Monterey Bay Aquarium: Difference between revisions

Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers 6,984 edits m →Political advocacy: split ref tag |

Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers 6,984 edits →Seafood program: added prominence |

||

| Line 120: | Line 120: | ||

Monterey Bay Aquarium’s [[consumer]]-based Seafood Watch program encourages [[sustainable seafood]] purchasing from [[Fishery|fisheries]] that are "well managed and caught or farmed in ways that cause little harm to habitats or other wildlife."<ref>{{cite news |last=Hiolski |first=Emma |date=October 5, 2016 |title=Carmel woman to be honored by White House |url=http://www.montereyherald.com/article/NF/20161005/NEWS/161009807 |work=The Monterey County Herald |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161209150222/http://www.montereyherald.com/article/NF/20161005/NEWS/161009807 |archive-date=December 9, 2016 |access-date=February 2, 2017 |ref=harv |deadurl=no}}</ref> It began in 1999 as a result of a popular component of a temporary exhibition and has grown to consist of a website, six regional pocket guides, and mobile apps that allow consumers to check the [[sustainability]] ratings of specific fisheries. The program has expanded to include business collaborations, local and national restaurant and grocer partnerships, and outreach partnerships—primarily other public aquariums and zoos. Large-scale business and grocer affiliations include [[Aramark]], [[Compass Group]], [[Target Corporation|Target]], and [[Whole Foods Market]].<ref name="bundle_seafoodpartners" /> In both 2009 and 2015, Seafood Watch was reportedly playing an influential role in the development of sustainable business practices within the global [[fishing industry]].<ref>{{harvnb|Parsons|2015}}; {{harvnb|Reynolds|2009}}.</ref> According to the aquarium, the program's efficacy is driven by its work with both businesses and consumers, and is supported by the aquarium's expanding science and ocean policy programs.{{sfn|Spring|2018|pp=159, 161–162}} |

Monterey Bay Aquarium’s [[consumer]]-based Seafood Watch program encourages [[sustainable seafood]] purchasing from [[Fishery|fisheries]] that are "well managed and caught or farmed in ways that cause little harm to habitats or other wildlife."<ref>{{cite news |last=Hiolski |first=Emma |date=October 5, 2016 |title=Carmel woman to be honored by White House |url=http://www.montereyherald.com/article/NF/20161005/NEWS/161009807 |work=The Monterey County Herald |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161209150222/http://www.montereyherald.com/article/NF/20161005/NEWS/161009807 |archive-date=December 9, 2016 |access-date=February 2, 2017 |ref=harv |deadurl=no}}</ref> It began in 1999 as a result of a popular component of a temporary exhibition and has grown to consist of a website, six regional pocket guides, and mobile apps that allow consumers to check the [[sustainability]] ratings of specific fisheries. The program has expanded to include business collaborations, local and national restaurant and grocer partnerships, and outreach partnerships—primarily other public aquariums and zoos. Large-scale business and grocer affiliations include [[Aramark]], [[Compass Group]], [[Target Corporation|Target]], and [[Whole Foods Market]].<ref name="bundle_seafoodpartners" /> In both 2009 and 2015, Seafood Watch was reportedly playing an influential role in the development of sustainable business practices within the global [[fishing industry]].<ref>{{harvnb|Parsons|2015}}; {{harvnb|Reynolds|2009}}.</ref> According to the aquarium, the program's efficacy is driven by its work with both businesses and consumers, and is supported by the aquarium's expanding science and ocean policy programs.{{sfn|Spring|2018|pp=159, 161–162}} |

||

By 2014, fifteen years after its inception, |

In the late-2000s, Seafood Watch was likely the most known and most widely distributed sustainable seafood guide out of around 200 internationally.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Roheim |first=Cathy A. |date=2009 |title=An Evaluation of Sustainable Seafood Guides: Implications for Environmental Groups and the Seafood Industry |url=http://cels.uri.edu/urissi/docs/08%20ROHEIM%20THAL%2024-3.pdf |journal=Marine Resource Economics |volume=24 |pages=301–302}}</ref> By 2014, fifteen years after its inception, the program had produced more than 52 million printed pocket guides. Its mobile apps were downloaded over one million times between 2009 and 2015.{{sfn|Parsons|2015}} In 2003, the program's website was granted a MUSE Award from the [[American Alliance of Museums]] for use of media and technology in science. [[Bon Appétit|''Bon Appétit'' magazine]] awarded its Tastemaker of the Year award to Seafood Watch in 2008 and, in 2013, [[Sunset (magazine)|''Sunset'' magazine]] described it as one of "the most effective consumer-awareness programs".<ref name="bundle_seafoodawards" /> |

||

In September 2016, the [[United States Agency for International Development]] announced it was cooperating with the aquarium to improve [[fisheries management]] in the [[Asia-Pacific]].<ref name="usaid_2016">{{cite web |url=https://2012-2017.usaid.gov/news-information/press-releases/sep-12-2016-usaid-partners-monterey-bay-aquarium-combat-illegal-fishing |title=USAID Partners with Monterey Bay Aquarium to Combat Illegal Fishing and Promote Sustainable Fisheries in Southeast Asia |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |date=September 12, 2016 |publisher=[[United States Agency for International Development]] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160925002942/http://www.usaid.gov/news-information/press-releases/sep-12-2016-usaid-partners-monterey-bay-aquarium-combat-illegal-fishing |archive-date=September 25, 2016 |access-date=February 2, 2017 |deadurl=no}}</ref> |

In September 2016, the [[United States Agency for International Development]] announced it was cooperating with the aquarium to improve [[fisheries management]] in the [[Asia-Pacific]].<ref name="usaid_2016">{{cite web |url=https://2012-2017.usaid.gov/news-information/press-releases/sep-12-2016-usaid-partners-monterey-bay-aquarium-combat-illegal-fishing |title=USAID Partners with Monterey Bay Aquarium to Combat Illegal Fishing and Promote Sustainable Fisheries in Southeast Asia |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |date=September 12, 2016 |publisher=[[United States Agency for International Development]] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160925002942/http://www.usaid.gov/news-information/press-releases/sep-12-2016-usaid-partners-monterey-bay-aquarium-combat-illegal-fishing |archive-date=September 25, 2016 |access-date=February 2, 2017 |deadurl=no}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 23:22, 28 March 2018

| Monterey Bay Aquarium | |

|---|---|

giant kelp | |

Main entrance in 2016 | |

| |

| 36°37′06″N 121°54′05″W / 36.618253°N 121.901481°W | |

| Slogan | To inspire conservation of the oceans[2] |

| Date opened | October 20, 1984 |

| Location | Cannery Row, Monterey, California |

| Floor space | 322,000 square feet (29,900 square meters)[1] |

| No. of animals | 35,000 |

| No. of species | more than 550 |

| Volume of largest tank | 1.2 million U.S. gallons (4.5 million liters) |

| Total volume of tanks | 2.3 million U.S. gallons (8.7 million liters) |

| Annual visitors | 2 million |

| Memberships | Association of Zoos and Aquariums[3] |

| Major exhibits | Kelp Forest, Sea Otters, Jellies, Open Sea |

| Public transit access | Monterey–Salinas Transit |

| Website | montereybayaquarium.org |

Monterey Bay Aquarium is a

Proposals to build a public aquarium in

Around two million people visit the aquarium each year, totaling more than 50 million through 2016. As a tourist destination, Monterey Bay Aquarium produces hundreds of millions of dollars for the economy of Monterey County, which has led to the revitalization of

History and facility

Three separate proposals for aquariums in

The aquarium is known for its regional focus on Monterey Bay and its display of marine life communities. While public aquariums at the time typically exhibited individual species, the work of marine biologist Ed Ricketts inspired an ecological approach to the layout of Monterey Bay Aquarium's original facility.[9] EHDD, the aquarium's architectural firm, was awarded a National Honor Award from the American Institute of Architects in 1988 for the design of the original facility.[10] The institute's state chapter in California gave the aquarium its Twenty-five Year Award in 2011[11] and, in 2016, Monterey Bay Aquarium was awarded the institute's national Twenty-five Year Award, described as "a benchmark and role model for aquariums everywhere."[1]

In 1996, the aquarium opened a second wing of aquarium exhibits called the Outer Bay that focuses on the pelagic habitat 60 miles (97 km) offshore of Monterey Bay. Costing US$57 million and taking seven years to develop, the wing almost doubled the aquarium’s public exhibit space.[13][14] A US$19 million renovation in 2011 added components to the wing and its name was changed to the Open Sea.[15] Other smaller additions and modifications have been made to the aquarium's facility.[16][17] Since the late‑1980s, the aquarium has also developed numerous temporary exhibitions.

Monterey Bay Aquarium developed a program in 1999 that provides consumers eating seafood the ability to choose species based on the sustainability rating of each fishery. This program has continued to evolve and has placed the aquarium in an influential position, impacting both fisheries management and the public discussion regarding seafood sustainability.[18] In discussing the aquarium's conservation and education programs, its track record for entertaining visitors, and its reputation for collaboration, the head of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums described the aquarium as "a definite leader".[19]

Aquarium exhibits

Monterey Bay Aquarium displays 35,000 animals belonging to over 550 species in 2.3 million U.S. gallons (8,700,000 L) of water.

In 2014, the aquarium stated that it takes no official position on the controversy of

Kelp Forest exhibit

At 28 feet (8.5 m) tall and 65 feet (20 m) long, the Kelp Forest exhibit is the focal point of Monterey Bay Aquarium's Ocean's Edge wing.

Open Sea wing

Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Open Sea wing consists of three separate galleries: various

Holding 1.2 million US gallons (4,500,000 L), the wing's Open Sea community exhibit is the aquarium's largest tank.

A 10-month, US$19 million renovation of the wing concluded in July 2011 to refurbish the Open Sea community exhibit. Turbulent swimming patterns of 300-pound (140 kg) tunas were dismantling the exhibit's structural glass tiles, which the sea turtles were subsequently eating, so the exhibit was drained after all 10,000 animals were caught. Supplemental exhibits were added as part of this renovation featuring artwork that highlights current issues in

Other permanent exhibits

In 2014, the aquarium had almost 200 exhibits with live animals organized into various galleries. Monterey Bay Aquarium was the first public aquarium to have its interior mapped on Google Street View, creating a virtual walking tour.[38]

-

Aplumose anemones in a 90-foot-long (27 m)[6]exhibit on the habitats of Monterey Bay.

-

Plumose anemones, abat star, sponges, and other cold-water invertebrates native to Monterey Bay

-

Localshorebird species in the aviary

-

Pacific coral reef community containing living corals

-

African penguins on exhibit

-

A circular exhibit at the entrance to the Open Sea wing contains schooling Pacific sardines.

-

An exhibit demonstrates the streamlined bodies of Pacific mackerel.

-

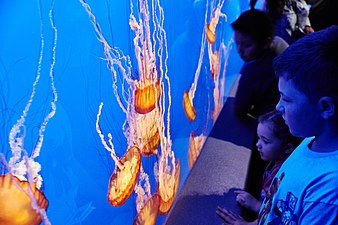

Pacific sea nettles in a long kreisel tank

Temporary exhibitions

Monterey Bay Aquarium began creating temporary exhibitions (or "special exhibitions") in order to display animals that are found outside of Monterey Bay. The first of these, titled "Mexico's Secret Sea", focused on the

At least three exhibitions have been devoted entirely to displaying jellyfish. In 1989, the aquarium's second temporary exhibition, titled "Living Treasures of the Pacific", included three

Research and conservation

Monterey Bay Aquarium helped create momentum for the establishment of the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary in 1992, one of the largest marine protected areas in the United States.[48] In 2004, the aquarium created a formal division to become involved in United States ocean policy and law, working with the Pew Charitable Trusts and the United States Commission on Ocean Policy at the onset.[49] Aquarium researchers have authored scientific publications involving sea otters, great white sharks, and bluefin tunas, which are important species in the northern Pacific Ocean.[43][50] In addition to other animals,[51][52] the aquarium has published work in the areas of veterinary medicine,[53] visitor studies, and museum exhibition development.[54][55][56]

The Association of Zoos and Aquariums has awarded the aquarium with two awards for its efforts in propagating captive animals—including one for purple-striped jellies in 1992—and also its general conservation award for the aquarium’s Sea Otter Research and Conservation Program.[34] In October 2017, the aquarium received the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums' Conservation Award for its "commitment to ocean protection and public awareness".[57]

Marine life

Monterey Bay Aquarium's Sea Otter Research and Conservation program began in 1984 to research and

Pacific bluefin and yellowfin tunas have been historically displayed in the aquarium's Open Sea community exhibit, some reaching more than 300 pounds (140 kg). In 2011, three dozen fishes of the two species were on exhibit.[32] Prior to opening the Open Sea wing in 1996, the aquarium established the Tuna Research and Conservation Center in 1994 in partnership with Stanford University's Hopkins Marine Station. Aquarium researchers and Barbara Block—professor of marine sciences at Stanford University—have tagged wild Pacific bluefin tunas to study predator-prey relationships, and have also investigated tuna endothermy with captive tunas at the center.[63][64] To improve international collaboration of bluefin tuna management, Monterey Bay Aquarium and Stanford University hosted a symposium in January 2016 in Monterey. Over 200 scientists, fisheries managers, and policy makers gathered to discuss solutions to the decline of Pacific bluefin tuna populations.[65]

Great white sharks

In 1984, Monterey Bay Aquarium's first attempt to display a great white shark lasted 11 days, ending when the shark died because it did not eat.[73] Through a later program named Project White Shark, six white sharks were exhibited between 2004 and 2011 in the aquarium's Open Sea community exhibit,[48] which was constructed in the 1990s. Researchers at universities in California attributed the aquarium's success at exhibiting white sharks to the use of a 4-million-US-gallon (15,000,000 L) net pen, which gave the sharks time to recover from capture prior to transport. A 3,200-US-gallon (12,000 L) portable tank used to transport the fish to the aquarium allowed the sharks to continuously swim, which they must do in order to respire.[74] These endeavors led to the first instance of a white shark eating in an aquarium.[75]

At least one organization—the Pelagic Shark Research Foundation based in Santa Cruz, California—criticized the aquarium for attempting to keep white sharks in captivity, questioning the significance of possible scientific research and the ability to educate visitors.[76] However, several independent biologists expressed approval for Project White Shark because of its logistical design, educational impact, and scientific insights. Regarding its educational impact, a white shark researcher from Australia stated in 2006 that "the fact people can come and see these animals and learn from them is of immeasurable value."[77] The first captive white shark—on exhibit in 2004 for more than six months—was seen by one million visitors, and another million visitors saw either the second or third white sharks on display.[78] In 198 days, the first white shark grew more than 17 inches (43 cm) and gained over 100 pounds (45 kg) prior to its release.[79] As of 2016,[update] Monterey Bay Aquarium is the only public aquarium in the world to have successfully exhibited a white shark for longer than 16 days.[80]

The aquarium's attempts to display captive white sharks ended in 2011 due to the project's high resource intensity. Captive white sharks also incurred injuries and killed other animals in the exhibit after becoming increasingly aggressive,[81] and the final shark died due to unknown reasons immediately following its release.[82][73] Although no longer on exhibit for the public, aquarium scientists have continued to conduct research on white sharks. Collaborating with Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute in June 2016, aquarium scientists created cameras attached to harmless dorsal fin tags in an attempt to study the behavior of white sharks during their gathering known as the White Shark Café.[83][84]

Seafood program

Monterey Bay Aquarium’s consumer-based Seafood Watch program encourages sustainable seafood purchasing from fisheries that are "well managed and caught or farmed in ways that cause little harm to habitats or other wildlife."[85] It began in 1999 as a result of a popular component of a temporary exhibition and has grown to consist of a website, six regional pocket guides, and mobile apps that allow consumers to check the sustainability ratings of specific fisheries. The program has expanded to include business collaborations, local and national restaurant and grocer partnerships, and outreach partnerships—primarily other public aquariums and zoos. Large-scale business and grocer affiliations include Aramark, Compass Group, Target, and Whole Foods Market.[86] In both 2009 and 2015, Seafood Watch was reportedly playing an influential role in the development of sustainable business practices within the global fishing industry.[87] According to the aquarium, the program's efficacy is driven by its work with both businesses and consumers, and is supported by the aquarium's expanding science and ocean policy programs.[88]

In the late-2000s, Seafood Watch was likely the most known and most widely distributed sustainable seafood guide out of around 200 internationally.[89] By 2014, fifteen years after its inception, the program had produced more than 52 million printed pocket guides. Its mobile apps were downloaded over one million times between 2009 and 2015.[90] In 2003, the program's website was granted a MUSE Award from the American Alliance of Museums for use of media and technology in science. Bon Appétit magazine awarded its Tastemaker of the Year award to Seafood Watch in 2008 and, in 2013, Sunset magazine described it as one of "the most effective consumer-awareness programs".[91]

In September 2016, the

Political advocacy

Monterey Bay Aquarium plays an active role in federal and state politics, from sponsoring governmental legislation about the ocean

The aquarium is a founding partner of

Educational efforts

Each year approximately 75,000 students, teachers, and chaperones from California access Monterey Bay Aquarium for free. An additional 1,500 low-income students, 350 teenagers, and 1,200 teachers participate in structured educational programs throughout the year. Between 1984 and 2014, the aquarium hosted more than 2 million students.

A 13,000-square-foot (1,200-square-meter), US$30 million education center being developed by the aquarium is expected to open in 2018, and will double the number of students and teachers the aquarium is able to work with each year.

Community and economic influence

Monterey Bay Aquarium employed over 500 people and had 1,200 active volunteers in 2015.[111] Between 1984 and 2014, 8,500 volunteers donated 3.2 million community service hours to the aquarium.[48] The aquarium attracts around 2 million visitors each year and, through 2016, over 50 million people had visited. Out of the 51 accredited public aquariums in the United States in 2015, Monterey Bay Aquarium's 2.08 million visitors ranked it second by number of visits, behind Georgia Aquarium.[112] In 2015, the aquarium served 290,000 annual members.[108][1]

Free admission programs are offered for Monterey County residents including "Shelf to Shore", with the county's free library system, and "Free to Learn", with local nonprofit organizations and Monterey–Salinas Transit.[113][114] Additionally, the aquarium offers free admission to Monterey County residents during a weeklong event in December, which grew from almost 17,000 visitors in 1998 to 50,000 visitors in 2013. In 2014, the program was expanded to include neighboring Santa Cruz and San Benito counties.[115] An annual event called "Día del Niño" offers bilingual feeding presentations (in Spanish), activities, and free admission for children under the age of 13.[116] Between 2002 and 2014, over 700,000 people visited the aquarium for free through its outreach programs.[117]

In 2013, the aquarium’s operational spending and its 2 million visitors generated US$263 million to the economy of Monterey County.[111] In August 2016, an evening event at Monterey Bay Aquarium raised over US$110,000 for the Community Foundation for Monterey County’s drive to provide relief for the Soberanes Fire.[118]

In media and popular culture

Monterey Bay Aquarium has been featured in two documentaries on

After comparing the aquarium's visitor feedback to the feedback of other attractions, the media and the travel industry have awarded the aquarium with top accolades. In 2014,

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ The Hovden Cannery closed in 1973, but a large exhibit in the aquarium displays the cannery's original boilers.[5]

- ^ The Open Sea community exhibit's 54-foot (16 m) long and 14.5-foot (4.4 m) tall viewing window was reportedly the largest aquarium window in the world when it was installed in 1996.[13]

- ^ In 2009, the jellyfish expert at the aquarium expected "three good stings" every week.[22]

References

- ^ a b c d Gerfen 2016.

- ^ a b Brincks 2009.

- ^ "Currently Accredited Zoos and Aquariums". Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ Jaret 2011.

- ^ Duggan 2013.

- ^ a b Lokken 1985.

- ^ Brincks 2009; Perlman 2004.

- ^ McNulty 1989; Ortiz, Catalina (November 20, 1994). "A Beauty by the Bay : Science: 17 million visitors have made the Monterey Bay Aquarium the nation's most popular". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 8, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Thomas 2014; Cooper 2014 and Pridmore 1991; Ryce, Walter (June 2, 2016). "A Monterey Bay Aquarium founder asks, What would Steinbeck and Ricketts say?". Monterey County Weekly. Seaside, California. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

- ^ "2016 Twenty-five Year Award" 2016; "Honor Awards 1980 – 1989". The American Institute of Architects. 2008. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The American Institute of Architects, California Council, Announces Monterey Bay Aquarium as the 2011 Twenty-Five Year Award Recipient". The American Institute of Architects California Council. October 19, 2011. Archived from the original on July 1, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "2016 Twenty-five Year Award" 2016.

- ^ a b c McCabe 1996.

- ^ Dornin, Rusty (January 28, 1996). "Aquarium's new exhibit offers rare glimpse into the ocean deep". CNN. Archived from the original on February 2, 1999. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Taylor, Dennis (June 24, 2011). "Monterey Bay Aquarium's $19M renovation unveiled". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Archived from the original on June 28, 2017. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Rudolph and Sletten Completes Renovation of Monterey Bay Aquarium, Adds Skywalk and 8,000 Square Feet of Space". Business Wire. July 13, 2004. Archived from the original on September 27, 2017. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Yollin, Patricia (March 14, 2008). "New look for Monterey Aquarium Splash Zone". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Parsons 2015; Reynolds 2009: "with its advice on what seafoods consumers should eat and chefs should serve, the aquarium has taken an influential role in the debate over sustainable fishing practices."

- ^ Reynolds 2009: "'They are a definite leader,' says Kristin Vehrs, executive director of the Maryland-based Assn. of Zoos & Aquariums, which accredits aquariums. 'They do a great job of balancing the crowd-pleasing with the rigor of the education and conservation programs. They've also been good at sharing' expertise with other institutions."

- ^ Watanabe & Phillips 1985.

- ^ Animal counts and water volume:

- Animal count: Beadle & Thompson 2015

- Species count: Jaret 2011

- Total water volume: Kingsley, Eric; Phillips, Roger; Mansergh, Sarah (August 24–27, 2008). "Ozone Use at the Monterey Bay Aquarium: A Natural Seawater Facility" (PDF). Orlando, Florida: Proceedings of the International Ozone Association – Pan American Group. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 11, 2016. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

- ^ a b c d Reynolds 2009.

- ^ "Oceans in Glass" 2006: events occur at 12:17 and 13:48.

- ^ Mintchell, Gary A. (November 1, 2000). "Monterey Bay Aquarium reels in the perfect automation solution". Consulting–Specifying Engineer. Archived from the original on October 18, 2017. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Thomas 2014; "Life on the Bay at the Monterey Bay Aquarium". Monterey Bay Aquarium Foundation. Archived from the original on July 29, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Thomas 2014; Watanabe & Phillips 1985.

- ^ Lokken 1985; Pridmore 1991; Brincks 2009; Dickey, Gwyneth (September 29, 2009). "Kelp forest gets first-class stamp". The Monterey County Herald. Archived from the original on September 21, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Oceans in Glass" 2006 (at 9:45): "This is a living kelp forest, and its creation flew in the face of professionals who thought it was a losing bet. Nobody had ever successfully grown kelp on this scale, but there were also more pressing concerns. The exhibit was intended to recreate a key habitat of the Monterey Bay, and critics scoffed that nobody would be interested. The public rendered its verdict quickly: they were enthralled."

- ^ "Oceans in Glass" 2006: event occurs at 10:41.

- ^ Pridmore 1991; Watanabe & Phillips 1985.

- ^ a b Cooper 2011.

- ^ a b c d Rogers 2011a.

- ^ McCabe 1996: "The aquarium holds the largest permanent collection of jellyfish species in the United States and displays more of them than does any other facility in the world."

- ^ a b c AZA award pages:

- "About the Exhibit Award". Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Archived from the original on May 4, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Propagation: "About the Edward H. Bean Award". Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Archived from the original on September 26, 2016. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "About the North American Conservation Award". Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "About the Education Award". Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Archived from the original on January 28, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "About the Angela Peterson Excellence in Diversity Award". Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Archived from the original on September 15, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

- "About the Exhibit Award". Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Archived from the original on May 4, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ Miller, Steven H. (October 2013). "Monterey Bay Aquarium: New Digitally-Fabricated Aquarium Tank Liner Can Stand the Test of the Giant Tuna" (PDF). Waterproof!. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2016. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

{{cite magazine}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rogers 2011a; Lebourgeois, Benoit (July 28, 2011). "Monterey Bay Aquarium's 'Open Sea' focuses on migrations". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 13, 2015. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rogers 2011b; Squatriglia 2006; Reynolds 2009.

- ^ "Aquarium galleries now on Google Maps Street View". The Salinas Californian. May 21, 2014. Archived from the original on January 20, 2018. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ McNulty 1989.

- ^ "Monterey Delves Into 'Mysteries of the Deep'". Los Angeles Times. March 14, 1999. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Other temporary exhibitions:

- "More to sharks than 'Jaws' at Monterey Bay Museym". The Augusta Chronicle. March 28, 2004. Archived from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Yollin, Patricia (March 30, 2007). "MONTEREY / They're otter(ly) irresistible / Playful mammals' fans thrilled by new exhibit at aquarium". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Yollin, Patricia (April 10, 2009). "Sea horse fun facts Sea horses bump jellyfish at Monterey aquarium". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

- "More to sharks than 'Jaws' at Monterey Bay Museym". The Augusta Chronicle. March 28, 2004. Archived from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- ^ a b Tentacles temporary exhibition:

- Anderson, Mark (April 10, 2014). "Superhero squid, plus giant octopi, stumpy cuttlefish and the wunderpus, all at the Aquarium's new Tentacles". Monterey County Weekly. Seaside, California. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Yollin, Patricia (May 15, 2014). "Mysterious creatures of Monterey Bay Aquarium's 'Tentacles'". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Nordstrand, Dave (April 11, 2014). "Aquarium opens 'Tentacles'". The Salinas Californian. Archived from the original on October 19, 2016. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

- Anderson, Mark (April 10, 2014). "Superhero squid, plus giant octopi, stumpy cuttlefish and the wunderpus, all at the Aquarium's new Tentacles". Monterey County Weekly. Seaside, California. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- ^ a b Spring 2018, p. 159.

- ^ Phillips, Ari (December 11, 2013). "Why Aquariums Are Obsessed With Climate Change". ThinkProgress. Archived from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - .

- ^ Yollin, Patricia (April 11, 2016). "Monterey Bay Aquarium Takes a Deep Dive Into Baja California". KQED. Archived from the original on April 12, 2016. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Yollin 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Cooper 2014.

- ^ a b Spring 2018, p. 160.

- ^ Lists of aquarium research publications:

- "Sea Otter Publications" (PDF). Monterey Bay Aquarium Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 29, 2016. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Shark Publications" (PDF). Monterey Bay Aquarium Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 29, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Tuna Publications" (PDF). Monterey Bay Aquarium Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 29, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

- "Sea Otter Publications" (PDF). Monterey Bay Aquarium Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 29, 2016. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ISSN 1448-6059.

- ISSN 1469-7769.

- ^ Murray, Michael J. (2002). "Fish Surgery" (PDF). Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine. 11 (4): 246–257 – via Amazon Web Services.

- ISSN 2151-6952.

- ^ Rand, Judy (1990). Fish Stories that Hook Readers: Interpretive Graphics at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Jacksonville, Alabama: Center for Social Design.

- ISSN 2151-6952.

- ^ "Monterey Bay Aquarium to receive Conservation Award". World Association of Zoos and Aquariums. September 14, 2017. Archived from the original on October 22, 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sea otter rehabilitation:

- Graff, Amy (October 26, 2017). "Otter returns to wild as Marine Mammal Center ramps up efforts to heal endangered species". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on November 2, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Dixon, Laura (March 3, 2012). "Historic Monterey Bay Aquarium Sea Otter Dies". NBC Bay Area. San Jose, California. Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Coles, Jeremy (June 20, 2017). "Conservation success for otters on the brink". BBC Earth. Archived from the original on July 17, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

- Graff, Amy (October 26, 2017). "Otter returns to wild as Marine Mammal Center ramps up efforts to heal endangered species". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on November 2, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ a b PBS Nature documentaries featuring the aquarium:

- "Oceans in Glass: Behind the Scenes of the Monterey Bay Aquarium – Introduction". PBS. June 20, 2011. Archived from the original on December 30, 2014. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Saving Otter 501 – About". PBS. Archived from the original on April 4, 2016. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

- "Oceans in Glass: Behind the Scenes of the Monterey Bay Aquarium – Introduction". PBS. June 20, 2011. Archived from the original on December 30, 2014. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- ^ Mariana, Barrera (August 8, 2013). "Monterey Bay: Biologists release tiny snowy plovers into the wild". The Monterey County Herald. Archived from the original on January 23, 2018. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Penguin hatches at Monterey Bay Aquarium". The Salinas Californian. June 11, 2014. Archived from the original on October 10, 2016. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Yollin, Patricia (June 21, 2007). "MONTEREY / The teaching albatross / Aquarium visitors learn about the dangers of plastics to ocean birds". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Research efforts with the bluefin tuna:

- Carey, Bjorn (September 25, 2015). "Stanford scientists help discover Pacific bluefin tunas' favorite feeding spots". Stanford University. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Martin, Allen (February 23, 2015). "West Coast Scientists Fishing For Solutions To Bluefin Tuna Overfishing". KPIX-TV. CBS. Archived from the original on April 1, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Fears, Darryl (March 24, 2014). "Deepwater Horizon oil left tuna, other species with heart defects likely to prove fatal". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 7, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

- Carey, Bjorn (September 25, 2015). "Stanford scientists help discover Pacific bluefin tunas' favorite feeding spots". Stanford University. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ "Oceans in Glass" 2006: event occurs at 41:20.

- ^ Bluefin Futures Symposium, January 2016:

- Rosato, Joe (January 21, 2016). "Bluefin Tuna, Once Bountiful, Now in Peril". NBC Bay Area. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Damanaki, Maria (January 26, 2016). "A Bluefin Tuna for $118,000: Going, Going … Gone?". National Geographic Voices. Archived from the original on August 30, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

- Rosato, Joe (January 21, 2016). "Bluefin Tuna, Once Bountiful, Now in Peril". NBC Bay Area. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ McCabe 1996; "Oceans in Glass" 2006 (at 5:23): "The jelly collection at the aquarium is the largest in the world."

- ^ Yollin 2012: "The Monterey Bay Aquarium pioneered the display of jellyfish in North America and spawned a trend of jelly exhibits around the United States."

- ^ Reynolds 2009: "... and it has pioneered the display of jellyfish and ..."

- . Retrieved October 23, 2016.

- ^ Yin 2016.

- ^ Forgione, Mary (March 25, 2014). "Monterey Bay: These cuttlefish, octopus star in aquarium's new show". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Public gets first view of a live vampire squid and other deep-sea cephalopods". Phys.org. Science X. June 9, 2014. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Hopkins 2016.

- ^ Squatriglia 2006; Rogers 2011b.

- ^ "Oceans in Glass" 2006: event occurs at 24:21.

- ^ Speizer, Irwin; Cone, Marla (March 14, 2005). "Captive great white kills 2 sharks". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on March 21, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Squatriglia 2006.

- ^ Stienstra, Tom (August 31, 2008). "Aquarium shark sighting lets fish lovers refocus their fears". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Oceans in Glass" 2006: event occurs at 49:40.

- ^ Fong & Lee 2016; Reynolds 2009; Squatriglia 2006; Squatriglia, Chuck (January 17, 2007). "MONTEREY / More room to grow / Aquarium lets young white shark go after 137 days in captivity". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on November 23, 2016. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Fong & Lee 2016; Squatriglia 2006.

- ^ Forgione, Mary (November 3, 2011). "Great white shark dies after release from Monterey Bay Aquarium". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 4, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Becker, Rachel (July 2, 2016). "New Camera Tag to Help Solve Great White Mystery". Slate. Archived from the original on August 30, 2016. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

{{cite magazine}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Monterey researchers hope to solve great white shark mystery". KSBW. June 29, 2016. Archived from the original on October 14, 2016. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hiolski, Emma (October 5, 2016). "Carmel woman to be honored by White House". The Monterey County Herald. Archived from the original on December 9, 2016. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Seafood Watch business partnerships:

- "Aramark Reports Progress on Sustainable Seafood Sourcing Goals". Business Wire. October 12, 2017. Archived from the original on October 12, 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Stabley, Susan (July 5, 2010). "Eat locally, impact globally: Compass Group uses purchasing power for change". Charlotte Business Journal. Archived from the original on July 7, 2010. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Ayque, Jamie (September 22, 2016). "Target to Offer Only Sustainable Seafood in Stores, One Big Step in Saving the Ocean". Nature World News. Archived from the original on September 23, 2016. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Whole Foods Market® to Open Newest Store in University Place on May 7". Puget Sound Business Journal. Seattle, Washington. May 6, 2015. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); "Small New Zealand Fishing Town Makes a Big Splash in U.S. Marketplace". The Business Journals. August 10, 2016. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

- "Aramark Reports Progress on Sustainable Seafood Sourcing Goals". Business Wire. October 12, 2017. Archived from the original on October 12, 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- ^ Parsons 2015; Reynolds 2009.

- ^ Spring 2018, pp. 159, 161–162.

- ^ Roheim, Cathy A. (2009). "An Evaluation of Sustainable Seafood Guides: Implications for Environmental Groups and the Seafood Industry" (PDF). Marine Resource Economics. 24: 301–302.

- ^ Parsons 2015.

- ^ Awards received by Seafood Watch:

- "2003 Muse Award Winners". American Alliance of Museums. Archived from the original on September 15, 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Monterey Bay Aquarium Wins Tastemaker Award from Bon Appetit Magazine for Its influential Seafood Watch Program". PR Newswire. September 5, 2008. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Sunset: Fish 2013

- "2003 Muse Award Winners". American Alliance of Museums. Archived from the original on September 15, 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ "USAID Partners with Monterey Bay Aquarium to Combat Illegal Fishing and Promote Sustainable Fisheries in Southeast Asia". United States Agency for International Development. September 12, 2016. Archived from the original on September 25, 2016. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "AB 2139 Assembly Bill – Bill Analysis". Legislative Counsel Bureau (California State Legislature). June 20, 2016. Archived from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Fish 2013.

- ^ Spring 2018, p. 164.

- ^ Support of California Proposition 67 (2016):

- "California Proposition 67, Plastic Bag Ban Veto Referendum (2016)". Ballotpedia. Archived from the original on July 10, 2017. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "I'm voting YES on Proposition 67 for a plastic-free ocean!". Monterey Bay Aquarium Foundation. Archived from the original on October 7, 2016. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "What's the deal with plastic pollution?". Monterey Bay Aquarium Foundation. October 11, 2016. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

- "California Proposition 67, Plastic Bag Ban Veto Referendum (2016)". Ballotpedia. Archived from the original on July 10, 2017. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- ^ "2016 Global Ocean Science Education Workshop" (PDF). The College of Exploration. June 13–15, 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 12, 2017. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rogers, Paul (July 10, 2017). "Plastic to be phased out at major American aquariums". The Mercury News. San Jose, California. Archived from the original on November 2, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Spring 2018, pp. 162–163.

- ^ "Center for Ocean Solutions". Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Jordan, Rob (December 20, 2016). "Unexamined risks from tar sands oil may threaten oceans". Stanford University. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Statement of The Monterey Bay Aquarium to the United Nations Ocean Conference" (PDF). Division for Sustainable Development. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. June 9, 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 25, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Spring, Margaret (February 16, 2017). "Statement of the Monterey Bay Aquarium: UN SDG 14 Preparatory Conference, New York" (PDF). Division for Sustainable Development. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 5, 2017. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Wessel, Lindzi (March 15, 2017). "Updated: Some 100 groups have now endorsed the March for Science". Science. Archived from the original on December 11, 2017. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Seipel, Brooke (April 22, 2017). "Penguins hold their own Science March of the Penguins". The Hill. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on July 9, 2017. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Spring 2018, p. 158.

- ^ Mayberry 2016.

- ^ a b c Stock 2015.

- ^ "Monterey Bay Aquarium The Webby Awards". The Webby Awards. International Academy of Digital Arts and Sciences. 2000. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Duggan 2013: "The area went into decline until the 1984 opening of the Monterey Bay Aquarium, which brought new life to Cannery Row."

- ^ a b Beadle & Thompson 2015.

- ^ Abel, David (August 2, 2016). "Top aquariums in the US, in terms of visitors". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on October 13, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Shelf-to-Shore Aquarium Pass Program". Monterey County Free Libraries. April 28, 2017. Archived from the original on August 28, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "MST-Aquarium program going swimmingly". The Salinas Californian. April 5, 2015. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Villa, Juan (December 5, 2014). "Monterey Bay Aquarium: Making waves for 30 years". The Salinas Californian. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Monterey Bay Aquarium sets Día del Niño for April 26". The Salinas Californian. April 6, 2015. Archived from the original on January 18, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Klein, Kerry (December 5, 2014). "Aquarium's outreach programs make a splash". The Salinas Californian. Archived from the original on March 28, 2018. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Truskot, Joe (August 8, 2016). "Fire benefits on Sunday bring in nearly $180,000". The Salinas Californian. Archived from the original on August 11, 2016. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Big Blue Live television program:

- "Big Blue Live – Our Partners". BBC. Archived from the original on August 25, 2015. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Television | Live Event in 2016". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. 2016. Archived from the original on August 3, 2016. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

- "Big Blue Live – Our Partners". BBC. Archived from the original on August 25, 2015. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- ^ Nimoy, Leonard; William Shatner (March 4, 2003). Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, Special Collector's Edition: Audio commentary (DVD, disc 1/2). Paramount Pictures.

- ^ "A look at Pixar's real life inspiration for 'Finding Dory'". CBS News. June 18, 2016. Archived from the original on August 21, 2016. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Fernandes, Marriska (July 31, 2017). "A tour of HBO's Big Little Lies filming locations in Monterey". Tribute. Toronto, Ontario. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved October 17, 2017.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Thompson, Chuck (August 13, 2014). "And the world's best zoo is ..." CNN. Archived from the original on August 4, 2016. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Trejos, Nancy (July 15, 2015). "TripAdvisor: Best amusement parks, zoos and aquariums". USA Today. Archived from the original on September 18, 2015. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Pfaff, Leslie Garisto (April 2015). "The FamilyFun Travel Awards". Parents. Archived from the original on November 19, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

{{cite magazine}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Monterey Bay Aquarium". Frommer's. Archived from the original on March 22, 2018. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

Sources

- "2016 Twenty-five Year Award". The American Institute of Architects. 2016. Archived from the original on January 17, 2016. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Beadle, Philip; Thompson, Vicki (April 20, 2015). "Exclusive: Monterey Bay Aquarium topped 2M visitors in 2014 — here's how the staff pulls it off (Photos)". Silicon Valley Business Journal. San Jose, California. Archived from the original on September 21, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Brincks, Renee (2009). "An Ocean of Excellence: The Monterey Bay Aquarium Celebrates its Silver Anniversary". Carmel Magazine. Carmel-by-the-Sea, California. Archived from the original on June 9, 2016. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Cooper, Jeanne (June 21, 2011). "8 don't-miss creatures at the Monterey Bay Aquarium". SFGate. Hearst Communications. Archived from the original on September 26, 2016. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Cooper, Leigh (December 5, 2014). "Monterey Bay Aquarium's top 10 legacies, so far". The Salinas Californian. Archived from the original on January 18, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Duggan, Tara (September 16, 2013). "Cannery Row offers hints of its history". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Fish, Peter (July 2013). "Monterey Bay's ecological renaissance". Sunset. Oakland, California. Archived from the original on September 30, 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Fong, Joss; Lee, Dion (July 8, 2016). "Why there aren't any great white sharks in captivity". Vox. Archived from the original on July 10, 2016. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Gerfen, Katie (January 15, 2016). "The Monterey Bay Aquarium Wins the 2016 AIA Twenty-Five Year Award". Architect. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on August 16, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Hopkins, Christopher Dean (January 8, 2016). "Great White Shark Dies After Just 3 Days In Captivity At Japan Aquarium". NPR. Archived from the original on April 3, 2017. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Jaret, Peter (March 1, 2011). "Monterey Peninsula: Monterey Bay Aquarium an idea ahead of its time". Via. Oakland, California. Archived from the original on September 23, 2016. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Lokken, Dean (August 25, 1985). "Monterey Bay Aquarium Awash in a Tide of Visitors". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 21, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Mayberry, Carly (February 19, 2016). "Plans for Monterey Bay Aquarium's new $30 million education center underway". The Monterey County Herald. Archived from the original on February 20, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - McCabe, Michael (February 18, 1996). "Monterey Aquarium Goes Really Deep / Vast new wing will display sea creatures never before held in captivity". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - McNulty, Jennifer (April 30, 1989). "Monterey Bay Aquarium Gives Visitors a Thrill". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 17, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Oceans in Glass: Behind the Scenes of the Monterey Bay Aquarium" (Documentary film). PBS. January 22, 2006.

- Parsons, Russ (May 13, 2015). "Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch turns 15". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 20, 2016. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Perlman, David (October 18, 2004). "A celebration of the ocean / Monterey Bay Aquarium's mission to 'inspire, engage, empower' marks 20th year". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Pridmore, Jay (August 4, 1991). "Living Museum: Monterey Aquarium Focuses On Its Nearby Waters". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Reynolds, Christopher (October 18, 2009). "Holy mackerel, that's a great white!". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 29, 2014. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Rogers, Paul (June 27, 2011). "Big tank at Monterey Bay Aquarium gets major face lift". The Mercury News. San Jose, California. Archived from the original on September 23, 2016. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Rogers, Paul (September 1, 2011). "New great white shark goes on display at Monterey Bay Aquarium". The Mercury News. San Jose, California. Archived from the original on September 26, 2016. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Spring, Margaret (2018). "Lessons from thirty-one years at the Monterey Bay Aquarium and reflections on aquariums' expanding role in conservation action". In Minteer, Ben A.; Maienschein, Jane; Collins, James P. (eds.). The ark and beyond: the evolution of zoo and aquarium conservation. University of Chicago Press. pp. 156–168. )

- Squatriglia, Chuck (October 8, 2006). "Aquarium's habitat for a heavyweight / Monterey Bay creates a home for second voracious – but delicate – great white". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on November 23, 2016. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Stock, Lynn Peithman (November 6, 2015). "2015 Community Impact Award Winner: Monterey Bay Aquarium". Silicon Valley Business Journal. San Jose, California. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thomas, Sandra (April 17, 2014). "Monterey Bay makes splash as captive-free model". Vancouver Courier. Archived from the original on April 20, 2014. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Watanabe, JM; Phillips, RE (1985). Establishing a captive kelp forest: Developments during the first year at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. American Academy of Underwater Sciences. p. 11. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

{{cite conference}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Yin, Steph (August 11, 2016). "Growing Comb Jellies in the Lab Like Sea-Monkeys". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 26, 2016. Retrieved October 23, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Yollin, Patricia (April 1, 2012). "Monterey aquarium jellies jam to psychedelic beat". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

External links

- Official website

- Walkthrough of aquarium on Google Street View

- Aquarium's blog detailing conservation and science efforts

- YouTube video on the history of the aquarium from a founding biologist