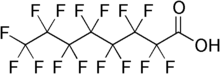

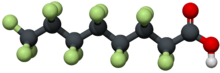

Perfluorooctanoic acid

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Pentadecafluorooctanoic acid | |

| Other names

Perfluorooctanoic acid, PFOA, C8, Perfluorooctanoate, PFO, Perfluorocaprylic acid, C8-PFCA, FC-143, F-n-octanoic acid

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (

JSmol ) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

ECHA InfoCard

|

100.005.817 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

RTECS number

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C8HF15O2 | |

| Molar mass | 414.07 g/mol |

| Appearance | White solid |

| Density | 1.8 g/cm3[1] |

| Melting point | 40 to 50 °C (104 to 122 °F; 313 to 323 K)[1] |

| Boiling point | 189 to 192 °C (372 to 378 °F; 462 to 465 K)[1] |

| Soluble, 9.5 g/L (PFO)[2] | |

| Solubility in other solvents | Polar organic solvents |

| Acidity (pKa) | ~0[3][4][5] |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

Strong acid, known carcinogen, persistent organic pollutant |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H302, H318, H332, H351, H360, H362, H372 | |

| P201, P202, P260, P261, P263, P264, P270, P271, P280, P281, P301+P312, P304+P312, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P308+P313, P310, P312, P314, P330, P405, P501 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | [1] |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds

|

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA;

The

PFOA is used in several industrial applications, including carpeting, upholstery, apparel, floor wax, textiles, fire fighting foam and sealants. PFOA serves as a surfactant in the

The primary manufacturer of perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), the 3M Company (known as Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company from 1902 to 2002), began a production phase-out in 2002 in response to concerns expressed by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).[13]: 2 Eight other companies agreed to gradually phase out the manufacturing of the chemical by 2015.[13]: 3

By 2014, EPA had listed PFOA and perfluorooctanesulfonates (

PFOA and PFOS are extremely persistent in the environment and resistant to typical environmental degradation processes. [They] are widely distributed across the higher trophic levels and are found in soil, air and groundwater at sites across the United States. The toxicity, mobility and bioaccumulation potential of PFOS and PFOA pose potential adverse effects for the environment and human health.[13]: 1

History

3M (then the Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company) began producing PFOA by

In 1968,

In 1999, EPA ordered companies to examine the effects of perfluorinated chemicals after receiving data on the global distribution and toxicity of PFOS.[20] For these reasons, and EPA pressure,[21] in May 2000, 3M announced the phaseout of the production of PFOA, PFOS, and PFOS-related products—the company's best-selling repellent.[22] 3M stated that they would have made the same decision regardless of EPA pressure.[23]

Because of the 3M phaseout, in 2002, DuPont built its own plant in Fayetteville, North Carolina, to manufacture the chemical.[24] The chemical has received attention due to litigation from the PFOA-contaminated community around DuPont's Washington Works facility in Washington, West Virginia, along with EPA focus. In 2004, ChemRisk—an "industry risk assessor" that had been contracted by Dupont, reported that over 1.7 million pounds of C8 had been "dumped, poured and released" into the environment from Dupont's Parkersburg, West Virginia-based Washington Works plant between 1951 and 2003.[25]

Research on PFOA has demonstrated ubiquity, animal-based toxicity, and some associations with human health parameters and potential health effects. Additionally, advances in

Robert Bilott investigation

In the Autumn of 2000, lawyer Robert Bilott, a partner at Taft Stettinius & Hollister, won a court order forcing DuPont to share all documentation related to PFOA. This included 110,000 files, consisting of confidential studies and reports conducted by DuPont scientists over decades. By 1993, DuPont understood that "PFOA caused cancerous testicular, pancreatic and liver tumors in lab animals" and the company began to investigate alternatives. However, because products manufactured with PFOA were such an integral part of DuPont's earnings, $1 billion in annual profit, they chose to continue using PFOA.[14] Bilott learned that both "3M and DuPont had been conducting secret medical studies on PFOA for more than four decades", and by 1961 DuPont was aware of hepatomegaly in mice fed with PFOA.[14][29][30]

Bilott exposed how DuPont had been knowingly polluting water with PFOAs in Parkersburg, West Virginia, since the 1980s.[14] In the 1980s and 1990s, researchers investigated the toxicity of PFOA.[30]

For his work in the exposure of the contamination, lawyer Robert Bilott has received several awards including

Synthesis

PFOA has two main synthesis routes,

PFOA is also synthesized by the

- CF3CF2I + F2C=CF2 → CF3CF2CF2CF2I

- CF3(CF2)3I + F2C=CF2 → CF3(CF2)5I

- CF3(CF2)5I + F2C=CF2 → CF3(CF2)7I

The product is

Applications

PFOA has widespread applications. In 1976, PFOA was reported as a water and oil repellent "in fabrics and leather and in the production of floor waxes and

As a

In a 2009 EPA study of 116 products, purchased between March 2007 and May 2008 and found to contain at least 0.01% fluorine by weight, the concentrations of PFOA were determined.

| Product | Range, ng/g |

|---|---|

| Pre-treated carpeting | ND (<1.5) to 462 |

| Carpet-care liquids | 19 to 6750 |

| Treated apparel |

5.4 to 161 |

| Treated upholstery | 0.6 to 293 |

| Treated home textiles | 3.8 to 438 |

| Treated non-woven medical garments | 46 to 369 |

| Industrial floor wax and wax removers | 7.5 to 44.8 |

| Stone, tile, and wood sealants | 477 to 3720 |

Membranes for apparel |

0.1 to 2.5 ng/cm2 |

| Food contact paper | ND (<1.5) to 4640 |

| Dental floss/tape | ND (<1.5) to 96.7 |

| Thread sealant tape | ND (<1.5) to 3490 |

PTFE cookware |

ND (<1.5) to 4.3 |

Global occurrence and sources

PFOA contaminates every

However, wildlife has much less PFOA than humans, unlike

Most industrialized nations have average PFOA

Industrial sources

PFOA is released directly from industrial sites. For example, the estimate for the DuPont Washington Works facility is a total PFOA emissions of 80,000 pounds (lbs) in 2000 and 1,700 pounds in 2004.[15] A 2006 study, with two of four authors being DuPont employees, estimated about 80% of historical perfluorocarboxylate emissions were released to the environment from fluoropolymer manufacture and use.[2] PFOA can be measured in water from industrial sites other than fluorochemical plants. PFOA has also been detected in emissions from the carpet industry,[67] paper[68] and electronics industries.[69] The most important emission sources are carpet and textile protection products, as well as fire-fighting foams.[70]

Precursors

PFOA can form as a breakdown product from a variety of precursor molecules. In fact, the main products of the fluorotelomer industry, fluorotelomer-based polymers, have been shown to degrade to form PFOA and related compounds, with half-lives of decades, both biotically

A majority of

Sources to people

People who lived in the PFOA-contaminated area around DuPont's Washington Works facility were found to have higher levels of PFOA in their blood from drinking water. The highest PFOA levels in drinking water were found in the Little Hocking water system, with an average concentration of 3.55 parts per billion during 2002–2005.[15] Individuals who drank more tap water, ate locally grown fruits and vegetables, or ate local meat, were all associated with having higher PFOA levels. Residents who used water carbon filter systems had lower PFOA levels.

Food contact surfaces

PFOA is also formed as an unintended byproduct in the production of

In 2008 as news stories began to raise concerns about PFOA in microwaved popcorn, Dan Turner, DuPont's global public relations chief, said, "I serve microwave popcorn to my three-year-old." Five years later, journalist Peter Laufer wrote to Turner to ask if his child was still eating microwave popcorn. "I am not going to comment on such a personal inquiry", Turner replied.[90][91]

Fluorotelomer coatings are used in fast food wrappers, candy wrappers, and pizza box liners.[92] PAPS, a type of paper fluorotelomer coating, and PFOA precursor, is also used in food contact papers.[73]

Despite DuPont's asserting that "cookware coated with DuPont Teflon non-stick coatings does not contain PFOA",

Potential path: sludge to food

PFOA and

Household dust

PFOA is frequently found in household dust, making it an important exposure route for adults, but more substantially, children. Children have higher exposures to PFOA through dust compared to adults.[102] Hand-to-mouth contact and proximity to high concentrations of dust make them more susceptible to ingestion, and increases PFOA exposure.[103] One study showed significant positive associations were recognized between dust ingestion and PFOA serum concentrations.[102] However, an alternate study found exposure due to dust ingestion was associated with minimal risk.[104]

Regulatory status

Drinking water and products

In the United States there are no federal drinking water standards for PFOA or PFOS as of early 2021. EPA began requiring public water systems to monitor for PFOA and PFOS in 2012,[105] and published drinking water health advisories, which are non-regulatory technical documents, in 2016. The lifetime health advisories and health effects support documents assist federal, state, tribal, and local officials and managers of drinking water systems in protecting public health when these chemicals are present in drinking water. The levels of PFOS and PFOA concentrations under which adverse health effects are not anticipated to occur over a lifetime of exposure are 0.07 ppb (70 ppt).[106] In March 2021 EPA announced that it would develop a National Primary Drinking Water Regulation for these contaminants.[107]

The

In 2018 the

Using information gained through a

The new ATSDR analysis derives provisional Minimal Risk Levels (MRLs) of 3x10−6 mg/kg/day for PFOA and 2x10−6 mg/kg/day for PFOS during intermediate exposure.[113] The European Food Safety Authority opinion sets a provisional tolerable weekly intake (TWI) of 6 x10−6 mg/kg body weight per week for PFOA.[114]

California and food packaging

An attempt to regulate PFOA in food packaging occurred in the US state of California in 2008. A bill, sponsored by State Senator

Fluorotelomers

Fluorotelomer-based products have been shown to degrade to PFOA over periods of decades;[71][72] these studies could lead EPA to require DuPont and others to reformulate products with a value over $1 billion.[118]

Health effects

Toxicology

PFOA is a possible

PFOA has been described as a member of a group of "classic non-genotoxic carcinogens".

An additional study has shown PFOA to be developmentally toxic, hepatotoxic, immunotoxic, and to have negative effects of thyroid hormone production.

Human data

PFOA is resistant to degradation by natural processes such as

In animals, PFOA is mainly present in the

The levels of PFOA exposure in humans vary widely. While an average American might have 3 or 4

Consumers

Single

Other impacts on exposure in utero

PFOA exposure on thyroid function has also been a topic of concern, and has found to negatively impact thyroid stimulating hormone even at low levels when exposed during fetal development.[141] PFOA is also shown to have obesogenic effects, and an experimental study found a positive correlation to low-dose prenatal exposure of PFOA and prevalence of overweight and high waist circumference in females at age 20.[142] A correlation between in utero PFOA exposure and mental performance has yet to be established, as many studies have resulted in insignificant results. For example, a study conducted near Parkersburg, West Virginia did not find a significant association between in utero PFOA exposure and performance of math skills or reading performance in children ages 6 to 12 living in the PFOA-contaminated water district.[143] Based on a cohort study conducted in the Mid-Ohio Valley, no clear association was found between prenatal exposure to PFOA and birth defects, although a possible association with brain defects was observed and requires further research and assessment.[144]

Extrapolated epidemiological data suggests a slight association between PFOA exposure and low birth weight.[145] This was consistent based on blood levels of PFOA metabolites regardless of the geographic residence of subjects.[145] Generally, the findings among human fetuses exposed to the chemical were considerably less drastic than what was seen in mice studies.[145] Because of this, studies linking exposure to low birth weight can be considered inconclusive.[145] PFOA exposure in the Danish general population was not associated with an increased risk of prostate, bladder, pancreatic, or liver cancer.[146] Maternal PFOA levels were not associated with an offspring's increased risk of hospitalization due to infectious diseases,[147] behavioral and motor coordination problems,[148] or delays in reaching developmental milestones.[149]

Employees and DuPont exposed community

In 2010, the three members of the C8 Science Panel

Facial birth defects, an effect observed in rat offspring, occurred with the children of two out of seven female DuPont employees from the Washington Works facility from 1979 to 1981.[30][155] Bucky Bailey is one of the affected individuals; DuPont, however, does not accept any liability from the toxicity of PFOA.[156] While 3M sent DuPont results from a study that showed birth defects to rats administered PFOA and DuPont moved the women out of the Teflon production unit,[30] subsequent animal testing led DuPont to conclude there was no reproductive risk to women, and they were returned to the production unit.[157] However, data released in March 2009 on the community around DuPont's Washington Works plant showed "a modest, imprecise indication of an elevation in risk ... above the 90th percentile ... based on 12 cases in the uppermost category", which was deemed "suggestive of a possible relationship" between PFOA exposure and birth defects.[158][159]

Legal actions

International action: Stockholm Convention

PFOA was proposed for listing under the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants in 2015, and on May 10, 2019, PFOA, its salts, and PFOA-related compounds were added to Annex A of the Stockholm Convention by the Conference of the Parties.[160] Several hundred salts and precursors of PFOA fall within the scope of the restriction.[161][162] A few specific exemptions remained. Among them is a time-bound exemption for PFOA in fire-fighting foam.

Industry and legal actions

DuPont has used PFOA for over 50 years at its Washington Works plant. Area residents sued DuPont in August 2001 and claimed DuPont released PFOA in excess of their community guideline of 1 part per billion resulting in lower property values and increased risk of illness.[30] The class was certified by Wood Circuit Court Judge George W. Hill.[163] As part of the settlement, DuPont has paid for blood tests and health surveys of residents believed to be affected.[164] Participants numbered 69,030 in the study, which was reviewed by three epidemiologists—the C8 Science Panel—to determine if any health effects are the likely result of exposure.

On December 13, 2005, DuPont announced a settlement with the EPA in which DuPont would pay US$10.25 million in fines and an additional US$6.25 million for two supplemental environmental projects without any admission of liability.[165]

On September 30, 2008, Chief Judge Joseph R. Goodwin of the United States District Court for the Southern District of West Virginia denied the certification of a class of Parkersburg residents exposed to PFOA from DuPont's facility because they did not "show the common individual injuries needed to certify a class action".[166] On September 28, 2009, Judge Goodwin dismissed the claims of those residents except for medical monitoring.[163][167] By 2015, more than three thousand plaintiffs have filed personal-injury lawsuits against DuPont.[14] In 2017, DuPont reached a $670.7 million cash settlement[168] related to 3,550 personal injury lawsuits tied to PFOA contamination of drinking water in the Parkersburg area. Chemours, which was spun off from DuPont in 2015, agreed to pay half the settlement. Both companies denied any wrongdoing.

U.S. federal government actions

In 2002, a panel of toxicologists, including several from EPA, proposed a level of 150 ppb for drinking water in the PFOA contaminated area around DuPont's Washington Works plant. This initially proposed level was much higher than any known environmental concentration[47] and was over 2,000 times the level EPA eventually settled on for the drinking water health advisory.

In July 2004, EPA filed a suit against DuPont alleging "widespread contamination" of PFOA near the Parkersburg, West Virginia plant "at levels exceeding the company's community exposure guidelines;" the suit also alleged that "DuPont had—over a 20 year period—repeatedly failed to submit information on adverse effects (in particular, information on liver enzyme alterations and birth defects in offspring of female Parkersburg workers)."[30]

In October 2005, a USFDA study was published revealing PFOA and PFOA precursor chemicals in food contact and

On January 25, 2006, EPA announced a voluntary program with several chemical companies to reduce PFOA and PFOA precursor emissions by the year 2015.[169]

On February 15, 2005, EPA's Science Advisory Board (SAB) voted to recommended that PFOA should be considered a "likely human carcinogen".[170]

On May 26, 2006, EPA's SAB addressed a letter to Administrator Stephen L. Johnson. Three-quarters of advisers thought the stronger "likely to be carcinogenic" descriptor was warranted, in opposition to EPA's own PFOA hazard descriptor of "suggestive evidence of carcinogenicity, but not sufficient to assess human carcinogenic potential".[171]

On November 21, 2006, EPA ordered DuPont to offer alternative drinking water or treatment for public or private water users living near DuPont's Washington Works plant in West Virginia (and in Ohio), if the level of PFOA detected in drinking water is equal to or greater than 0.5 parts per billion. This measure sharply lowered the previous action level of 150 parts per billion that was established in March 2002.[172]

According to a May 23, 2007,

In November 2007, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published data on PFOA concentrations comparing 1999–2000 vs. 2003–2004 NHANES samples.[65]

On January 15, 2009, EPA set a provisional health advisory level of 0.4 ppb in drinking water.[100]

On May 19, 2016, EPA lowered the drinking water health advisory level to 0.07 ppb for PFOA and PFOS.

In October 2021 the EPA proposed to designate PFOA and PFOS as hazardous substances in its PFAS Strategic Roadmap.[175][176] In September 2022 the EPA proposed to designate as hazardous substances under the Superfund Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA).

In March 2023 EPA published a proposed rule for public water systems, covering PFOA and five other PFAS chemicals.[177][178]

U.S. state government actions

New Jersey

In 2007 the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) announced that it found PFOA at "elevated levels in the system's drinking water near DuPont's massive Chambers Works chemical plant".[179]

In 2018 the state published a drinking water standard for PFNA. Public water systems in New Jersey are required to meet a maximum contaminant level (MCL) standard of 13 ppt.[109][180]

In 2019 New Jersey filed lawsuits against the owners of two plants that had manufactured PFASs (the Chambers Works and the Parlin plant in Sayreville), and two plants that were cited for water pollution from other chemicals. The companies cited are DuPont, Chemours and 3M.[181]

In 2020 the NJDEP set a PFOA standard at 14 ppt and a PFOS standard at 13 ppt.[108]

New York

In 2018 the New York State Department of Health adopted drinking water standards of 10 ppt for PFOA and 10 ppt for PFOS, effective in 2019 after a public comment period.[110]

Michigan

In November 2017, the Michigan PFAS Action Response Team (MPART) was created to address growing pollution concerns after multiple sites contaminated by PFAS were identified. MPART is a multi-agency team tasked with investigating PFAS contamination sites and sources in the state, protecting drinking water, enhancing interagency communication and keeping the public informed.[182]

In January 2018, Michigan established a legally enforceable groundwater cleanup level of 70 ppt for both PFOA and PFOS. Two science advisory committees were also created and joined MPART to "coordinate and review medical and environmental health, PFAS science and develop evidence-based recommendations".[183]

In August 2020, the Michigan Department Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy adopted stricter drinking water standards in the form of MCLs, lowering acceptable levels from the 2018 enforceable groundwater cleanup levels of 70 ppt to 8 ppt for PFOA and 16 ppt for PFOS and adding MCLs for 5 previously unregulated PFAS compounds PFNA, PFHxA, PFHxS, PFBS, and HFPO-DA.[184][185]

Minnesota

In 2007, the Minnesota Department of Health lowered its Health Based Value for PFOA in drinking water from 1.0 ppb to 0.5 ppb,[186] where "the sources are landfilled industrial wastes from a 3M manufacturing plant".[179]

European action

PFOA contaminated waste was incorporated into soil improver and spread on agricultural land in Germany, leading to PFOA drinking water contamination of up to 0.519

In the Netherlands, after questions by members of Parliament, the minister of Environment ordered a study into the potential exposure to PFOA of people living in the vicinity of the DuPont factory in Dordrecht. The report was published in March 2016 and concluded that "prior to 2002 residents were exposed to levels of PFOA at which health effects could not be ruled out".[189] As a result of this, the government commissioned several further studies, including blood tests and measurements in drinking water.

PFOA was identified as a

The EU adopted the listing of PFOA in Annex A of the Stockholm Convention with Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2020/784 of 8 April 2020 and introduced a limit value of 0,025 mg/kg for PFOA including its salts, and at 1 mg/kg for the individual PFOA-related compounds or a combination of those compounds.[191] They also included some specific exemptions. Among them is a time-bound exemption for PFOA in fire-fighting foam.

Australian action

On August 10, 2016, Australian litigation funder IMF Bentham announced an agreement to fund a class action led by the law firm Gadens against the Australian Department of Defence for economic losses to homeowners, fishers, and farmers resulting from the use of aqueous film forming foam (containing PFOA) at RAAF Base Williamtown.[192]

See also

- Timeline of events related to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)

References

- ^ a b c d Record of Perfluorooctanoic acid in the GESTIS Substance Database of the Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, accessed on 5 November 2008.

- ^ PMID 16433330.

- PMID 18284146.

- PMID 19569653.

- .

- ^ PMID 14703372.

- S2CID 265571186.

- ^ a b "Per- and Polyfluorinated Substances (PFAS) Factsheet | National Biomonitoring Program | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2022-05-03. Retrieved 2024-04-12.

- ^ "Per- and Polyfluorinated Substances (PFAS) Factsheet | National Biomonitoring Program | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2022-05-03. Retrieved 2024-04-12.

- ^ "Emerging chemical risks in Europe — 'PFAS' — European Environment Agency". www.eea.europa.eu. Retrieved 2024-04-12.

- PMID 21866930.

- ^ a b Salager JL (2002). FIRP Booklet # 300-A: Surfactants-Types and Uses (PDF). Universidad de los Andes Laboratory of Formulation, Interfaces Rheology, and Processes. p. 44. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-31. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

- ^ a b c Emerging Contaminants Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) (Report). EPA. March 2014. 505-F-14-001. Fact sheet.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rich, Nathaniel (6 January 2016). "The Lawyer Who Became DuPont's Worst Nightmare". New York Times. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ PMID 16902368.

- ^ "Perfluorooctanoic acid". National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- ^ S2CID 8873920.

- PMID 11999053.

- ^ PMID 15236955.

- ^ Ullah A (October 2006). "The Fluorochemical Dilemma: What the PFOS/PFOA fuss is all about" (PDF). Cleaning & Restoration. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ^ Lee J8 (15 April 2003). "E.P.A. Orders Companies to Examine Effects of Chemicals". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 May 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "3M United States: PFOS PFOA: What is 3M Doing?". 3M Company. Archived from the original on 2014-12-10. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

- ^ Weber J (2000-06-05). "3M's Big Cleanup – Why it decided to pull the plug on its best-selling stain repellent". Business Week (3684): 96.

- ^ a b Ward K Jr (7 November 2008). "DuPont finds high C8 in Chinese workers". The Charleston Gazette. Archived from the original on 2009-02-24. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ Mordock J (April 1, 2016). "Taking on DuPont: Illnesses, deaths blamed on pollution from W. Va. plant". Delaware Online. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ "GORE completes elimination of PFOA from raw material of its functional fabrics: GORE-TEX Products Newsroom". Gore Fabrics. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ US EPA O (2016-05-10). "Fact Sheet: 2010/2015 PFOA Stewardship Program". US EPA. Retrieved 2019-10-21.

- PMID 28962433.

- ^ Arneson GJ (November 1961). Toxicity of Teflon Dispersing Agents (PDF). DuPont, Polychemicals Department, Research & Development Division, Experimental Station. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-10-02. Retrieved 2008-09-21.

- ^ a b c d e f Clapp R, Polly Hoppin, Jyotsna Jagai, Sara Donahue. "Case Studies in Science Policy: Perfluorooctanoic Acid". Project on Scientific Knowledge and Public Policy (SKAPP). Archived from the original on 2009-03-01. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- ^ "Robert Bilott, The Right Livelihood Award". The Right Livelihood Award. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ "DuPont vs. the World: Chemical Giant Covered Up Health Risks of Teflon Contamination Across Globe". Democracy Now!. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-471-23896-6.

- ^ a b Goeden H (June 2008). Issues and Needs for PFAA Exposure and Health Research: A State Perspective (PDF). PFAA Days II. Minnesota Department of Health. U.S. EPA – Research Triangle Park. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- ^ PMID 15694468.

- S2CID 33348790.

- Norwegian Pollution Control Authority. 2007. p. 6. Retrieved 6 April 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Information on PFOA". DuPont. Archived from the original on 24 May 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ^ Siegle L (11 October 2009). "Do environmentally friendly outdoor jackets exist?". The Observer. London. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ^ PMID 12820537.

- PMID 16946516.

- PMID 20875479.

- ^ Sandy M. Petition for Expedited CIC Consideration of Perfluorooctanic Acid (PFOA) (PDF). State of California, Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, Cancer Toxicology and Epidemiology Section, Reproductive and Cancer Hazard Assessment Branch. Retrieved 2008-09-27.

- ^ PMID 17519394.

- .

- ^ "Learn More About DuPont Teflon". DuPont. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2009.

- ^ PMID 12831000.

- ^ G. Siegemund, W. Schwertfeger, A. Feiring, B. Smart, F. Behr, H. Vogel, B. McKusick (2005). "Fluorine Compounds, Organic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH.

- ^ EPA (7 March 2006). "Premanufacture Notification Exemption for Polymers; Amendment of Polymer Exemption Rule to Exclude Certain Perfluorinated Polymers; Proposed Rule" (PDF). Federal Register. 71 (44): 11490.

- ^ a b Guo Z, Liu X, Krebs KA (March 2009). "Perfluorocarboxylic Acid Content in 116 Articles of Commerce" (PDF). EPA. p. 40.

- ^ PMID 17520044.

- ^ "PFAS Fact Sheet" (PDF). Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- PMID 15913661.

- PMID 18589941.

- ^ a b https://casaweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/National-PFAS-Receivers-Factsheet.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ PMID 16786681.

- PMID 20493516.

- ^ PMID 18351063.

- PMID 25889547.

- S2CID 214766390.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 19731646.

- PMID 16213555.

- PMID 20149408.

- PMID 20471065.

- ^ PMID 18007991.

- PMID 18677976.

- ^ Fuchs E, Sohn P (10 February 2008). "Study finds high levels of stain-resistance ingredient in Conasauga River". Chattanooga Times Free Press. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2008.

- PMID 18653937.

- PMID 19117653.

- ^ "Substance flow analysis for Switzerland: Perfluorinated surfactants perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)". The Swiss Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN). 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ PMID 25426868.

- ^ PMID 26526296.

- ^ PMID 17695887.

- PMID 16570609.

- S2CID 4405763.

- PMID 12866900.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2007-08-21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-07. Retrieved 2008-09-19.)

{{cite conference}}: CS1 maint: others (link - PMID 17180988.

- PMID 18323078.

- PMID 20146964.

- ^ a b "Availability of Draft Toxicological Profile: Perfluoroalkyls". Federal Register. 22 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- PMID 20925396.

- PMID 21059488.

- ^ PMID 19350885.

- ^ Post G, Stern, Alan, Murphy, Eileen. "Guidance for PFOA in Drinking Water at Pennsgrove Water Supply Company" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection; Division of Science, Research and Technology. p. 2. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- ^ Johnson M. "Evaluation of Methodologies for Deriving Health-Based Values for PFCs in Drinking Water" (PDF). Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. pp. 20, 37. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- ^ "Information on PFOA". DuPont. Archived from the original on 24 May 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ^ .

- ^ S2CID 44370267.

- ISBN 978-0-7627-9071-5.

- ^ Dan Turner, LinkedIn[dead link], retrieved 9/26/15.

- ^ Weise E (16 November 2005). "Engineer: DuPont hid facts about paper coating". USA Today. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- ^ "Teflon firm faces fresh lawsuit". BBC News. 19 July 2005. Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- ^ "PFOA in Norway TA-2354/2007" (PDF). Norwegian Pollution Control Authority. 2007. p. 18. Retrieved 29 August 2009.[permanent dead link]

- S2CID 10777081.

- ^ "Nonstick pans: Nonstick coating risks". Consumer Reports. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- ^ Ward K Jr (17 January 2009). "EPA's C8 advisory does not address long-term risks". The Charleston Gazette. Archived from the original on 2011-06-24. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- PMID 20949951.

- PMID 21247105.

- ^ a b Finn S (15 January 2009). "Bush EPA sets so-called safe level of C8 in drinking water". West Virginia Public Broadcasting. Archived from the original on 20 January 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- ^ "Perfluorochemical Contamination of Biosolids Near Decatur, Alabama". EPA. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- ^ PMID 21334069.

- PMID 30634020.

- PMID 15984763.

- ^ "Drinking Water Health Advisories for PFOA and PFOS". EPA. 2020-12-09.

- ^ EPA (2016-05-25). "Lifetime Health Advisories and Health Effects Support Documents for Perfluorooctanoic Acid and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate." Federal Register, 81 FR 33250

- ^ EPA (2021-03-03). "Announcement of Final Regulatory Determinations for Contaminants on the Fourth Drinking Water Contaminant Candidate List." Federal Register, 86 FR 12272

- ^ a b "Adoption of ground water quality standards and maximum contaminant levels for perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS)". Trenton, NJ: New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP). 2020-06-01.

- ^ a b Fallon S (2018-09-06). "New Jersey becomes first state to regulate dangerous chemical PFNA in drinking water". North Jersey Record. Woodland Park, NJ.

- ^ a b "Drinking Water Quality Council Recommends Nation's Most Protective Maximum Contaminant Levels for Three Unregulated Contaminants in Drinking Water". Albany, NY: New York State Department of Health. 2018-12-18. Press release.

- ^ Snider A (14 May 2018). "White House, EPA headed off chemical pollution study". Politico. Retrieved May 20, 2018.

- ^ Benevento D (22 June 2018). "Response to PFAS contamination is coordinated and effective". The Denver Post. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- Public Health Service. p. 34. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- PMID 32625773.

- ^ "Chemical Used to Make Non-Stick Coatings Harmful to Health". Environment News Service. 13 May 2008. Retrieved 19 October 2008.

- ^ Hogue C (September 2008). "California Chemical Legislation: State's new laws on chemicals could presage federal action". Chemical & Engineering News. 86 (36): 9.

- ^ a b "Calif. law establishes chemical review". San Francisco Chronicle. Associated Press. 29 September 2008. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- S2CID 45472256.

- PMID 18007977.

- PMC 2516576.

- PMID 19440492.

- ^ "Assessment of PFOA in the drinking water of the German Hochsauerlandkreis" (PDF). Drinking Water Commission (Trinkwasserkommission) of the German Ministry of Health at the Federal Environment Agency. pp. 2–3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2009.

- S2CID 265571186.

- ^ S2CID 8653328.

- PMID 19569653.

- PMID 18648086.

- PMID 20123620.

- ^ PMID 20423814.

- PMID 20488749.

- ^ PMID 20089479.

- PMID 18678038.

- S2CID 30289350.

- PMID 19176540.

- PMID 19590684.

- S2CID 9787611.

- PMID 20123614.

- PMID 20551004.

- ^ Ken Ward Jr. "PFOA linked to ADHD and hormone disruption in kids". Blogs @ The Charleston Gazette. Retrieved 8 November 2009.

- .

- ^ "Patterns of age of puberty among children in the Mid-Ohio Valley in relation to Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS)" (PDF). C8 Science Panel. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- PMID 27137816.

- PMID 22306490.

- PMID 23680941.

- PMID 24803403.

- ^ S2CID 1447174.

- PMID 19351918.

- PMID 20800832.

- PMID 21062688.

- PMID 18941583.

- ^ C8 Science Panel

- PMID 19846564.

- PMID 20049206.

- ^ "Timeline". C8 Science Panel. Archived from the original on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ^ "C8 Science Panel Website". C8sciencepanel.org. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- ^ Cortese A (8 August 2004). "DuPont, Now in the Frying Pan". The New York Times. p. 3. Retrieved 30 December 2008.

- ^ Summers C (7 October 2004). "Teflon's sticky situation". BBC News. Retrieved 30 December 2008.

- ^ Biomonitoring: EPA Needs to Coordinate Its Research Strategy and Clarify Its Authority to Obtain Biomonitoring Data (PDF) (Report). US Government Accountability Office. April 2009. pp. 19–20. GAO-09-353. Retrieved 19 June 2009.

- ^ "Relationship of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) with pregnancy outcome among women with elevated community exposure to PFOA" (PDF). C8 Science Panel. Retrieved 27 June 2009.

- ^ "C8 Study Results – Status Reports". C8 Science Panel. Archived from the original on 2008-11-21. Retrieved 27 June 2009.

- ^ "Stockholm Convention COP.9 – Meeting documents". chm.pops.int. Retrieved 2021-01-14.

- ^ "Updated indicative list of substances covered by the listing of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), its salts and PFOA-related compounds". pops.int. UNEP/POPS/POPRC.17/INF/14/Rev.1. 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "PFAS and Fluorinated Compounds in PubChem Tree". PubChem Classification Browser. NCBI. Retrieved 2022-10-21. → Regulatory PFAS collections → PFOA and related substances

- ^ The Charleston Gazette.

- ^ [1] , et al. v. E.I. Du Pont De Nemours and Company Settlement ans Lubeck Public Service District at the Wayback Machine (archived September 19, 2010)

- ^ Janofsky M (2005-12-15). "DuPont to Pay $16.5 Million for Unreported Risks". The New York Times.

- ^ Goodwin, C.J. "Rhodes, et al. v. E.I. Du Pont De Nemours and Company" Archived 2010-05-27 at the Wayback Machine United States District Court for the Southern District of West Virginia. Case Number, 6:06-cv-530 (30 September 2008). Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ [2] Archived May 27, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gensler L. "DuPont Puts Toxic Exposure Lawsuits Behind It With $671 Million Settlement". Forbes. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

- ^ "2010/15 PFOA Stewardship Program; PFOA and Fluorinated Telomers". EPA. Archived from the original on 27 October 2008. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- PMID 16646434.

- ^ SAB Review of EPA's Draft Risk Assessment of Potential Human Health Effects Associated with PFOA and Its Salts (PDF). EPA Science Advisory Board. 2006-05-30. p. 2. Retrieved 2008-09-21.

- ^ Mid-Atlantic Enforcement (10 May 2007). "Fact Sheet: EPA, DuPont Agree on Measures to Protect Drinking Water Near the DuPont Washington Works". EPA. Archived from the original on 18 January 2008. Retrieved 11 May 2008.

- ^ "Drinking Water Health Advisories for PFOA and PFOS". EPA. 19 May 2016.

- ^ "EPA Announces New Drinking Water Health Advisories for PFAS Chemicals, $1 Billion in Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Funding to Strengthen Health Protections". EPA. 2022-06-15. News release.

- ^ RIN 2050-AH09

- ^ EPA. "Addressing PFOA and PFOS in the Environment: Potential Future Regulation Pursuant to the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act." Rulemaking Docket EPA-HQ-OLEM-2019-0341

- ^ "Proposed PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation". EPA. 2023-09-22.

- ^ EPA (2023-03-29). "PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation Rulemaking." Proposed rule. Federal Register, 88 FR 18638

- ^ PMID 17547148.

- ^ "Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) for Perfluorononanoic Acid and 1,2,3-Trichloropropane; Private Well Testing for Arsenic, Gross Alpha Particle Activity, and Certain Synthetic Organic Compounds". NJDEP. 2018-09-04. 50 N.J.R. 1939(a).

- ^ "AG Grewal, DEP Commissioner Announce 4 New Environmental Lawsuits Focused on Contamination Allegedly Linked to DuPont, Chemours, 3M". Totowa, NJ: New Jersey Office of the Attorney General. 2019-03-27. Press release.

- ^ Ellison G (2017-11-13). "Michigan creates multi-agency PFAS pollution response team". MLive. Archived from the original on 2022-04-01. Retrieved 2022-04-23.

- ^ "Michigan abruptly sets PFAS cleanup rules". mlive. 2018-01-10. Retrieved 2022-03-27.

- ^ "New state drinking water standards pave way for expansion of Michigan's PFAS clean-up efforts". Michigan.gov. 3 August 2020. Archived from the original on 3 January 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ Matheny K (3 August 2020). "Michigan's drinking water standards for these chemicals now among toughest in nation". Detroit Free Press. Archived from the original on 31 January 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "Health officials issue new health guidelines for PFOA, PFOS". Minnesota Department of Health. 2007-03-01. News Release. Archived from the original on 2007-08-14.

- .

- S2CID 95762541. Archived from the originalon 2008-09-05. Retrieved 2008-10-04.

- ^ "Risicoschatting emissie PFOA voor omwonenden : Locatie: DuPont/Chemours, Dordrecht, Nederland". rivm.nl. Retrieved 2016-08-31.

- ^ Official Journal of the European Union, L 150, 14 June 2017.

- ^ Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2020/784 of 8 April 2020 amending Annex I to Regulation (EU) 2019/1021 of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards the listing of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), its salts and PFOA-related compounds (Text with EEA relevance), 2020-06-15, retrieved 2021-01-14

- ^ Gayner O (2016-08-10). "Press Release: Williamtown Contamination Class Action". LinkedIn. IMF Bentham. Retrieved 2016-08-22.

External links

- US EPA: Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) – Overview, regulatory actions, tools & resources

- Sustained Outrage Blog – C8 (PFOA) Category Archived 2010-04-02 at the Charleston Gazette

- Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA); Fluorinated Telomers enforceable consent agreement development

- Perfluorinated substances and their uses in Sweden

- Chain of Contamination: The Food Link, Perfluorinated Chemicals (PFCs) Incl. PFOS & PFOA