Fore River Shipyard

General Dynamics Corporation |

Fore River Shipyard was a

Most of the ships at the yard were built for the

The yard constructed several merchant marine ships, including Thomas W. Lawson, the largest pure sailing ship ever built, and SS Marine Dow-Chem, which was the first ship constructed to carry refrigerated chemicals. General Dynamics Quincy Shipbuilding Division, as it eventually came to be known, ended its career as a producer of various LNG tankers and merchant marine ships.

The yard would also construct a number of

According to one theory, the yard was the origin of the "

History

This section relies largely or entirely upon a single source. (August 2022) ) |

Origins

The shipyard traces its beginnings back to 1882, when

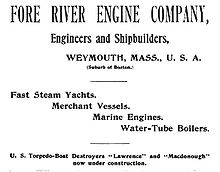

Fore River Engine Company

Following an order from Maine for a 50-horsepower engine, Thomas A. Watson and Frank O. Wellington decided to build boats, which came after realizing the profitability of the enterprise as the result of building their first ship, the Barnacle, which was fitted with local furnishings.[3] Watson later said of this decision:

It was a momentous decision for from it came one of the largest shipbuilding establishments in the country, if not in the world, that made Massachusetts again a shipbuilding center and afterwards played an important part in the World War.[3]

The success of this operation was further strengthened the fact that the shipyard was producing a quality engine, and it quickly gained a reputation along the eastern seaboard. Soon, a new engine-building facility was constructed, employing between twenty and thirty workers. Additionally, the Prouty Printing Press and Sims-Dudley dynamite gun, staple guns for shoes, and electric light accessories were produced by Fore River. In addition, the diversity of Fore River's products was due to the fact that Watson desired to employ as many friends as possible.[3]

The

The awarding of USS Des Moines (CL-17) was also beneficial for Fore River. Faced with the problem of not having a large enough area to build the cruiser, the contract was produced at the new Quincy yard. The Des Moines was launched in 1902 and commissioned in 1904, bringing with it some financial stability to the yard, as new revenues were quadruple those at the East Braintree location. During the construction of the new yard, old buildings were floated over to make up for the lack of buildings at the new location, and it was constructed with some of the largest shipbuilding equipment of the day.[3]

Fore River Ship and Engine Company

The building of the new yard created ample space for building new ships, which allowed for the building of USS New Jersey (BB-16) and USS Rhode Island (BB-17). The Navy did mandate that before they could receive the bids, they would have to incorporate, so the company was incorporated in New Jersey, with a capital of $6.5 million (equivalent to $229 million in today's dollars).[4] Immediately, Thomas A. Watson realized that the contract would be more costly than anticipated, but soon an order came in for the seven-masted Thomas W. Lawson. This was immediately followed by an order for the six-masted William L. Douglas, which was delivered in 1903.[3]

In 1902, Watson decided to build the

During this time, the yard struggled financially, as expenses from suppliers exceeded reimbursement from the Navy. As a result, Watson decided to sell some of his telephone stock and secured a loan. At this time, the yard was awarded with a contract for USS Vermont (BB-20), although this did not solve the company's troubles. Following a failed attempt by Watson to seek reimbursement from the Navy, he eventually resigned and was replaced by former Admiral Francis T. Bowles, as he was pleased by how Bowles ran the yard.[3]

In 1905, the yard gained a contract to build the Brown-Curtis steam turbine engine, which was considered to be too fast to be economical at the time. That same year, the Navy awarded a contract to build the Chester-class cruisers at the yard, two of which were supposed to be equipped with the Brown-Curtis turbine, but which later received new turbines.[3]

The

During this time, the yard built civilian ships, including

In 1906, USS New Jersey (BB-16) and USS Rhode Island (BB-17) were delivered by the yard, marking the yard's first battleships delivered. The completion of these two battleships and other ships at the yard coincided at a time when there were 2,500 people employed. In 1908, there were eighteen contracts employed at Fore River, which would not be met again until 1916. The yard also completed car floats for the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad during this time.[3]

Of note, Fore River fielded a soccer team from at least 1907 to around 1920–1921. This team, which played in local leagues, was part of one of the early soccer leagues in the United States.[7]

Another big development in the history of the yard was the receiving of the contract to build the

Rivadavia was built by Fore River, but they were contractually obligated to

The ship was laid down in 1910, but was finally delivered in 1914 after delays in construction due to a work backlog at the yard. It was because of this issue that Admiral Bowles suggested that the yard be sold to a larger corporation, as it would be able to better deal with the extra workload than the yard could on its own. The last ship laid down in the yard at the time was USS Nevada (BB-36), which occurred in 1912.[3]

In 1911, the yard was part of the case

Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation, Ltd.

In 1913,

The first year of the company's ownership brought little in terms of business. Two destroyers were ordered, three submarines were sublet in the yard, and no outside orders by private companies were received in this time. Furthermore, the

World War I

War brought opportunities for expansion for the yard. This meant the building of a steel mill and a sheet metal shop that contained one of the best molds in the country. The steel mill was capable of prefabricating 250 short tons (230 t) of steel a day. A 1,000-foot (300 m) building slip was also constructed, costing $500,000 (equivalent to $17.6 million in today's dollars).[4] The yard created a department that was dedicated to the welfare of its workers during this time, as well.[3]

1916 brought nineteen contracts to the yard, eight of which were for the

Entry of the United States into the war brought twenty-eight destroyer orders to the yard. Due to this sudden increase in production, the yard needed to expand. Soon, a suitable location was found on nearby

Combined with the Squantum yard, Fore River turned out 71 destroyers during the war, more than any other American yard. Besides the other Quincy yard, Bethlehem built the Fields Point Plant for boiler construction in nearby Providence, Rhode Island and the Black Rock Plant for turbines in Buffalo, New York. The yard constructed USS Mahan (DD-102) in 174 days. Not to be outdone, the Squantum yard built USS Reid (DD-292) in twenty-eight days, delivering it to the Navy seventeen days later. Such was the speed at which the yard produced ships that the Navy was forced to moor the ships at the Boston Navy Yard for lack of crews. The yard's speed allowed for the management to enter a bet with another Bethlehem plant, Union Iron Works, to see which plant would deliver more ships in a year. At the end of 1918, Fore River delivered eighteen ships to Union's six.[3]

Post-War and Great Depression

The end of World War I did not immediately affect the yard, as it was still producing ships from wartime orders. The only cancellations that occurred in the yard after the war were the cancellation of the Lexington-class battlecruiser USS Lexington (CC-1). This was offset by the construction of two cruisers, which were delivered in due time. Additionally, the yard finished building the multiple orders that it received for the S-class submarine, as well as orders for two other submarines.[3]

Between 1922 and 1925, the yard underwent a major expansion period, including the purchase of the

The post-war lull brought about new opportunities for the yard, as it converted or upgraded ships such as

The Great Depression brought little work to the yard, with the exception of the completion of USS Quincy (CA-39) and USS Vincennes (CA-44). USS Wasp (CV-7) was built from 1936 to 1940, in addition to a handful of destroyers. Employment in the yard dropped drastically during this time, from 4,900 in 1931 to 812 two years later.[3]

World War II

The Naval Act of 1938 brought increased shipbuilding to the yard, as it mandated a 20% increase in the strength of the nation's Navy.[17] This brought an expansion of business to the yard, with 17,000 employees working in December 1941 and 32,000 in 1943, including 1,200 women. Payroll reached $110 million (equivalent to $1.94 billion in today's dollars)[4] around this time, and contracts amounted to around $700 million (equivalent to $12.3 billion in today's dollars).[4][3]

The speed of construction at the yard increased, as the keel of USS Vincennes (CL-64) was laid immediately after USS Massachusetts (BB-59) was launched. The speed of the construction ran in line with the building of more ships. USS San Juan (CL-54) was cut up and relocated three times in order to accommodate the construction of other ships. Much like World War I, the yard expanded, and built the Bethlehem Hingham Shipyard in order to accommodate the increased construction demands. Sixteen ways were constructed on over 96 acres (39 ha; 0.150 sq mi), and 227 ships were produced with 23,500 workers.[3]

The yard produced USS Hancock (CV-19) in fourteen and a half months, and USS Pasadena (CL-65) in a record of sixteen and a half months. The yard built ninety-two vessels of eleven classes during the war, and earned the Army-Navy "E" Award for excellence of construction of vessels, which was awarded on 15 May 1942, with four stars being added during the course of the war. Additionally, the yard produced USS Lexington (CV-16), which was renamed from USS Cabot after the sinking of USS Lexington (CV-2) when yard workers petitioned for a renaming of the ship.[3]

During the war, the yard was possibly the origin of the popular expression "Kilroy was here."[18] Although it was not known originally where the phrase came from, the American Transit Association ran a contest trying to find the origin of the phrase in 1946. Welding inspector James J. Kilroy ended up sending his account in, and was deemed the winner. In an attempt to make sure that riveters would be prevented from defrauding the shipyard of their accurate workload, he scrawled the phrase in chalk on the ships that he was inspecting. Ships that the phrase was printed on included USS Massachusetts, USS Lexington, USS Baltimore (CA-68) and various troop carriers.[3]

While the shipyard was at its peak of operations during the war, it was not uncommon for German U boats to stalk ships leaving the yard and engage them once offshore.[19]

Post-war

After the war, the yard was faced with new opportunities. As the war greatly expanded the yard, the yard now had extra space. Thus, the Hingham yard was closed, and the yard diversified its interests. The yard constructed a 28-foot (8.5 m) blast furnace, a wind tunnel, draglines, and steel for an aqueduct of the Boston's Metropolitan District Commission, a transformer for Boston Edison, among other things. The yard was faced with inflation, increasing material costs, and demands for higher wages.[3]

The yard did continue to turn out war orders for the ships

During this time, work continued to decline for the yard, although the yard found work in contracts from the

The yard's slow work after the war was a symptom of having a glut of extra ships that were available for the

The yard began a new era when it was awarded construction of USS Long Beach (CGN-9), a nuclear guided-missile cruiser. Such was the amount of work involved in the building of the Long Beach that the yard had to decline building NS Savannah, the world's first nuclear-powered merchant ship. The yard entered into an expansion period during these years, replacing six pre-World War I sliding ways, which could now accommodate between three and six ships. Ships were built for the Greek shipping company Stavros Niarchos including a tanker with a capacity of 16.5 million US gallons (62 megalitres) of crude oil, named SS World Glory and SS World Beauty. The yard produced the nation's largest tanker, SS Princess Sophie, which was christened by Frederica of Hanover, Queen of Greece.[3] Fore River also branched out into radar tower construction in this time, constructing Texas Tower 2 in 1955 and Texas Tower 3 in 1956.[20]

The 1960s began with a five-month strike by workers over either wages and benefits (according to local newspapers), or unilateral work rules (according to the

1962 brought about the construction of SS Manhattan, which was the largest commercial vessel built in the United States at the time, and became the first ship to transit the Northwest Passage to the Alaska North Slope oil fields. The Bainbridge was launched in that year, but not without accusations from the government that Bethlehem overcharged the Navy, as the costs increased from almost $70.1 million (equivalent to $733 million in today's dollars)[4] in 1959 to a negotiated $87 million (equivalent to $876 million in today's dollars)[4] three years later, down from an estimate of $90 million (equivalent to $907 million in today's dollars)[4] before then, although there was a $5 million (equivalent to $50.4 million in today's dollars)[4] discrepancy in the yard. After the end of the strike mentioned above, the yard was accused by the government of overcharging for the first nuclear frigate, USS Bainbridge (CGN-25) and the Long Beach. The shipyard later made up for the losses of $139,000 (equivalent to $1.42 million in today's dollars)[4] by crediting on other contracts that were being offered.[3]

1963 brought an end of an era to the yard, as Bethlehem put the yard up for sale. Fifty years of Bethlehem ownership, which began when the yard was near financial ruin, came to an end as the yard was one of the most established yards in the world.[3]

General Dynamics Quincy Shipbuilding Division

In 1964, the yard was purchased by

The yard was soon awarded the contract for the reconfiguration of the

The addition of the

The addition of modular construction to the yard meant that it could build ships by assembling pre-fabricated units, a technique that was used at the Victory Destroyer Plant during World War I. During the end of 1971, the yard was faced with declining contracts, which created rumors that the yard was close to closing. The yard was in discussion to gain a $350 million (equivalent to $2.63 billion in today's dollars)[4] contract for six supertankers, which would carry 65 million US gallons (250 megalitres) of crude oil each. These tankers were supposed to be constructed with a forty-three percent subsidy from the federal government, which was granted. Eventually though, funding fell through, and construction did not proceed on the ships. Despite this, the yard modified USNS Hayes (T-AGOR-16), which was a $1.79 million (equivalent to $12.3 million in today's dollars)[4] contract, where the ship received new equipment. This contract provided one hundred jobs for the yard.[3]

The first attempt at government intervention for the yard came with Congressman James A. Burke aiming to stave off the imminent layoffs of two thousand workers. He attempted to get the yard awarded the contract for repairs to USS Puget Sound (AD-38). In a telegram to then-Secretary of Defense Elliot Richardson, he said that the closure of the Boston Navy Yard created a labor surplus. Unfortunately for the yard, the contract never panned out.[3]

Delivery of USS Kalamazoo (AOR-6) in 1973 meant that the only work at the yard consisted of the modification of the Hayes and construction of cylinders for submarines at Newport News Shipbuilding and Electric Boat, which helped to maintain work for about two hundred and eighty machine shop workers. Economic salvation came to the yard during the construction of LNG-41, which was calculated to bring 5,500 to 6,000 workers employment. Projected to begin in July 1973, the work was delayed until December due to delays in yard improvements. In the meantime, the Irving Sealion was repaired at the yard. The Esso Halifax, which struck an iceberg on the way to Resolute Bay in Nova Scotia was repaired in the yard during this time.[3]

The laying down of the LNG-41 occurred during the repair of USS West Milton (ARD-7), which was used to repair submarines at Naval Submarine Base New London. Congressman Burke was instrumental in securing this work, which kept the yard busy in 1974. That same year, a seventeen-week strike broke out, which created a situation where all work stopped and tanker work came to a halt. Eventually, the strike was resolved, but not before jeopardizing the future of the yard. After the settlement of the strike, USS Raleigh (LPD-1) was repaired at the yard in 1975, as General Dynamics had the lowest bid. In 1975, the yard had eight LNG contracts, which totaled $650 million (equivalent to $3.68 billion in today's dollars).[4][3] It was around this time that the Goliath crane was constructed, which was a 1,200 short tons (1,100 t) crane built for the construction of tankers. Until it was removed in 2008, it was the largest gantry crane in North America.[23]

The final construction project for the yard came in the form of construction of five

Redevelopment

Closure of the division initially led to dormancy at the yard. Some equipment was sold off while other parts of the yard were used for staging areas of the Boston Harbor cleanup project. Various plans were then offered at the time for use of the shipyard.[27]

During this period, a ship scrapping operation, operating under the name Fore River Shipyard and Iron Works existed at one end of the yard.[24] An initial purchase of five former Forrest Sherman-class destroyers was made, which included the USS Forrest Sherman (DD-931), USS Davis (DD-937), USS Manley (DD-940), USS Du Pont (DD-941), USS Bigelow (DD-942) and USS Blandy (DD-943). Of these, Du Pont was the only one that was successfully scrapped, as the company concluded that the costs of scrapping the other ships would exceed their scrap value. The company later sought bankruptcy protection in 1994, and the remaining ships were sold to other scrap dealers by the Massachusetts Bankruptcy Court.[28]

In 1992, a group of volunteers came up with the idea of purchasing a ship built at the shipyard and relocating it to a new museum that would celebrate the history of the yard. In 1993, the United States Naval Shipbuilding Museum was established by the Massachusetts General Court with the aim to, "acquire, refurbish and maintain United States naval ships and the adjacent physical complex in order that it will [serve] as a major attraction for local citizens and tourists."[29] Initially, plans called for the purchase of USS Lexington (CV-16), but the museum ended up getting USS Salem (CA-139), the last all-gun heavy cruiser ever built, returned to the Quincy yard after negotiations with the Naval Sea Systems Command.[30] On 30 October 1994 Salem returned to Quincy to be permanently docked where she was built nearly five decades before.[31][32] In May 2014, however, it was announced that the Salem would be moved to East Boston after the pier the ship was berthed and closed the previous September due to safety reasons.[33][34] The move never took place, and the ship remains open as a museum at Fore River.

In 1995, Sotirious Emmanouil purchased the former yard and promised to restore shipbuilding to the yard, through his company Massachusetts Heavy Industries. The company cleaned up much of the yard and built a handful of buildings after securing a $55 million (equivalent to $110 million in today's dollars)[4] loan, but was unable to secure any contracts and became mired in disputes. The company eventually defaulted on its loans and the property was seized by the United States Maritime Administration in 2000, with its assets being auctioned off a few years later.[35]

Daniel J Quirk, a local auto dealer, bought the property in 2004 for use as a motor vehicle storage and distribution facility. Before the

On 14 August 2008, ironworker Robert Harvey was killed when a portion of the Goliath crane collapsed during dismantlement.[36] Work on the crane's removal was halted for two months while local and federal officials investigated the accident, but the work later resumed and was completed in early 2009.[37] As a result of their investigation, on 13 January 2009 the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration imposed fines totalling $68,000 (equivalent to $96,230 in today's dollars).[4][38] A barge carrying the crane was christened USS Harvey in honor of the fallen worker and left the shipyard on 7 March 2009 en route to Romania.[39][40]

The August 2008 fatal incident was preceded by two other deaths involving demolition of the main gantry crane at the shipyard on 26 January 2005.[41] The earlier incident resulted in an OSHA ruling against Testa Corporation of Lynnfield, Massachusetts, including a proposed $60,400 (equivalent to $94,228 in today's dollars)[4] fine.[42] Following the 2005 collapse, violations involving improper cleanup and removal of asbestos found in debris left by the accident resulted in a $75,000 (equivalent to $113,354 in today's dollars)[4] penalty imposed against Testa by the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection.[43]

The former shipyard served as a port for commuter boats to

Although shipbuilding operations ceased in 1986, the name of the yard continues to be used, and the location is still referred to as Fore River Shipyard.[46]

Appearance in film

Fore River Shipyard has also appeared in multiple films since it was closed. The climactic shootout from the 2006 film

World War II Slipways

| Shipway | Width | Length | Date | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 28 feet (8.5 m) | 130 feet (40 m) | 1941 | [50] |

| 28 feet (8.5 m) | 130 feet (40 m) | |||

| 2 | 40 feet (12 m) | 375 feet (114 m) | 1941 | |

| 3 | 40 feet (12 m) | 375 feet (114 m) | 1941 | |

| 4 | 95 feet (29 m) | 550 feet (170 m) | 1920 | |

| 5 | 90 feet (27 m) | 700 feet (210 m) | 1915-30 | |

| 6 | 76 feet (23 m) | 675 feet (206 m) | 1915-31 | |

| 7 | 84 feet (26 m) | 675 feet (206 m) | 1902-42 | |

| 8 | 84 feet (26 m) | 675 feet (206 m) | 1901-42 | |

| 9 | 82 feet (25 m) | 650 feet (200 m) | 1916-30 | |

| 10 | 110 feet (34 m) | 875 feet (267 m) | 1917-30 | |

| 11 | 150 feet (46 m) | 1,000 feet (300 m) | 1941 | |

| 12 | 150 feet (46 m) | 1,000 feet (300 m) | 1941 |

Ships constructed at Fore River

During the almost one hundred years that the yard was operational, it produced hundreds of ships, submarines, and personal sailing vessels. Among these orders were the civilian ships the Barnacle and the multiple-masted schooners the Thomas W. Lawson and William L. Douglas. The yard produced military contracts, including USS Lawrence (DD-8) and USS Macdonough (DD-9). Submarines were constructed, including USS Octopus (SS-9) for the United States Navy, and others for both the Imperial Japanese Navy and the Royal Navy.[3]

As the yard was expanded over the years, it built battleships such as USS New Jersey (BB-16), USS Nevada (BB-36), and the preserved USS Massachusetts (BB-59), itself moored in Battleship Cove. Other naval ships include the preserved heavy cruiser USS Salem (CA-139) (as part of the United States Naval Shipbuilding Museum adjacent to the shipyard), USS Northampton (CLC-1), and USS Long Beach (CGN-9). The yard constructed multiple aircraft carriers, including the conversion of the battlecruiser USS Lexington CC-1''s hull into USS Lexington (CV-2), USS Lexington (CV-16), USS Bunker Hill (CV-17), and USS Philippine Sea (CV-47).[3]

After the war, the yard found itself faced with changing realities, and increasingly relied on merchant marine ships, including

Notes

Endnotes

- ^ "General Dynamics announces closing of its Quincy shipyard". UPI. 25 July 1985. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ "S.S. Independence and S.S. Constitution; Bethlehem-Built". digital.wolfsonian.org. Archived from the original on 2021-01-22. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au Rines, Lawrence S.; Sarcone, Anthony F. "A History of Shipbuilding at Fore River". Thomas Crane Public Library. Archived from the original on 7 September 2008. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "The Fore River Railroad". Massachusetts Water Resources Authority. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- ^ Dell'Apa, Frank (28 September 2005). "A Steelworker Forged History". Boston.com. The Boston Globe. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ a b Livermore, "Battleship Diplomacy," 38.

- ^ a b "Argentine Navy; Dreadnought Orders," Evening Post, 23 March 1910, 4.

- ^ Alger, "Professional Notes," 595.

- ^ Scheina, Latin America, 83.

- ^ Livermore, "Battleship Diplomacy," 39.

- ^ "FORE RIVER SHIPBUILDING CO. v. HAGG, 219 U.S. 175 (1911) 219 U.S. 175". FindLaw. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ISBN 978-0810856349. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ^ Shipping: The Magazine of Marine Transportation, Construction, Equipment, and Supplies. New York City, New York: Shipping Publishing Company, Inc. December 1922. p. 42. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Rogers, J. David. "Development of the World's Fastest Battleships" (PDF). Missouri University of Science and Technology. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- OCLC 45532422. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ^ ROSE, JIM. "Recalling Nazi spies off the New England coast, and a mystery on a Scituate beach".

- ^ "The Construction". Archived from the original on 2 August 2011. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ "Range Instrumentation Ship Photo Index". www.navsource.org.

- ^ "Fore River Shipyard Production Record". www.hazegray.org. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Jette, Julie (5 January 2008). "Farewell, GOLIATH: The skyline is about to change". The Patriot Ledger. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 24, 2008.

- ^ a b "The MPS Program at Quincy Shipbuilding". Hazegray.org. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ^ Langner, Paul (18 May 1986). "Ship's Christening Signals Shipyard's Death". The Boston Globe. pp. Metro Page 29.

- ^ "Workers Brace for Closing of Quincy Shipyard". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. 27 May 1986. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ Radin, Charles A. (30 December 1996). "Water Board Seeking Part of Quincy Yard". The Boston Globe. pp. Metro Page 1.

- ^ Kennedy, John H. (21 January 1994). "Quincy shipyard firm seeks Chap. 11". The Boston Globe.

- ^ "State Library of Massachusetts Archives, 1993". State Library of Massachusetts Archives. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Reid, Alexander (17 July 1994). "Surplus Warship Scheduled to Arrive in City in August". The Boston Globe. pp. South Weekly Section Page 1.

- ^ "Rescued from Navy Mothballs, USS Salem is Returning Home". The Boston Globe. 29 October 1994. pp. Metro Page 17.

- ^ Jackson, Scott (May 8, 2014). "USS Salem Bound For East Boston". The Quincy Sun. Archived from the original on May 13, 2014. Retrieved May 10, 2014.

- ^ a b Ronan, Patrick (23 March 2015). "USS Salem to reopen in Quincy before move to Boston". Wicked Local Quincy. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ a b Preer, Robert (21 May 2006). "From shipyard to village". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ^ Abel, David; Sweeney, Emily (15 August 2008). "Crane collapse kills ironworker". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ "Removal of shipyard crane in Quincy expected to be finished by Christmas". The Patriot Ledger. 7 November 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- Occupational Safety & Health Administration. Retrieved 13 January 2009.

- ^ Aicardi, Robert (27 February 2009). "Departing Goliath crane renamed USS Harvey". Braintree Forum. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ^ Lotan, Gal Tziperman (7 March 2009). "Landmark Goliath crane ships out for new home in Romania". The Patriot Ledger. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ^ Ebbert, Stephanie (27 January 2005). "Two die in Braintree collapse". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- Occupational Safety & Health Administration. Archived from the originalon 24 December 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ "2006 Enforcement Actions". Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection. Retrieved 20 May 2009.

- ^ Jackson, Scott. "Council Calls For Restoration Of Commuter Ferry Service". The Quincy Sun. Archived from the original on September 14, 2014. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ Trufant, Jessica; Schiavone, Christian (4 August 2014). "Mechanical problem to delay Fore River Bridge completion one year". The Patriot Ledger. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ^ "Fore River Shipyard". Fore River Shipyard Redevelopment Project. Archived from the original on 16 June 2010. Retrieved 4 August 2009.

- ^ a b "Former Fore River Shipyard gets a big role in "The Company Men"". The Patriot Ledger. 27 January 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ "Ben Affleck filming 'The Company Men' in Roxbury". Loaded Guns. 13 April 2009. Archived from the original on 23 April 2009. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ Wright, Emily (7 August 2014). "Report: Casey Affleck to Join 'The Finest Hours' Cast". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ "General Dynamics Corporation Shipyard: Addendum" (PDF).

References

- Livermore, Seward W. "Battleship Diplomacy in South America: 1905–1925." The Journal of Modern History 16, no. 1 (1944): 31–44. OCLC 62219150.

- Scheina, Robert L. "Argentina." In Gardiner and Gray, Conway's, 400–403.

- ———. "Brazil." In Gardiner and Gray, Conway's, 403–407.

- ———. Latin America: A Naval History 1810–1987. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1987. OCLC 15696006.

Further reading

- Tillman, Barrett (2005). Clash of the Carriers. New American Library. ISBN 978-0-451-21670-0.

- Palmer, David (1998). Organizing the Shipyards: Union Strategy in Three Northeast Ports, 1933–1945. ISBN 978-0-8014-2734-3.

- Blair, Clay Jr. (1975). Silent Victory, Volume 2. J. B. Lippincott Company. ISBN 978-1-55750-217-9.

- ISBN 978-0-87021-646-6.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1968). U.S. Warships of World War II. Doubleday and Company. ISBN 978-0-87021-773-9.

External links

- GlobalSecurity.org website Page focusing on facts surrounding Fore River Ship and Engine Company/General Dynamics Shipbuilding Division in Quincy, MA

- Historic American Engineering Recorddocumentation, filed under 97 East Howard Street, Quincy, Norfolk County, MA:

- HAER No. MA-26, "General Dynamics Corporation Shipyard", 6 photos, 25 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- HAER No. MA-26-A, "General Dynamics Corporation Shipyard, Joiner & Sheet Metal Shops", 16 photos, 7 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- HAER No. MA-26-B, "General Dynamics Corporation Shipyard, Apprentice School", 11 photos, 7 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- HAER No. MA-26-C, "General Dynamics Corporation Shipyard, Outfitting Pier No. 2", 7 photos, 6 data pages, 12 photo caption pages

- HAER No. MA-26-D, "General Dynamics Corporation Shipyard, Outfitting Pier No. 3", 4 photos, 6 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- HAER No. MA-26-E, "General Dynamics Corporation Shipyard, XYZ Crane & Towers", 11 photos, 6 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- HAER No. MA-26-F, "General Dynamics Corporation Shipyard, Dravo Cranes", 12 photos, 6 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- HAER No. MA-26-G, "General Dynamics Corporation Shipyard, McMyler Crane", 16 photos, 7 data pages, 3 photo caption pages

- HAER No. MA-26-H, "General Dynamics Corporation Shipyard, Wellman-Seaver Crane", 10 photos, 7 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- HAER No. MA-26-I, "General Dynamics Corporation Shipyard, American Revolver Crane", 6 photos, 6 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- Images of the yard

- Images of ships built at the yard

- Pictures of the yard, circa early 1900s