Edward Witten

Edward Witten | |

|---|---|

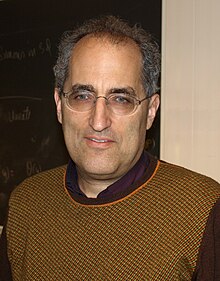

Witten in 2008 | |

| Born | August 26, 1951 |

| Education |

|

| Known for | CSW rules Witten conjecture Witten zeta function Hanany–Witten transition Twistor string theory Chern–Simons theory Positive energy theorem Witten–Veneziano mechanism |

| Spouse | |

| Thesis | Some Problems in the Short Distance Analysis of Gauge Theories (1976) |

| Doctoral advisor | David Gross[2] |

| Other academic advisors | Sidney Coleman[3] Michael Atiyah[3] |

| Doctoral students | Jonathan Bagger (1983) Cumrun Vafa (1985) Xiao-Gang Wen (1987) Dror Bar-Natan (1991) Shamit Kachru (1994) Eva Silverstein (1996) Sergei Gukov (2001) |

| Website | ias |

Edward Witten (born August 26, 1951) is an American

Early life and education

Witten was born on August 26, 1951, in

Witten attended the Park School of Baltimore (class of 1968), and received his Bachelor of Arts degree with a major in history and minor in linguistics from Brandeis University in 1971.[14]

He had aspirations in journalism and politics and published articles in both The New Republic and The Nation in the late 1960s.[15][16] In 1972, he worked for six months on George McGovern's presidential campaign.[17]

Witten attended the

Research

Fields medal work

Witten was awarded the Fields Medal by the International Mathematical Union in 1990.[21]

In a written address to the ICM, Michael Atiyah said of Witten:[5]

Although he is definitely a physicist (as his list of publications clearly shows) his command of mathematics is rivaled by few mathematicians, and his ability to interpret physical ideas in mathematical form is quite unique. Time and again he has surprised the mathematical community by a brilliant application of physical insight leading to new and deep mathematical theorems ... He has made a profound impact on contemporary mathematics. In his hands physics is once again providing a rich source of inspiration and insight in mathematics.[5]

As an example of Witten's work in pure mathematics, Atiyah cites his application of techniques from

Another result for which Witten was awarded the Fields Medal was his proof in 1981 of the

A third area mentioned in Atiyah's address is Witten's work relating

M-theory

By the mid 1990s, physicists working on

Speaking at the string theory conference at

Other work

Another of Witten's contributions to physics was to the result of gauge/gravity duality. In 1997,

In collaboration with

With Anton Kapustin, Witten has made deep mathematical connections between S-duality of gauge theories and the geometric Langlands correspondence.[38] Partly in collaboration with Seiberg, one of his recent interests includes aspects of field theoretical description of topological phases in condensed matter and non-supersymmetric dualities in field theories that, among other things, are of high relevance in condensed matter theory. In 2016, he has also brought tensor models to the relevance of holographic and quantum gravity theories, by using them as a generalization of the Sachdev–Ye–Kitaev model.[39]

Witten has published influential and insightful work in many aspects of quantum field theories and mathematical physics, including the physics and mathematics of anomalies, integrability, dualities, localization, and homologies. Many of his results have deeply influenced areas in theoretical physics (often well beyond the original context of his results), including string theory, quantum gravity and topological condensed matter.[40]

Awards and honors

Witten has been honored with numerous awards including a

In an informal poll at a 1990 cosmology conference, Witten received the largest number of mentions as "the smartest living physicist".[51]

Personal life

Witten has been married to Chiara Nappi, a professor of physics at Princeton University, since 1979.[52] They have two daughters and a son. Their daughter Ilana B. Witten is a neuroscientist at Princeton University,[53] and daughter Daniela Witten is a biostatistician at the University of Washington.[54]

Witten sits on the board of directors of

Selected publications

- Some Problems in the Short Distance Analysis of Gauge Theories. Dissertation.)

- Sam B. Treiman, Edward Witten, Bruno Zumino. Current Algebra and Anomalies: A Set of Lecture Notes and Papers. World Scientific, 1985.

- ISBN 978-0-521-35752-4.

- Green, M., John H. Schwarz, and E. Witten. Superstring Theory. Vol. 2, Loop Amplitudes, Anomalies and Phenomenology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0-521-35753-1.

- Quantum fields and strings: a course for mathematicians. Vols. 1, 2. Material from the Special Year on Quantum Field Theory held at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, NJ, 1996–1997. Edited by ISBN 0-8218-1198-3, 81–06 (81T30 81Txx).

References

- ^ "Announcement of 2016 Winners". World Cultural Council. June 6, 2016. Archived from the original on June 7, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- ISBN 0-465-09275-6.

- ^ a b c "Edward Witten – Adventures in physics and math (Kyoto Prize lecture 2014)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 23, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ a b "Edward Witten". Institute for Advanced Study. December 9, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ a b c Atiyah, Michael (1990). "On the Work of Edward Witten" (PDF). Proceedings of the International Congress of Mathematicians. pp. 31–35. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 1, 2017.

- ^ Michael Atiyah. "On the Work of Edward Witten" (PDF). Mathunion.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 1, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- ^ Duff 1998, p. 65

- ^ J J O'Connor; E F Robertson (September 2009). "Edward Witten - Biography". Maths History. University of St Andrews. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "LDB Appoints Jesse A. Witten to the LDB Legal Advisory Board". Brandeis Center. October 20, 2020.

- ^ Celia Witten at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- ^ "Celia Witten, M.D., Ph.D." The University of Texas at Austin, College of Pharmacy.

- ^ "Obituary for Lorraine Witten". The Cincinnati Enquirer. February 10, 1987. p. 13.

- ISBN 978-0-946653-84-3.

- ^ "Edward Witten (1951)". www.nsf.gov. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- ^ Witten, Edward (October 18, 1969). "Are You Listening, D.H. Lawrence?". The New Republic.

- ^ Witten, Edward (December 16, 1968). "The New Left". The Nation.

- ^ Farmelo, Graham (May 2, 2019). "'The Universe Speaks in Numbers' – Interview 5". Graham Farmelo. Archived from the original on May 3, 2019. Retrieved August 25, 2020. Alt URL

- ^ "Edward Witten". www.aip.org. February 24, 2022. Retrieved June 21, 2022.

- ^ Witten, E. (1976). Some problems in the short distance analysis of gauge theories.

- ^ Interview by Hirosi Ooguri Archived March 29, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Notices of the American Mathematical Society, May 2015, pp. 491–506.

- ^ "Edward Witten" (PDF). 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 4, 2012. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ S2CID 43230714

- S2CID 14951363.

- S2CID 123376541.

- S2CID 1035111.

- S2CID 54217085.

- S2CID 59473203.

- ISSN 0010-3616.

- ^ .

- ^ ISBN 978-3-662-50183-2.

- ^ Witten, E. (March 13–18, 1995). Some problems of strong and weak coupling. physics.usc.edu. Future Perspectives in String Theory. Los Angeles: University of Southern California. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- S2CID 16790997.

- .

- S2CID 10882387.

- S2CID 668885.

- S2CID 14361074.

- MR 1339810

- S2CID 30505126.

- S2CID 118412962.

- ^ Stiftung, Joachim Herz (July 3, 2023). "News". Joachim Herz Stiftung. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "The President's National Medal of Science: Recipient Details". www.nsf.gov. National Science Foundation. 2003. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "Il premio Pitagora al fisico teorico Witten". Il Crotonese (in Italian). September 23, 2005. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011.

- ^ "Current Fellows". royalsociety.org. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "Fellows". June 21, 2016. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ^ "Fellows of the American Mathematical Society". American Mathematical Society. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "Edward Witten". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ "Edward Witten". www.nasonline.org. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ "Penn's 2022 Commencement Speaker and Honorary Degree Recipients". Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- Michael Turner, James Peebles, Alan Guth and Andrei Linde, to nominate the smartest living physicist. Edward Witten got the most votes (with Steven Weinberg the runner-up). Some considered Witten to be in the same league as Einstein and Newton." See "Physics Titan Edward Witten Still Thinks String Theory 'on the Right Track'". scientificamerican.com. September 22, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- ^ Witten, Ed. "The 2014 Kyoto Prize Commemorative Lecture in Basic Sciences" (PDF). Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "Faculty » Ilana B. Witten". princeton.edu. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "UW Faculty » Daniela M. Witten". washington.edu. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ "Advisory Council". J Street. 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ISSN 0028-7504. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "Edward Witten for Americans for Peace Now". Americans for Peace Now. February 8, 2005. Retrieved April 5, 2024.

External links

- Faculty webpage

- Publications on ArXiv

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Edward Witten", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Edward Witten at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- A Physicist's Physicist Ponders the Nature of Reality, Interview with Nathalie Wolchover in Quanta Magazine, November 28, 2017