Veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a

Some vetoes can be overcome, often by a supermajority vote: in the United States, a two-thirds vote of the House and Senate can override a presidential veto.[1] Some vetoes, however, are absolute and cannot be overridden. For example, in the United Nations Security Council, the five permanent members (China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States) have an absolute veto over any Security Council resolution.

In many cases, the veto power can only be used to prevent changes to the status quo. But some veto powers also include the ability to make or propose changes. For example, the

The executive power to veto legislation is one of the main tools that the executive has in the

The word "veto" comes from the Latin for "I forbid". The concept of a veto originated with the Roman offices of consul and tribune of the plebs. There were two consuls every year; either consul could block military or civil action by the other. The tribunes had the power to unilaterally block any action by a Roman magistrate or the decrees passed by the Roman Senate.[6]

History

Roman veto

The institution of the veto, known to the Romans as the intercessio, was adopted by the Roman Republic in the 6th century BC to enable the tribunes to protect the mandamus interests of the plebeians (common citizenry) from the encroachments of the patricians, who dominated the Senate. A tribune's veto did not prevent the senate from passing a bill but meant that it was denied the force of law. The tribunes could also use the veto to prevent a bill from being brought before the plebeian assembly. The consuls also had the power of veto, as decision-making generally required the assent of both consuls. If they disagreed, either could invoke the intercessio to block the action of the other. The veto was an essential component of the Roman conception of power being wielded not only to manage state affairs but to moderate and restrict the power of the state's high officials and institutions.[6]

A notable use of the Roman veto occurred in the Gracchan land reform, which was initially spearheaded by the tribune Tiberius Gracchus in 133 BC. When Gracchus' fellow tribune Marcus Octavius vetoed the reform, the Assembly voted to remove him on the theory that a tribune must represent the interests of the plebeians. Later, senators outraged by the reform murdered Gracchus and several supporters, setting off a period of internal political violence in Rome.[7]

Liberum veto

In the constitution of the

Emergence of modern vetoes

The modern executive veto derives from the European institution of

Following the

The presidential veto was conceived in by republicans in the 18th and 19th centuries as a counter-majoritarian tool, limiting the power of a legislative majority.[12] Some republican thinkers such as Thomas Jefferson, however, argued for eliminating the veto power entirely as a relic of monarchy.[13] To avoid giving the president too much power, most early presidential vetoes, such as the veto power in the United States, were qualified vetoes that the legislature could override.[13] But this was not always the case: the Chilean constitution of 1833, for example, gave that country's president an absolute veto.[13]

Types

Most modern vetoes are intended as a check on the power of the government, or a

Other types of veto power, however, have safeguarded other interests. The denial of

Vetoes may be classified by whether the vetoed body can override them, and if so, how. An absolute veto cannot be overridden at all. A qualified veto can be overridden by a supermajority, such as two-thirds or three-fifths. A suspensory veto, also called a suspensive veto, can be overridden by a simple majority, and thus serves only to delay the law from coming into force.[17]

Types of executive vetoes

A package veto, also called a "block veto" or "full veto", vetoes a

Some veto powers are limited to budgetary matters (as with line-item vetoes in some US states, or the financial veto in New Zealand).[18] Other veto powers (such as in Finland) apply only to non-budgetary matters; some (such as in South Africa) apply only to constitutional matters. A veto power that is not limited in this way is known as a "policy veto".[3]

One type of budgetary veto, the reduction veto, which is found in several US states, gives the executive the authority to reduce budgetary appropriations that the legislature has made.[18] When an executive is given multiple different veto powers, the procedures for overriding them may differ. For example, in the US state of Illinois, if the legislature takes no action on a reduction veto, the reduction simply becomes law, while if the legislature takes no action on an amendatory veto, the bill dies.[19]

A pocket veto is a veto that takes effect simply by the executive or head of state taking no action. In the United States, the pocket veto can only be exercised near the end of a legislative session; if the deadline for presidential action passes during the legislative session, the bill will simply become law.[20] The legislature cannot override a pocket veto.[2]

Some veto powers are limited in their subject matter. A constitutional veto only allows the executive to veto bills that are

Legislative veto

A legislative veto is a veto power exercised by a legislative body. It may be a veto exercised by the legislature against an action of the executive branch, as in the case of the

Veto over candidates

In certain political systems, a particular body is able to exercise a veto over candidates for an elected office. This type of veto may also be referred to by the broader term "vetting".

Historically, certain European Catholic monarchs were able to veto candidates for the

In Iran, the Guardian Council has the power to approve or disapprove candidates, in addition to its veto power over legislation.

In China, following a pro-democracy landslide in the

Balance of powers

In presidential and semi-presidential systems, the veto is a legislative power of the presidency, because it involves the president in the process of making law. In contrast to proactive powers such as the

Executive veto powers are often ranked as comparatively "strong" or "weak". A veto power may be considered stronger or weaker depending on its scope, the time limits for exercising it and requirements for the vetoed body to override it. In general, the greater the majority required for an override, the stronger the veto.[3]

Partial vetoes are less vulnerable to override than package vetoes,[26] and political scientists who have studied the matter have generally considered partial vetoes to give the executive greater power than package vetoes.[27] However, empirical studies of the line-item veto in US state government have not found any consistent effect on the executive's ability to advance its agenda.[28] Amendatory vetoes give greater power to the executive than deletional vetoes, because they give the executive the power to move policy closer to its own preferred state than would otherwise be possible.[29] But even a suspensory package veto that can be overridden by a simple majority can be effective in stopping or modifying legislation. For example, in Estonia in 1993, president Lennart Meri was able to successfully obtain amendments to the proposed Law on Aliens after issuing a suspensory veto of the bill and proposing amendments based on expert opinions on European law.[26]

Worldwide

Globally, the executive veto over legislation is characteristic of

International bodies

USSR in 1946, after its amendments to a resolution regarding the withdrawal of British troops from Lebanon and Syria were rejected.[32]

USSR in 1946, after its amendments to a resolution regarding the withdrawal of British troops from Lebanon and Syria were rejected.[32]

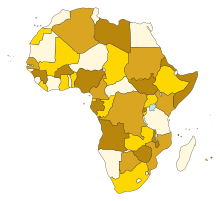

Africa

President Yayi did not take action on a bill that would set an end date to the "exceptional measures" by which he had kept the National Assembly in session. After pocket-vetoing the bill in this way, the president petitioned the Court for constitutional review.[41] The Court ruled that once the deadline for presidential action had passed, only the National Assembly could petition for review, which it did (and prevailed).[41]

President Yayi did not take action on a bill that would set an end date to the "exceptional measures" by which he had kept the National Assembly in session. After pocket-vetoing the bill in this way, the president petitioned the Court for constitutional review.[41] The Court ruled that once the deadline for presidential action had passed, only the National Assembly could petition for review, which it did (and prevailed).[41] absolute majority to become law.[42]

absolute majority to become law.[42] Liberia: The president has package, line item and pocket veto powers under Article 35 of the 1986 Constitution. The President has twenty days to sign a bill into law, but may veto either the entire bill or parts of it, after which the Legislature must re-pass it with a two-thirds majority of both houses. If the President does not sign a bill within twenty days and the Legislature adjourns, the bill fails.[44]

Liberia: The president has package, line item and pocket veto powers under Article 35 of the 1986 Constitution. The President has twenty days to sign a bill into law, but may veto either the entire bill or parts of it, after which the Legislature must re-pass it with a two-thirds majority of both houses. If the President does not sign a bill within twenty days and the Legislature adjourns, the bill fails.[44] South Africa: The president has a weak constitutional veto.[45] The president can return a bill to the National Assembly if the president has reservations about the bill's constitutionality.[46] If the National Assembly passes the bill a second time, the president must either sign it or refer it to the Constitutional Court of South Africa for a final decision on whether the bill is constitutional.[46] If there are no constitutional concerns, the president's assent to legislation is mandatory.

South Africa: The president has a weak constitutional veto.[45] The president can return a bill to the National Assembly if the president has reservations about the bill's constitutionality.[46] If the National Assembly passes the bill a second time, the president must either sign it or refer it to the Constitutional Court of South Africa for a final decision on whether the bill is constitutional.[46] If there are no constitutional concerns, the president's assent to legislation is mandatory. Uganda: The president has package veto and item veto powers.[47] This power must be exercised within 30 days of receiving the legislation.[47] The first time the president returns a bill to the Parliament, the Parliament can pass it again by a simple majority vote. If the president returns it a second time, the Parliament can override the veto with a two-thirds vote.[47] This occurred for example in the passage of the Income Tax Amendment Act 2016, which exempted legislators' allowances from taxation.[48][49]

Uganda: The president has package veto and item veto powers.[47] This power must be exercised within 30 days of receiving the legislation.[47] The first time the president returns a bill to the Parliament, the Parliament can pass it again by a simple majority vote. If the president returns it a second time, the Parliament can override the veto with a two-thirds vote.[47] This occurred for example in the passage of the Income Tax Amendment Act 2016, which exempted legislators' allowances from taxation.[48][49] Zambia: Under the 1996 constitution, the president had an absolute pocket veto: if he neither assented to legislation nor returned it to parliament for a potential override, it was permanently dead.[50] This unusual power was eliminated in a general reorganization of the Constitution's legislative provisions in 2016.[51][52]

Zambia: Under the 1996 constitution, the president had an absolute pocket veto: if he neither assented to legislation nor returned it to parliament for a potential override, it was permanently dead.[50] This unusual power was eliminated in a general reorganization of the Constitution's legislative provisions in 2016.[51][52]

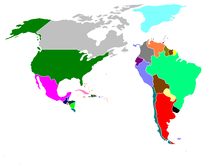

Americas

Government of Brazil

Government of Brazil