Rosetta Stone

| Rosetta Stone | |

|---|---|

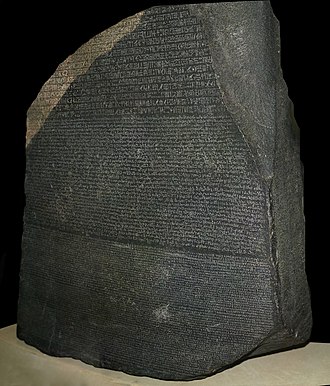

The Rosetta Stone on display in the British Museum, London | |

| Material | Granodiorite |

| Size | 1,123 mm × 757 mm × 284 mm (44.2 in × 29.8 in × 11.2 in) |

| Writing | Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, Demotic script, and Greek script |

| Created | 196 BC |

| Discovered | 1799 near Rosetta, Nile Delta, Egypt |

| Discovered by | Pierre-François Bouchard |

| Present location | British Museum |

The Rosetta Stone is a stele of granodiorite inscribed with three versions of a decree issued in 196 BC during the Ptolemaic dynasty of Egypt, on behalf of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes. The top and middle texts are in Ancient Egyptian using hieroglyphic and Demotic scripts, respectively, while the bottom is in Ancient Greek. The decree has only minor differences across the three versions, making the Rosetta Stone key to deciphering the Egyptian scripts.

The stone was carved during the

Study of the decree was already underway when the first complete translation of the Greek text was published in 1803. Jean-François Champollion announced the transliteration of the Egyptian scripts in Paris in 1822; it took longer still before scholars were able to read Ancient Egyptian inscriptions and literature confidently. Major advances in the decoding were recognition that the stone offered three versions of the same text (1799); that the Demotic text used phonetic characters to spell foreign names (1802); that the hieroglyphic text did so as well, and had pervasive similarities to the Demotic (1814); and that phonetic characters were also used to spell native Egyptian words (1822–1824).

Three other fragmentary copies of the same decree were discovered later, and several similar Egyptian

Description

The Rosetta Stone is listed as "a stone of black

The Rosetta Stone is 112.3 cm (3 ft 8 in) high at its highest point, 75.7 cm (2 ft 5.8 in) wide, and 28.4 cm (11 in) thick. It weighs approximately 760 kilograms (1,680 lb).

Original stele

The Rosetta Stone is a fragment of a larger stele. No additional fragments were found in later searches of the Rosetta site.[11] Owing to its damaged state, none of the three texts is complete. The top register, composed of Egyptian hieroglyphs, suffered the most damage. Only the last 14 lines of the hieroglyphic text can be seen; all of them are broken on the right side, and 12 of them on the left. Below it, the middle register of demotic text has survived best; it has 32 lines, of which the first 14 are slightly damaged on the right side. The bottom register of Greek text contains 54 lines, of which the first 27 survive in full; the rest are increasingly fragmentary due to a diagonal break at the bottom right of the stone.[12]

Memphis decree and its context

The stele was erected after the

The decree was issued during a turbulent period in Egyptian history. Ptolemy V Epiphanes, the son of

Political forces beyond the borders of Egypt exacerbated the internal problems of the Ptolemaic kingdom.

Stelae of this kind, which were established on the initiative of the temples rather than that of the king, are unique to Ptolemaic Egypt. In the preceding Pharaonic period it would have been unheard of for anyone but the divine rulers themselves to make national decisions: by contrast, this way of honouring a king was a feature of Greek cities. Rather than making his eulogy himself, the king had himself glorified and deified by his subjects or representative groups of his subjects.[24] The decree records that Ptolemy V gave a gift of silver and grain to the temples.[25] It also records that there was particularly high flooding of the Nile in the eighth year of his reign, and he had the excess waters dammed for the benefit of the farmers.[25] In return the priesthood pledged that the king's birthday and coronation days would be celebrated annually and that all the priests of Egypt would serve him alongside the other gods. The decree concludes with the instruction that a copy was to be placed in every temple, inscribed in the "language of the gods" (Egyptian hieroglyphs), the "language of documents" (Demotic), and the "language of the Greeks" as used by the Ptolemaic government.[26][27]

Securing the favour of the priesthood was essential for the Ptolemaic kings to retain effective rule over the populace. The

There can be no one definitive English translation of the decree, not only because modern understanding of the ancient languages continues to develop, but also because of the minor differences between the three original texts. Older translations by

The stele was almost certainly not originally placed at Rashid (Rosetta) where it was found, but more likely came from a temple site farther inland, possibly the royal town of Sais.[35] The temple from which it originally came was probably closed around AD 392 when Roman emperor Theodosius I ordered the closing of all non-Christian temples of worship.[36] The original stele broke at some point, its largest piece becoming what we now know as the Rosetta Stone. Ancient Egyptian temples were later used as quarries for new construction, and the Rosetta Stone probably was re-used in this manner. Later it was incorporated in the foundations of a fortress constructed by the Mameluke Sultan Qaitbay (c. 1416/18–1496) to defend the Bolbitine branch of the Nile at Rashid. There it lay for at least another three centuries until its rediscovery.[37]

Three other inscriptions relevant to the same Memphis decree have been found since the discovery of the Rosetta Stone: the

Rediscovery

The discovery was reported in September in

After Napoleon's departure, French troops held off British and Ottoman attacks for another 18 months. In March 1801, the British landed at Aboukir Bay. Menou was now in command of the French expedition. His troops, including the commission, marched north towards the Mediterranean coast to meet the enemy, transporting the stone along with many other antiquities. He was defeated in battle, and the remnant of his army retreated to Alexandria where they were surrounded and besieged, with the stone now inside the city. Menou surrendered on 30 August.[42][43]

From French to British possession

After the surrender, a dispute arose over the fate of the French archaeological and scientific discoveries in Egypt, including the artefacts, biological specimens, notes, plans, and drawings collected by the members of the commission. Menou refused to hand them over, claiming that they belonged to the institute. British General John Hely-Hutchinson refused to end the siege until Menou gave in. Scholars Edward Daniel Clarke and William Richard Hamilton, newly arrived from England, agreed to examine the collections in Alexandria and said they had found many artefacts that the French had not revealed. In a letter home, Clarke wrote that "we found much more in their possession than was represented or imagined".[44]

Hutchinson claimed that all materials were property of the

It is not clear exactly how the stone was transferred into British hands, as contemporary accounts differ. Colonel Tomkyns Hilgrove Turner, who was to escort it to England, claimed later that he had personally seized it from Menou and carried it away on a gun-carriage. In a much more detailed account, Edward Daniel Clarke stated that a French "officer and member of the Institute" had taken him, his student John Cripps, and Hamilton secretly into the back streets behind Menou's residence and revealed the stone hidden under protective carpets among Menou's baggage. According to Clarke, their informant feared that the stone might be stolen if French soldiers saw it. Hutchinson was informed at once and the stone was taken away—possibly by Turner and his gun-carriage.[47]

Turner brought the stone to England aboard the captured French frigate

In 1802, the Society created four plaster casts of the inscriptions, which were given to the universities of Oxford, Cambridge and Edinburgh and to Trinity College Dublin. Soon afterwards, prints of the inscriptions were made and circulated to European scholars.[E] Before the end of 1802, the stone was transferred to the British Museum, where it is located today.[48] New inscriptions painted in white on the left and right edges of the slab stated that it was "Captured in Egypt by the British Army in 1801" and "Presented by King George III".[2]

The stone has been exhibited almost continuously in the British Museum since June 1802. The Rosetta Stone was originally displayed at a slight angle from the horizontal, and rested within a metal cradle that was made for it, which involved shaving off very small portions of its sides to ensure that the cradle fitted securely.[50] It originally had no protective covering, and it was found necessary by 1847 to place it in a protective frame, despite the presence of attendants to ensure that it was not touched by visitors.[53] Since 2004 the conserved stone has been on display in a specially built case in the centre of the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery. A replica of the Rosetta Stone is now available in the King's Library of the British Museum, without a case and free to touch, as it would have appeared to early 19th-century visitors.[54]

The museum was concerned about

Reading the Rosetta Stone

Prior to the discovery of the Rosetta Stone and its eventual decipherment, the ancient

Hieroglyphs retained their pictorial appearance, and classical authors emphasised this aspect, in sharp contrast to the

Greek text

The Greek text on the Rosetta Stone provided the starting point. Ancient Greek was widely known to scholars, but they were not familiar with details of its use in the Hellenistic period as a government language in Ptolemaic Egypt; large-scale discoveries of Greek papyri were a long way in the future. Thus, the earliest translations of the Greek text of the stone show the translators still struggling with the historical context and with administrative and religious jargon. Stephen Weston verbally presented an English translation of the Greek text at a Society of Antiquaries meeting in April 1802.[65][66]

Meanwhile, two of the lithographic copies made in Egypt had reached the Institut de France in Paris in 1801. There, librarian and antiquarian Gabriel de La Porte du Theil set to work on a translation of the Greek, but he was dispatched elsewhere on Napoleon's orders almost immediately, and he left his unfinished work in the hands of colleague Hubert-Pascal Ameilhon. Ameilhon produced the first published translations of the Greek text in 1803, in both Latin and French to ensure that they would circulate widely.[H] At Cambridge, Richard Porson worked on the missing lower right corner of the Greek text. He produced a skilful suggested reconstruction, which was soon being circulated by the Society of Antiquaries alongside its prints of the inscription. At almost the same moment, Christian Gottlob Heyne in Göttingen was making a new Latin translation of the Greek text that was more reliable than Ameilhon's and was first published in 1803.[G] It was reprinted by the Society of Antiquaries in a special issue of its journal Archaeologia in 1811, alongside Weston's previously unpublished English translation, Colonel Turner's narrative, and other documents.[H][67][68]

Demotic text

At the time of the stone's discovery, Swedish diplomat and scholar

-

Copticequivalents (1802)

-

Replica of the Demotic texts

Hieroglyphic text

Silvestre de Sacy eventually gave up work on the stone, but he was to make another contribution. In 1811, prompted by discussions with a Chinese student about

Young did so, with two results that together paved the way for the final decipherment. In the hieroglyphic text, he discovered the phonetic characters "p t o l m e s" (in today's transliteration "p t w l m y s") that were used to write the Greek name "Ptolemaios". He also noticed that these characters resembled the equivalent ones in the demotic script, and went on to note as many as 80 similarities between the hieroglyphic and demotic texts on the stone, an important discovery because the two scripts were previously thought to be entirely different from one another. This led him to deduce correctly that the demotic script was only partly phonetic, also consisting of ideographic characters derived from hieroglyphs.[I] Young's new insights were prominent in the long article "Egypt" that he contributed to the Encyclopædia Britannica in 1819.[J] He could make no further progress, however.[71]

In 1814, Young first exchanged correspondence about the stone with

Later work

Work on the stone now focused on fuller understanding of the texts and their contexts by comparing the three versions with one another. In 1824 Classical scholar

Whether one of the three texts was the standard version, from which the other two were originally translated, is a question that has remained controversial. Letronne attempted to show in 1841 that the Greek version, the product of the Egyptian government under the Macedonian

Rivalries

Even before the Salvolini affair, disputes over precedence and plagiarism punctuated the decipherment story. Thomas Young's work is acknowledged in Champollion's 1822 Lettre à M. Dacier, but incompletely, according to early British critics: for example, James Browne, a sub-editor on the Encyclopædia Britannica (which had published Young's 1819 article), anonymously contributed a series of review articles to the Edinburgh Review in 1823, praising Young's work highly and alleging that the "unscrupulous" Champollion plagiarised it.[79][80] These articles were translated into French by Julius Klaproth and published in book form in 1827.[N] Young's own 1823 publication reasserted the contribution that he had made.[L] The early deaths of Young (1829) and Champollion (1832) did not put an end to these disputes. In his work on the stone in 1904 E. A. Wallis Budge gave special emphasis to Young's contribution compared with Champollion's.[81] In the early 1970s, French visitors complained that the portrait of Champollion was smaller than one of Young on an adjacent information panel; English visitors complained that the opposite was true. The portraits were in fact the same size.[52]

Requests for repatriation to Egypt

Calls for the Rosetta Stone to be returned to Egypt were made in July 2003 by

In 2005, the British Museum presented Egypt with a full-sized fibreglass colour-matched replica of the stele. This was initially displayed in the renovated Rashid National Museum, an Ottoman house in the town of Rashid (Rosetta), the closest city to the site where the stone was found.[86] In November 2005, Hawass suggested a three-month loan of the Rosetta Stone, while reiterating the eventual goal of a permanent return.[87] In December 2009, he proposed to drop his claim for the permanent return of the Rosetta Stone if the British Museum lent the stone to Egypt for three months for the opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum at Giza in 2013.[88]

As John Ray has observed: "The day may come when the stone has spent longer in the British Museum than it ever did in Rosetta."[89]

National museums typically express strong opposition to the repatriation of objects of international cultural significance such as the Rosetta Stone. In response to repeated Greek requests for return of the Elgin Marbles from the Parthenon and similar requests to other museums around the world, in 2002, over 30 of the world's leading museums—including the British Museum, the Louvre, the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, and the Metropolitan Museum in New York City—issued a joint statement:

Objects acquired in earlier times must be viewed in the light of different sensitivities and values reflective of that earlier era...museums serve not just the citizens of one nation but the people of every nation.[90]

Idiomatic use

Various ancient bilingual or even trilingual

The term Rosetta stone has been also used idiomatically to denote the first crucial key in the process of decryption of encoded information, especially when a small but representative sample is recognised as the clue to understanding a larger whole.[93] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first figurative use of the term appeared in the 1902 edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica relating to an entry on the chemical analysis of glucose.[93] Another use of the phrase is found in H. G. Wells's 1933 novel The Shape of Things to Come, where the protagonist finds a manuscript written in shorthand that provides a key to understanding additional scattered material that is sketched out in both longhand and on typewriter.[93]

Since then, the term has been widely used in other contexts. For example,

The name is used for various forms of

See also

- Egypt–United Kingdom relations

- Ezana Stone – Stele still standing in Axum in present-day Ethiopia

- Garshunography – use of the script of one language to write utterances of another language which already has a script associated with it.

- List of individual rocks

- Mesha Stele – Moabite stele commemorating Mesha's victory over Israel (c. 840 BCE)

- Multilingual inscription

- Transliteration of Ancient Egyptian

- Rosetta (spacecraft)

References

Timeline of early publications about the Rosetta Stone

- ^ 1799: Courrier de l'Égypte no. 37 (29 Fructidor year 7, i.e. 1799) p. 3 Retrieved July 15, 2018

- ^ 1802: "Domestic Occurrences: March 31st, 1802" in The Gentleman's Magazine vol. 72 part 1 p. 270 Retrieved July 14, 2010

- Silvestre de Sacy, Lettre au Citoyen Chaptal, Ministre de l'intérieur, Membre de l'Institut national des sciences et arts, etc: au sujet de l'inscription Égyptienne du monument trouvé à Rosette. Paris, 1802 Retrieved July 14, 2010

Notes

- ^ Bierbrier (1999) pp. 111–113

- ^ a b Parkinson et al. (1999) p. 23

- ^ Synopsis (1847) pp. 113–114

- ^ Miller et al. (2000) pp. 128–132

- ^ a b Middleton and Klemm (2003) pp. 207–208

- ^ a b The Rosetta Stone

- ^ a b c Ray (2007) p. 3

- ^ Solly, Meilan (27 September 2022). "Two Hundred Years Ago, the Rosetta Stone Unlocked the Secrets of Ancient Egypt". Smithsonian. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ISBN 978-3-030-86414-9.

- ^ Parkinson et al. (1999) p. 28

- ^ a b c Parkinson et al. (1999) p. 20

- ^ Budge (1913) pp. 2–3

- ^ Budge (1894) p. 106

- ^ Budge (1894) p. 109

- ^ a b Parkinson et al. (1999) p. 26

- ^ Parkinson et al. (1999) p. 25

- ^ Clarysse and Van der Veken (1983) pp. 20–21

- ^ a b c Parkinson et al. (1999) p. 29

- ^ Shaw & Nicholson (1995) p. 247

- ^ Tyldesley (2006) p. 194

- ^ a b Clayton (2006) p. 211

- ^ Bevan (1927) pp. 252–262

- ^ Assmann (2003) p. 376

- ^ Clarysse (1999) p. 51, with references there to Quirke and Andrews (1989)

- ^ a b Bevan (1927) pp. 264–265

- ^ Ray (2007) p. 136

- ^ Parkinson et al. (1999) p. 30

- ^ Shaw (2000) p. 407

- ^ Walker and Higgs (editors, 2001) p. 19

- ^ Bagnall and Derow (2004) (no. 137 in online version)

- ^ Budge (1904); Budge (1913)

- ^ Bevan (1927) pp. 263–268

- ^ Simpson (n. d.); a revised version of Simpson (1996) pp. 258–271

- ^ Quirke and Andrews (1989)

- ^ Parkinson (2005) p. 14

- ^ Parkinson (2005) p. 17

- ^ Parkinson (2005) p. 20

- ^ Clarysse (1999) p. 42; Nespoulous-Phalippou (2015) pp. 283–285

- ^ Parkinson et al. (1999) pp. 17–20

- ^ Adkins (2000) p. 38

- ^ Gillispie (1987) pp. 1–38

- ^ Wilson 1803, pp. 274–284.

- ^ a b c Parkinson et al. (1999) p. 21

- ^ Burleigh (2007) p. 212

- ^ Burleigh (2007) p. 214

- ^ Budge (1913) p. 2

- ^ Parkinson et al. (1999) pp. 21–22

- ^ a b Andrews (1985) p. 12

- ^ Parkinson (2005) pp. 30–31

- ^ a b Parkinson (2005) p. 31

- ^ Parkinson (2005) p. 7

- ^ a b c Parkinson (2005) p. 47

- ^ Parkinson (2005) p. 32

- ^ Parkinson (2005) p. 50

- ^ "Everything you ever wanted to know about the Rosetta Stone" (British Museum, 14 July 2017)

- ^ Parkinson (2005) pp. 50–51

- ^ Ray (2007) p. 11

- ^ Iversen (1993) p. 30

- ^ Parkinson et al. (1999) pp. 15–16

- ^ El Daly (2005) pp. 65–75

- ^ Ray (2007) pp. 15–18

- ^ Iversen (1993) pp. 70–72

- ^ Ray (2007) pp. 20–24

- ISBN 978-1-4051-6256-2.

- ^ a b Budge (1913) p. 1

- ^ Andrews (1985) p. 13

- ^ Budge (1904) pp. 27–28

- ^ Parkinson et al. (1999) p. 22

- ^ Robinson (2009) pp. 59–61

- ^ Robinson (2009) p. 61

- ^ Robinson (2009) pp. 61–64

- ^ Parkinson et al. (1999) p. 32

- ^ Budge (1913) pp. 3–6

- ISBN 978-94-015-9391-5.

- ^ Dewachter (1990) p. 45

- ^ Quirke and Andrews (1989) p. 10

- ^ Parkinson (2005) p. 13

- ^ Parkinson et al. (1999) pp. 30–31

- broken anchor] pp. 35–38

- ^ Robinson (2009) pp. 65–68

- ^ Budge (1904) vol. 1 pp. 59–134

- ^ Edwardes and Milner (2003)

- ^ Sarah El Shaarawi (5 October 2016). "Egypt's Own: Repatriation of Antiquities Proves to be a Mammoth Task". Newsweek – Middle East.

- ^ "'Return Rosetta Stone to Egypt' demands country's leading archaeologist Zahi Hawass". The Art Newspaper – International art news and events. 22 August 2022.

- ^ Stickings, Tim (19 August 2022). "New push to bring Rosetta Stone back to Egypt amid 'awakening' on colonial loot". The National.

- ^ "Rose of the Nile" (2005)

- ^ Huttinger (2005)

- ^ "Antiquities wish list" (2005)

- ^ Ray (2007) p. 4

- ^ Bailey (2003)

- ISBN 978-1-58839-452-1.

- ISBN 978-93-84544-31-7.

- ^ a b c d Oxford English dictionary (1989) s.v. "Rosetta stone" Archived June 20, 2011, at archive.today

- ^ "International Team"

- ^ Simpson and Dean (2002)

- ^ Cooper (2010)

- ^ Nishimura and Tajik (1998)

- ^ "Rosetta's Comet Target 'Releases' Plentiful Water". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Retrieved 19 November 2024.

Bibliography

- Adkins, Lesley; Adkins, R. A. (2000). The Keys of Egypt: the obsession to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-019439-0.

- Allen, Don Cameron (1960). "The Predecessors of Champollion". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 144 (5): 527–547.

- Andrews, Carol (1985). The Rosetta Stone. British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-87226-034-4.

- Assmann, Jan; Jenkins, Andrew (2003). The Mind of Egypt: history and meaning in the time of the Pharaohs. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01211-0. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- "Antiquities Wish List". Al-Ahram Weekly. 20 July 2005. Archived from the original on 16 September 2010. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- Bagnall, R. S.; Derow, P. (2004). The Hellenistic Period: historical sources in translation. Blackwell. ISBN 1-4051-0133-4. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- Bailey, Martin (21 January 2003). "Shifting the Blame". Forbes.com. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- Bevan, E. R. (1927). The House of Ptolemy. Methuen. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- Bierbrier, M. L. (1999). "The acquisition by the British Museum of antiquities discovered during the French invasion of Egypt". In Davies, W. V (ed.). Studies in Egyptian Antiquities. (British Museum Publications).

- Brown, V. M.; Harrell, J. A. (1998). "Aswan Granite and Granodiorite". Göttinger Miszellen. 164: 133–137.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (1894). The Mummy: chapters on Egyptian funereal archaeology. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (1904). The Decrees of Memphis and Canopus. Kegan Paul. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (1913). The Rosetta Stone. British Museum. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- Burleigh, Nina (2007). Mirage: Napoleon's scientists and the unveiling of Egypt. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-059767-2.

- Clarysse, G. W.; Van der Veken, G. (1983). The Eponymous Priests of Ptolemaic Egypt (P. L. Bat. 24): Chronological lists of the priests of Alexandria and Ptolemais with a study of the demotic transcriptions of their names. Assistance by S. P. Vleeming. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-06879-1.

- Clarysse, G. W. (1999). "Ptolémées et temples". In Valbelle, Dominique (ed.). Le Décret de Memphis: colloque de la Fondation Singer-Polignac a l'occasion de la celebration du bicentenaire de la découverte de la Pierre de Rosette. Paris.

- Clayton, Peter A. (2006). Chronicles of the Pharaohs: the reign-by-reign record of the rulers and dynasties of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28628-0.

- Cooper, Keith (14 April 2010). "New Rosetta Stone for GRBs as supernovae". Astronomy Now Online. Archived from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- Dewachter, M. (1990). ISBN 978-2-07-053103-5.

- Downs, Jonathan (2008). Discovery at Rosetta: the ancient stone that unlocked the mysteries of Ancient Egypt. Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60239-271-7.

- Edwardes, Charlotte; Milner, Catherine (20 July 2003). "Egypt demands return of the Rosetta Stone". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2006.

- El-Aref, Nevine (30 November 2005). "The Rose of the Nile". Al-Ahram Weekly.

- El Daly, Okasha (2005). Egyptology: the missing millennium: Ancient Egypt in medieval Arabic writings. UCL Press. ISBN 1-84472-063-2.

- Gillispie, C. C.; Dewachter, M. (1987). Monuments of Egypt: the Napoleonic edition. Princeton University Press. pp. 1–38.

- "Horwennefer". Egyptian Royal Genealogy. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- Huttinger, Henry (28 July 2005). "Stolen Treasures: Zahi Hawass wants the Rosetta Stone back—among other things". Cairo Magazine. Archived from the original on 1 December 2005. Retrieved 6 October 2006.

- "International team accelerates investigation of immune-related genes". The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. 6 September 2000. Archived from the original on 9 August 2007. Retrieved 23 November 2006.

- Iversen, Erik (1993) [First edition 1961]. The Myth of Egypt and Its Hieroglyphs in European Tradition. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02124-9.

- Kitchen, Kenneth A. (1970). "Two Donation Stelae in the Brooklyn Museum". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 8: 59–67. JSTOR 40000039.

- Meyerson, Daniel (2004). The Linguist and the Emperor: Napoleon and Champollion's quest to decipher the Rosetta Stone. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-45067-8.

- Middleton, A.; Klemm, D. (2003). "The Geology of the Rosetta Stone". Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 89 (1): 207–216. S2CID 126606607.

- Miller, E.; et al. (2000). "The Examination and Conservation of the Rosetta Stone at the British Museum". In Roy, A.; Smith, P (eds.). Tradition and Innovation. (British Museum Publications). pp. 128–132.

- Nespoulous-Phalippou, Alexandra (2015). Ptolémée Épiphane, Aristonikos et les prêtres d'Égypte. Le Décret de Memphis (182 a.C.): édition commentée des stèles Caire RT 2/3/25/7 et JE 44901 (CENiM 12). Montpellier: Université Paul Valéry.

- Nicholson, P. T.; Shaw, I. (2000). Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology. Cambridge University Press.

- Nishimura, Rick A.; Tajik, A. Jamil (23 April 1998). "Evaluation of diastolic filling of left ventricle in health and disease: Doppler echocardiography is the clinician's Rosetta Stone". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 30 (1): 8–18. PMID 9207615.

- Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press. 1989. ISBN 978-0-19-861186-8.

- ISBN 978-0-520-22306-6. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- ISBN 978-0-7141-5021-5.

- Quirke, Stephen; Andrews, Carol (1989). The Rosetta Stone. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-1572-5.

- ISBN 978-0-674-02493-9.

- Robinson, Andrew (2009). Lost Languages: the enigma of the world's undeciphered scripts. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-51453-5.

- "The Rosetta Stone". The British Museum. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- "Rosetta Stone row 'would be solved by loan to Egypt'". BBC News. 8 December 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- Shaw, Ian (2000). The Oxford history of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280458-8.

- Simpson, Gordon G.; Dean, Caroline (12 April 2002). "Arabidopsis, the Rosetta Stone of Flowering Time?". Science. 296 (5566): 285–289. PMID 11951029. Retrieved 23 November 2006.

- Shaw, Ian; Nicholson, Paul (1995). The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-9096-2.

- Simpson, R. S. (1996). Demotic Grammar in the Ptolemaic Sacerdotal Decrees. Griffith Institute. ISBN 978-0-900416-65-1.

- Simpson, R. S. (n.d.). "The Rosetta Stone: translation of the demotic text". The British Museum. Archived from the original on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- ISBN 978-1-56858-226-9.

- Spencer, Neal; Thorne, C. (2003). Book of Egyptian Hieroglyphs. British Museum Press, Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-0-7607-4199-3.

- Synopsis of the Contents of the British Museum. British Museum. 1847.

- ISBN 0-500-05145-3.

- Walker, Susan; Higgs, Peter, eds. (2001). Cleopatra of Egypt. British Museum Press. ISBN 0-7141-1943-1.

- Wilson, Robert Thomas (1803). History of the British Expedition to Egypt. 4th ed. Military Library. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

External links

- "British Museum Object Database reference number: EA24".

- "How the Rosetta Stone works". Howstuffworks.com. 11 December 2007.