MHC class I

| MHC class I | |

|---|---|

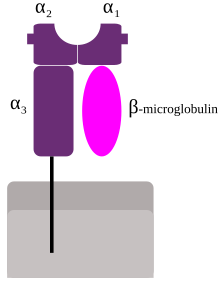

Schematic representation of MHC class I | |

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | MHC class I |

| Membranome | 63 |

MHC class I molecules are one of two primary classes of

In humans, the HLAs corresponding to MHC class I are HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C.

Function

Class I MHC molecules bind peptides generated mainly from degradation of cytosolic proteins by the proteasome. The MHC I:peptide complex is then inserted via endoplasmic reticulum into the external plasma membrane of the cell. The epitope peptide is bound on extracellular parts of the class I MHC molecule. Thus, the function of the class I MHC is to display intracellular proteins to cytotoxic T cells (CTLs). However, class I MHC can also present peptides generated from exogenous proteins, in a process known as cross-presentation.

A normal cell will display peptides from normal cellular protein turnover on its class I MHC, and CTLs will not be activated in response to them due to central and peripheral tolerance mechanisms. When a cell expresses foreign proteins, such as after viral infection, a fraction of the class I MHC will display these peptides on the cell surface. Consequently, CTLs specific for the MHC:peptide complex will recognize and kill presenting cells.

Alternatively, class I MHC itself can serve as an inhibitory ligand for

PirB and visual plasticity

Paired-immunoglobulin-like receptor B (PirB), an MHCI-binding receptor, is involved in the regulation of visual plasticity.[5] PirB is expressed in the central nervous system and diminishes ocular dominance plasticity in the developmental critical period and adulthood.[5] When the function of PirB was abolished in mutant mice, ocular dominance plasticity became more pronounced at all ages.[5] PirB loss of function mutant mice also exhibited enhanced plasticity after monocular deprivation during the critical period.[5] These results suggest PirB may be involved in modulation of synaptic plasticity in the visual cortex.

Structure

MHC class I molecules are heterodimers that consist of two polypeptide chains, α and

While a high-affinity peptide and the B2M subunit are normally required to maintain a stable

Synthesis

The peptides are generated mainly in the

Translocation and peptide loading

The peptide translocation from the cytosol into the lumen of the ER is accomplished by the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP). TAP is a member of the ABC transporter family and is a heterodimeric multimembrane-spanning polypeptide consisting of TAP1 and TAP2. The two subunits form a peptide binding site and two ATP binding sites that face the cytosol. TAP binds peptides on the cytoplasmic side and translocates them under ATP consumption into the lumen of the ER. The MHC class I molecule is then, in turn, loaded with peptides in the lumen of the ER.

The peptide-loading process involves several other molecules that form a large multimeric complex called the

Once the peptide is loaded onto the MHC class I molecule, the complex dissociates and it leaves the ER through the

Peptide removal

Peptides that fail to bind MHC class I molecules in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) are removed from the ER via the sec61 channel into the cytosol,[16][17] where they might undergo further trimming in size, and might be translocated by TAP back into ER for binding to a MHC class I molecule.

For example, an interaction of sec61 with bovine albumin has been observed.[18]

Effect of viruses

MHC class I molecules are loaded with peptides generated from the degradation of

The fate of the virus-infected cell is almost always induction of

Genes and isotypes

- Very polymorphic

- Less polymorphic

Evolutionary history

The MHC class I genes originated in the most

Birth-and-death of MHC class I genes

Birth-and-death evolution asserts that gene duplication events cause the genome to contain multiple copies of a gene which can then undergo separate evolutionary processes. Sometimes these processes result in pseudogenization (death) of one copy of the gene, though sometimes this process results in two new genes with divergent function.[21] It is likely that human MHC class Ib loci (HLA-E, -F, and -G) as well as MHC class I pseudogenes arose from MHC class Ia loci (HLA-A, -B, and -C) in this birth-and-death process.[22]

References

- PMID 14511229.

- ^ S2CID 41765680.

- ^ http://users.rcn.com/jkimball.ma.ultranet/BiologyPages/H/HLA.html#Class_I_Histocompatibility_Molecules Archived 2016-02-04 at the Wayback Machine Kimball's Biology Pages, Histocompatibility Molecules

- S2CID 9278263.

- ^ S2CID 1860730.

- PMID 16297661.

- PMID 2198471.

- PMID 2199065.

- PMID 37310998.

- PMID 30315122.

- S2CID 41095551.

- S2CID 4447406.

- PMID 15286279.

- S2CID 29762957.

- S2CID 28659293.

- PMID 10933400.

- PMID 14644099.

- PMID 15546887.

- PMID 18083706.

- PMID 26337052.

- PMID 16285855.

- PMID 7700152.

External links

- Histocompatibility+Antigens+Class+I at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- MHC+Class+I+Genes at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)