Physical geography

| Part of a series on |

| Geography |

|---|

|

Physical geography (also known as physiography) is one of the three main branches of geography.[1][2][3][4][5] Physical geography is the branch of natural science which deals with the processes and patterns in the natural environment such as the atmosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere, and geosphere. This focus is in contrast with the branch of human geography, which focuses on the built environment, and technical geography, which focuses on using, studying, and creating tools to obtain, analyze, interpret, and understand spatial information.[4][5][6] The three branches have significant overlap, however.

Sub-branches

Physical geography can be divided into several branches or related fields, as follows:

- fluvial geomorphology; however, these sub-fields are united by the core processes which cause them, mainly tectonic or climatic processes. Geomorphology seeks to understand landform history and dynamics, and predict future changes through a combination of field observation, physical experiment, and numerical modeling (Geomorphometry). Early studies in geomorphology are the foundation for pedology, one of two main branches of soil science.

- hydrological cycle. Thus the field encompasses water in rivers, lakes, aquifers and to an extent glaciers, in which the field examines the process and dynamics involved in these bodies of water. Hydrology has historically had an important connection with engineering and has thus developed a largely quantitative method in its research; however, it does have an earth science side that embraces the systems approach. Similar to most fields of physical geography it has sub-fields that examine the specific bodies of water or their interaction with other spheres e.g. limnology and ecohydrology.

- glacial geology.

- .

- Climatology[7][8] is the study of the climate, scientifically defined as weather conditions averaged over a long period of time. Climatology examines both the nature of micro (local) and macro (global) climates and the natural and anthropogenic influences on them. The field is also sub-divided largely into the climates of various regions and the study of specific phenomena or time periods e.g. tropical cyclone rainfall climatology and paleoclimatology.

- Soil geography deals with the distribution of soils across the soil life (micro-organisms, plants, animals) and mineral materials within soils (biogeochemical cycles).

- Wilson cycle.

- sea level change.

- chemical oceanography). These diverse topics reflect multiple disciplines that oceanographers blend to further knowledge of the world ocean and understanding of processes within it.

- interstadial the Holoceneand uses proxy evidence to reconstruct the past environments during this period to infer the climatic and environmental changes that have occurred.

- Landscape ecology is a sub-discipline of ecology and geography that address how spatial variation in the landscape affects ecological processes such as the distribution and flow of energy, materials, and individuals in the environment (which, in turn, may influence the distribution of landscape "elements" themselves such as hedgerows). The field was largely funded by the German geographer Carl Troll. Landscape ecology typically deals with problems in an applied and holistic context. The main difference between biogeography and landscape ecology is that the latter is concerned with how flows or energy and material are changed and their impacts on the landscape whereas the former is concerned with the spatial patterns of species and chemical cycles.

- Geomatics is the field of gathering, storing, processing, and delivering geographic information, or spatially referenced information. Geomatics includes geodesy (scientific discipline that deals with the measurement and representation of the earth, its gravitational field, and other geodynamic phenomena, such as crustal motion, oceanic tides, and polar motion), cartography, geographical information science (GIS) and remote sensing (the short or large-scale acquisition of information of an object or phenomenon, by the use of either recording or real-time sensing devices that are not in physical or intimate contact with the object).

- Environmental geography is a branch of geography that analyzes the spatial aspects of interactions between humans and the natural world. The branch bridges the divide between human and physical geography and thus requires an understanding of the dynamics of geology, meteorology, hydrology, biogeography, and geomorphology, as well as the ways in which human societies conceptualize the environment. Although the branch was previously more visible in research than at present with theories such as environmental determinismlinking society with the environment. It has largely become the domain of the study of environmental management or anthropogenic influences.

Journals and literature

Main category: Geography Journals

Mental geography and earth science journals communicate and document the results of research carried out in universities and various other research institutions. Most journals cover a specific publish the research within that field, however unlike human geographers, physical geographers tend to publish in inter-disciplinary journals rather than predominantly geography journal; the research is normally expressed in the form of a

- Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society

- Climatic Change

- Earth Interactions

- Earth Surface Processes and Landforms

- Geographia Technica

- Geographical Bulletin

- Geomorphology

- Geophysical Research Letters

- Journal of Climate

- Journal of Coastal Research

- Journal of Biogeography

- Journal of Geography and Geology

- Journal of Geocryology

- Journal of Glaciology

- Journal of Hydrology

- Journal of Hydrometeorology

- Journal of Maps

- Journal of Quaternary Science

- Landscape Ecology

- Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences

- Nature

- Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology

- Polar Research

- Progress in Physical Geography

- Remote Sensing of Environment

- Sedimentology

- Soil Science

- The Professional Geographer

- Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers

Historical evolution of the discipline

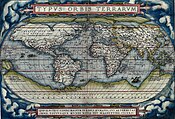

From the birth of geography as a science during the Greek classical period and until the late nineteenth century with the birth of anthropogeography (human geography), geography was almost exclusively a natural science: the study of location and descriptive gazetteer of all places of the known world. Several works among the best known during this long period could be cited as an example, from Strabo (Geography), Eratosthenes (Geographika) or Dionysius Periegetes (Periegesis Oiceumene) in the Ancient Age. In more modern times, these works include the Alexander von Humboldt (Kosmos) in the nineteenth century, in which geography is regarded as a physical and natural science through the work Summa de Geografía of Martín Fernández de Enciso from the early sixteenth century, which indicated for the first time the New World.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a controversy exported from geology, between supporters of James Hutton (uniformitarianism thesis) and Georges Cuvier (catastrophism) strongly influenced the field of geography, because geography at this time was a natural science.

Two historical events during the nineteenth century had a great effect on the further development of physical geography. The first was the European colonial expansion in Asia, Africa, Australia and even America in search of raw materials required by industries during the Industrial Revolution. This fostered the creation of geography departments in the universities of the colonial powers and the birth and development of national geographical societies, thus giving rise to the process identified by Horacio Capel as the institutionalization of geography.

The

The contributions of the Russian school became more frequent through his disciples, and in the nineteenth century we have great geographers such as

The second important process is the theory of evolution by Darwin in mid-century (which decisively influenced the work of Friedrich Ratzel, who had academic training as a zoologist and was a follower of Darwin's ideas) which meant an important impetus in the development of Biogeography.

Another major event in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries took place in the United States. William Morris Davis not only made important contributions to the establishment of discipline in his country but revolutionized the field to develop cycle of erosion theory which he proposed as a paradigm for geography in general, although in actually served as a paradigm for physical geography. His theory explained that mountains and other landforms are shaped by factors that are manifested cyclically. He explained that the cycle begins with the lifting of the relief by geological processes (faults, volcanism, tectonic upheaval, etc.). Factors such as rivers and runoff begin to create V-shaped valleys between the mountains (the stage called "youth"). During this first stage, the terrain is steeper and more irregular. Over time, the currents can carve wider valleys ("maturity") and then start to wind, towering hills only ("senescence"). Finally, everything comes to what is a plain flat plain at the lowest elevation possible (called "baseline") This plain was called by Davis' "peneplain" meaning "almost plain" Then river rejuvenation occurs and there is another mountain lift and the cycle continues.

Although Davis's theory is not entirely accurate, it was absolutely revolutionary and unique in its time and helped to modernize and create a geography subfield of

Notable physical geographers

- Eratosthenes (276 – 194 BC) who invented the discipline of geography.[12] He made the first known reliable estimation of the Earth's size.[13] He is considered the father of mathematical geography and geodesy.[13][14]

- Ptolemy (c. 90 – c. 168), who compiled Greek and Roman knowledge to produce the book Geographia.

- ]

- uniformitarianism in Kitāb al-Šifāʾ (also called The Book of Healing).

- Muhammad al-Idrisi (Dreses, 1100 – c. 1165), who drew the Tabula Rogeriana, the most accurate world map in pre-modern times.[17]

- Piri Reis (1465 – c. 1554), whose Piri Reis map is the oldest surviving world map to include the Americas and possibly Antarctica

- Gerardus Mercator (1512–1594), an innovative cartographer and originator of the Mercator projection.

- Bernhardus Varenius (1622–1650), Wrote his important work "General Geography" (1650), first overview of the geography, the foundation of modern geography.

- Mikhail Lomonosov (1711–1765), father of Russian geography and founded the study of glaciology.

- Cosmosand founded the study of biogeography.

- Arnold Henry Guyot (1807–1884), who noted the structure of glaciers and advanced the understanding of glacial motion, especially in fast ice flow.

- Louis Agassiz (1807–1873), the author of a glacial theory which disputed the notion of a steady-cooling Earth.

- Wallace line.

- Vasily Dokuchaev (1840–1903), patriarch of Russian geography and founder of pedology.

- Wladimir Peter Köppen(1846–1940), developer of most important climate classification and founder of Paleoclimatology.

- William Morris Davis (1850–1934), father of American geography, founder of Geomorphology and developer of the geographical cycle theory.

- FRGS(1854-1911), wrote his seminal work Geography of the Oceans published in 1881.

- Walther Penck (1888–1923), proponent of the cycle of erosion and the simultaneous occurrence of uplift and denudation.

- Sir Ernest Shackleton (1874–1922), Antarctic explorer during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

- overland flow.

- Bretz (Missoula) floods.

- Luis García Sáinz(1894–1965), pioneer of physical geography in Spain.

- Dansgaard-Oeschger events.

- Hans Oeschger (1927–1998), palaeoclimatologist and pioneer in ice core research, co-identifier of Dansgaard-Orschger events.

- Richard Chorley (1927–2002), a key contributor to the quantitative revolution and the use of systems theory in geography.

- Sir Nicholas Shackleton (1937–2006), who demonstrated that oscillations in climate over the past few million years could be correlated with variations in the orbital and positional relationship between the Earth and the Sun.

See also

- Areography

- Atmosphere of Earth

- Concepts and Techniques in Modern Geography

- Earth system science

- Environmental science

- Environmental studies

- Geographic information science

- Geographic information system

- Geophysics

- Geostatistics

- Global Positioning System

- Planetary science

- Physiographic regions of the world

- Selenography

- Technical geography

References

- ^ "1(b). Elements of Geography". www.physicalgeography.net.

- ^ Pidwirny, Michael; Jones, Scott (1999–2015). "Physical Geography".

- ISBN 9780521764285.

- ^ ISBN 9780137504510. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- doi:10.36962/GBSSJAR/59.3.004 (inactive 2024-02-14).)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of February 2024 (link - ^ a b c d e f "Physical Geography: Defining Physical Geography". Dartmouth College Library. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- ^ a b c d e "Physical Geography". University of Nevada, Reno.

- ^ "Subdisciplines of Geography". Civil Service India (PNG).

Soils Geography lies between Physical Geography and Pedology

- S2CID 131268490.

(Soil geography) is a branch of study which lies between geography and soil science and is to be found as a fundamental part of both subjects (Bridges and Davidson, 1981)

- ISSN 0033-2143– via RCIN.

soil geography may be defined as a scientific discipline - within both geography and soil science - that deals with the distribution of soils across the Earth's surface

- M. Degórski (January 2004). "Soil geography as a physical geography discipline". ResearchGate.

- ISBN 978-0-691-14267-8.

- ^ a b Avraham Ariel, Nora Ariel Berger (2006)."Plotting the globe: stories of meridians, parallels, and the international". Greenwood Publishing Group. p.12.

ISBN 0-275-98895-3

- ISBN 1-58341-430-4

- ^ Akbar S. Ahmed (1984). "Al-Beruni: The First Anthropologist", RAIN 60, pp. 9–10.

- ^ H. Mowlana (2001). "Information in the Arab World", Cooperation South Journal 1.

- ^ S. P. Scott (1904), History of the Moorish Empire, pp. 461–2:

The compilation of Edrisi marks an era in the history of science. Not only is its historical information most interesting and valuable, but its descriptions of many parts of the earth are still authoritative. For three centuries geographers copied his maps without alteration. The relative position of the lakes which form the Nile, as delineated in his work, does not differ greatly from that established by Baker and Stanley more than seven hundred years afterward, and their number is the same.

Further reading

- Holden, Joseph. (2004). Introduction to Physical Geography and the Environment. Prentice-Hall, London.

- Inkpen, Robert. (2004). Science, Philosophy and Physical Geography. Routledge, London.

- Pidwirny, Michael. (2014). Glossary of Terms for Physical Geography. Planet Earth Publishing, Kelowna, Canada. ISBN 9780987702906. Available on Google Play.

- Pidwirny, Michael. (2014). Understanding Physical Geography. Planet Earth Publishing, Kelowna, Canada. ISBN 9780987702944. Available on Google Play.

- Reynolds, Stephen J. et al. (2015). Exploring Physical Geography. [A Visual Textbook, Featuring more than 2500 Photographies & Illustrations]. McGraw-Hill Education, New York. ISBN 978-0-07-809516-0

- Smithson, Peter; et al. (2002). Fundamentals of the Physical Environment. Routledge, London.

- Strahler, Alan; Strahler Arthur. (2006). Introducing Physical Geography. Wiley, New York.

- Summerfield, M. (1991). Global Geomorphology. Longman, London.

- Wainwright, John; Mulligan, M. (2003). Environmental Modelling: Finding Simplicity in Complexity. John Wiley and Sons Ltd, London.

External links

- Physiography by T.X. Huxley, 1878, full text, physical geography of the Thames River Basin

- Fundamentals of Physical Geography, 2nd Edition, by M. Pidwirny, 2006, full text

- Physical Geography for Students and Teachers, UK National Grid For Learning