Condensin

Condensins are large protein complexes that play a central role in chromosome assembly and segregation during mitosis and meiosis (Figure 1).[1][2] Their subunits were originally identified as major components of mitotic chromosomes assembled in Xenopus egg extracts.[3]

Subunit composition

Eukaryotic types

Many

| Complex | Subunit | Classification | Vertebrates | D. melanogaster | C. elegans | S. cerevisiae | S. pombe | A. thaliana | C. merolae |

T. thermophila |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| condensin I & II | SMC2 | SMC ATPase | CAP-E/SMC2 | SMC2 | MIX-1 | Smc2 | Cut14 | CAP-E1&-E2 | SMC2 | Scm2 |

| condensin I & II | SMC4 | SMC ATPase | CAP-C/SMC4 | SMC4/Gluon | SMC-4 | Smc4 | Cut3 | CAP-C | SMC4 | Smc4 |

| condensin I | CAP-D2 | HEAT-IA | CAP-D2 | CAP-D2 | DPY-28 | Ycs4 | Cnd1 | CAB72176 | CAP-D2 | Cpd1&2 |

| condensin I | CAP-G | HEAT-IB | CAP-G | CAP-G | CAP-G1 | Ycg1 | Cnd3 | BAB08309 | CAP-G | Cpg1 |

| condensin I | CAP-H | kleisin | CAP-H | CAP-H/Barren | DPY-26 | Brn1 | Cnd2 | AAC25941 | CAP-H | Cph1,2,3,4&5 |

| condensin II | CAP-D3 | HEAT-IIA | CAP-D3 | CAP-D3 | HCP-6 | - | - | At4g15890.1 | CAP-D3 | - |

| condensin II | CAP-G2 | HEAT-IIB | CAP-G2 | - | CAP-G2 | - | - | CAP-G2/HEB1 | CAP-G2 | - |

| condensin II | CAP-H2 | kleisin | CAP-H2 | CAP-H2 | KLE-2 | - | - | CAP-H2/HEB2 | CAP-H2 | - |

| condensin IDC | SMC4 variant | SMC ATPase | - | - | DPY-27 | - | - | - | - | - |

The core subunits condensins (SMC2 and SMC4) are conserved among all eukaryotic species that have been studied to date. The non-SMC subunits unique to condensin I are also conserved among eukaryotes, but the occurrence of the non-SMC subunits unique to condensin II is highly variable among species.

- For instance, the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster does not have the gene for the CAP-G2 subunit of condensin II.[9] Other insect species often lack the genes for the CAP-D3 and/or CAP-H subunits, too, indicating that the non-SMC subunits unique to condensin II have been under high selection pressure during insect evolution.[10]

- The dosage compensation.[11]In this complex, known as condensin IDC, the authentic SMC4 subunit is replaced with its variant, DPY-27 (Figure 2).

- Some species, like Cyanidioschyzon merolae, whose genome size is comparable to those of the yeast, has both condensins I and II.[14]Thus, there is no apparent relationship between the occurrence of condensin II and the size of eukaryotic genomes.

- The paralogs for two of its regulatory subunits (CAP-D2 and CAP-H), and some of them specifically localize to either the macronucleus (responsible for gene expression) or the micronucleus (responsible for reproduction).[15] Thus, this species has multiple condensin I complexes that have different regulatory subunits and display distinct nuclear localization.[16]This is a very unique property that is not found in other species.

Prokaryotic types

Prokaryotic species also have condensin-like complexes that play an important role in chromosome (nucleoid) organization and segregation. The prokaryotic condensins can be classified into two types: SMC-ScpAB[17] and MukBEF.[18] Many eubacterial and archaeal species have SMC-ScpAB, whereas a subgroup of eubacteria (known as Gammaproteobacteria) including Escherichia coli has MukBEF. ScpA and MukF belong to a family of proteins called "kleisins",[7] whereas ScpB and MukE have recently been classified into a new family of proteins named "kite".[19]

| Complex | Subunit | Classification | B. subtilis |

Caulobacter | E.coli

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMC-ScpAB | SMC | ATPase | SMC/BsSMC | SMC | - |

| SMC-ScpAB | ScpA | kleisin | ScpA | ScpA | - |

| SMC-ScpAB | ScpB | kite | ScpB | ScpB | - |

| MukBEF | MukB | ATPase | - | - | MukB |

| MukBEF | MukE | kite | - | - | MukE |

| MukBEF | MukF | kleisin | - | - | MukF |

Despite highly divergent primary structures of their corresponding subunits between SMC-ScpAB and MukBEF, it is reasonable to consider that the two complexes play similar if not identical functions in prokaryotic chromosome organization and dynamics, based on their molecular architecture and their defective cellular phenotypes. Both complexes are therefore often called prokaryotic (or bacterial) condensins. Recent studies report the occurrence of a third complex related to MukBEF (termed MksBEF) in some bacterial species.[20]

Molecular mechanisms

Molecular structures

SMC dimers that act as the core subunits of condensins display a highly characteristic V-shape, each arm of which is composed of anti-parallel coiled-coils (Figure 3; see

Early studies elucidated the structure of parts of bacterial condensins, such as MukBEF[25][26] and SMC-ScpA.[27][28] In eukaryotic complexes, several structures of subcomplexes and subdomains have been reported, including the hinge and arm domains of an SMC2-SMC4 dimer,[29][30] a CAP-G(ycg1)/CAP-H(brn1) subcomplex,[31][32] and a CAP-D2(ycs4)/CAP-H(brn1) subcomplex.[24] A recent cryo-EM study has shown that condensin undergoes large conformational changes that are coupled with ATP-binding and hydrolysis by its SMC subunits.[33] On the other hand, fast-speed atomic force microscopy has demonstrated that the arms of an SMC dimer is far more flexible than was expected.[34]

Molecular activities

Condensin I purified from

Most recently, single-molecule experiments have demonstrated that budding yeast condensin I is able to translocate along dsDNA (motor activity)[42] and to "extrude" DNA loops (loop extrusion activity)[43] in an ATP hydrolysis-dependent manner. In the latter experiments, the activity of individual condensin complexes on DNA was visualized by real-time fluorescence imaging, revealing that condensin I indeed is a fast loop-extruding motor and that a single condensin I complex can extrude 1,500 bp of DNA per second in a strictly ATP-dependent manner. It has been proposed that condensin I anchors DNA between Ycg1-Brn1 subunits[31] and pulls DNA asymmetrically to form large loops. Moreover, it has been shown that condensin complexes can traverse each other, forming dynamic loop structures and changing their sizes.[44]

It is unknown how condensins might act on nucleosomal DNA. Recent development of a reconstitution system has identified the histone chaperone FACT as an essential component of condensin I-mediated chromosome assembly in vitro, providing an important clue to this problem.[45] It has also been shown that condensins can assemble chromosome-like structures in cell-free extracts even under the condition where nucleosome assembly is largely suppressed.[46] This observation indicates that condensins can work at least in part on non-nucleosomal DNA in a physiological setting.

How similar and how different are the molecular activities of condensin I and condensin II? Both share two SMC subunits, but each has three unique non-SMC subunits (Figure 2). A fine-tuned balance between the actions of these non-SMC subunits could determine the differences in the rate of loop extrusion [47] and the activity of mitotic chromosome assembly [48][49][50][51] of the two complexes. By introducing different mutations, it is possible to convert condensin I into a complex with condensin II-like activities and vice versa.[51]

Mathematical modeling

Several attempts on mathematical modeling and computer simulation of mitotic chromosome assembly, based on molecular activities of condensins, have been reported. Representative ones include modeling based on loop extrusion,[52] stochastic pairwise contacts[53] and a combination of looping and inter-condensin attractions.[54]

Functions in chromosome assembly and segregation

Mitosis

In human tissue culture cells, the two condensin complexes are regulated differently during the mitotic cell cycle (Figure 4).[55][56] Condensin II is present within the cell nucleus during interphase and participates in an early stage of chromosome condensation within the prophase nucleus. On the other hand, condensin I is present in the cytoplasm during interphase, and gains access to chromosomes only after the nuclear envelope breaks down (NEBD) at the end of prophase. During prometaphase and metaphase, condensin I and condensin II cooperate to assemble rod-shaped chromosomes, in which two sister chromatids are fully resolved. Such differential dynamics of the two complexes is observed in Xenopus egg extracts,[57] mouse oocytes,[58] and neural stem cells,[59] indicating that it is part of a fundamental regulatory mechanism conserved among different organisms and cell types. It is most likely that this mechanism ensures the ordered action of the two complexes, namely, condensin II first and condensin I later.[60]

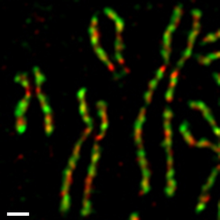

On metaphase chromosomes, condensins I and II are both enriched in the central axis in a non-overlapping fashion (Figure 5). Depletion experiments in vivo[4][59][61] and immunodepletion experiments in Xenopus egg extracts[57] demonstrate that the two complexes have distinct functions in assembling metaphase chromosomes. Cells deficient in condensin functions are not arrested at a specific stage of cell cycle, displaying chromosome segregation defects (i.e., anaphase bridges) and progressing through abnormal cytokinesis.[62][63]

The relative contribution of condensins I and II to mitosis varies among different eukaryotic species. For instance, each of condensins I and II plays an essential role in embryonic development in mice.

| species | M. musculus |

D. melanogaster |

C. elegans |

S. cerevisiae |

S. pombe |

A. thaliana |

C. merolae

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| genome size | ~2,500 Mb | 140 Mb | 100 Mb | 12 Mb | 14 Mb | 125 Mb | 16 Mb |

| condensin I | essential | essential | minor | essential | essential | essential | essential |

| condensin II | essential | non-essential | essential | - | - | non-essential | non-essential |

It has recently become possible that cell cycle-dependent structural changes of chromosomes are monitored by a genomics-based method known as Hi-C (High-throughput chromosome conformation capture).[65] The impact of condensin deficiency on chromosome conformation has been addressed in budding yeast,[66][67] fission yeast,[68][69] and the chicken DT40 cells.[70] The outcome of these studies strongly supports the notion that condensins play crucial roles in mitotic chromosome assembly and that condensin I and II have distinct functions in this process. Moreover, quantitative imaging analyses allow researchers to count the number of condensin complexes present on human metaphase chromosomes.[71]

Meiosis

Condensins also play important roles in chromosome assembly and segregation in

Chromosomal functions outside of mitosis or meiosis

Recent studies have shown that condensins participate in a wide variety of chromosome functions outside of mitosis or meiosis.[60]

- In tRNA genes.[78]

- In fission yeast, condensin I is involved in the regulation of replicative checkpoint[79] and clustering of genes transcribed by RNA polymerase III.[80]

- In dosage compensation.[81]

- In D. melanogaster, condensin II subunits contribute to the dissolution of polytene chromosomes[82] and the formation of chromosome territories[83] in ovarian nurse cells. Evidence is available that they negatively regulate transvection in diploid cells. It has also been reported that condensin I components are required to ensure correct gene expression in neurons following cell-cycle exit.[84]

- In A. thaliana, condensin II is essential for tolerance of excess boron stress, possibly by alleviating DNA damage.[64]

- In mammalian cells, it is likely that condensin II is involved in the regulation of interphase chromosome architecture and function. For instance, in human cells, condensin II participates in the initiation of sister chromatid resolution during S phase, long time before mitotic prophase when sister chromatids become cytologically visible.[85]

- In mouse interphase nuclei, pericentromeric heterochromatin on different chromosomes associates with each other, forming a large structure known as chromocenters. Cells deficient in condensin II, but not in condensin I, display hyperclustering of chromocenters, indicating that condensin II has a specific role in suppressing chromocenter clustering.[59]

- Whilst early studies suggested the possibility that condensins may directly participate in regulating gene expression, some recent studies argue against this hypothesis.[86][87]

- Mutants of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe were obtained that had a temperature sensitive and/or DNA damage sensitive phenotype.[88] Some of these mutants were defective in the HEAT subunits of condensin indicating that the HEAT subunits are required for DNA repair.[88]

Posttranslational modifications and cell cycle regulation

Condensin subunits are subject to various

Phosphorylation by

have been reported.Several mitotic kinases,

It has been reported that the CAP-H2 subunit of condensin II is degraded in Drosophila through the action of the SCFSlimb ubiquitin ligase.[102]

Relevance to diseases

It was demonstrated that MCPH1, one of the proteins responsible for human primary

Evolutionary implications

Prokaryotes have primitive types of condensins,[17][18] indicating that the evolutionary origin of condensins precede that of histones. The fact that condensins I and II are widely conserved among extant eukaryotic species strongly implicates that the last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA) had both complexes.[60] It is therefore reasonable to speculate that some species such as fungi have lost condensin II during evolution.

Then why do many eukaryotes have two different condensin complexes? As discussed above, the relative contribution of condensins I and II to mitosis varies among different organisms. They play equally important roles in mammalian mitosis, whereas condensin I has a predominant role over condensin II in many other species. In those species, condensin II might have been adapted for various non-essential functions other than mitosis.[64][82] Although there is no apparent relationship between the occurrence of condensin II and the size of genomes, it seems that the functional contribution of condensin II becomes big as the genome size increases.[14][59] A recent, comprehensive Hi-C study argues from an evolutionary point of view that condensin II acts as a determinant that converts post-mitotic Rabl configurations into interphase chromosome territories.[108] The relative contribution of the two condensin complexes to mitotic chromosome architecture also change during development, making an impact on the morphology of mitotic chromosomes.[57] Thus, the balancing act of condensins I and II is apparently fine-tuned in both evolution and development.

Relatives

Eukaryotic cells have two additional classes of SMC protein complexes. Cohesin contains SMC1 and SMC3 and is involved in sister chromatid cohesion. The SMC5/6 complex contains SMC5 and SMC6 and is implicated in recombinational repair.

See also

- chromosome

- nucleoid

- mitosis

- meiosis

- cell cycle

- cohesin

- SMC protein

- ATPase

- HEAT repeat

- Topoisomerase II

- DNA supercoil

References

- PMID 26919425.

- S2CID 28241964.

- S2CID 15061740.

- ^ S2CID 18811084.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 20398243.

- PMID 31577909.

- ^ PMID 12667442.

- PMID 11042144.

- PMID 23637630.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 31270536.

- ^ PMID 19119011.

- ^ PMID 10485849.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 10811823.

- ^ PMID 23783031.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 29237819.

- PMID 30893010.

- ^ PMID 12065423.

- ^ PMID 10545099.

- PMID 26585514.

- PMID 21752107.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 9744887.

- PMID 11815634.

- PMID 17268547.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 31226277.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 15902272.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 4608756.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 21584205.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 23541893.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 20139420.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 25557547.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 28988770.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 30858338.

- PMID 32661420.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 26904946.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 15876604.

- S2CID 16671030.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 11914278.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 19481522.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 9774278.

- S2CID 34081946.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 10078994.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 28882993.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 29472443.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 212407150.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ S2CID 8332012.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 28522692.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 32445620.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 25850674.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 35045152.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 35983835.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 38088875.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 27192037.

- PMID 25922992.

- PMID 29912867.

- PMID 15146063.

- PMID 15572404.

- ^ PMID 21715560.

- ^ PMID 21795393.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 25474630.

- ^ PMID 22855829.

- PMID 22344259.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 7957061.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 12919682.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 21917552.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 24200812.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 28825700.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 28729434.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 28825727.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 28991264.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 29348367.

- PMID 29632028.

- PMID 14662740.

- PMID 18927632.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 19104074.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 15557118.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 25961503.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 16507999.

- PMID 18708579.

- S2CID 4332524.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 19910488.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 26030525.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ S2CID 5154197.

- PMID 22956908.

- PMID 32255428.

- PMID 23401001.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 29970489.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 30230473.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ a b Xu X, Nakazawa N, Yanagida M. Condensin HEAT subunits required for DNA repair, kinetochore/centromere function and ploidy maintenance in fission yeast. PLoS One. 2015 Mar 12;10(3):e0119347. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119347. PMID 25764183; PMCID: PMC4357468

- PMID 36268993.

- ^ PMID 20703077.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 25691469.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 29791843.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 36511239.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 17356064.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 21540296.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 17066080.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 21498573.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 25605712.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 25109385.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 24934155.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 14653995.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 23530065.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 21911480.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 16434882.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 27737959.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 17640884.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 27737961.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 34045355.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link

External links

- condensin at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)