Osteoporosis

| Osteoporosis | |

|---|---|

exercise, fall prevention, stopping smoking[3] | |

| Medication | Bisphosphonates[5][6] |

| Frequency | 15% (50 year olds), 70% (over 80 year olds)[7] |

Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disorder characterized by low

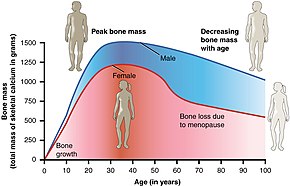

Osteoporosis may be due to lower-than-normal

Prevention of osteoporosis includes a proper diet during childhood, hormone replacement therapy for menopausal women, and efforts to avoid medications that increase the rate of bone loss. Efforts to prevent broken bones in those with osteoporosis include a good diet, exercise, and fall prevention. Lifestyle changes such as stopping smoking and not drinking alcohol may help.[3] Bisphosphonate medications are useful to decrease future broken bones in those with previous broken bones due to osteoporosis. In those with osteoporosis but no previous broken bones, they are less effective.[5][6][11] They do not appear to affect the risk of death.[12]

Osteoporosis becomes more common with age. About 15% of

Signs and symptoms

Osteoporosis has

Fractures

Fractures are a common symptom of osteoporosis and can result in disability.

Fractures of the long bones acutely impair mobility and may require surgery. Hip fracture, in particular, usually requires prompt surgery, as serious risks are associated with it, such as deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. There is also an increased risk of mortality associated with hip surgery, with the mean average mortality rate for Europe being 23.3%, for Asia 17.9%, United States 21% and Australia 24.9%.[23]

Fracture risk calculators assess the risk of fracture based upon several criteria, including

The term "established osteoporosis" is used when a

Risk of falls

There is an increased risk of falls associated with aging. These falls can lead to skeletal damage at the wrist, spine, hip, knee, foot, and ankle. Part of the fall risk is because of impaired eyesight due to many causes, (e.g.

Complications

As well as susceptibility to breaks and fractures, osteoporosis can lead to other complications. Bone fractures from osteoporosis can lead to disability and an increased risk of death after the injury in elderly people.[29] Osteoporosis can decrease the quality of life, increase disabilities, and increase the financial costs to health care systems.[30]

Risk factors

The risk of having osteoporosis includes age and sex. Risk factors include both nonmodifiable (for example, age and some medications that may be necessary to treat a different condition) and modifiable (for example, alcohol use, smoking, vitamin deficiency). In addition, osteoporosis is a recognized complication of specific diseases and disorders. Medication use is theoretically modifiable, although in many cases, the use of medication that increases osteoporosis risk may be unavoidable. Caffeine is not a risk factor for osteoporosis.[31]

Nonmodifiable

- The most important risk factors for osteoporosis are advanced age (in both men and women) and female sex; estrogen deficiency following menopause or surgical removal of the ovaries is correlated with a rapid reduction in bone mineral density, while in men, a decrease in testosterone levels has a comparable (but less pronounced) effect.[33][34]

- Ethnicity: While osteoporosis occurs in people from all ethnic groups,

- Heredity: Those with a family history of fracture or osteoporosis are at an increased risk; the heritability of the fracture, as well as low bone mineral density, is relatively high, ranging from 25 to 80%. At least 30 genes are associated with the development of osteoporosis.[36]

- Those who have already had a fracture are at least twice as likely to have another fracture compared to someone of the same age and sex.[37]

- Build: A small stature is also a nonmodifiable risk factor associated with the development of osteoporosis.[38]

Potentially modifiable

- Alcohol: Alcohol intake greater than three units/day) may increase the risk of osteoporosis and people who consumed 0.5-1 drinks a day may have 1.38 times the risk compared to people who do not consume alcohol.[39][40]

- 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol levels and bone mineral density, while PTH is negatively associated with bone mineral density.[4]

- Tobacco smoking: Many studies have associated smoking with decreased bone health, but the mechanisms are unclear.[43][44][45] Tobacco smoking has been proposed to inhibit the activity of osteoblasts, and is an independent risk factor for osteoporosis.[39][46] Smoking also results in increased breakdown of exogenous estrogen, lower body weight and earlier menopause, all of which contribute to lower bone mineral density.[4]

- Malnutrition: Nutrition has an important and complex role in maintenance of good bone. Identified risk factors include low dietary calcium and/or phosphorus, magnesium, zinc, boron, iron, fluoride, copper, vitamins A, K, E and C (and D where skin exposure to sunlight provides an inadequate supply). Excess sodium is a risk factor. High blood acidity may be diet-related, and is a known antagonist of bone.[47] Imbalance of omega-6 to omega-3 polyunsaturated fats is yet another identified risk factor.[48]

- A 2017 meta-analysis of published medical studies shows that higher protein diet helps slightly with lower spine density but does not show significant improvement with other bones.[49] A 2023 meta-analysis sees no evidence for the relation between protein intake and bone health.[50]

- Endurance training: In female endurance athletes, large volumes of training can lead to decreased bone density and an increased risk of osteoporosis.

- Heavy metals: A strong association between cadmium and lead with bone disease has been established. Low-level exposure to cadmium is associated with an increased loss of bone mineral density readily in both genders, leading to pain and increased risk of fractures, especially in the elderly and in females. Higher cadmium exposure results in osteomalacia (softening of the bone).[58]

- Soft drinks: Some studies indicate

Medical disorders

Many diseases and disorders have been associated with osteoporosis.[62] For some, the underlying mechanism influencing the bone metabolism is straightforward, whereas for others the causes are multiple or unknown.

- In general, space flight or in people who are bedridden or use wheelchairs for various reasons.[citation needed]

- testes).

- Endocrine disorders that can induce bone loss include

- Malnutrition, bulimia can also develop osteoporosis. Those with an otherwise adequate calcium intake can develop osteoporosis due to the inability to absorb calcium and/or vitamin D. Other micronutrients such as vitamin K or vitamin B12 deficiencymay also contribute.

- People with rheumatologic disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus and polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis are at increased risk of osteoporosis, either as part of their disease or because of other risk factors (notably corticosteroid therapy). Systemic diseases such as amyloidosis and sarcoidosiscan also lead to osteoporosis.

- Chronic kidney disease can lead to renal osteodystrophy.[68]

- Hematologic disorders linked to osteoporosis are sickle-cell disease and thalassemia.

- Several inherited or genetic disorders have been linked to osteoporosis. These include hemochromatosis,[4] hypophosphatasia[71] (for which it is often misdiagnosed),[72] glycogen storage diseases, homocystinuria,[63] Ehlers–Danlos syndrome,[63] porphyria, Menkes' syndrome, epidermolysis bullosa and Gaucher's disease.

- People with of unknown cause also have a higher risk of osteoporosis. Bone loss can be a feature of complex regional pain syndrome. It is also more frequent in people with Parkinson's disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

- People with iron metabolism) causing a stiffening of the skeleton and kyphosis.

Medication

Certain medications have been associated with an increase in osteoporosis risk; only glucocorticosteroids and anticonvulsants are classically associated, but evidence is emerging with regard to other drugs.

- Steroid-induced osteoporosis (SIOP) arises due to use of glucocorticoids – analogous to Cushing's syndrome and involving mainly the axial skeleton. The synthetic glucocorticoid prescription drug prednisone is a main candidate after prolonged intake. Some professional guidelines recommend prophylaxis in patients who take the equivalent of more than 30 mg hydrocortisone (7.5 mg of prednisolone), especially when this is in excess of three months.[75] It is recommended to use calcium or Vitamin D as prevention.[76] Alternate day use may not prevent this complication.[77]

- antiepileptics – these probably accelerate the metabolism of vitamin D.[78]

- L-Thyroxine over-replacement may contribute to osteoporosis, in a similar fashion as thyrotoxicosis does.[62]This can be relevant in subclinical hypothyroidism.

- Several drugs induce hypogonadism, for example depot progesterone and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists.

- Anticoagulants – long-term use of heparin is associated with a decrease in bone density,[79] and warfarin (and related coumarins) have been linked with an increased risk in osteoporotic fracture in long-term use.[80]

- antacids.[62]

- Thiazolidinediones (used for diabetes) – rosiglitazone and possibly pioglitazone, inhibitors of PPARγ, have been linked with an increased risk of osteoporosis and fracture.[82]

- Chronic lithium therapy has been associated with osteoporosis.[62]

Evolutionary

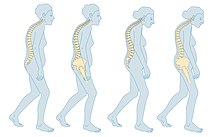

Age-related bone loss is common among humans due to exhibiting less dense bones than other primate species.[83] Because of the more porous bones of humans, frequency of severe osteoporosis and osteoporosis related fractures is higher.[84] The human vulnerability to osteoporosis is an obvious cost but it can be justified by the advantage of bipedalism inferring that this vulnerability is the byproduct of such.[84] It has been suggested that porous bones help to absorb the increased stress that we have on two surfaces compared to our primate counterparts who have four surfaces to disperse the force.[83] In addition, the porosity allows for more flexibility and a lighter skeleton that is easier to support.[84] One other consideration may be that diets today have much lower amounts of calcium than the diets of other primates or the tetrapedal ancestors to humans which may lead to higher likelihood to show signs of osteoporosis.[85]

Fracture risk assessment

In the absence of risk factors other than sex and age a BMD measurement using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is recommended for women at age 65. For women with risk factors a clinical FRAX is advised at age 50.

Pathogenesis

The underlying mechanism in all cases of osteoporosis is an imbalance between

The three main mechanisms by which osteoporosis develops are an inadequate peak bone mass (the skeleton develops insufficient mass and strength during growth), excessive bone resorption, and inadequate formation of new bone during remodeling, likely due to mesenchymal stem cells biasing away from the

The activation of osteoclasts is regulated by various molecular signals, of which

-

Light micrograph of an osteoclast displaying typical distinguishing characteristics: a large cell with multiple nuclei and a "foamy" cytosol.

-

Light micrograph of osteoblasts, several displaying a prominent Golgi apparatus, actively synthesizing osteoid containing two osteocytes.

-

Collapse of vertebra on the right, normal on the left

Diagnosis

Osteoporosis can be diagnosed using conventional radiography and by measuring the

In addition to the detection of abnormal BMD, the diagnosis of osteoporosis requires investigations into potentially modifiable underlying causes; this may be done with

Conventional radiography

Conventional radiography is useful, both by itself and in conjunction with CT or MRI, for detecting complications of osteopenia (reduced bone mass; pre-osteoporosis), such as fractures; for differential diagnosis of osteopenia; or for follow-up examinations in specific clinical settings, such as soft tissue calcifications, secondary hyperparathyroidism, or osteomalacia in renal osteodystrophy. However, radiography is relatively insensitive to detection of early disease and requires a substantial amount of bone loss (about 30%) to be apparent on X-ray images.[95][96]

The main radiographic features of generalized osteoporosis are cortical thinning and increased radiolucency. Frequent complications of osteoporosis are vertebral fractures for which spinal radiography can help considerably in diagnosis and follow-up. Vertebral height measurements can objectively be made using plain-film X-rays by using several methods such as height loss together with area reduction, particularly when looking at vertical deformity in T4-L4, or by determining a spinal fracture index that takes into account the number of vertebrae involved. Involvement of multiple vertebral bodies leads to kyphosis of the thoracic spine, leading to what is known as

Dual-energy X-ray

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA scan) is considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is diagnosed when the bone mineral density is less than or equal to 2.5 standard deviations below that of a young (30–40-year-old[4]:58), healthy adult women reference population. This is translated as a T-score. But because bone density decreases with age, more people become osteoporotic with increasing age.[4]:58 The World Health Organization has established the following diagnostic guidelines:[4][27]

| Category | T-score range | % young women |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | T-score ≥ −1.0 | 85% |

| Osteopenia | −2.5 < T-score < −1.0 | 14% |

| Osteoporosis | T-score ≤ −2.5 | 0.6% |

| Severe osteoporosis | T-score ≤ −2.5 with fragility fracture[27] |

The International Society for Clinical Densitometry takes the position that a diagnosis of osteoporosis in men under 50 years of age should not be made on the basis of densitometric criteria alone. It also states, for premenopausal women, Z-scores (comparison with age group rather than peak bone mass) rather than T-scores should be used, and the diagnosis of osteoporosis in such women also should not be made on the basis of densitometric criteria alone.[99]

Biomarkers

Chemical

| Condition | Calcium | Phosphate | Alkaline phosphatase | Parathyroid hormone | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteopenia | unaffected | unaffected | normal | unaffected | decreased bone mass |

| Osteopetrosis | unaffected | unaffected | elevated | unaffected [citation needed] | thick dense bones also known as marble bone |

| Osteomalacia and rickets | decreased | decreased | elevated | elevated | soft bones |

| Osteitis fibrosa cystica | elevated | decreased | elevated | elevated | brown tumors |

| Paget's disease of bone | unaffected | unaffected | variable (depending on stage of disease) | unaffected | abnormal bone architecture |

Other measuring tools

Quantitative computed tomography (QCT) differs from DXA in that it gives separate estimates of BMD for trabecular and cortical bone and reports precise volumetric mineral density in mg/cm3 rather than BMD's relative Z-score. Among QCT's advantages: it can be performed at axial and peripheral sites, can be calculated from existing CT scans without a separate radiation dose, is sensitive to change over time, can analyze a region of any size or shape, excludes irrelevant tissue such as fat, muscle, and air, and does not require knowledge of the patient's subpopulation in order to create a clinical score (e.g. the Z-score of all females of a certain age). Among QCT's disadvantages: it requires a high radiation dose compared to DXA, CT scanners are large and expensive, and because its practice has been less standardized than BMD, its results are more operator-dependent. Peripheral QCT has been introduced to improve upon the limitations of DXA and QCT.[93]

Quantitative ultrasound has many advantages in assessing osteoporosis. The modality is small, no ionizing radiation is involved, measurements can be made quickly and easily, and the cost of the device is low compared with DXA and QCT devices. The calcaneus is the most common skeletal site for quantitative ultrasound assessment because it has a high percentage of trabecular bone that is replaced more often than cortical bone, providing early evidence of metabolic change. Also, the calcaneus is fairly flat and parallel, reducing repositioning errors. The method can be applied to children, neonates, and preterm infants, just as well as to adults.[93] Some ultrasound devices can be used on the tibia.[102]

Screening

The

In men the harm versus benefit of screening for osteoporosis is unknown.[103] Prescrire states that the need to test for osteoporosis in those who have not had a previous bone fracture is unclear.[105] The International Society for Clinical Densitometry suggest BMD testing for men 70 or older, or those who are indicated for risk equal to that of a 70‑year‑old.[106] A number of tools exist to help determine who is reasonable to test.[107]

Prevention

Lifestyle prevention of osteoporosis is in many aspects the inverse of the potentially modifiable risk factors.[108] As tobacco smoking and high alcohol intake have been linked with osteoporosis, smoking cessation and moderation of alcohol intake are commonly recommended as ways to help prevent it.[109]

In people with coeliac disease adherence to a gluten-free diet decreases the risk of developing osteoporosis[110] and increases bone density.[65] The diet must ensure optimal calcium intake (of at least one gram daily) and measuring vitamin D levels is recommended, and to take specific supplements if necessary.[110]

Nutrition

Studies of the benefits of supplementation with calcium and vitamin D are conflicting, possibly because most studies did not have people with low dietary intakes. is associated with calcium supplementation.

Vitamin K deficiency is also a risk factor for osteoporotic fractures.[119] The gene gamma-glutamyl carboxylase (GGCX) is dependent on vitamin K. Functional polymorphisms in the gene could attribute to variation in bone metabolism and BMD.[120] Vitamin K2 is also used as a means of treatment for osteoporosis and the polymorphisms of GGCX could explain the individual variation in the response to treatment of vitamin K.[121]

Dietary sources of calcium include dairy products, leafy greens, legumes, and beans.[122] There has been conflicting evidence about whether or not dairy is an adequate source of calcium to prevent fractures. The National Academy of Sciences recommends 1,000 mg of calcium for those aged 19–50, and 1,200 mg for those aged 50 and above.[123] A review of the evidence shows no adverse effect of higher protein intake on bone health.[124]

Physical exercise

There is limited evidence indicating that exercise is helpful in promoting bone health.[125] There is some evidence that physical exercise may be beneficial for bone density in postmenopausal women and lead to a slightly reduced risk of a bone fracture (absolute difference 4%).[126] Weight bearing exercise has been found to cause an adaptive response in the skeleton.[127] Weight bearing exercise promotes osteoblast activity, protecting bone density.[128] A position statement concluded that increased bone activity and weight-bearing exercises at a young age prevent bone fragility in adults.[129] Bicycling and swimming are not considered weight-bearing exercise. Neither contribute to slowing bone loss with age, and professional bicycle racing has a negative effect on bone density.[130]

Low-quality evidence suggests that exercise may reduce pain and improve quality of life of people with vertebral fractures and there is moderate-quality evidence that exercise will likely improve physical performance in individuals with vertebral fractures.[131]

Physical therapy

People with osteoporosis are at higher risk of falls due to poor postural control, muscle weakness, and overall deconditioning.[132] Postural control is important to maintaining functional movements such as walking and standing. Physical therapy may be an effective way to address postural weakness that may result from vertebral fractures, which are common in people with osteoporosis. Physical therapy treatment plans for people with vertebral fractures include balance training, postural correction, trunk and lower extremity muscle strengthening exercises, and moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity.[131] The goal of these interventions are to regain normal spine curvatures, increase spine stability, and improve functional performance.[131] Physical therapy interventions were also designed to slow the rate of bone loss through home exercise programs.[132]

Physical therapy can aid in overall prevention in the development of osteoporosis through therapeutic exercise. Prescribed amounts of mechanical loading or increased forces on the bones promote bone formation and vascularization in various ways, therefore offering a preventative measure that is not reliant on drugs. Specific exercise interacts with the body's hormones and signaling pathways which encourages the maintenance of a healthy skeleton.[135]

Hormone therapy

Reduced

Management

Lifestyle

Weight-bearing endurance exercise and/or exercises to strengthen muscles improve bone strength in those with osteoporosis.

Pharmacologic therapy

The US National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends pharmacologic treatment for patients with hip or spine fracture thought to be related to osteoporosis, those with BMD 2.5 SD or more below the young normal mean (T-score -2.5 or below), and those with BMD between 1 and 2.5 SD below normal mean whose 10-year risk, using FRAX, for hip fracture is equal or more than 3%.[139] Bisphosphonates are useful in decreasing the risk of future fractures in those who have already sustained a fracture due to osteoporosis.[5][6][109][140] This benefit is present when taken for three to four years.[141][142] They do not appear to change the overall risk of death.[12] Tentative evidence does not support the use of bisphosphonates as a standard treatment for secondary osteoporosis in children.[142] Different bisphosphonates have not been directly compared, therefore it is unknown if one is better than another.[109] Fracture risk reduction is between 25 and 70% depending on the bone involved.[109] There are concerns of atypical femoral fractures and osteonecrosis of the jaw with long-term use, but these risks are low.[109][143] With evidence of little benefit when used for more than three to five years and in light of the potential adverse events, it may be appropriate to stop treatment after this time.[141] One medical organization recommends that after five years of medications by mouth or three years of intravenous medication among those at low risk, bisphosphonate treatment can be stopped.[144][145] In those at higher risk they recommend up to ten years of medication by mouth or six years of intravenous treatment.[144]

The goal of osteoporosis management is to prevent osteoporotic fractures, but for those who have sustained one already it is more urgent to prevent a secondary fracture.

For those with osteoporosis but who have not had a fracture, evidence does not support a reduction in fracture risk with

Fluoride supplementation does not appear to be effective in postmenopausal osteoporosis, as even though it increases bone density, it does not decrease the risk of fractures.[150][151]

Romosozumab (sold under the brand name Evenity) is a monoclonal antibody against sclerostin. Romosozumab is usually reserved for patients with very high fracture risk and is the only available drug therapy for osteoporosis that leads to simultaneous inhibition of bone resorption together with an anabolic effect.[156][157]

Certain medications like alendronate, etidronate, risedronate, raloxifene, and strontium ranelate can help to prevent osteoporotic fragility fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis.[158] Tentative evidence suggests that Chinese herbal medicines may have potential benefits on bone mineral density.[159]

Prognosis

| WHO category | Age 50–64 | Age > 64 | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 5.3 | 9.4 | 6.6 |

| Osteopenia | 11.4 | 19.6 | 15.7 |

| Osteoporosis | 22.4 | 46.6 | 40.6 |

Although people with osteoporosis have increased mortality due to the complications of fracture, the fracture itself is rarely lethal.

Hip fractures can lead to decreased mobility and additional risks of numerous complications (such as

Vertebral fractures, while having a smaller impact on mortality, can lead to severe chronic pain of neurogenic origin, which can be hard to control, as well as deformity. Though rare, multiple vertebral fractures can lead to such severe hunchback (kyphosis), the resulting pressure on internal organs can impair one's ability to breathe.

Apart from risk of death and other complications, osteoporotic fractures are associated with a reduced health-related quality of life.[162]

The condition is responsible for millions of fractures annually, mostly involving the lumbar vertebrae, hip, and wrist. Fragility fractures of ribs are also common in men.

Fractures

Hip fractures are responsible for the most serious consequences of osteoporosis. In the United States, more than 250,000 hip fractures annually are attributable to osteoporosis.[163] A 50-year-old white woman is estimated to have a 17.5% lifetime risk of fracture of the proximal femur. The incidence of hip fractures increases each decade from the sixth through the ninth for both women and men for all populations. The highest incidence is found among men and women ages 80 or older.[164]

Between 35 and 50% of all women over 50 had at least one

In the United States, 250,000 wrist fractures annually are attributable to osteoporosis.[163] Wrist fractures are the third most common type of osteoporotic fractures. The lifetime risk of sustaining a Colles' fracture is about 16% for white women. By the time women reach age 70, about 20% have had at least one wrist fracture.[164]

Epidemiology

This article needs to be updated. (December 2020) |

It is estimated that 200 million people have osteoporosis.

Postmenopausal women have a higher rate of osteoporosis and fractures than older men.[168] Postmenopausal women have decreased estrogen which contributes to their higher rates of osteoporosis.[168] A 60-year-old woman has a 44% risk of fracture while a 60-year-old man has a 25% risk of fracture.[168]

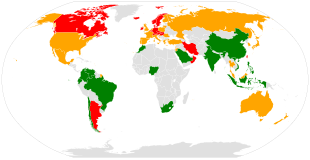

There are 8.9 million fractures worldwide per year due to osteoporosis.[169] Globally, 1 in 3 women and 1 in 5 men over the age of 50 will have an osteoporotic fracture.[169] Data from the United States shows a decrease in osteoporosis within the general population and in white women, from 18% in 1994 to 10% in 2006.[170] White and Asian people are at greater risk.[3] People of African descent are at a decreased risk of fractures due to osteoporosis, although they have the highest risk of death following an osteoporotic fracture.[170]

It has been shown that latitude affects risk of osteoporotic fracture.[166] Areas of higher latitude such as Northern Europe receive less Vitamin D through sunlight compared to regions closer to the equator, and consequently have higher fracture rates in comparison to lower latitudes.[166] For example, Swedish men and women have a 13% and 28.5% risk of hip fracture by age 50, respectively, whereas this risk is only 1.9% and 2.4% in Chinese men and women.[170] Diet may also be a factor that is responsible for this difference, as vitamin D, calcium, magnesium, and folate are all linked to bone mineral density.[171]

There is also an association between Celiac Disease and increased risk of osteoporosis.[172] In studies with premenopausal females and males, there was a correlation between Celiac Disease and osteoporosis and osteopenia.[172] Celiac Disease can decrease absorption of nutrients in the small intestine such as calcium, and a gluten-free diet can help people with Celiac Disease to revert to normal absorption in the gut.[173]

About 22 million women and 5.5 million men in the European Union had osteoporosis in 2010.[15] In the United States in 2010 about 8 million women and one to 2 million men had osteoporosis.[13][16] This places a large economic burden on the healthcare system due to costs of treatment, long-term disability, and loss of productivity in the working population. The EU spends 37 billion euros per year in healthcare costs related to osteoporosis, and the US spends an estimated US$19 billion annually for related healthcare costs.[169]

History

The link between age-related reductions in bone density goes back to the early 1800s. French pathologist Jean Lobstein coined the term osteoporosis.[17] The American endocrinologist Fuller Albright linked osteoporosis with the postmenopausal state.[174]

Anthropologists have studied skeletal remains that showed loss of bone density and associated structural changes that were linked to a chronic malnutrition in the agricultural area in which these individuals lived. "It follows that the skeletal deformation may be attributed to their heavy labor in agriculture as well as to their chronic malnutrition", causing the osteoporosis seen when radiographs of the remains were made.[175]

See also

References

- ISBN 978-3-12-539683-8.

- ^ "Osteoporosis". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary.

- ^ NIAMS. August 2014. Archivedfrom the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ )

- ^ PMID 18253985.

- ^ PMID 35502787.

- ^ a b c "Chronic rheumatic conditions". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- PMID 25841602.

- ^ Branch NS (7 April 2017). "Osteoporosis". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- ^ "Clinical Challenges: Managing Osteoporosis in Male Hypogonadism". www.medpagetoday.com. 4 June 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ PMID 18254018.

- ^ PMID 31424486.

- ^ S2CID 19534928.

- ^ PMID 18783745.

- ^ PMID 24113838.

- ^ PMID 25657593.

- ^ ISBN 9781421413181. Archivedfrom the original on 23 July 2014.

- ^ a b "Osteoporosis". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, US National Institutes of Health. 1 December 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- OCLC 990065894.

- from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- S2CID 215620114.

- S2CID 28448924.

- PMID 30918799.

- ^ Susan Ott (October 2009). "Fracture Risk Calculator". Archived from the original on 14 October 2009.

- S2CID 49312906.

- S2CID 54632462.

- ^ PMID 7941614.

- PMID 17200478.

- ^ "Osteoporosis - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- PMID 28293453.

- PMID 18523710.

- ISBN 978-1-938168-13-0. Archivedfrom the original on 10 January 2017.

- S2CID 1637184.

- PMID 21941679.

- PMID 12699289.

- ^ from the original on 24 August 2007.

- PMID 17444431.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7817-6555-8.

- ^ PMID 17170416.

- PMID 18456037.

- PMID 15883457.

- PMID 21876835.

- S2CID 244502249.

- PMID 8363002.

- S2CID 19890259.

- S2CID 1179481. Archived from the original(PDF) on 1 March 2019.

- S2CID 18598975. Archived from the originalon 7 August 2009. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- PMID 15817874.

- PMID 28404575.

- PMID 37126148.

- PMID 8805035.

- PMID 16702302.

- S2CID 5867410.

- S2CID 42115482.

- PMID 8370698.

- S2CID 32005973.

- PMID 10953900.

- S2CID 33697569.

- PMID 17023723.

- PMID 14702469.

- S2CID 13532091.

- ^ a b c d e Simonelli, C, et al. (July 2006). "ICSI Health Care Guideline: Diagnosis and Treatment of Osteoporosis, 5th edition". Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2007. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Kohlmeier L (1998). "Osteoporosis – Risk Factors, Screening, and Treatment". Medscape Portals. Archived from the original on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 11 May 2008.

- ^ PMID 18385499.

- ^ PMID 25971649.

- ^ PMID 19193819. Archived from the originalon 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- PMID 25713787.

- ^ "Chronic Kidney Disease". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- PMID 30208859.

- PMID 34307793.

- from the original on 18 January 2017.

- ^ "Hypophosphatasia Case Studies: Dangers of Misdiagnosis". Hypophosphatasia.com. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- PMID 19346153.

- PMID 19268425.

- ISBN 978-1-86016-173-5. Archived from the original(PDF) on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- PMID 10796394.

- S2CID 26017061.

- S2CID 2953573.

- S2CID 2922860.

- PMID 16432096.

- PMID 17190895.

- S2CID 21577063.

- ^ S2CID 43294733.

- ^ PMID 22028933.

- PMID 2053574.

- ^ . Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ PMID 32040934.

- ^ Frost HM, Thomas CC. Bone Remodeling Dynamics. Springfield, IL: 1963.

- PMID 23731620.

- PMID 26244490.

- PMID 29293000.

- PMID 23136547.

- ^ a b c Guglielmi G, Scalzo G (6 May 2010). "Imaging tools transform diagnosis of osteoporosis". Diagnostic Imaging Europe. 26: 7–11. Archived from the original on 2 June 2010.

- PMID 27346916.

- PMID 11996418.

- S2CID 10799509.

- PMID 6768276.

- PMID 3757369.

- S2CID 32856123. quoted in: "Diagnosis of osteoporosis in men, premenopausal women, and children" Archived 24 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- PMID 15876399.

- ISBN 978-1-85317-412-4.

- ^ "Bindex, a Radiation-Free Device for Osteoporosis Screening, FDA Cleared". Medgadget. 27 May 2016. Archived from the original on 15 June 2016.

- ^ PMID 29946735.

- PMID 21242341.

- ^ "100 most recent Archives 2017 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006 2005 Bone fragility: preventing fractures". Prescrire International. 26 (181): 103–106. April 2017. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD). 2013 ISCD Official Positions – Adult. (2013). at "2013 ISCD Official Positions – Adult – International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD)". Archived from the original on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- S2CID 13641749.

- S2CID 29255357.

- ^ PMID 22338309.

- ^ PMID 24917550.

- PMID 25247344.

- ^ S2CID 205090176.

- ^ "Final Recommendation Statement Vitamin D, Calcium, or Combined Supplementation for the Primary Prevention of Fractures in Community-Dwelling Adults: Preventive Medication". www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org. USPSTF Program Office.

- PMID 26420387.

- PMID 20068257.

- ^ PMID 24729336.

- PMID 20671013.

- PMID 21505219.

- PMID 31976057.

- PMID 28125048.

- S2CID 35412918.

- ^ "Preventing and Reversing Osteoporosis". Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ "Dietary Reference Intakes for Adequacy: Calcium and Vitamin D – Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D – NCBI Bookshelf". Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- PMID 28404575.

- PMID 31244903.

- ^ PMID 21735380.

- S2CID 25835205.

- PMID 28612339.

- PMID 26856587.

- PMID 27476628.

- ^ PMID 31273764.

- ^ PMID 29767225.

- ^ PMID 29289937.

- PMID 30142802.

- PMID 31139653.

- PMID 21360219.

- ^ PMID 30324412.

- S2CID 45409462.

- S2CID 4795899.

- ^ S2CID 202564164.

- ^ S2CID 27821662.

- ^ PMID 17943849.

- PMID 23838024.

- ^ PMID 26350171.

- ^ PMID 28492856.

- ^ PMID 31828096..

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - S2CID 229333146.

- ^ Davis S, Sachdeva A, Goeckeritz B, Oliver A (2010). "Approved treatments for osteoporosis and what's in the pipeline". Drug Benefit Trends. 22 (4): 121–124. Archived from the original on 28 July 2010.

- ^ PMID 28304090.

- PMID 11034769.

- S2CID 25890845.

- S2CID 44529401.

- PMID 17054253.

- ^ "Background Document for Meeting of Advisory Committee for Reproductive Health Drugs and Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee" (PDF). FDA. March 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 June 2013.

- ^ "Alendronic acid: medicine to treat and prevent osteoporosis". National Health Service (UK). 24 August 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- S2CID 249200643.

- ^ Office of the Commissioner (24 March 2020). "FDA approves new treatment for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women at high risk of fracture". FDA. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ "Osteoporosis – primary prevention (TA160) : Alendronate, etidronate, risedronate, raloxifene and strontium ranelate for the primary prevention of osteoporotic fragility fractures in postmenopausal women". UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). January 2011. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013.

- PMID 24599707.

- PMID 17846439.

- PMID 11386929.

- S2CID 24283913.

- ^ PMID 8573428.

- ^ a b "MerckMedicus Modules: Osteoporosis – Epidemiology". Merck & Co., Inc. Archived from the original on 28 December 2007. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

- PMID 18165669.

- ^ PMID 22419370.

- ^ International Osteoporosis Foundation. Epidemiology Archived 9 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ PMID 29062981.

- ^ a b c "The Global Burden of Osteoporosis | International Osteoporosis Foundation". www.iofbonehealth.org. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ PMID 21431462.

- S2CID 7641257.

- ^ PMID 30732599.

- ^ "What People With Celiac Disease Need To Know About Osteoporosis | NIH Osteoporosis and Related Bone Diseases National Resource Center". www.bones.nih.gov. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- ^ Albright F, Bloomberg E, Smith PH (1940). "Postmenopausal osteoporosis". Trans. Assoc. Am. Physicians. 55: 298–305.

- .

External links

Media related to Osteoporosis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Osteoporosis at Wikimedia Commons- Handout on Health: Osteoporosis – US National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

- Osteoporosis – l NIH Osteoporosis and Related Bone Diseases – National Resource Center

- PMID 20945569. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- "Osteoporosis". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine.