Arcturus

| Observation data Epoch J2000 Equinox J2000 | |

|---|---|

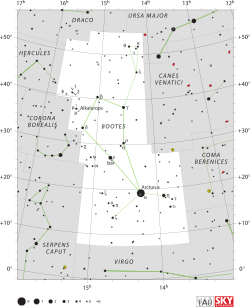

| Constellation | Boötes |

Pronunciation

|

/ɑːrkˈtjʊərəs/ |

| Right ascension | 14h 15m 39.7s[1] |

| Declination | +19° 10′ 56″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | −0.05[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | K1.5 III Fe−0.5[3] |

| Apparent magnitude (J) | −2.25[2] |

| U−B color index | +1.28[2] |

| B−V color index | +1.23[2] |

| R−I color index | +0.65[2] |

| Note (category: variability): | H and K emission vary. |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | −0.30±0.02[6] |

| Details | |

Gyr | |

GCTP 3242.00 | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

| Data sources: | |

Arcturus is the brightest

Located relatively close at 36.7 light-years from the Sun, Arcturus is a red giant of spectral type K1.5III—an aging star around 7.1 billion years old that has used up its core hydrogen and evolved off the main sequence. It is about the same mass as the Sun, but has expanded to 25 times its size and is around 170 times as luminous. Its diameter is 35 million kilometres.

Nomenclature

The traditional name Arcturus is Latinised from the ancient Greek Ἀρκτοῦρος (Arktouros) and means "Guardian of the Bear",[9] ultimately from ἄρκτος (arktos), "bear"[10] and οὖρος (ouros), "watcher, guardian".[11]

The designation of Arcturus as α Boötis (Latinised to Alpha Boötis) was made by Johann Bayer in 1603. In 2016, the International Astronomical Union organized a Working Group on Star Names (WGSN) to catalog and standardize proper names for stars. The WGSN's first bulletin of July 2016 included a table of the first two batches of names approved by the WGSN, which included Arcturus for α Boötis.[12][13]

Observation

With an

Arcturus is visible from both of

Ptolemy described Arcturus as subrufa ("slightly red"): it has a B-V color index of +1.23, roughly midway between Pollux (B-V +1.00) and Aldebaran (B-V +1.54).[15]

Physical characteristics

Based upon an annual

Arcturus is moving rapidly (122 km/s or 270,000 mph) relative to the Sun, and is now almost at its closest point to the Sun. Closest approach will happen in about 4,000 years, when the star will be a few hundredths of a light-year closer to Earth than it is today. (In antiquity, Arcturus was closer to the centre of the constellation.

With an absolute magnitude of −0.30, Arcturus is, together with Vega and Sirius, one of the most luminous stars in the Sun's neighborhood. It is about 110 times brighter than the Sun in visible light wavelengths, but this underestimates its strength as much of the light it gives off is in the infrared; total (bolometric) power output is about 180 times that of the Sun. With a near-infrared J band magnitude of −2.2, only Betelgeuse (−2.9) and R Doradus (−2.6) are brighter. The lower output in visible light is due to a lower efficacy as the star has a lower surface temperature than the Sun.

There have been suggestions that Arcturus might be a member of a binary system with a faint, cool companion, but no companion has been directly detected.[7] In the absence of a binary companion, the mass of Arcturus cannot be measured directly, but models suggest it is slightly greater than that of the Sun. Evolutionary matching to the observed physical parameters gives a mass of 1.08±0.06 M☉,[7] while the oxygen isotope ratio for a first dredge-up star gives a mass of 1.2 M☉.[21] Given the star's evolutionary state, it is expected to have undergone significant mass loss in the past.[22] The star displays magnetic activity that is heating the coronal structures, and it undergoes a solar-type magnetic cycle with a duration that is probably less than 14 years. A weak magnetic field has been detected in the photosphere with a strength of around half a gauss. The magnetic activity appears to lie along four latitudes and is rotationally modulated.[23]

Arcturus is estimated to be around 6 to 8.5 billion years old,[7] but there is some uncertainty about its evolutionary status.[24] Based upon the color characteristics of Arcturus, it is currently ascending the red-giant branch and will continue to do so until it accumulates a large enough degenerate helium core to ignite the helium flash.[7] It has likely exhausted the hydrogen from its core and is now in its active hydrogen shell burning phase. However, Charbonnel et al. (1998) placed it slightly above the horizontal branch, and suggested it has already completed the helium flash stage.[24]

Spectrum

Arcturus has

The spectrum shows a dramatic transition from

Astronomers term "metals" those elements with higher

Oscillations

As one of the brightest stars in the sky, Arcturus has been the subject of a number of studies in the emerging field of

Asteroseismological measurements allow direct calculation of the mass and radius, giving values of 0.8±0.2 M☉ and 27.9±3.4 R☉. This form of modelling is still relatively inaccurate, but a useful check on other models.[31]

Possible planetary system

Hipparcos satellite astrometry suggested that Arcturus is a binary star, with the companion about twenty times dimmer than the primary and orbiting close enough to be at the very limits of humans' current ability to make it out. Recent results remain inconclusive, but do support the marginal Hipparcos detection of a binary companion.[32]

In 1993, radial velocity measurements of Aldebaran, Arcturus and Pollux showed that Arcturus exhibited a long-period radial velocity oscillation, which could be interpreted as a substellar companion. This

Mythology

One astronomical tradition associates Arcturus with the mythology around

Aratus in his Phaenomena said that the star Arcturus lay below the belt of Arctophylax, and according to Ptolemy in the Almagest it lay between his thighs.[35]

An alternative lore associates the name with the legend around Icarius, who gave the gift of wine to other men, but was murdered by them, because they had had no experience with intoxication and mistook the wine for poison. It is stated this Icarius, became Arcturus, while his dog, Maira, became Canicula (Procyon), although "Arcturus" here may be used in the sense of the constellation rather than the star.[36]

Cultural significance

As one of the brightest stars in the sky, Arcturus has been significant to observers since antiquity.

In ancient Mesopotamia, it was linked to the god Enlil, and also known as Shudun, "yoke",[19] or SHU-PA of unknown derivation in the Three Stars Each Babylonian star catalogues and later MUL.APIN around 1100 BC.[37]

In ancient Greek the star is found in ancient astronomical literature, e.g. Hesiod's Work and Days, circa 700 BC,[19] as well as Hipparchus's and Ptolemy's star catalogs. The folk-etymology connecting the star name with the bears (Greek: ἄρκτος, arktos) was probably invented much later.[citation needed] It fell out of use in favour of Arabic names until it was revived in the Renaissance.[38]

In Arabic, Arcturus is one of two stars called al-simāk "the uplifted ones" (the other is Spica). Arcturus is specified as السماك الرامح as-simāk ar-rāmiħ "the uplifted one of the lancer". The term Al Simak Al Ramih has appeared in Al Achsasi Al Mouakket catalogue (translated into Latin as Al Simak Lanceator).[39] This has been variously romanized in the past, leading to obsolete variants such as Aramec and Azimech. For example, the name Alramih is used in Geoffrey Chaucer's A Treatise on the Astrolabe (1391). Another Arabic name is Haris-el-sema, from حارس السماء ħāris al-samā’ "the keeper of heaven".[40][41][42] or حارس الشمال ħāris al-shamāl’ "the keeper of north".[43]

In Indian astronomy, Arcturus is called Swati or Svati (Devanagari स्वाति, Transliteration IAST svāti, svātī́), possibly 'su' + 'ati' ("great goer", in reference to its remoteness) meaning very beneficent. It has been referred to as "the real pearl" in Bhartṛhari's kāvyas.[44]

In

The

Prehistoric Polynesian navigators knew Arcturus as Hōkūleʻa, the "Star of Joy". Arcturus is the zenith star of the Hawaiian Islands. Using Hōkūleʻa and other stars, the Polynesians launched their double-hulled canoes from Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands. Traveling east and north they eventually crossed the equator and reached the latitude at which Arcturus would appear directly overhead in the summer night sky. Knowing they had arrived at the exact latitude of the island chain, they sailed due west on the trade winds to landfall. If Hōkūleʻa could be kept directly overhead, they landed on the southeastern shores of the Big Island of Hawaii. For a return trip to Tahiti the navigators could use Sirius, the zenith star of that island. Since 1976, the Polynesian Voyaging Society's Hōkūleʻa has crossed the Pacific Ocean many times under navigators who have incorporated this wayfinding technique in their non-instrument navigation.

Arcturus had several other names that described its significance to indigenous Polynesians. In the Society Islands, Arcturus, called Ana-tahua-taata-metua-te-tupu-mavae ("a pillar to stand by"), was one of the ten "pillars of the sky", bright stars that represented the ten heavens of the Tahitian afterlife.[48] In Hawaii, the pattern of Boötes was called Hoku-iwa, meaning "stars of the frigatebird". This constellation marked the path for Hawaiʻiloa on his return to Hawaii from the South Pacific Ocean.[49] The Hawaiians called Arcturus Hoku-leʻa.[50] It was equated to the Tuamotuan constellation Te Kiva, meaning "frigatebird", which could either represent the figure of Boötes or just Arcturus.[51] However, Arcturus may instead be the Tuamotuan star called Turu.[52] The Hawaiian name for Arcturus as a single star was likely Hoku-leʻa, which means "star of gladness", or "clear star".[53] In the Marquesas Islands, Arcturus was probably called Tau-tou and was the star that ruled the month approximating January. The Māori and Moriori called it Tautoru, a variant of the Marquesan name and a name shared with Orion's Belt.[54]

In Inuit astronomy, Arcturus is called the Old Man (Uttuqalualuk in Inuit languages) and The First Ones (Sivulliik in Inuit languages).[55]

The

Early-20th-century Armenian scientist

In popular culture

In Ancient Rome, the star's celestial activity was supposed to portend tempestuous weather, and a personification of the star acts as narrator of the prologue to Plautus' comedy Rudens (circa 211 BC).[58][59]

The Kāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra, compiled at the end of the 4th century or beginning of the 5th century, names one of Avalokiteśvara's meditative absorptions as "The face of Arcturus".[60]

One of the possible etymologies offered for the name "Arthur" assumes that it is derived from "Arcturus" and that the late 5th to early 6th-century figure on whom the myth of King Arthur is based was originally named for the star.[59][61][62][63][64][65]

In the

Arcturus's light was employed in the mechanism used to open the 1933 Chicago World's Fair. The star was chosen as it was thought that light from Arcturus had started its journey at about the time of the previous Chicago World's Fair in 1893 (at 36.7 light-years away, the light actually started in 1896).[67]

At the height of the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln observed Arcturus through a 9.6-inch refractor telescope when he visited the Naval Observatory in Washington, DC, in August, 1863.[68]

References

- ^ S2CID 18759600.

- ^ Bibcode:2002yCat.2237....0D.

- ^ doi:10.1086/191373.

- .

- ^ a b Perryman; et al. (1997). "HIP 69673". The Hipparcos and Tycho Catalogues.

- ^ S2CID 2756572.

- ^ S2CID 119186472.

- S2CID 55901104.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "Ἀρκτοῦρος". A Greek-English Lexicon. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "ἄρκτος". A Greek-English Lexicon. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "οὖρος". A Greek-English Lexicon. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

- ^ "Bulletin of the IAU Working Group on Star Names, No. 1" (PDF). Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ "IAU Catalog of Star Names". Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-387-95436-3.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-471-70410-2.

- ^ Schaaf, p. 257.

- ^ Rao, Joe (June 15, 2007). "Arc to Arcturus, Speed on to Spica". Space.com. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ^ "Follow the arc to Arcturus, and drive a spike to Spica | EarthSky.org". earthsky.org. April 8, 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ^ Bibcode:1998JBAA..108...79R.

- S2CID 119253279.

- S2CID 56386673.

- S2CID 53652388. A141.

- . A100.

- ^ S2CID 119268407.

- S2CID 119417105.

- Bibcode:1968pmas.book.....G.

- ^ Bibcode:2005ASPC..336..321H.

- S2CID 6408779.

- S2CID 119095123. A23.

- S2CID 120697563.

- S2CID 15061735.

- S2CID 14176311., and see references therein.

- doi:10.1086/173002.

- ISBN 9780198716983.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian. "Star Tales Boötes". Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ Eratosthenes et al. (2015), pp. 38–40, p. 182 (note to p. 40)

- Bibcode:1998JBAA..108....9R.

- ISBN 978-1-931559-44-7.

- .

- ^ "List of the 25 brightest stars". Jordanian Astronomical Society. Archived from the original on March 16, 2012. Retrieved March 28, 2007.

- ^ Allen, Richard Hinckley (1936). Star-names and their meanings. pp. 100–101.

- ^ Wehr, Hans (1994). Cowan, J. Milton (ed.). A dictionary of modern written Arabic.

- Bibcode:1944PA.....52....8D.

- ISBN 978-0-8021-4877-3.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85538-306-7.

- S2CID 118454721.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-86451-356-1.

- Bibcode:1941msra.book.....M.

- ^ Makemson 1941, p. 209.

- ^ Makemson 1941, p. 280.

- ^ Makemson 1941, p. 221.

- ^ Makemson 1941, p. 264.

- ^ Makemson 1941, p. 210.

- ^ Makemson 1941, p. 260.

- ^ "Arcturus". Constellation Guide. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- JSTOR 533799.

- ^ Daghavarian, Nazaret (1903). Ancient Armenian Religions (in Armenian) (PDF). p. 19. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ Plautus. "Rudens". p. prol. 71.

- ^ a b Lewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles (1879). "arctūrus". A Latin Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Available on the Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Alan Roberts, Peter; Yeshi, Tulku (2013). "Karandavyuha Sutra Page 45" (PDF). Pacificbuddha. 84000.

- ISBN 978-3825351076.

- ^ Zimmer, Stefan (March 2009). "The Name of Arthur – A New Etymology". Journal of Celtic Linguistics. 13 (1). University of Wales Press: 131–136.

- ISBN 978-8886495806.

- ISBN 978-0761822189.

- ^ Chambers, Edmund Kerchever (1964). Arthur of Britain. Speculum Historiale. p. 170.

- ISBN 978-0-87542-832-1.

- ^ "The opening ceremony of A Century of Progress". Century of Progress World's Fair, 1933-1934. University of Illinois-Chicago. January 2008. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ^ Talcott, Rich (July 14, 2014). "Lincoln and the cosmos". Astronomy Magazine. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

Further reading

- Harper, Graham M.; et al. (June 2022), "The Wind Temperature and Mass-loss Rate of Arcturus (K1.5 III)", The Astrophysical Journal, 932 (1): 57, S2CID 249880096, 57.

- Isidoro-García, L.; et al. (January 2022), "Theoretical lifetimes and Stark broadening parameters for visible-infrared spectral lines of V I in Arcturus", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 509 (3): 4538–4554, .

- Kushniruk, Iryna; Bensby, Thomas (November 2019), "Disentangling the Arcturus stream", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 631: A47, S2CID 202558933, A47.

- Wood, M. P.; et al. (February 2018), "Vanadium Transitions in the Spectrum of Arcturus", The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 234 (2): 25, S2CID 119356096, 25.

- Küker, M.; Rüdiger, G. (January 2011), "Differential rotation and meridional flow of Arcturus", Astronomische Nachrichten, 332 (1): 83, .

- Lacour, S.; et al. (July 2008), "The limb-darkened Arcturus: imaging with the IOTA/IONIC interferometer", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 485 (2): 561–570, S2CID 18853087.

- Brown, Kevin I. T.; et al. (June 2008), "Long-Term Spectroscopic Monitoring of Arcturus", The Astrophysical Journal, 679 (2): 1531–1540, S2CID 121170557.

- Tarrant, N. J.; et al. (November 2007), "Asteroseismology of red giants: photometric observations of Arcturus by SMEI", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters, 382 (1): L48–L52, S2CID 5666311.

- Brown, Kevin I. T. (February 2007), "Long-Term Spectroscopic and Precise Radial Velocity Monitoring of Arcturus", The Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 119 (852): 237, S2CID 121637958.

- Gray, David F.; Brown, Kevin I. T. (August 2006), "The Rotation of Arcturus and Active Longitudes on Giant Stars", The Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 118 (846): 1112–1118, S2CID 120918694.

- Cohen, Martin; et al. (June 2005), "Far-Infrared and Millimeter Continuum Studies of K Giants: α Bootis and α Tauri", The Astronomical Journal, 129 (6): 2836–2848, S2CID 119419198.

- Navarro, Julio F.; et al. (January 2004), "The Extragalactic Origin of the Arcturus Group", The Astrophysical Journal, 601 (1): L43–L46, S2CID 10638792.

- Retter, Alon; et al. (July 2003), "Oscillations in Arcturus from WIRE Photometry", The Astrophysical Journal, 591 (2): L151–L154, S2CID 119083930.

- Ryde, N.; et al. (November 2002), "Detection of Water Vapor in the Photosphere of Arcturus", The Astrophysical Journal, 580 (1): 447–458, S2CID 7672420.

- Griffin, R. E. M.; Lynas-Gray, A. E. (June 1999), "The Effective Temperature of Arcturus", The Astronomical Journal, 117 (6): 2998–3006, S2CID 120907426.

- Turner, Nils H.; et al. (May 1999), "Adaptive Optics Observations of Arcturus using the Mount Wilson 100 Inch Telescope", The Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 111 (759): 556–558, S2CID 2441153.

- Griffin, R. F. (October 1998), "Arcturus as a double star", The Observatory, 118: 299–301, Bibcode:1998Obs...118..299G.

- Quirrenbach, A.; et al. (August 1996), "Angular diameter and limb darkening of Arcturus.", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 312: 160–166, Bibcode:1996A&A...312..160Q.

External links