power during the mid-19th century, enabled by the development of the steam frigate ultimately failed, leading to the collapse of the remnants of Spain's empire in the Americas and Asia in 1898 at the hands of a rising power, the United States of America. The political tensions that had driven the Carlist Wars remained unchecked, spilling over once again in the Spanish Civil War of 1936–39. Bringing a foretaste of the tactics of the Second World War, several nations used the conflict as a testing ground for new aerial and armoured warfare tactics. In the post-war period, Spain has increasingly turned away from the last remaining colonial conflicts in Africa, and played a growing modern military role within the context of the NATO alliance.

The Classical period: the rise of Rome

In the

After the expulsion of the Carthaginians from Hispania in the

Under Roman rule, Hispania contributed, like the rest of empire, to the Roman military, providing both

The collapse of Rome and barbarian invasions

During the third through 6th centuries, the Roman Empire was beset by numerous barbarian invaders, mostly

The first barbarians to settle were the Suevi, whose king Hermeric, a former foederatus of Rome, ratified a peace with the local Hispano-Roman population in 438. Weary of fighting, Hermeric abdicated in favour of his son Rechila. As the Visigothic kingdom expanded into Iberia, expelling the Vandals and Alans, the Suevi expanded their own realm as far south as Mérida. In 456, the new Catholic king, Rechiar, died in battle with the Visigoth king Theodoric II and the Suevi kingdom began to retreat under Gothic pressure. Beset by internal political conflict, the Suevi capitulated to the Visigoths in 585. Some resistance was maintained for a few years, but soon the last of Suevi resistance was erased.

The Visigoths consolidated a kingdom spanning most of Iberia and Gaul. For the next two centuries, they warred not only amongst themselves in a sequence of succession crises – which followed the election of a new king after every royal death,

Islamic conquest and Reconquista

For almost seven hundred years, Spain was the battleground for the opposing forces of the Islamic

The Islamic conquest was only very slowly undone, over the course of seven centuries in what the Christians of Spain called the

Despite a resurgence during the 10th century, the

Unification of Castile and Aragon

Late medieval Spain was divided into the three Christian kingdoms of Navarre, Castile and Aragon, alongside the small, last remaining Islamic state of Granada. The civil wars and conflicts of the late 14th and early 15th century would result in the unification of the Christian kingdoms; combined with advances in naval technology, this would pave the way for the rise of Spain as a dominant European power.

Castile, a medium-sized kingdom with a strong maritime tradition, was plunged into civil war following the death of

The threat of internal stability remained until the marriage of

The conquest of the Americas and the beginnings of empire

After

The most dramatic impact of Spanish military power, however, lay in the

Spain had one of its worst military defeats in the War by Fire and blood (also known as the

The Spanish were to fare less well against the less centralised societies of southern Chile, however, particularly once local forces began to adapt to, or actually adopt similar military technologies. Although Pedro de Valdivia was able to successfully invade Chile in 1540, the first great rebellion of the Arauco wars was to begin only 1553 later, marking the beginning of a conflict that would last until the 19th century.[12] Spanish forces, operating at huge distances from their European or even Caribbean centres of power, were frequently available in small numbers; Valdivia had great difficulty in recruiting even the 150 Spanish soldiers he used to invade Chile, and the frequent reversals during the Arauco wars led to losses that often took several years to replace. As time progressed, the advantages of the Spanish began to increasingly centre on their access to early modern firearms, especially the musket, rather than the technologies that had won them their early successes.[13]

The 16th and 17th centuries, Spain's 'Golden Age'

During the 16th century,

By one modern estimate, the Spanish army in 1625 was 230,000 regulars (80,000 in field armies, 150,000 in garrisons), exclusive of naval personnel and militia.[17] By another the Spanish army grew in size from around 20,000 in the 1470s, to around 300,000 by the 1630s during the Thirty Years' War that tore Europe apart, requiring the recruitment of soldiers from across Europe.[18] King Philip IV himself stated in 1626: "Last year, 1625, we had nearly 300,000 infantry and cavalry in our pay, and over 500,000 men of the militia under arms, whilst the fortresses of Spain are being put into a thorough state of defence. The fleet rose at one time in 1625 to 108 ships of war at sea, without counting the vessels at Flanders, and the crews are the most skillfull mariners this realm ever possessed. This very year of 1626 we have had two royal armies in Flanders and one in the Palatinate, and yet all the power of France, England, Sweden, Venice, Savoy, Denmark, Holland, Brandenburg, Saxony, and Weimar could not save them from our victorious arms."[19]

With such numbers involved, Spain had trouble funding the war efforts on so many fronts. The non-payment of troops led to many mutinies and events such as the Sack of Antwerp (1576), when unpaid tercio units looted the Dutch city. Spain's holdings in Italy and the Low Countries contributed large amounts of men and treasure to the empire's army: each province was allotted a number of troops it had to pay for (including the ethnic Spanish garrisons) and recruits it had to provide. Troops were generally sent outside of the areas they were recruited in.[20] From 1635 to 1659, the Duchy of Milan provided 100,000 soldiers to the Spanish army, while the Kingdom of Naples provided 53,500 (plus a naval expedition) from 1631 to 1636 alone.[21]

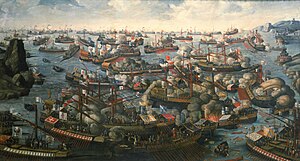

In the east, Habsburg Spain fought alongside other Christian allies against the

Spain fought the

The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) drew in Spain alongside most other European states. Spain entered the conflict with a strong position, but the ongoing fighting gradually eroded her advantages; first Dutch, then Swedish innovations had made the tercio more vulnerable, having less flexibility and firepower than its more modern equivalents.[25] Nevertheless, Spanish armies continued to win major battles and sieges throughout this period across large swathes of Europe. French entry into the war in 1635 put additional pressure on Spain, with the French victory at the Battle of Rocroi in 1643 being a major boost for the French, though it proved far from decisive in the long-running Franco-Spanish War (1635–1659). By the signing of the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, which brought an end to most of the fighting, Spain was clearly exhausted. Politics too had begun to count against Spain. While Spain was fighting France, Portugal – which had been under personal union with Spain for 60 years – acclaimed John IV of Braganza as king in 1640.

Spain was forced to accept the independence of the

European rivalry in the 18th century

The centre of Spanish military power shifted dramatically in the early 18th century. The War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) was both a civil and international war in which the French backed the Bourbon contender for the Spanish throne and an alliance led by Austria, the Netherlands and Britain backed the Habsburg contender while a divided Spain fought on both sides. The war secured the Spanish throne for the Bourbon Philip as Philip V of Spain at the Peace of Utrecht but in the war's settlement, Spain had to give up the Spanish Netherlands, Naples, Milan, Sardinia, Sicily, Gibraltar and Menorca to the Habsburg allies. Spain's defeat by the combined alliance of France, Britain, the Netherlands and Austria in the War of the Quadruple Alliance (1718–1720) confirmed the decline from her former dominance, whilst the successful deployment of the Britain's Royal Navy into the Mediterranean, by exploiting the fortress of Gibraltar, gained in 1704 by an Anglo-Dutch force during the war of succession, would create considerable difficulties in the following years.[27]

Globally, Spain remained an important naval and military power, depending on critical

The huge distances involved in warfare between European powers in the Americas usually counted in favour of the defenders. Attacks on Spanish possessions, such as the amphibious assaults launched during the War of Jenkins' Ear usually ended in failure as their overstretched forces failed to overcome well led defensive actions. Spain's

The Napoleonic Wars and the loss of the Americas

The

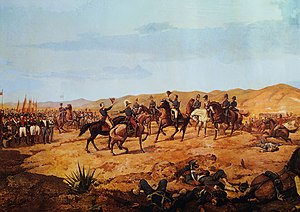

The events in mainland Spain had extensive consequences for her empire. Spain's colonies in the Americas had shown an increasing independence in the years running up to the

19th century Carlist Wars and the final days of empire

In the aftermath of the

Under

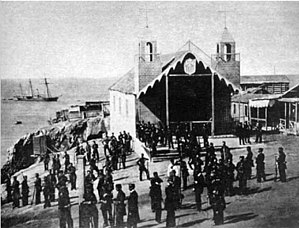

Spain faced a sequence of challenges across her colonies in the second half of the century that would result in a total defeat of empire at the hands of the growing power of the United States. Spain's colony of

Early 20th century and the Civil War

Although Spain

In 1931, following the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic, the armed forces of the Spanish Kingdom became the Spanish Republican Armed Forces. The

army.The civil war was marked by the

Weakened and politically still fragile, Spain

The post-war period

In the post-war period, Spain was initially still heavily influenced by events in North Africa, particularly surrounding its colony of

From the 1950s onwards, however, Spain began to build increasingly close links with the U.S. armed forces. The

Spanish military cultural legacy

Historically, in addition to Latin military terms that came down from Roman times into modern Spanish through the language, the Spanish adopted a number of Arabic military terms from their Muslim rivals. Subsequently, a number of Spanish military terms have been adopted into French, English and other languages.

| Spanish term | Original language | Original meaning | Modern English term | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| alcaide | Arabic kaid

|

master, leader | Medieval Spanish military commander or castellan. | |

alcazaba

|

Arabic al-casbah | walled citadel | ||

| alcázar | Arabic al-qasr | castle or palace | Could refer to a residence, citadel, or hilltop fortress. | |

| alférez | Arabic | horseman | Used in medieval Castile-León and Navarre to denote the standard-bearer and commander of the royal military household. In modern usage in Spain and Equatorial Guinea, a second lieutenant. | |

| almirante | Arabic amir-al-bahr | commander of the seas | admiral | Adopted in Siculo-Normans and later brought to Spain by the Catalans after Sicily became part of the Aragonese Crown.

|

| armada | Spanish | armed (fem.), later navy, fleet | armada | Came into English usage after the defeat of the Great Armada in 1588.

|

| caballero villano | Spanish | "commoner knight" | A villein who owned a horse and armour and owed cavalry service. | |

coronel

|

Spanish or Italian (colonnello), ultimately Latin (columnella) | diminutive of colonna/columna (column) | colonel | Rank popularised by the tercios. |

| destructor | Spanish | destroyer | A large torpedo gunboat, built in Britain for the Spanish Navy to protect the fleet against torpedo boats, a precursor of the modern destroyer type of ship. | |

| flotilla | Diminutive of Spanish flota, from French flotte | (little) fleet | flotilla | |

| granada | Spanish | pomegranate | grenade | |

guerrilla

|

Spanish | diminutive of guerra (war) | guerrilla | |

| Quinta Columna | Spanish | fifth column | Fifth Column

|

First used during the Spanish Civil War by Emilio Mola at the siege of Madrid in reference to his supporters within the city. |

| tercio | Spanish | third part | Infantry unit developed by Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba during the Italian Wars. |

See also

- Army of Spain (Peninsular War)

- List of wars involving Spain

- Spanish Armed Forces

- Spanish Army

- Spanish Navy

- Spanish Air Force

- Spanish Empire

- Contemporary history of Spain

References

- ^ Syme, 1970.

- ^ Montgomery, p. 12.

- ^ Montgomery, p.11.

- ^ Bury, pp. 286–288.

- ^ Montgomery, p. 13.

- ^ Davis, p. 105.

- ^ O'Callaghan, 2002.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Holmes, p. 258.

- ^ Zaide and Zaide, 2004.

- ^ Diamond, pp. 358–359.

- ^ Villalobos, p. 55.

- ^ Diamond, 1997.

- ^ Davies, 1961

- ^ Wedgewood, p. 31.

- ^ Elton, p. 181.

- ^ Gregory Hanlon. "The Twilight Of A Military Tradition: Italian Aristocrats And European Conflicts, 1560–1800." Routledge: 1997. Page 101.

- ^ Anderson, p. 17.

- ^ Martin Hume. The Court of Philip IV: Spain in Decadence." London 1907, p. 157. Quoting Philip IV's address to the Council of Castile in 1626.

- ^ Hanlon 1997, p. 48.

- ^ Gregory Hanlon. "The Hero of Italy: Odoardo Farnese, Duke of Parma, his Soldiers, and his Subjects in the Thirty Years' War." Routledge: May 2014. Page 116.

- ^ "The galleon evolved in response to Spain's need for an ocean-crossing cargo ship that could beat off corsairs. Pedro de Menéndez, along with Álvaro de Bazán (hero of Lepanto), is credited with developing the prototypes which had the long hull – and sometimes the oars – of a galley married to the poop and prow of a nao or merchantman. Galeones were classed as 1-, 2- or 3-deckers, and stepped two or more masts rigged with square sails and topsails (except for a lateen sail on the mizzenmast). Capacity ranged up to 900 tons or more. Menéndez' San Pelayo of 1565 was a 900 ton galleon which was also called a nao and galeaza. She carried 77 crewmen, 18 gunners, transported 317 soldiers and 26 families, as well as provisions and cargo. Her armament was iron." p. 100 Menéndez: Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, Captain General of the Ocean Sea Albert C. Manucy, published 1992 by Pineapple Press, Inc

- ^ Holmes, p. 235.

- ^ Glyn, p. 4

- ^ Meade, p. 180.

- ^ Anderson, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Simms, p. 135.

- ^ Walton, p. 177.

- ^ Olson, pp. 1121–1122

- ^ Chartrand, pp. 54–56.

- ^ Chartrand, p. 84.

- ^ Laqueur, p. 350.

- ^ a b Gates, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Chandler, p. 164.

- ^ Fletcher, 1991.

- ^ Chasteen, p. 53.

- ^ Palmer, p. 67.

- ^ Fehrenbach, 1970.

- ^ a b Holt, 1967.

- ^ Fernandez, D. Fernando Sánchez Principales Campañas.

- ^ Chapuis, p. 195.

- ^ "Máximo Gómez Báez :: Guerra de los diez años (1868–1878)". Archived from the original on 2007-08-09. Retrieved 2005-12-26..

- ^ Navarro, p. 50.

- ^ Navarro, 1998.

- ^ McEvoy, William P. (May 10, 2003). "Spain During the First World War". FirstWorldWar.com. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ Balfour, p. 142.

- ^ Baxell, 2004.

- ^ Tierney, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Edwards, p. 145.

- ^ Corum 2007, p. 200.

- ^ Casas de la Vega, 1985.

Bibliography

- Anderson, M. S. War and Society in Europe of the Old Regime, 1618–1789. London: Fontana Press. (1988)

- Balfour, Sebastian. Deadly Embrace: Morocco and the road to the Spanish Civil War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (2002)

- Baxell, Richard. British Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War. London: Routledge. (2004)

- Bowen, Wayne H. and Alvarez José E. (eds. and contributors). A Military History of Modern Spain: From the Napoleonic Era to the International War on Terror. Westport, CN: Praeger Security International. (2007) OCLC 154678203.

- Bury, J. B. History of the Later Roman Empire. Macmillan & Co., Ltd.: London (1923)

- Casas de la Vega, Rafael. La última guerra de Africa. Madrid: Servicio de Publicaciones del Estado Mayor del Ejército. (1985) (Spanish)

- Carcedo, Diego Sáenz de Santa María. El general que cambió de bando. Temas de Hoy: Madrid. (2004) ISBN 84-8460-309-1. (Spanish)

- Chandler, David G. The Art of Warfare on Land Penguin Books: London (2000)

- Chapuis, Oscar A History of Vietnam: From Hong Bang to Tu Duc. Greenwood Publishing Group. (1995) ISBN 0-313-29622-7.

- Chartrand, Rene. Gibraltar 1779–83: The Great Siege. Osprey Campaign. (2006)

- Chasteen, John Charles. Americanos: Latin America's Struggle for Independence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (2008) ISBN 978-0-19-517881-4.

- Corum, James S. The Roots of Blitzkrieg: Hans von Seeckt and German Military Reform, Modern War Studies. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. (1992) ISBN 0-7006-0541-X.

- Davies, T. R. The Golden Century of Spain 1501–1621. London: Macmillan & Co. (1961)

- Davis, Paul K. 100 Decisive Battles From Ancient Times to the Present. (1999) ISBN 0-19-514366-3.

- Diamond, Jared. Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. W.W. Norton & Company. (1997) ISBN 0-393-03891-2.

- Edwards, Roger. Panzer, a Revolution in Warfare: 1939–1945. London/New York: Arms and Armour. (1989) ISBN 0-85368-932-6.

- Elton, Geoffrey Rudolph. Reformation Europe, 1517–1559. Oxford: Blackwells. (1999)

- Fehrenbach, Charles W. 'Moderados and Exaltados: the liberal opposition to Ferdinand VII, 1814–1823', Hispanic American Historical Review 50 (1970), 52–69.

- Fernandez, Coronel D. Fernando Sánchez Principales Campañas Recopilación de apuntes sobre la tradición y modernidad del Regimiento de Infantería Inmemorial del Rey nº 1 (Spanish)

- Fletcher, Ian. Waters of oblivion: the British invasion of the Rio de la Plata, 1806–07. Indiana: Indiana University Press. (1991)

- Gates, David. The Spanish Ulcer: A History of the Peninsular War. London: Pimlico. (2002) ISBN 0-7126-9730-6.

- Glyn, Williams. The Prize of All the Oceans. New York: Viking. (1991) ISBN 0-670-89197-5.

- Harvey, Robert. A Few Bloody Noses: The American Revolutionary War. Robinson (2004)

- Homes, George. Europe: Hierarchy and Revolt, 1320–1450. Edinburgh: Fontana Pres. (1984)

- Holt, Edgar. The Carlist Wars in Spain. Dufour Editions: Chester Springs, Pennsylvania. (1967)

- Montgomery, Watt, W. A History of Islamic Spain. Edinburgh: University Press of Edinburgh. (1992)

- Meade, J.E. Principles of Political Economy. SUNY. (1976) ISBN 0-87395-205-7.

- Navarro, José Cantón History of Cuba. The Challenge of the Yoke and the Star. Editorial SI-MAR S. A., Havana, Cuba. (1998) ISBN 959-7054-19-1.

- O'Callaghan, Joseph F. Reconquest and crusade in Medieval Spain. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. (2002), ISBN 0-8122-3696-3.

- Olson, James. Historical Dictionary of the British Empire. Greenwood Publishing Group. (1996) ISBN 0-313-29366-X.

- Palmer, A. W. A Dictionary of Modern History 1789–1945. Penguin Reference Books: London. (1962)

- Simms, Brendan. Three Victories and a Defeat: The Rise and Fall of the First British Empire. Penguin Books (2008).

- Syme, Ronald The Conquest of North-West Spain. Legio VII Gemina 1970

- Tierney, Dominic. FDR and the Spanish Civil War: Neutrality and Commitment in the Struggle That Divided America. Duke University Press. (2007)

- Villalobos, Sergio. A Short History of Chile. Santiago: Editorial Universitaria. (1996)

- Walton, Timothy R. The Spanish Treasure Fleets. Pineapple Press. (2002). ISBN 1-56164-261-4.

- Wedgewood, C. V. The Thirty Years War. London: Methuen. (1981)

- Zaide, Gregorio F. and Sonia M. Zaide Philippine History and Government. Sixth Edition, All-Nations Publishing Company. (2004)