Brian Wilson

Brian Wilson | |

|---|---|

Kenny & the Cadets | |

| Spouses | |

| Website | brianwilson |

| Signature | |

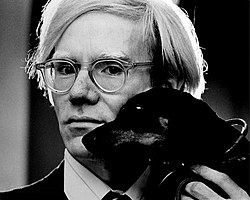

Brian Douglas Wilson (born June 20, 1942) is an American musician, singer, songwriter, and record producer who co-founded the Beach Boys. Often called a genius for his novel approaches to pop composition and mastery of recording techniques, he is widely acknowledged as one of the most innovative and significant songwriters of the 20th century. His best-known work is distinguished for its high production values, complex harmonies and orchestrations, vocal layering, and introspective or ingenuous themes. Wilson is also known for his former high vocal range and lifelong struggles with mental illness.

Wilson's formative influences included

In 1964, Wilson had a

Heralding popular music's recognition as an art form, Wilson's accomplishments as a producer helped initiate an era of unprecedented creative autonomy for label-signed acts. His songs became defining works of the early 1960s zeitgeist and he is regarded as an important figure to many music genres and movements, including the California sound, art pop, psychedelia, chamber pop, progressive music, punk, outsider, and sunshine pop. Since the 1980s, his influence has extended to styles such as post-punk, indie rock, emo, dream pop, Shibuya-kei, and chillwave. He has received numerous industry awards, multiple hall of fame inductions, and frequent inclusion in critics' lists of the greatest musicians of all time.

1942–1961: Background and musical training

Childhood

Brian Douglas Wilson was born on June 20, 1942, at Centinela Hospital Medical Center in Inglewood, California, the first child of Audree Neva (née Korthof) and Murry Wilson, a machinist who later pursued songwriting part-time.[1][2] Wilson's two younger brothers, Dennis and Carl, were born in 1944 and 1946.[3] Shortly after Dennis' birth, the family moved from Inglewood to 3701 West 119th Street in nearby Hawthorne, California.[4][3] Wilson, along with his siblings, suffered psychological and sporadic physical maltreatment from their father.[5] His 2016 memoir characterizes his father as "violent" and "cruel"; however, it also suggests that certain narratives about the mistreatment had been overstated or unfounded.[6]

From an early age, Wilson exhibited an aptitude for

I got so into The Four Freshmen. I could identify with Bob Flanigan's high voice. He taught me how to sing high. I worked for a year on The Four Freshmen with my hi-fi set. I eventually learned every song they did.

Wilson sang with peers at school functions, as well as with family and friends at home, and guided his two brothers in learning harmony parts, which they would rehearse together. He also played piano obsessively after school, deconstructing the harmonies of

One of Wilson's first forays into songwriting, penned when he was nine, was a reinterpretation of the lyrics to

High school and college

In high school, Wilson played

For his Senior Problems course in October 1959, Wilson submitted an essay, "My Philosophy", in which he stated that his ambitions were to "make a name for myself [...] in music."

In September 1960, Wilson enrolled as a psychology major at El Camino College in Los Angeles, also pursuing music.[37] Disappointed by his teachers' disdain for pop music, he withdrew from college after about 18 months.[38] By his account, he crafted his first entirely original melody, "Surfer Girl", in 1961, inspired by a Dion and the Belmonts rendition of "When You Wish Upon a Star". However, his close high school friends disputed his claim, recalling earlier original compositions.[39]

Formation of the Beach Boys

I wasn't aware those early songs defined California so well until much later in my career. I certainly didn't set out to do it. I wasn't into surfing at all. My brother Dennis gave me all the jargon I needed to write the songs. He was the surfer and I was the songwriter.

The three Wilson brothers, Love, and Jardine debuted their first music group together, called "the Pendletones", in the autumn of 1961. At Dennis's suggestion, Brian and Love co-wrote the group's first song, "

Produced by Hite and Dorinda Morgan on Candix Records, "Surfin'" became a hit in Los Angeles and reached 75 on the national Billboard sales charts.[43] However, the group's name was changed by Candix Records to the Beach Boys.[44] Their major live debut was at the Ritchie Valens Memorial Dance on New Year's Eve, 1961. Just days before, Wilson had received an electric bass from his father, quickly learning to play with Jardine switching to rhythm guitar.[45]

When Candix Records faced financial difficulties and sold the Beach Boys' master recordings to another label, Murry ended their contract. As "Surfin'" faded from the charts, Wilson collaborated with local musician Gary Usher to produce demo recordings for new tracks, including "409" and "Surfin' Safari". Capitol Records were persuaded to release the demos as a single, achieving a double-sided national hit.[46]

1962–1966: Peak years

Brian Wilson is the Beach Boys. He is the band. We're his fucking messengers. He is all of it. Period. We're nothing. He's everything.

Early productions and freelancing

In 1962, Wilson and the Beach Boys signed a seven-year contract with Capitol Records under producer Nick Venet.[48][49] During sessions for their debut album, Surfin' Safari, Wilson negotiated with Capitol to record the band outside the label's basement studios, which he deemed ill-suited for his group.[50][nb 4] At Wilson's insistence, Capitol permitted the Beach Boys to fund their own external sessions while retaining all rights to the recordings.[50] He also secured production control over the album, though he was not credited for this role in the liner notes.[50][51]

Inspired by producer Phil Spector, whose work with the Teddy Bears he admired, Wilson sought to emulate Spector's career path.[52][53] Wilson reflected, "I've always felt I was a behind-the-scenes man, rather than an entertainer."[54] Collaborating with songwriter Gary Usher, he composed numerous songs patterned after the Teddy Bears' style and produced records for local talent, though without commercial breakthrough.[55] His first uncredited production outside the Beach Boys was Rachel and the Revolvers' "The Revo-Lution", co-written with Usher and released by Dot Records in September.[56] Interference from Wilson's father eventually led to the dissolution of his partnership with Usher.[57][58]

By mid-1962, Wilson was writing with disc jockey

From January to March 1963, Wilson produced the Beach Boys' second album,

Against Venet's wishes, Wilson collaborated with artists outside Capitol, including the

Around this time, Wilson began producing the Rovell Sisters, a girl group consisting of sisters Marilyn and Diane Rovell and their cousin Ginger Blake, whom he met at a Beach Boys concert the previous August.[74] Wilson pitched the group to Capitol as "the Honeys", a female counterpart to the Beach Boys. The company released several Honeys records as singles, though they sold poorly.[75] He grew close to the Rovell family and resided primarily at their home through 1963 and 1964.[76] The group's fourth single "He's a Doll", released in April 1964,[77] exemplified his attempts to become an entrepreneurial producer like Spector.[78]

Wilson was first officially credited as the Beach Boys' producer on their album Surfer Girl, recorded in June and July 1963 and released that September.[79] This LP reached number seven on the national charts, with similarly successful singles.[80] He also produced the car-themed album Little Deuce Coupe, released just three weeks after Surfer Girl.[81] Still resistant to touring, Jardine was his live substitute. By late 1963, Marks' departure necessitated Wilson's return to the touring lineup.[81][82] By the end of the year, Wilson had written, arranged, or produced 42 songs for other acts.[73][nb 5]

International success and Houston flight incident

Throughout 1964, Wilson toured internationally with the Beach Boys while writing and producing their albums Shut Down Volume 2 (March), All Summer Long (June), and The Beach Boys' Christmas Album (November).[84] Following a particularly stressful Australasian tour in early 1964, the group dismissed Murry as their manager.[85] Murry maintained occasional contact with Wilson, offering unsolicited advice on the group's business decisions.[86] Wilson also continued to solicit his father's opinions on musical matters.[87]

In February, Beatlemania swept the U.S., a development that deeply concerned Wilson, who felt the Beach Boys' supremacy had been threatened by the British Invasion.[88][89] Reflecting in 1966, he said, "The Beatles invasion shook me up a lot. [...] So we stepped on the gas a little bit."[77] The Beach Boys' May 1964 single "I Get Around", their first U.S. number-one hit, is identified by scholar James Perone as representing both a successful response to the British Invasion and the beginning of an unofficial rivalry between Wilson and the Beatles, principally Paul McCartney.[90] The B-side, "Don't Worry Baby", was cited by Wilson in a 1970 interview as "Probably the best record we've done".[91]

By late 1964, Wilson faced mounting psychological strain from career pressures.[92] He began distancing himself from the Beach Boys' surf-themed material, which had ceased following the All Summer Long track "Don't Back Down".[93] During the group's first major European tour, a reporter asked how he had felt about originating the surfing sound, to which he responded by saying he had aimed to "produce a sound that teens dig, and that can be applied to any theme."[94] Exhausted by his self-described "Mr Everything" role, he later expressed feeling mentally drained and unable to rest.[95] Adding to his concerns was the group's "business operations" and the quality of their records, which he believed suffered from this arrangement.[96]

On December 23, 1964, Wilson was to accompany his bandmates for a two-week U.S. tour, but during a flight from Los Angeles to Houston, he experienced a breakdown, sobbing uncontrollably due to stress over his recent marriage to Marilyn Rovell.[98][99] Jardine recalled, "None of us had ever witnessed something like that."[98] Wilson played the show in Houston later that day, but was replaced by session musician Glen Campbell for the rest of the tour.[100][nb 6] Wilson, speaking in 1966, described it as "the first of a series of three breakdowns".[96] When the group resumed recording their next album in January 1965, Wilson declared that he would be withdrawing from future tours.[101][102] Wilson attributed his decision partly to a "fucked up" jealousy of Spector and the Beatles.[103][nb 7]

Campbell continued substituting for Wilson on tour until February 1965, after which Wilson produced Campbell's solo single, "Guess I'm Dumb", as a gesture of appreciation. Columbia Records staff producer Bruce Johnston was subsequently hired as Wilson's permanent touring replacement.[107][nb 8]

Growing drug use and religious epiphany

With his bandmates frequently touring, Wilson grew socially distant from the Beach Boys.

[In 1965] I had what I consider to be a very religious experience. I took LSD, a full dose of LSD, and later, another time, I took a smaller dose. And I learned a lot of things, like patience, understanding. I can't teach you, or tell you what I learned from taking it.

Throughout 1965, Wilson's musical ambitions progressed significantly with the albums

After unsuccessful efforts to distance Wilson from Schwartz, Marilyn temporarily separated from him.

Pet Sounds and Smile

Wilson recalled that after relocating to his Beverly Hills home, he experienced an unexpected surge of creativity, working for hours to develop new musical ideas. He acknowledged heavy drug use, stating, "I was taking [...] a lot of pills, and it fouled me up for a while. It got me really introspective".[128] Over five months, he planned an album that would elevate his music to "a spiritual level".[128]

In December 1965, Wilson enlisted jingle writer Tony Asher as his lyricist for the Beach Boys' next album, Pet Sounds (May 1966).[129] He produced most of the album between January and April 1966 across multiple Hollywood studios, mainly employing his bandmates for singing vocal parts and session musicians for the backing tracks.[130] Reflecting on the album, Wilson highlighted the instrumental "Let's Go Away for Awhile" as his "most satisfying piece of music" at the time and "I Just Wasn't Made for These Times" as a partially autobiographical song "about a guy who was crying because he thought he was too advanced".[131][132] In a 1995 interview, he called "Caroline, No" "probably the best [song] I've ever written."[132]

The thing that I remember the most is that when Pet Sounds wasn't as quickly a hit or as huge or an immediate success, it really destroyed Brian. He just lost a lot of faith in people and music.

The album's lead single, "Caroline, No", released in March 1966, became Wilson's first solo credit,[134] sparking speculation about his potential departure from the Beach Boys.[135] Wilson later said, "I explained to [the group], 'It's OK. It is only a temporary rift […] I wanted to step out a little bit.'"[134] The single peaked at number 32, while Pet Sounds reached number 10.[136] Wilson was "mortified" that his artistic growth had failed to translate into a number-one album.[137] Marilyn stated, "When it wasn't received by the public the way he thought it would be received, it made him hold back. ... but he didn't stop. He couldn't stop. He needed to create more."[133]

Wilson met Derek Taylor, the Beatles' former press officer, who became the Beach Boys' publicist in 1966. At Wilson's request, Taylor launched a media campaign to elevate his public image, promoting him as a "genius".[138][139] Taylor's reputation and outreach bolstered the album's critical success in the UK.[138][139][140] However, Wilson later expressed resentment toward the "genius" label, which he felt heightened unrealistic expectations for his work.[141][142] Bandmates including Mike Love and Carl Wilson also grew frustrated as media coverage increasingly centered on Wilson, overshadowing the group's collaborative efforts.[143]

Through late 1966, Wilson worked extensively on the Beach Boys' single "

1967–1973: Decline

Home studio transition

Smile was never finished, due in large part to Wilson's worsening mental condition and exhaustion.[145] Associates often cite late 1966 as a turning point, coinciding with erratic behavior during sessions for the track "Fire" (or "Mrs. O'Leary's Cow").[150] In April 1967, Wilson and his wife relocated to a newly purchased mansion on 10452 Bellagio Road in Bel Air.[149][151][nb 10] There, Wilson began constructing a personal home studio.[149] By this time, most of his recent associates had departed or been excluded from his life.[153]

When I was younger, I was a real competitor. Then as I got older, I said, "Is it worth the bullshit? To compete like that?" And I said, "Nah." For a while there, I just said, "Hey, I'm going to coast. I'm going to make real nice music. Nothing competitive."

In May, Derek Taylor announced that Smile had been "scrapped".[155] Wilson explained in a 1968 interview, "We pulled out [...] because I was about ready to die. I was trying so hard. So, all of a sudden I decided not to try any more."[156] That July, the Beach Boys released "Heroes and Villains" as a single; its mixed critical and commercial reception further strained Wilson's morale, with biographers citing it as a factor in his professional and psychological decline.[157][158] He later acknowledged that upholding his industry reputation "was a really big thing for me" and that he had grown weary of demands to produce "great orchestral stuff all the time".[159]

Beginning with Smiley Smile (September 1967), the band shifted recording operations to Wilson's studio, where they worked intermittently until 1972. The album marked the first time production was credited to the group collectively instead of Wilson alone.[160][161] Producer Terry Melcher attributed this change to Wilson's reluctance to risk individual scrutiny, saying he no longer wanted to "put his stamp on records".[162] In August 1967, Wilson briefly rejoined the band for two live performances in Honolulu, recorded for an unfinished live album titled Lei'd in Hawaii.[163]

During sessions for Wild Honey (December 1967), Wilson encouraged his brother Carl to contribute more to the record-making process.[141] He also began producing tracks for Danny Hutton's group Redwood, recording three songs including "Time to Get Alone" and "Darlin'", but the project was halted by Carl and Mike Love, who urged Brian to prioritize Beach Boys commitments.[164] The band's June 1968 album Friends was recorded during a period of emotional recovery for Wilson.[165] While the album featured increased contributions from other members, Wilson remained central, even on tracks he did not write.[166] He later described Friends as his second "solo album" (after Pet Sounds)[167] and his favorite Beach Boys album.[168][165]

Reduced activity and "Bedroom Tapes"

For the remainder of 1968, Wilson's songwriting output declined substantially, as did his emotional state, leading him to self-medicate with overconsumption of food, alcohol, and drugs.[169] As the Beach Boys faced impending financial collapse, he began to supplement his regular amphetamines and marijuana with cocaine,[170] which Hutton had introduced to him.[171] Hutton later stated that Wilson expressed suicidal ideation during this period, describing it as the onset of Wilson's "real decline".[170]

In mid-1968, Wilson was admitted to a psychiatric hospital, possibly voluntarily.[172] His hospitalization was kept private, and his bandmates proceeded with recording sessions for 20/20 (February 1969).[172] Once discharged later in the year, Wilson rarely finished any tracks for the band, leaving much of his subsequent output for Carl to complete.[173] Journalist Nik Cohn wrote in 1968 that Wilson had become the subject of rumors describing him as "increasingly withdrawn", "brooding", and "hermitic" [sic], with occasional sightings of him "in the back of some limousine, cruising around Hollywood, bleary and unshaven, huddled way tight into himself."[174]

Brian went through a period where he would write songs and play them for a few people in his living room, and that's the last you'd hear of them. He would disappear back up to his bedroom and the song with him.

Wilson typically stayed secluded upstairs while the group recorded below, joining sessions only to suggest revisions to music he had overheard.[176] He occasionally emerged from his bedroom to preview new songs for the group. Melcher likened these appearances to Aesop delivering a new fable.[175][173] Journalist Brian Chidester later coined the term "Bedroom Tapes" to refer to Wilson's unreleased output between 1968 and 1975, most of which remains unheard publicly.[173]

According to Mike Love, Wilson had "lost interest in the mechanical aspect" of recording, deferring technical work to Carl.[177] Band engineer Stephen Desper said that Brian remained "indirectly involved" with the group's productions through Carl[178] and that Brian's reduced contributions stemmed from "limited hours in the day", as well as his aversion to confrontation: "Brian [...] doesn't like to hurt anyone's feelings, so if someone's working on something else, he wasn't going to jump in there and say, 'Look, this is my production and my house, so get outta here!'"[179] Conversely, Dennis stated that Brian had "no involvement at all" with the band beginning with the 20/20 sessions, forcing them to salvage and assemble fragments of his earlier work.[180][nb 11] Marilyn recalled that her husband withdrew because of perceived resentment from the group: "It was like, 'OK, you assholes, you think you can do as good as me or whatever—go ahead—you do it. You think it's so easy? You do it.'"[154]

Sea of Tunes sale and Reprise signing

Early in 1969, the Beach Boys commenced recording Sunflower (August 1970).[181] Wilson contributed numerous songs, though most were excluded from the final track selection.[179] He co-wrote and produced the single "Break Away" with his father in early 1969, after which he largely withdrew from studio work until August.[182] The group faced difficulties securing a new record deal, attributed by Gaines to Wilson's diminished standing in the industry.[183] In May 1969, Wilson disclosed the band's near-bankruptcy to reporters, which derailed negotiations with Deutsche Grammophon and nearly jeopardized their upcoming European tour.[184][185] That July, he opened a short-lived health food store, the Radiant Radish, with cousin Steve Korthof and associate Arny Geller.[186]

In August, the Beach Boys' publishing company, Sea of Tunes, sold their song catalog to Irving Almo Music for $700,000 ($6 million in 2024).[187] Wilson signed the consent form under pressure from his father.[188] Marilyn later stated that the sale emotionally devastated him: "It killed him. Killed him. I don't think he talked for days. [...] Brian took it as Murry not believing in him anymore."[189] During this period, Wilson reportedly engaged in self-destructive behavior, including an attempt to drive off a cliff and a demand to be buried in a backyard grave he had dug.[190][nb 12] He channeled his despondence into writing "'Til I Die", later calling the song a summation of "everything I had to say at the time."[192]

Later in 1969, Wilson produced poet

Spring and Mount Vernon and Fairway

Wilson's disappointment over the poor commercial reception of Sunflower

From late 1971 to early 1972, Wilson and musician David Sandler collaborated on

During the summer of 1972, Wilson joined his bandmates when they temporarily relocated to Holland after persistent persuasion.[210] Residing in a Dutch house known as "Flowers" and repeatedly listening to Randy Newman's album Sail Away, he was inspired to write a fairy tale, Mount Vernon and Fairway, drawing on memories of listening to the radio at Mike Love's family home in his youth.[211] The group declined to include the fairy tale on their next album, Holland (January 1973), and instead released it as a bonus EP packaged with the album.[212] That April, Wilson briefly joined his bandmates onstage during an encore at the Hollywood Palladium.[213]

1973–1975: Recluse period

I was taking some drugs and I experimented myself right out of action. [...] I'd sometimes go and record. But basically I just stayed in my bedroom. I was under the sheets and I watched television.

After his father's death in June 1973, Wilson secluded himself in the chauffeur's quarters of his home, where he spent his time sleeping, abusing drugs and alcohol, overeating, and exhibiting self-destructive behavior.[215] He rarely ventured outside wearing anything but pajamas and later said that his father's death "had a lot to do with my retreating".[216] Wilson's family were eventually forced to take control of his financial affairs due to his irresponsible drug expenditures.[217][218][nb 16] This led Wilson to occasionally wander the city, begging for rides, drugs, and alcohol.[218]

According to Wilson, from 1974 to 1975, his output was confined to minimal, fragmentary recordings, due to a diminished capacity for sustained concentration.

Many reported anecdotes involving Wilson in the early 1970s, though frequently of questionable veracity, attained a legendary status.

The Beach Boys' greatest hits compilation Endless Summer was a surprise success, becoming the band's second number-one U.S. album in October 1974. To take advantage of their sudden resurgence in popularity, Wilson agreed to join his bandmates in Colorado for the recording of a new album at James William Guercio's Caribou Ranch studio.[231] The group completed a few tracks, including "Child of Winter (Christmas Song)", but ultimately abandoned the project.[232] Released as a single at the end of December 1974, "Child of Winter" was their first record that displayed the credit "Produced by Brian Wilson" since 1966.[233]

Early in 1975, while still under contract with Warner Bros., Wilson signed a short-lived sideline production deal with Bruce Johnston and Terry Melcher's Equinox Records. Together, they founded the loose-knit supergroup known as California Music, which also involved Gary Usher, Curt Boettcher, and other Los Angeles musicians.[215] Along with his guest appearances on Johnny Rivers' rendition of "Help Me, Rhonda" and Jackie DeShannon's "Boat to Sail", Wilson's production of California Music's single "Why Do Fools Fall in Love" represents his only "serious" work throughout this period.[234]

1975–1982: "Brian's Back!"

15 Big Ones, Love You, and Adult/Child

Wilson's increased consumption of food, cigarettes, alcohol, and other drugs—including

Under Landy's care, Wilson stabilized and became more socially engaged, renewing his productivity.

Beginning on July 2, 1976, Wilson resumed regular performances with the band for the first time since 1964, singing and alternating between bass guitar and piano.

That's when it all happened for me. That's where my heart lies. Love You, Jesus, that's the best album we ever made.

From October 1976 to January 1977, Wilson produced a collection of recordings largely on his own while his bandmates pursued other creative and personal endeavors.[253] Released in April 1977, The Beach Boys Love You was the band's first album to feature Wilson as the primary composer since Wild Honey in 1967.[254] Originally titled Brian Loves You,[255] the album showcased Wilson playing nearly every instrument.[256] Band engineer Earle Mankey described it as Wilson's effort to create a "serious, autobiographical" work.[257] In a 1998 interview, Wilson listed 15 Big Ones and Love You as his two favorite Beach Boys albums.[252]

At the end of 1976, Wilson's family and management dismissed Landy after he raised his monthly fee to $20,000 ($111,000 in 2024).[258] Shortly afterward, Wilson told a journalist he considered the treatment successful.[259] Landy's role was immediately assumed by his cousins, Steve Korthof and Stan Love, and professional model Rocky Pamplin—a college friend of Stan.[260] Under their supervision, Wilson maintained a healthy, drug-free lifestyle for several months.[261]

In early 1977, Wilson produced Adult/Child, intended as the follow-up to Love You, but some bandmates voiced concerns about the work, leading to its non-release.[262] In March, the Beach Boys signed with CBS Records, whose contract required Wilson to compose most of the material for all subsequent albums. According to Gaines, Wilson was distraught at the prospect.[263] In reference to the sessions for M.I.U. Album (October 1978), Wilson described experiencing a "mental blank-out".[264] He was credited as the album's "executive producer".[265] Stan noted that Wilson was "depressed"[266] and reluctant to write with Mike, though Mike persisted.[267] Around this time, Wilson attempted to produce an album for Pamplin that would have featured the Honeys as backing vocalists.[268]

Hospitalizations and "cocaine sessions"

After a disastrous Australian tour in 1978, Wilson regressed and began secretly acquiring cocaine and barbiturates.

With his marriage unraveling, Wilson left his mansion in Beverly Hills for a modest home on Sunset Boulevard, where his alcoholism worsened.[275] After attacking his doctor, he was institutionalized at Brotzman Memorial Hospital[276][277]—initially admitted in November 1978 for three months, discharged for one month, then readmitted.[278] In January 1979, while hospitalized, his caregivers Stan Love and Rocky Pamplin were dismissed.[279] Wilson was released in March.[280] He rented a house in Santa Monica and was cared for by a "round-the-clock" psychiatric nursing team.[281] Later, he purchased a home in Pacific Palisades.[282] Although his bandmates urged him to produce their next album, Keepin' the Summer Alive (March 1980), he was unable or unwilling to do so.[283][284]

Wilson continued his overeating and drug habits.

In early 1981, Pamplin and Stan Love were convicted of assaulting Dennis after learning he had been providing Wilson with drugs.[289] In early 1982, Wilson signed a trust document granting Carl control of his finances and voting power in the band's corporate structure, and he was involuntarily admitted for a three-day stay at St. John's Hospital in Santa Monica.[290] By the end of the year, his weight exceeded 340 pounds (150 kg).[291]

1982–1991: Second Landy intervention

Recovery and the Wilson Project

In 1982, after overdosing on alcohol, cocaine, and other drugs,[292] Wilson's family and management staged an elaborate ruse to persuade him to reenter Landy's program.[293][294] On November 5, the group falsely informed Wilson that he was destitute and no longer a Beach Boy, insisting he reenlist Landy as his caretaker to continue receiving his touring income.[293] Landy agreed to resume treatment only if granted complete control over Wilson's affairs and promised rehabilitation within two years.[295]

Wilson acquiesced and was taken to Hawaii, where he was isolated from friends and family and placed on a strict diet and health regimen.[296][297] Combined with counseling sessions that retaught him basic social etiquette, the treatment restored his physical health.[298] By March 1983, he had returned to Los Angeles and was moved, under Landy's direction, to a Malibu home where he lived with several of Landy's aides and was cut off from many of his own friends and family.[299]

Between 1983 and 1986, Landy charged approximately $430,000 annually ($1.36 million in 2024). When he requested additional funds, Carl Wilson was obliged to allocate a quarter of Brian's publishing royalties.[292] Landy gradually assumed the role of Wilson's creative and financial partner, eventually representing him at Brother Records, Inc. corporate meetings.[300][301] Landy was accused of creating a Svengali-like environment by controlling every aspect of Wilson's life—including his musical direction.[302] Wilson countered these claims, stating, "People say that Dr. Landy runs my life, but the truth is, I'm in charge."[303] He later claimed that in mid-1985 he attempted suicide by swimming as far out to sea as possible before one of Landy's aides retrieved him.[304]

As Wilson's recovery consolidated, he participated in recording

Brian Wilson, Sweet Insanity, first memoir, and conservatorship

Wilson occasionally rejoined his bandmates on stage and performed his first ever solo gigs at several charity concerts around Los Angeles.[309] In January 1987, he accepted a solo contract from Sire Records president Seymour Stein, mandated co-production by multi-instrumentalist Andy Paley to keep Wilson focused.[304][307] In return, Landy was allowed to serve as executive producer.[304] Other producers, including Russ Titelman and Lenny Waronker, soon joined the project, and conflicts with Landy emerged.[310]

Released in July 1988, Brian Wilson received favorable reviews and moderate sales, peaking at number 52 in the U.S.[307][311] The album featured "Rio Grande", an eight-minute Western suite reminiscent of songs from Smile.[312] Its release was largely overshadowed by the controversy surrounding Landy and the success of the Beach Boys' "Kokomo", their first number-one hit since "Good Vibrations" and the first without Wilson's involvement.[313] By 1990, Wilson was estranged from the Beach Boys, with his bandmates scheduling recording sessions without him and twice rejecting his offers to produce an album, according to Brother Records president Elliot Lott.[314]

In 1989, Wilson and Landy formed the company Brains and Genius. By then, Landy was no longer legally recognized as Wilson's therapist and had surrendered his California psychology license.[315] Together, they worked on Wilson's second solo album, Sweet Insanity, with Landy co-writing nearly all the material.[316] Sire rejected the album due to Landy's lyrics and the inclusion of Wilson's rap song "Smart Girls".[307] In May 1989, Wilson recorded "Daddy's Little Girl" for the film She's Out of Control, and in June, he was among the featured guests on the charity single "The Spirit of the Forest".[307]

In October 1991, Wilson published his first memoir, Wouldn't It Be Nice: My Own Story.[317] Biographer Peter Ames Carlin noted that the book plagiarized excerpts from earlier biographies and ranged from harsh criticisms of his bandmates to passages resembling legal depositions.[317] The memoir prompted defamation lawsuits from Mike Love, Al Jardine, Carl Wilson, and his mother, Audree Wilson.[318][319] After a conservatorship suit filed by his family in May 1991, Wilson and Landy's partnership was dissolved in December, followed by a restraining order.[318]

1992–2019: Career resurgence and touring

Lawsuits, documentary, and collaborative albums

Throughout the 1990s, Wilson was embroiled in numerous lawsuits.

Wilson's productivity had increased significantly after his disassociation from Landy.[323] He and Andy Paley composed and recorded a substantial body of material intended for a proposed Beach Boys album throughout the early to mid-1990s.[324] Concurrently, Wilson collaborated with musician Don Was on the documentary Brian Wilson: I Just Wasn't Made for These Times (1995), whose soundtrack—comprising rerecorded Beach Boys songs—was released in August as his second solo album.[325][326]

In 1993, Wilson agreed to record an album of songs by Van Dyke Parks,[327] which was credited to the duo and released as Orange Crate Art in October 1995.[326][328] In the late 1990s, Wilson and Tony Asher rekindled their writing partnership,[329] and one of their songs, "Everything I Need", appeared on The Wilsons (1997)—a project by his daughters Carnie and Wendy that included select contributions from Wilson.[329]

Imagination and first solo tours

Although some recordings with the Beach Boys were completed, the Wilson–Paley project was eventually abandoned.[331] Instead, Wilson co-produced the band's 1996 album Stars and Stripes Vol. 1 with Joe Thomas, owner of River North Records.[332] In 1997, Wilson relocated to St. Charles, Illinois, to work on a solo project with Thomas.[333] His third solo album, Imagination (June 1998)—which he described as "really a Brian Wilson/Joe Thomas album"—peaked at number 88 in the U.S. and received criticism for its homogenized radio pop sound.[334] Shortly before the album's release, Wilson lost his brother Carl and their mother Audree.[335]

Some reports from this period suggested that Wilson was exploited by those close to him, including Melinda.[336] His daughter Carnie nicknamed Ledbetter "Melandy",[330] while family friend Ginger Blake described Wilson as "complacent and basically surrendered".[337] Mike Love stated his willingness to reunite the Beach Boys with Wilson but remarked that "Brian usually has someone in his life who tells him what to do. And now that person kinda wants to keep him away from us. I don't know why. You'd have to ask her, I guess."[336] When asked if he still considered himself a Beach Boy, Wilson responded, "No. Maybe a little bit."[336] Debate persisted among fans over whether Wilson fully consented to his semi-regular touring schedule through the 2010s.[338][nb 21]

From March to July 1999, Wilson embarked on his first solo tour, playing about a dozen dates in the U.S. and Japan.[340] His supporting band included former Beach Boys touring musician Jeff Foskett (guitar), Wondermints members Darian Sahanaja (keyboards), Nick Walusko (guitar), Mike D'Amico (percussion, drums), and Probyn Gregory (guitar, horns); along with Chicago-based session musicians Scott Bennett (various), Paul Mertens (woodwinds), Bob Lizik (bass), Todd Sucherman (drums), and Taylor Mills (backing vocals).[341][342] He toured the U.S. again in October.[343] In 2000, he stated, "I feel much more comfortable on stage now. I have a good band behind me. It's a much better band than the Beach Boys were."[344]

In August 1999, Wilson filed suit against Thomas, seeking damages and a declaration that he could work on his next album without Thomas's involvement.[345] Thomas counter-sued, alleging that Wilson's wife had "schemed against and manipulated" him and Wilson; the case was settled out of court.[346]

Live albums and Brian Wilson Presents Smile

Early in 2000, Wilson released his first live album, Live at the Roxy Theatre.[347] Later that year, he embarked on U.S. tour dates featuring the first full live performances of Pet Sounds, with Wilson backed by a 55-piece orchestra. Van Dyke Parks was commissioned to write an overture arrangement of Wilson's songs.[348] Although critics praised the tour, it was poorly attended and resulted in hundreds of thousands of dollars in losses.[347] In March 2001, Wilson attended a tribute show held in his honor at Radio City Music Hall in New York, where he performed "Heroes and Villains" publicly for the first time in decades.[349][350]

The Pet Sounds tour was followed by one in Europe in 2002, with a sold-out four-night residency at the Royal Festival Hall in London.[351] Recordings from these concerts were issued as the live album Brian Wilson Presents Pet Sounds Live (June 2002).[352] Over the next year, Wilson continued sporadic recording sessions for his fourth solo album, Gettin' In over My Head.[353] Released in June 2004, the record featured guest appearances from Parks, Paul McCartney, Eric Clapton, and Elton John.[354] Some of the songs were leftovers from Wilson's collaborations with Paley and Thomas.[355]

To the surprise of his associates, Wilson agreed to follow the Pet Sounds tours with concert dates featuring songs from the unfinished Smile album.[356] Sahanaja assisted with sequencing and Parks contributed additional lyrics.[357] Brian Wilson Presents Smile (BWPS) premiered at the Royal Festival Hall in London in February 2004[358] and its positive reception led to a subsequent studio album adaptation.[359] Released in September, BWPS debuted at number 13 on the Billboard 200, the highest chart position for any album by the Beach Boys or Wilson since 1976's 15 Big Ones[360] and the highest ever debut for a Beach Boys-related album.[361] It was later certified platinum.[362]

In support of BWPS, Wilson embarked on a tour covering the U.S., Europe, and Japan.[363] Sahanaja told Australian Musician, "In six years of touring this is the happiest we've ever seen Brian".[364] In July 2005, Wilson performed at the Live 8 in Berlin, an event watched by about three million viewers on television.[365] In September, he organized a charity drive for Hurricane Katrina victims, raising over $250,000.[366] In November, Mike Love filed a lawsuit alleging that Wilson misappropriated his songs, likeness, the Beach Boys trademark, and the Smile album in connection with BWPS.[367][47] The suit was dismissed.[368]

Covers albums, That Lucky Old Sun, and Beach Boys reunion

In October 2005, Arista Records released Wilson's album What I Really Want for Christmas, featuring two new originals by Wilson.[369] To celebrate the 40th anniversary of Pet Sounds, he toured the album briefly in November 2006 with Al Jardine.[370][371] In 2007, the Southbank Centre in London commissioned Wilson to create a new song cycle in the style of Smile. Collaborating with Scott Bennett, Wilson reconfigured a collection of recently written songs into That Lucky Old Sun, a semi-autobiographical conceptual piece about California.[372] A studio-recorded version of the work was released as his seventh solo album in September 2008 and received generally favorable reviews.[373][nb 22]

In 2009, Wilson was approached by Walt Disney Records to record a Disney songs album, agreeing only if he could also record an album of George Gershwin songs.[375] The Gershwin project, Brian Wilson Reimagines Gershwin, was released in August 2010, reaching number 26 on the Billboard 200 and topping its Jazz Albums chart. Wilson then toured, performing the album in its entirety.[376] In October 2011, he released In the Key of Disney, which peaked at number 83 in the U.S. This release was soon overshadowed by The Smile Sessions, issued one week later.[377]

In mid-2011, he reunited with Mike Love, Al Jardine, David Marks, and Bruce Johnston to re-record "Do It Again" in secret for a potential 50th anniversary album.[378] Rumors soon circulated in the music press about a world tour by the group. In a September report, Wilson said he was not participating in the tour with his bandmates, remarking, "I don't really like working with the guys, but it all depends on how we feel and how much money's involved. Money's not the only reason I made records, but it does hold a place in our lives."[379]

Ultimately, Wilson agreed to the tour—which lasted until September 2012—and to record the album That's Why God Made the Radio, released in June 2012.[380] By that time, Wilson had renewed his creative partnership with Joe Thomas. Although Wilson was listed as the album's producer, Thomas was credited with "recording" and Love with "executive producer".[381]

No Pier Pressure and Pet Sounds 50th Anniversary World Tour

In June 2013, Wilson's website announced that he was recording and self-producing new material with Don Was, Al Jardine, David Marks, Blondie Chaplin, and Jeff Beck.[382] It stated that the material might be split into three albums: one of new pop songs, another of mostly instrumental tracks with Beck, and another of interwoven tracks dubbed "the suite" which initially began form as the closing four tracks of That's Why God Made the Radio.[383] In January 2014, Wilson declared in an interview that the Beck collaborations would not be released.[384][385]

In September 2014, Wilson attended the premiere of Bill Pohlad's biopic Love & Mercy at the Toronto International Film Festival.[386] He had contributed "One Kind of Love" to the film, which later received a Golden Globe nomination for Best Original Song.[387] In October, BBC released a re-recorded version of "God Only Knows" —featuring Wilson, Brian May, Elton John, Jake Bugg, Stevie Wonder, Lorde, and others—to commemorate the launch of BBC Music.[388] A week later, he was featured as a guest vocalist on Emile Haynie's single "Falling Apart".[389] His cover of Paul McCartney's "Wanderlust" was included on the tribute album The Art of McCartney in November.[390]

Released in April 2015,

In March 2016, Wilson and Al Jardine began the Pet Sounds 50th Anniversary World Tour, billed as his final performances of the album.[395] In October, his second memoir, I Am Brian Wilson, written by journalist Ben Greenman after several months of interviews, was published.[396][nb 23] Asked about negative remarks in Wilson's book, Love refuted that his printed statements were spoken and argued that Wilson was "not in charge of his life, like I am mine", adding that he preferred to avoid pressuring Wilson "because I know he has a lot of issues."[399] In the late 2010s, Wilson remarked to a journalist that he had not "had a friend to talk to in three years."[400]

In a 2016 Rolling Stone interview, Wilson responded to a retirement question by stating he would rather continue touring than sit idle.[401] In 2019, Wilson embarked on a co-headlining tour with the Zombies, performing selections from Friends and Surf's Up.[402]

2020s: At My Piano, UMPG sale, and dementia

Around this time, Wilson had two back surgeries that left him reliant on a walker.[403] In 2019, he postponed some concert dates due to worsening mental health.[404] The next month, his social media declared that he had recovered and would resume touring.[405] Pausing his tours due to the COVID-19 pandemic,[406] he resumed touring in August 2021.[407] In November, two releases followed: At My Piano, featuring new instrumental piano recordings of his songs,[408] and the soundtrack to Brian Wilson: Long Promised Road, which includes both new and previously unreleased recordings.[409]

At the end of 2021, Wilson sold his publishing rights to Universal Music Publishing Group for $50 million. Wilson was paid almost $32 million for his songwriter share plus $19 million for his reversion rights (his ability to reclaim his song rights within a time period after signing them away under the Copyright Act of 1976).[410] In 2022, his ex-wife Marilyn, who had been awarded half of his songwriting royalties, sued Wilson for $6.7 million.[410]

On July 26, 2022, Wilson played his final concert as part of a joint tour with Chicago at the Pine Knob Music Theatre in Clarkston, Michigan, where he was reported to have "sat rigid and expressionless" throughout the performance.[411] Days later, he cancelled his remaining tour dates for that year, with his management citing "unforeseen health reasons".[412] During a January 2023 appearance on a Beach Boys fan podcast, Wilson's daughter Carnie reported that her father was "probably not going to tour anymore, which is heartbreaking".[413]

On January 30, 2024, Melinda Ledbetter died at their home.[414] The following month, it was announced that Wilson had dementia and entered into another conservatorship, which began in May 2024.[415][416]

Cows in the Pasture, the unfinished album Wilson had produced for Fred Vail in 1970, is to be released in 2025, accompanied by a docuseries about Vail and the album's making.[417]

Musical influences

Early influences

Wilson's chordal vocabulary derived primarily from rock and roll, doo-wop, and vocal jazz.[418] At age two, he heard Glenn Miller's 1943 rendition of Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue, an experience that left a lasting emotional impact[419][420]—later saying, "It sort of became a general life theme".[421] As a child, his favorite artists included Roy Rogers, Carl Perkins, Bill Haley, Elvis Presley, Henry Mancini, and Rosemary Clooney.[13] He recalled Haley's "Rock Around the Clock" (1954) as the first music he felt compelled to learn and sing.[224] His education in music composition and jazz harmony largely came from deconstructing the vocal harmonies of the Four Freshmen, whose repertoire included works by Gershwin, Jerome Kern, and Cole Porter.[422][nb 24]

Wilson credited his mother with introducing him to the Four Freshmen,

Inquired for his music tastes in 1961, Wilson replied, "top 10".[432] Particular favorites included Chuck Berry, the Coasters, and the Everly Brothers.[433] He particularly admired Berry's "rhythm and lyrical thoughts".[434] Carl said that he and his brother "were total Chuck Berry freaks" and together sang Coasters songs with Four Freshmen-style arrangements before the Beach Boys formed.[435]

Wilson disliked surf music. In the estimation of biographer Timothy White, he instead sought a "new plateau midway between Gershwin and the best Four Freshmen material" when forming his band.[436] Gershwin's influence became more pronounced later in his career, particularl after the 1970s when he dedicated himself to learning the violin parts from Rhapsody in Blue.[437] In 1994, he recorded a choral version of the piece with Van Dyke Parks.[438]

Spector and Bacharach

Phil Spector's influence on Wilson is widely acknowledged.[439][440] In 1966, he referred to Spector as "the single most influential producer",[441] and in 2000, "probably the biggest influence of all", noting, "Anybody with a good ear can hear that I was influenced by Spector."[442] He particularly admired his method of treating "the song as one giant instrument", valuing the enormous, spacious sound, with "the best drums I ever heard".[443] Upon hearing the Ronettes' 1963 hit "Be My Baby" on his car radio, he immediately pulled over and declared it the greatest record he had ever heard.[444][nb 26] Record producer Lou Adler personally introduced them only a few days later.[447][448]

Contrary to many accounts,[449] Spector's engineer, Larry Levine, recalled that Spector held Wilson in high regard and was openly effusive in his praise.[450] Levine said that the two producers "had a good rapport", with Wilson often attending Spector's recording sessions and consulting him about his production methods.[451][nb 27] After Spector's "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" (1964) became a hit for the Righteous Brothers, Wilson called co-writers Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil to laud the record as the greatest ever and expressed his desire to work with them in the future.[453] He submitted "Don't Worry Baby" and "Don't Hurt My Little Sister", both written with the Ronettes in mind, but Spector declined.[454]

Asked for songs that he wished he had written, Wilson listed three: "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'", "Be My Baby", and

Others

Wilson's other significant musical influences include

The Beatles inspired me. They didn't influence me.

It is often reported that the Beach Boys and the Beatles influenced each other,[473] although Wilson rejected the notion.[472][nb 32] He acknowledged that he had felt threatened by the Beatles' success[103] and that this awareness drove him to concentrate his efforts on trying to outdo them in the studio.[476] He praised Paul McCartney's stylistic versatility and commended his bass playing as "technically fantastic".[477]

In 1976, Wilson commented that he felt contemporary popular music had lacked the artistic integrity it once had,[167] with Queen's "Bohemian Rhapsody" (1975) being one exception.[478] In a 1988 interview, he named the 1982 compilation Stevie Wonder's Original Musiquarium I and Paul Simon's 1986 release Graceland among his ten favorite albums of all time.[479] In 2007, he cited Billy Joel as his favorite pianist.[480] By 2015, Wilson maintained that he does not listen to modern music, only "oldies but goodies".[481][482]

Artistry

Compositional style

Wilson's writing process, as he described in 1966, started with finding a basic chord pattern and rhythm that he termed "feels", or "brief note sequences, fragments of ideas". He explained, "once they're out of my head and into the open air, I can see them and touch them firmly."[483][484] He wrote later that he aspired to write songs that appear "simple, no matter how complex it really is."[485]

Common devices in Wilson's musical structures include jazz chords, such as sevenths and ninths.[486] Wilson attributed his use of minor seventh chords to his affinity for the music of Bacharach.[471] Chord inversions, particularly those featuring a tonic with a fifth in the bass, are also prevalent in his work,[487] again influenced by Bacharach.[434] The flattened subtonic, which is common in the music of the Four Freshmen and popular music in general, is the nondiatonic chord that appears the most in Wilson's compositions.[488] Sudden breaks into a cappella segments, again borrowed from the Four Freshmen, are another feature of his music, having been employed in "Salt Lake City" (1965) and "Sloop John B" (1966).[489]

Many of Wilson's compositions are marked by destabilized tonal centers.[490] He frequently uses key changes within verses and choruses, including "truck driver's modulations", to create dynamic shifts.[491] Tertian movement is another recurring technique.[492]

Wilson's

Some of Wilson's songs incorporate a I – IV – I – V pattern, a formula derived from "Da Doo Ron Ron",[495] as well as a circle of fifths sequence that begins with the mediant (iii), inspired by "Be My Baby".[496] He frequently uses stepwise-falling melodic lines,[497] stepwise diatonic rises,[498] and whole-step root movements.[499] Numerous songs alternate between supertonic and dominant chords or tonic and flattened subtonic chords, the latter featuring in the verses of "Guess I'm Dumb" and the intro to "California Girls".[500]

Lyrics

I don't carry a notebook or use a tape player. I like to tell a story in the songs with as few words as possible. I sort of tend to write what I've been through and look inside myself. Some of the songs are messages.

Wilson generally collaborated with another lyricist,

Although the Beach Boys became known for surfing imagery, his compositions with collaborators outside the band typically avoided this subject matter.[509] Unlike his contemporaries, social issues were never referenced in his lyrics.[502][nb 37] In his 2008 book Dark Mirror: The Pathology of the Singer-Songwriter, Donald Brackett identifies Wilson as "the Carl Sandburg and Robert Frost of popular music—deceptively simple, colloquial in phrasing, with a spare and evocative lyrical style embedded in the culture that created it."[511] Brackett opined that Wilson expressed "intense fragility" and "emotional vulnerability" to degrees that few other singer-songwriters had.[512]

Studios and musicians

Wilson said, "I was unable to really think as a producer up until the time where I really got familiar with Phil Spector's work. That was when I started to design the experience to be a record rather than just a song."[513] He frequently attended Spector's recording sessions, observing his arranging and recording techniques, and adopted Spector's choice of studios and session musicians, later known as the Wrecking Crew.[445][nb 38] Wilson established approximately one-third of a song's final arrangement during the writing process, with the remainder developed in the studio.[515][nb 39]

Rather than using Gold Star Studios, Spector's favored facility, Wilson chose Studio 3 at Western for its privacy and the presence of staff engineer Chuck Britz,[517] who served as Wilson's principal engineer from 1962 to 1967.[518][nb 40] While Britz typically handled technical tasks like level mixing and microphone placement,[436] Wilson made extensive adjustments to the setup,[520] usurping standard studio protocols of the era that limited console use to assigned engineers.[521] Once Britz prepared an initial configuration, Wilson took control of the console, directing session musicians from the booth using an intercom or non-verbal cues alongside chord charts.[522] Britz recalled that Wilson would work with the players until he achieved the desired sound, a process that frequently lasted for hours.[523]

Wilson first used the Wrecking Crew for productions with the Honeys in March 1963,[524] and two months later, during sessions for Surfer Girl, he began gradually integrating these musicians into Beach Boys records.[525][526][nb 41] Until 1965, the band members typically performed the instrumentation,[530][527] but as Wilson's sessions came to necessitate 11 or more different players, his reliance on the Wrecking Crew increased.[474] In 1966 and 1967, he almost exclusively used these musicians for the backing tracks,[527][530] although their involvement diminished considerably after 1967.[527]

His musicians, many trained in

Production style

Wilson's best-known productions typically employed instruments such as saxophones and

His first use of a string section was on "The Surfer Moon" in mid-1963.

Starting in 1964, Wilson performed

According to Wilson, after his first nervous breakdown in 1964, he had endeavored to "take the things I learned from Phil Spector" and maximize his instrumental palette.

Singing

Wilson's vocal style was shaped by studying the Four Freshmen, from whom he developed a versatile head voice that allowed him to hit high notes without resorting to falsetto, although he did use falsetto on some Beach Boys tracks.[428] He recalled that he "learned how to sing falsetto" through listening to Four Freshmen renditions.[548] Rosemary Clooney also influenced his singing; by mimicking her phrasing on recordings like "Hey There", he learned "to sing with feeling".[549]

Wilson's highest note was D5 in 1966.[426] Initially, his singing was characterized by a pure tenor voice; later in life, he employed this range only rarely.[550] Fearing that a high vocal delivery might fuel perceptions of homosexuality, he avoided it.[551] After the early 1970s, his voice degraded following heavy cigarette and cocaine use,[552] with 15 Big Ones marking the emergence of what biographer Peter Ames Carlin termed Wilson's "baritone croak".[553] In a 1999 interview, Wilson compared his style to Bob Dylan's "harsh, raspy voice".[554]

Mental health

Onset of illness

Wilson is diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder and mild bipolar disorder.[555] Since 1965, he has regularly experienced auditory hallucinations in the form of disembodied voices.[556] Wilson referred to the voices as "heroes and villains" that contributed to "a life of scare".[557]

His family and associates faced challenges in discerning genuine mental health issues from potential manipulative behavior on Wilson's part.[558] Subsequent to his Houston flight incident from December 1964, Marilyn arranged his first psychiatrist visit, where it was ruled that Wilson's condition was due to work-related fatigue.[559] Wilson typically refused counseling, and his family believed his idiosyncrasies stemmed from drug habits or were innate to his personality.[560][561][nb 43] Marilyn countered accusations of neglect on her part, emphasizing her repeated efforts to get him professional help.[563]

According to Wilson, he was introduced to recreational drugs by an acquaintance during a Beach Boys tour.[167][nb 44] His hallucinations emerged early in 1965, about a week after his first time using psychedelics.[565] Loren Schwartz, his supplier, said that Wilson's first dosage was 125 micrograms of "pure Owsley" and resulted in "full-on ego death".[566][nb 45] Mike Love observed signs of irregular behavior in Wilson by July, recalling an incident where Wilson deliberately crashed his car, an act Love deemed out of character.[568] His drug use was initially concealed from his bandmates and family,[569] including Love, who had thought Wilson to be strictly opposed to drugs.[564]

[In mid-1965, Brian had] asked me to come down to Studio B. When we got down there, he said to me, "Let me play something that I hear when I've been on LSD." He sat down at the piano and played one note. He described what he was hearing. That's when I knew he was in trouble.

Wilson, in 1990, attributed LSD to himself developing "a

As Wilson's condition worsened, he grew susceptible to

Post-Landy

Wilson was given the since-retracted diagnosis of

In the late 1980s, Wilson developed facial tics (tardive dyskinesia) symptomatic of excessive psychotropic medications.[578] Therapist Peter Reum stated that Wilson would have deterioriated into a "drooling, palsied mental patient", and potentially died of heart failure had he continued this drug regimen.[301][nb 47] In a 2002 interview, Wilson stated, "I don't regret [the Landy program]. I loved the guy—he saved me."[579] After Wilson sought medical care elsewhere, he was declared to have organic personality disorder.[580][nb 48]

Wilson's mental condition improved in later years, although his auditory hallucinations persisted, especially when performing onstage.

Personal life

Deafness in right ear

At age 11, during a Christmas choir recital, it was found that Wilson had significantly diminished hearing in his right ear.[549] The issue was diagnosed as a nerve impingement.[582] The exact cause remains unclear.[582][583][16][nb 49]

Due to this infirmity, Wilson developed a habit of speaking from the side of his mouth,[587][585] giving the false impression that he had suffered a stroke.[585] He also experiences tinnitus.[588] In the late 1960s, he underwent corrective surgery that was unsuccessful in restoring his hearing.[589]

Relationships and children

Wilson's first serious relationship was with Judy Bowles, a high school student he had met at a baseball game in mid-1961.[590] The couple were engaged during Christmas 1963 and were to be married the following December.[591] She inspired his songs "Judy" (1962), "Surfer Girl" (1963), and, according to some accounts, "The Warmth of the Sun" (1964), the latter being written shortly after they had separated.[592] Around then, he had gradually become romantically involved with singer Marilyn Rovell, whom he had met in August 1962.[593][74] Inspired by a remark from Marilyn's older sister Diane, Wilson wrote "Don't Hurt My Little Sister" (1965) about his early relationship with Marilyn.[594][595]

Wilson and Marilyn were married in December 1964. They had two daughters,

Much of the lyrical content from Pet Sounds reflected early marital strains

In July 1978, Wilson and Marilyn separated, and he filed for divorce in January 1979.[605] Marilyn received custody of their children[606] and a half share of Wilson's songwriting royalties.[410] Wilson continued his relationship with Keil until 1981.[604] After the separation, Wilson dated one of his nurses, Carolyn Williams, until January 1983.[607][nb 51] Singer Linda Ronstadt, in her 2013 memoir Simple Dreams, implied that she had briefly dated Wilson in the 1970s.[604]

Wilson initially dated Melinda Kae Ledbetter from 1986 to late 1989.[611] Ledbetter attributed the premature end of their relationship to interference by Landy.[612] After 1991, he and Ledbetter reconnected and married on February 6, 1995,[613][nb 52] Ledbetter became Wilson's manager.[615] They adopted five children.[616] By 2012, Wilson had six grandchildren, two daughters of Carnie and four sons of Wendy.[365] Ledbetter died on January 30, 2024.[414] In his social media, Wilson declared she "was my savior. She gave me the emotional security I needed to have a career. She encouraged me to make the music that was closer to my heart".[617]

Spirituality

Wilson was raised in a

In the late 1960s, Wilson and his bandmates promoted Transcendental Meditation (TM).[620] By 1968, he had equated religion and meditation,[620] though he ultimately abandoned TM.[259] He described himself in 1976 as having over-diversified his readings,[167] maintaining then that he still believed that the coming of "the great Messiah [...] came in the form of drugs" while acknowledging that his own drug experiences "really didn't work out so well".[621][622][nb 53]

In 2011, he said that while he had spiritual beliefs, he did not follow any particular religion.

Interviews

He is an artist wrapped densely in myth and enigma who, in person, in interview, creates as many questions as he answers. Is this guy crazy, or is he crazy like a fox? Missing a synapse or just as sensitive as a raw nerve ending? Startlingly honest or putting you on? Childishly naïve or a master manipulator?

Wilson has admitted to having a poor memory and occasionally lying in interviews to "test" people.

Cultural impact and influence

Sales achievements

From 1962 to 1979, Wilson wrote or co-wrote over two dozen U.S. Top 40 hits for the Beach Boys, with eleven reaching the top 10, including the number-ones "I Get Around" (1964), "Help Me, Rhonda" (1965), and "Good Vibrations" (1966).[633][nb 56] Three more that he produced, but did not write, were the band's "Barbara Ann" (number 2) in 1965, "Sloop John B" (number 3) in 1966, and "Rock and Roll Music" (number 5) in 1976.[633] Among his other top 10 hits, Wilson co-wrote Jan and Dean's "Surf City" (the first chart-topping surf song) and "Dead Man's Curve" (number 8) in 1963, and the Hondells' "Little Honda" (number 9) in 1964.[634]

Popular music, industry practices, and record production

Wilson is widely regarded as one of the most innovative and significant songwriters of the late 20th century.

The level of creative control that Wilson had asserted over his own record output was unprecedented in the music industry,[638][639][640] leading him to become the first pop artist credited for writing, arranging, producing, and performing his own material.[641] Wilson's autonomy encompassed control over recording studios and personnel, including engineers and the typically intrusive A&R representative. According to biographer James Murphy, Wilson's singular artistic freedom was pivotal in reshaping both the landscape of popular music and the music industry's perception of artistic control.[640]

In addition to being one of the first

Beatles producer George Martin said, "No one made a greater impact on the Beatles than Brian [...] the musician who challenged them most of all."[648][649][nb 58] Jimmy Webb explained, "As far as a major, modern producer who was working right in the middle of the pop milieu, no one was doing what Brian was doing. We didn't even know that it was possible until he did it."[653] David Crosby called Wilson "the most highly regarded pop musician in America. Hands down."[51]

His accomplishments as a producer influenced many others in his field, effectively setting a precedent that allowed subsequent bands and artists to produce their own recording sessions.[642] Following his exercise of total creative autonomy, Wilson ignited an explosion of like-minded California producers, supplanting New York as the center of popular records.[654] Wilson was also a pioneer of "project" recording, where an artist records by himself rather than at an established studio.[642]

The 1967 CBS documentary Inside Pop: The Rock Revolution described Wilson as "one of today's most important pop musicians."[655] Many musicians have voiced admiration for Wilson's work or cited it as an influence, including Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Ray Davies, John Cale, David Byrne, Todd Rundgren, Patti Smith, Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Bruce Springsteen, Randy Newman, Ray Charles, and Chrissie Hynde.[479]

Art pop, pop art, psychedelia, and progressive music

There is no god and Brian Wilson is his son. Brian Wilson stirred up the chords.

Further to his invention of new

Under Wilson's creative leadership, the Beach Boys became major contributors to the development of psychedelic music, although they are rarely credited for this distinction.[667] Christian Matijas-Mecca, in his book about psychedelic rock, credits Wilson, alongside Bob Dylan and the Beatles, for establishing a creative standard that "enabled psychedelic artists to expand their sonic and compositional boundaries", yielding "entirely new" sounds and tone colors.[668] In an editorial piece on sunshine pop, The A.V. Club's Noel Murray recognized Wilson as among "studio rats [that] set the pace for how pop music could and should sound in the Flower Power era: at once starry-eyed and wistful."[669]

Wilson's work with the Beach Boys, especially on Pet Sounds, "Good Vibrations" and Smile, marked the beginnings of

Wilson's detachment from live performance—deploying bandmates as "attractive avatars"—presaged later producer-musicians like Max Martin. Writing in 2016, The Atlantic's Jason Guriel credits Pet Sounds with inventing "the modern pop album" by establishing auteur-driven production, anticipating "the rise of the producer [and] the modern pop-centric era, which privileges producer over artist and blurs the line between entertainment and art."[673][nb 63]

Naïve art, rock/pop division, and outsider music

Wilson's popularity and success is attributed partly to the perceived naïveté of his work and personality.[674][675][676] In music journalist Barney Hoskyns' description, the "particular appeal of Wilson's genius" can be traced to his "singular naivety" and "ingenuousness", alongside his band being "the very obverse of hip".[676] Commenting on the seemingly "campy and corny" quality of the Beach Boys' early records, David Marks said that Wilson had been "dead serious about them all", elaborating, "It's hard to believe that anyone could be that naive and honest, but he was. That's what made those records so successful. You could feel the sincerity in them."[674][675]

The most culturally significant "tragedy" in 1960s rock, according to journalist Richard Goldstein, was Wilson's failure to overcome his insecurities and realize "his full potential as a composer" after having anticipated developments such as electronica and minimalism.[677] Writing in 1981, sociomusicologist Simon Frith identified Wilson's withdrawal in 1967, along with Phil Spector's self-imposed retirement in 1966, as the catalysts for the "rock/pop split that has afflicted American music ever since".[678]

Speaking in a 1997 interview, musician Sean O'Hagan felt that rock music's domination of mass culture following the mid-1960s had the effect of artistically stifling contemporary pop composers who, until then, had been guided by Wilson's increasingly ambitious creative advancements.[679] In her article which dubbed him "the godfather of sensitive pop", music journalist Patricia Cárdenas credits Wilson with ultimately inspiring many musicians to value the craft of pop songwriting as much as "the primal, hard-driving rock 'n' roll the world had come to know since then."[680]

"I guess I just wasn't made for these times," he had declared on Pet Sounds, and the song had become the overture for a decades-long saga that would be, in its way, just as influential as Pet Sounds had been. [...] Ultimately, Brian's public suffering had transformed him from a musical figure into a cultural one.

By the mid-1970s, Wilson had tied with ex-

Ultimately, Wilson became regarded as the most famous outsider musician.[684][685] Author Irwin Chusid, who codified the term "outsider music", noted Wilson as a potentially unconvincing example of the genre due to Wilson's commercial successes, but argued that the musician should be considered an outsider due to his "tormented" background, past issues with drug dependencies, and unorthodox songwriting.[684]

Alternative music and continued cultural resonance

Wilson has also been declared the "godfather" of

Later in the 20th century, Wilson was credited with "godfathering" an era of independently produced music that was heavily indebted to his melodic sensibilities,

Many of the most popular acts of the 1980s and 1990s recorded songs that celebrated or referenced Wilson's music, including R.E.M., Bruce Springsteen,

Through acts such as Panda Bear, and especially his 2007 album Person Pitch, Wilson began to be recognized for his continued impact on the indie music vanguard.[695] In 2009, Pitchfork ran an editorial feature that traced the development of nascent indie music scenes, and chillwave in particular, to the themes of Wilson's songs and his reputation for being an "emotionally fragile dude with mental health problems who coped by taking drugs."[698]

Wilson's influence continues to be attributed to modern dream pop acts such as Au Revoir Simone, Wild Nothing, Alvvays, and Lana Del Rey.[695] In 2022, She & Him, accompanied by the release of Melt Away: A Tribute to Brian Wilson, embarked on a concert tour dedicated to renditions of Wilson's songs.[699]

Authorized documentary films

- Brian Wilson: I Just Wasn't Made for These Times, directed by Don Was, premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January 1995.[326] It features new interviews with Wilson and many other musicians, including Linda Ronstadt and Sonic Youth's Thurston Moore, who discuss Wilson's life and his music achievements.[700]

- Beautiful Dreamer: Brian Wilson and the Story of Smile, directed by David Leaf, premiered on the Showtime network in October 2004.[701] It includes interviews with Wilson and dozens of his associates, albeit none of his surviving bandmates from the Beach Boys, who declined to appear in the film.[702]

- Tribeca Film Festival in June 2021.[703] It is focused on the previous two decades of Wilson's life, with appearances from Bruce Springsteen, Elton John, Jim James, Nick Jonas, Taylor Hawkins, Don Was, and Jakob Dylan.[704]

Accolades

Awards and honors

- Nine-time Grammy Award nominee, two-time winner.[705]

- 2005: Mrs. O'Leary's Cow".[706]

- 2013: Best Historical Album for The Smile Sessions.[707]

- 2005:

- 1988: Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member of the Beach Boys.[307]

- 2000: Songwriters Hall of Fame, inducted by Paul McCartney,[708] who referred to him as "one of the great American geniuses".[709]

- 2006: UK Music Hall of Fame, inducted by Pink Floyd guitarist David Gilmour.[710]

- 2003: Ivor Novello International Award for his contributions to popular music.[354]

- 2003: Honorary doctorate of music from Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts.[354]

- 2004: BMI Icon at the 52nd annual BMI Pop Awards, being saluted for his "unique and indelible influence on generations of music makers."[711]

- 2005: MusiCares Person of the Year, for his artistic and philanthropic accomplishments[365]

- 2007: Hollywood Bowl Hall of Fame[480]

- 2007: Kennedy Center Honors committee recognized Wilson for a lifetime of contributions to American culture through the performing arts in music.[712]

- 2008: Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.[713][714]

- 2011: George and Ira Gershwin Award at UCLA Spring Sing.[715]

- 2016: Golden Globe nomination for "One Kind of Love" from Love & Mercy.[716]

Polls and critics' rankings

- In 1966, Wilson was ranked number four in NME's "World Music Personality" reader's poll—about 1,000 votes ahead of Bob Dylan and 500 behind John Lennon.[717]

- In 2008, Wilson was ranked number 52 in Rolling Stone's list of the "100 Greatest Singers of All Time". He was described in his entry as "the ultimate singer's songwriter" of the mid-1960s.[718]

- In 2012, Wilson was ranked number eight in NME's list of the "50 Greatest Producers Ever", elaborating "few consider quite how groundbreaking Brian Wilson's studio techniques were in the mid-60s".[719]

- In 2015, Wilson was ranked number 12 in Rolling Stone's list of the "100 Greatest Songwriters of All Time".[720]

- In 2020, Brian Wilson Presents Smile was ranked number 399 on Rolling Stone's list of "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time".[721]

- In 2022, Wilson was ranked second in Ultimate Classic Rock's list of the best producers in rock history.[722]

- In 2023, Wilson was ranked number 57 in Rolling Stone's list of the "200 Greatest Singers of All Time", elaborating that "he is so renowned for his producing and songwriting skills that his gifts as a vocalist are often overlooked".[723]

Discography

- Brian Wilson (1988)

- I Just Wasn't Made for These Times (1995) (soundtrack)

- Orange Crate Art (1995) (with Van Dyke Parks)

- Imagination (1998)

- Gettin' In over My Head (2004)

- Brian Wilson Presents Smile (2004)

- What I Really Want for Christmas (2005)

- That Lucky Old Sun (2008)

- Brian Wilson Reimagines Gershwin (2010)

- In the Key of Disney (2011)

- No Pier Pressure (2015)

- At My Piano (2021)

Filmography

Film

| Year | Title | Role |

|---|---|---|

| 1965 | The Girls on the Beach | himself (with the Beach Boys) |

| 1965 | The Monkey's Uncle | himself (with the Beach Boys) |

| 1987 | The Return of Bruno | himself |

| 1993 | Theremin: An Electronic Odyssey | himself |

| 1995 | Brian Wilson: I Just Wasn't Made for These Times | himself |

| 2004 | Beautiful Dreamer: Brian Wilson and the Story of Smile | himself |

| 2006 | Tales of the Rat Fink | The Surfite (voice) |

| 2014 | Love & Mercy | himself (archival) |

| 2018 | Echo in the Canyon | himself |

| 2021 | Brian Wilson: Long Promised Road | himself |

Television

| Year | Title | Role |

|---|---|---|

| 1967 | Inside Pop: The Rock Revolution | himself |

| 1988 | The New Leave It to Beaver | Mr. Hawthorne |

| 1988 | Full House | himself (with the Beach Boys) |

| 2005 | Duck Dodgers | himself (voice) |

See also

- Pet Projects: The Brian Wilson Productions

- Playback: The Brian Wilson Anthology

- List of people with absolute pitch

- List of people with bipolar disorder

- List of recluses

- List of unreleased songs recorded by the Beach Boys

Notes

- Marine Corps Hymn".[9]

- ^ According to his mother, "The [accordion instructor] said, 'I don't think he's reading. He hears it just once and plays the whole thing perfectly.'"[9]

- ^ His 2016 memoir says his "first real job" was at a lumberyard.[26]

- ^ Their rooms had been designed for large orchestras and ensembles of the 1950s, not small rock groups.[50]

- ^ This includes records by the Honeys, Jan and Dean, the Survivors, Sharon Marie, the Timers, the Castells ("I Do"), Bob Norberg, Vickie Kocher, Gary Usher, Christian, Paul Petersen ("She Rides with Me"), and Larry Denton ("Endless Sleep").[73] He also founded Brian Wilson Productions, a record production company with offices on Sunset Boulevard, and Ocean Music, a publishing entity for his work with artists outside the Beach Boys.[83]

- ^ This was the first time Wilson had skipped concert dates with the Beach Boys since 1963.[96] Although he continued to make sporadic appearances at gigs, the Houston show marked his last as a regular member of the touring group until 1976.[98]

- ^ Songwriters Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil recalled that Wilson had confided in them about considering retirement from the music industry, changing his mind after hearing Spector's latest hit record, "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'."[104] In an interview from August 1966, Wilson states, "I never wanted to quit the music business. I just wanted to get off the road, which I did."[105] Photographer Ed Roach said that Brian had felt overshadowed by the audience's enthusiastic response to his brother Dennis during live performances.[106]

- ^ Wilson rejoined the live group for one-off occasions in February, March, July, and October 1965.[108]

- ^ Sources differ on the move-in date: White cites December,[127] while Badman specifies October.[126]

- ^ Marilyn cited Wilson's desire for a larger home,[151] while Badman writes that the move aimed to distance them from his entourage of "hanger-ons".[149] Marilyn later installed security measures, including a brick wall and electronic gate.[152]

- ^ Dennis also refuted claims that the Beach Boys excluded Brian, explaining that he repeatedly visited Brian's home to prioritize his health over recording.[180]

- ^ David Leaf, writing in his 1978 biography of the band, said that Wilson's family and friends had dismissed these incidents as jokes.[191]